Original source publication: de Sá-Soares, F. (2010). Interpreting Legislative Controls of DNA Databases. In Karlsson, F., K. Hedström and R.-M. Åhlfeldt (Eds.), Proceedings of the First European Security Conference 2010. Örebro (Sweden).

Interpreting Legislative Controls of DNA Databases

University of Minho, Portugal

Abstract

DNA has been extolled as the fingerprint of modern times. Recognizing its usefulness for identification, several countries have implemented national databases containing DNA profiles to assist criminal investigation and other identification related activities. In order to establish DNA databases, herein perceived as information systems, nation states produce legislative controls to regulate the creation and use of the databases. These controls set the base for subsequent operational procedures and safeguards for the proper use of the databases. Acknowledging the information security requirements of DNA databases, this paper reviews the legislative controls that came into being for the regulation of the Portuguese DNA profiles database. The legal documents were analyzed by applying the theoretical and methodological lens of Theory of Action.

Keywords: DNA Databases; DNA Database Security; Legislative Controls; Legal Controls; Information Security; Theory of Action

1. Introduction

DNA (DeoxyriboNucleic Acid) is a nucleic acid found within the cells of living organisms that contains the genetic code used in the development and functioning of those organisms and that transmits the hereditary pattern [Webster 2002].

DNA was first isolated in 1869 by Miescher [Dahm 2008]. Griffith conducted an experiment in 1928 that suggested DNA carried genetic information [Lorenz and Wackernagel 1994]. In 1937 Astbury showed that DNA had a regular structure [Astbury 1947]. In 1952, Herschey and Chase confirmed DNA’s role in heredity [Hershey and Chase 1952]. One year later, Watson and Crick suggested the first correct double-helix model of DNA structure [Watson and Crick 1953]. Further scientific developments allowed Khorana, Holley and Nirenberg to decipher the genetic code [TNF 1968].

The importance of DNA-related discoveries has spurred interest in using knowledge about DNA in technology, driving new fields of study such as genetic engineering, bioinformatics, and DNA nanotechnology, or extending existing ones, such as forensics.

In the field of forensics, British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys developed the technique of DNA profiling in 1984 [Jeffreys et al. 1985]. By applying this technique, forensic scientists can use biological samples, such as blood, semen, skin, saliva, and hair, to identity a matching DNA of an individual. Usually, DNA profiling is an extremely reliable technique for identification of people by matching DNA profiles. DNA profiling was first used in forensic science to convict Colin Pitchfork in 1988 Enderby murders case [FSS 2008].

From then on, we have witnessed a growing use of DNA profiling, also known as genetic fingerprinting, DNA typing, or DNA testing, in the realm of forensics, with some suggesting DNA constitutes the fingerprint of modern times.

Since the 1990s, several international entities have been advocating the use of DNA analysis in the judicial system and the possibility of creating international accessible databases that include the results of those analyses, the so-called DNA profiles. Several scientific groups, agencies, and police authorities have produced work in the application of DNA profiling in forensics, such as ENFSI (European Network of Forensic Science Institutes), EDNAP (European DNA Profiling Group), NIJ (National Institute of Justice), and INTERPOL.

Worldwide, countries have created DNA forensic databases which are used for criminal investigation purposes. The databases store DNA profiles for matching with DNA profiles obtained from biological samples collected in crime scenes or for purposes of identification of people in other contexts, such as missing persons.

Commonly, these databases may contain three types of information: DNA profiles, personal data, and samples.

Samples are any biological substances which may be utilized for the purpose of DNA analysis. Usually, the origin of samples is human and the samples may be obtained directly from a living person or collected from corpses, things, or places.

DNA profiles are the result of a sample analysis through the examination of DNA markers, defined as specific regions of genome that contain different information in different people and that, according to current scientific knowledge, do not convey health information nor specific hereditary characteristics (what is usually known as non-coding DNA).

Personal data are information related to a singular identified or identifiable individual. In the context of DNA profiling, a set of personal data is associated with a particular person whose DNA profile has been analyzed.

Considering the artifact DNA database, one can usually distinguish two kinds of repositories: DNA profiles databases and biobanks. A DNA profiles database may be understood as a set of structured files containing DNA profiles and personal data. A biobank is any repository of biological samples and their derivatives.

From an information systems perspective, DNA profiles databases and biobanks can be understood as artifacts that contain information of biological nature (the samples) and of symbolic nature (the DNA profiles and the personal data) and that are object of a set of information manipulating activities, namely insertion of information, access to information, comparison of information, and removal of information. By considering these artifacts and their contents, together with the set of manual or computer-based information manipulating activities1 that gives purpose to their use, one is faced with an information system as an object of study.

Taking into account the sensitivity of the information contained in the databases and the purposes that their users have in mind when manipulating the data, we get an interesting system to develop inquiry in the context of information systems security.

Although the research may take different forms and assume different goals, the use of national DNA databases is normally framed by a set of legislative initiatives that aim to specify their purposes of use and the parameters for their operation, maintenance, and management. Hence, legislation is usually the first deliberate step Governments take in order to create such artifacts, and as such legislation determines and delimits subsequent tactical or operational decisions regarding the use of the databases.

From an information systems security perspective, we can say that legislation plays the role of a regulatory control, that subsequently informs the selection of any informal, formal, or technical controls deemed necessary to protect the information manipulated in the context of DNA databases.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the legislation that was produced in order to establish a specific DNA database and to discuss its features and implications from an information systems security standpoint. The context selected for analysis was the Portuguese DNA profiles database.

The paper is organized as follows. After this introduction, the following section conducts a brief overview of DNA forensic databases in the world. Then, in Section 3, the theoretical and methodological approaches are described. The central part of the paper follows, with the analysis of the Portuguese legislation on DNA profiles database and the discussion of the findings. In the final section the conclusions of the paper are presented and future work opportunities are identified.

2. Overview of DNA Forensic Databases

The English police started to use the techniques of DNA profiling reported by Jeffreys in the context of criminal investigation in 1985 [Walter and Cram 1990].

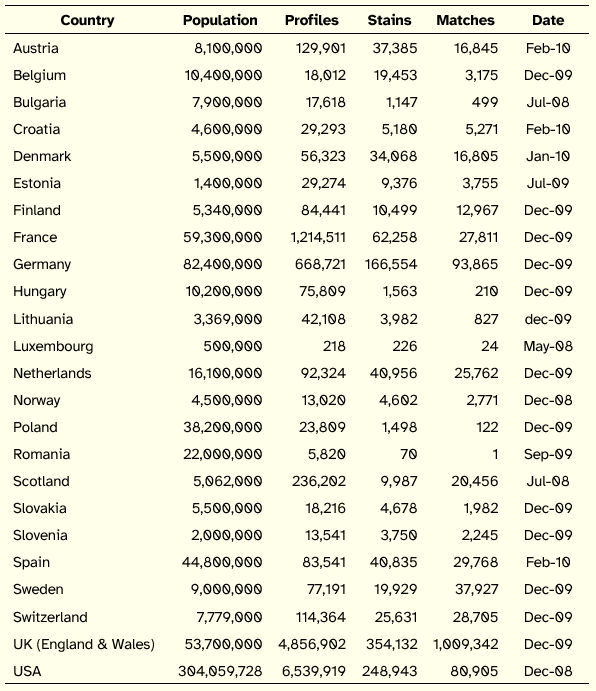

On 10 April 1995, the first operating national DNA forensic database was established in England and Wales. Four years later, this database contained over 700,000 profiles and achieved around 700 DNA matches each week [Martin et al. 2001]. Since then, this database has been constantly growing, having reached 4,856,902 profiles and 354,132 stains in December 2009 [ENFSI 2010].

Following the example of England and Wales, several countries have developed forensic DNA databases, such as Scotland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Austria, USA, Germany, Slovenia, France, Finland, Norway, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, Croatia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Spain, and Portugal.

Table 1: DNA Databases Statistics

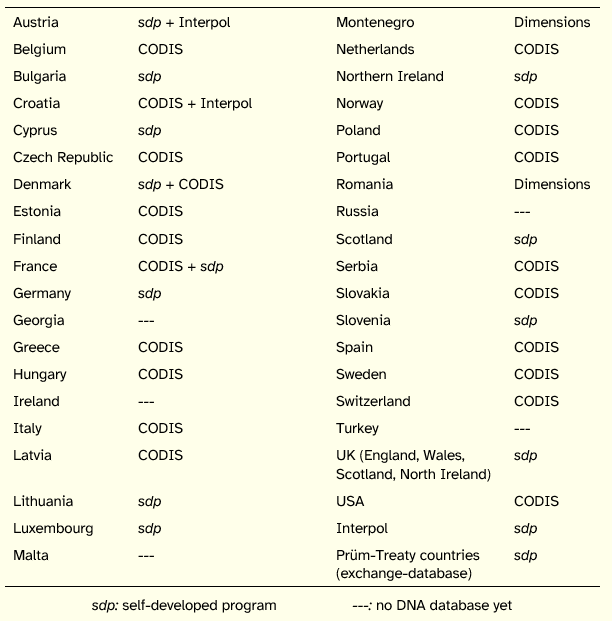

In order to store and compare DNA profiles, as well as to perform other functions, several software programs, commonly called DNA-database software, have been designed. These programs can be internally developed by a country to meet its own particular needs or they can be obtained from a producer.

Examples of DNA-database programs that can be obtained without cost are CODIS, which has been developed by the FBI, and STR-lab, a program developed in South-Africa [ENFSI 2010].

Programs which are or have been available in a commercial base are: FSS-iDTM, of the Forensic Science Service in the UK; Dimensions, of the Austrian company Ysselbach Security Systems; eQMS::DNA, of the Hungarian company Pardus, and fDMS-STRdb, distributed by the Czech Republic company Forensic DNA Service [ENFSI 2010].

Table 2 shows which DNA-database programs are in use by different countries (the sources of the data were [ENFSI 2010] and [USDJ 2008]).

Table 2: DNA Database Software in Use

3. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches

As previously stated, the purpose of this paper is to analyze the legislation that was produced in order to establish the Portuguese DNA database and to discuss its features and implications from an information systems security perspective.

After the delimitation of the study’s context—Portuguese legislation—the next main decision is to select the theoretical and methodological approaches that may guide the analysis of data and the synthesis of findings. Since the data to be analyzed in this paper are public legal documents related to the Portuguese DNA database, one may consider diverse modes of content analysis applicable to written documents, such as techniques that proceed from a previously established scheme of categories to those that build that scheme as the analysis evolves, a la grounded theory.

In this paper, the selected approach that guided the analysis of the legislation was the Theory of Action. To the best of our knowledge, the application of Theory of Action to legislation in the domain of information systems security constitutes a proposition of a novel approach to the interpretation of written data and, specifically, to make sense of information security legislative controls. In de Sá-Soares [2005], Theory of Action was applied to the analysis of information security standards, information security policies, and user behaviors in the realm of information systems security. In this paper, it is suggested that the same approach may be useful not only for guiding data analysis procedures on legislation, but also to ground and interpret the findings resulting from that analysis. The practical demonstration of this proposition may be understood as an additional aim of this paper.

In order to sustain the proposition advanced above, a brief description of Theory of Action will be presented, followed by the enunciation of the motivations and expected benefits of Theory of Action application to legislation in the field of information systems security.

The fundamental assumption of Theory of Action is that human beings hold theories or mental schemes that they use to design their actions [Argyris and Schön 1974].

According to this Theory, individuals develop and maintain theories of action with the assumption that they consist in theories about how to act effectively [Argyris 1982]. This effectiveness is perceived as the degree that consequences intended by an individual when doing certain action materialize in practice.

Theory of Action recognizes two kinds of theories of action: espoused theories and theories-in-use. Espoused theories are those that people claim to follow when designing their actions. Theories-in-use are those that people really use when designing their actions. The latter theories causally explain the action that is observed [Argyris 1996].

It should be noted that the difference between these two kinds of theories is not found in the distinction between what people say that should be done and what people really do. Both theories are at the same level, consisting in theories about action; however, theories-in-use should not be confused with concrete action. In fact, Theory of Action advises the study of behavior, not for its own interest, but for being the means that allows the inference of theories-in-use [Argyris and Schön 1974].

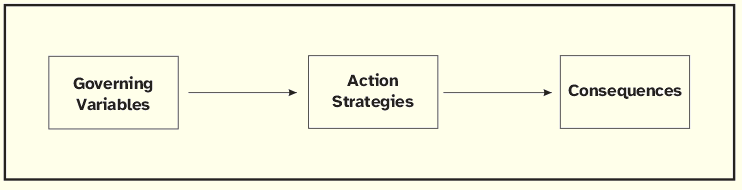

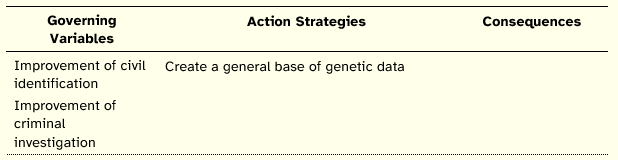

Methodologically, the procedures for analyzing data (in the present case legal texts) should follow the tenets of Theory of Action for the representation of espoused theories and theories-in-use, which may be modeled according to the construction illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Generic Model of Theories of Action

Adapted from Argyris et al. [1985, p. 84]

This representation is designated by action map and schematizes the components of a theory of action: governing variables—the values that an individual tries to satisfy, action strategies—understood as the means that lead to the satisfaction of those values, and consequences—the results of the actions undertaken [Argyris 1993].

Action maps are usually built in two phases. The first consists in the identification of the action map’s components and the second involves the ordering of each component according to the role it plays in the theory of action.

Another important concept of Theory of Action is that of actionability. This concept deals with the problematic of creating or producing in practice what one recommends or defends. The goal is to create knowledge, for instance in the form of propositions or recommendations, that enables the design of actions that produce the intended consequences.

In order to be actionable, it is necessary that recommendations stipulate the sequence of action strategies required to produce the intended consequences, be articulated in ways that make the causality transparent, specify the values that underlie and govern them, and that their embedded causality is testable in the daily context of practice [Argyris 2000, p. 239]. This means that recommendations should constitute a theory of action.

Although Theory of Action has been used to guide inquiry that focuses on individual or organizational behavior, in this paper it is suggested an extension of its use to legislation. The rational underlying this suggestion is that legal texts can be interpreted as documents that enclose espoused theories related to a specific area of action, in the present case the creation, use, maintenance, and management of DNA databases. Hence, the action maps associated with those texts will convey the explicit espoused theories of the legislator, in other words, the schema for the actions the legislator is trying to specify via the legal documents.

It should be stressed that the technique of document analysis to be applied needs to restrict itself to what is stated in the documents, avoiding inferences not clearly and fully supported by what is exposed in the legal texts. This is not only important for the rigor of analysis, but it also derives from the fact that a legal text, although potentially ambiguous as any non-mathematical text, should convey what it means.

From a theoretical point of view, a motivation for the use of Theory of Action on legislation results from its capacity to make explicit the causality embedded in legal texts. By focusing on the identification of the objectives being aimed by the legislation (the governing variables), the means allowed or not allowed to be undertaken in order to attain those objectives (the action strategies), the expected effects of enacting those means (the consequences), and on clarifying how these three constructs are interconnected, Theory of Action may prove useful in demonstrating the soundness of the rational underlying a particular piece of legislation. This closely relates to the above concept of actionability. By applying critical thought to the action map representing the espoused theory of a legislative control, we may be able to start discussing and anticipating potential difficulties in its observance or enforcement, really placing the reflection on its information security actionability.

Considering that any enacted law imposes a set of controls on the object of the legislation (the DNA database, in this case), it should be noted that the legal texts to be analyzed as enclosing espoused theories, in practice, should also enclose theories-in-use. Actually, due to the mandatory nature of legislative controls, it is expected that the espoused theory conveyed by the law at the time of its publication will be transformed in a theory-in-use once the law is in effect. In other words, the legal documents consist of designs for action whose authors expect to perfectly explain the actions that are subsequently observed—the publication of a law is accompanied by the supposition that its provisions will be observed. Hence, Theory of Action may also prove useful in the study of the compliance of legislative controls.

Armed with the action map of the law that conveys the respective espoused theory (and that will be the focus of this paper), the application of Theory of Action to the real actions that follow the enforcement of the law allows the inference of the corresponding theory-in-use. With these two actions maps—of the espoused theory that results from the legal text and of the theory-in-use that emanates from the specific actions of the agents in the realm of DNA database creation, use, maintenance, and management—we will have the instruments to compare both theories. Any differences between that claimed theory and the theory revealed by the application of the law should be closely scrutinized, since it may point to different governing variables trying to be met in practice, to unanticipated consequences, to misunderstandings in the action strategies to be executed, or to violations of the legal provisions, to name a few. This comparison may uncover issues that explain the effectiveness (or the lack of effectiveness) of particular legislation.

4. Portuguese DNA Profiles Database

The analysis of the Portuguese legislation on DNA profiles database proceeds in two phases. The first phase involves the analysis of the legal background. This analysis provides the context for understanding the work performed in the second phase, which corresponds to the review of the legislative process and to the analysis of its main results in the form of legal documents.

4.1 Legal Background

The consideration of the legal background of the Portuguese legislative process embraces two sets of documents regarding DNA profiling, fundamental rights, and genetic related legislation: those that emanate from the European Union (Portugal is an European Union Member State since 1986) and those that are in effect resulting from domestic legislative deliberations. In this section, these two sets of documents are considered successively.

4.1.1 The European Union Arena

In the European Union arena there are three documents related to DNA profiling that have a direct impact on Member States’ legislation.

The first document was issued in 1992 and focuses the use of DNA analysis in the realm of criminal justice [CE 1992].

The second and third documents were issued in 1997 and 2001, respectively, and both focus the exchange of DNA analysis results [CEU 1997, 2001]. These documents are analyzed below.2

Recommendation No. R (92) 1

Recommendation No. R (92) 1 was issued by the Committee of Ministers to Member States on 10 February 1992. This non-binding act of the Committee was on the use of analysis of DNA within the European framework of the Criminal Justice System.

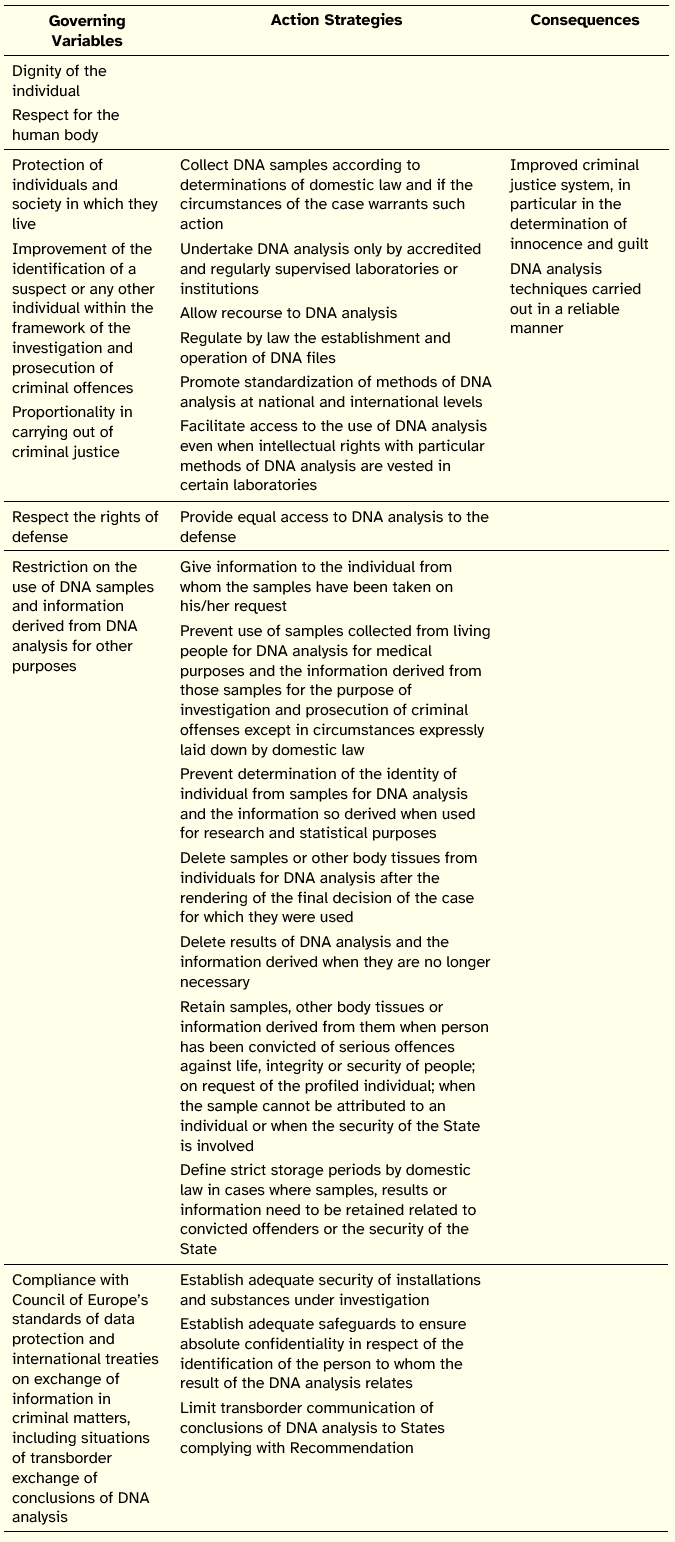

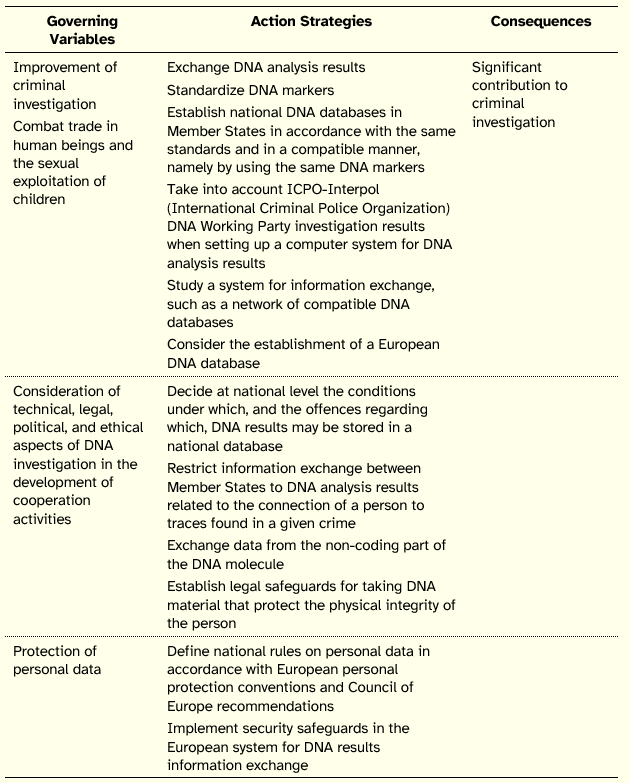

The action map of the Recommendation is presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Action Map of Recommendation No. R (92) 1

Although Recommendations are without legal force, they are negotiated and voted, which means they have political weight. This Recommendation may be understood as an instrument of indirect action for the use of DNA analysis by Member States.

Resolution 97/C 193/02

Resolution 97/C 193/02 was issued by the Council of Europe on 9 June 1997. The aim of this decision was to enable the exchange of DNA analysis results between Member States.

The action map of the Resolution is presented in Table 4.

Table 4: Action Map of Resolution 97/C 193/02

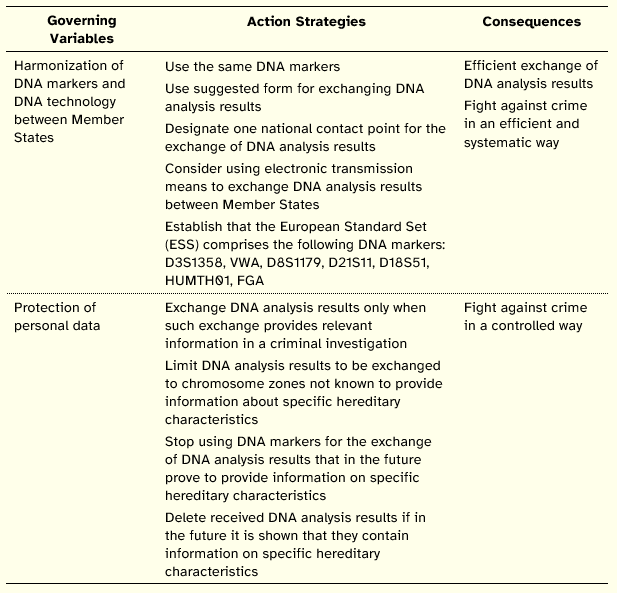

Resolution 2001/C 187/01

Resolution 2001/C 187/01 was issued by the Council of Europe on 25 June 2001. As with the previous Resolution, the objective of this document was to enable the exchange of DNA analysis results between Member States.

The action map of the Resolution is presented in Table 5.

The integrated analysis of these three action maps shows that the European Union proceeded into two stages in what concerns DNA profiling. First, it suggested Member States to consider the use of DNA analysis in the field of criminal justice. Second, it urged Member States to exchange DNA analysis results and to standardize procedures and databases.

In issuing these legal documents, the European Union subjected their intents to the satisfaction of the following objectives: respect the dignity of the individual (justified given the need to collect individual body samples), improvement of criminal justice system (the active objective which satisfaction could not put in danger the proportionality of investigation mechanisms and the rights of the defense), the restriction of the use of DNA samples and information to the stated purposes (the demarcation objective), the protection of personal data (given that all data manipulated are related to the individual), the acknowledgment of multiple nature of the phenomenon (it summons technical, legal, political, and ethical issues), and the harmonization of procedures.

Table 5: Action Map of Resolution 2001/C 187/01

In order to satisfy these goals, the documents stress five major types of actions: those that are concerned with the quality and reliability of DNA analysis technical procedures, those that enable the standardization of procedures between Member States, those related to information security (these include privacy protection actions and are applicable to samples, profiles, and personal data), those that specifically aim the exchange of DNA analysis results, in complement with actions that make more agile this exchange of results between Member States.

The documents are explicit in what concerns the expected consequences of undertaking these actions: an improved criminal investigation; a simultaneously efficient, systematic, and controlled combat against crime; and reliable DNA analysis techniques employed by all Member States.

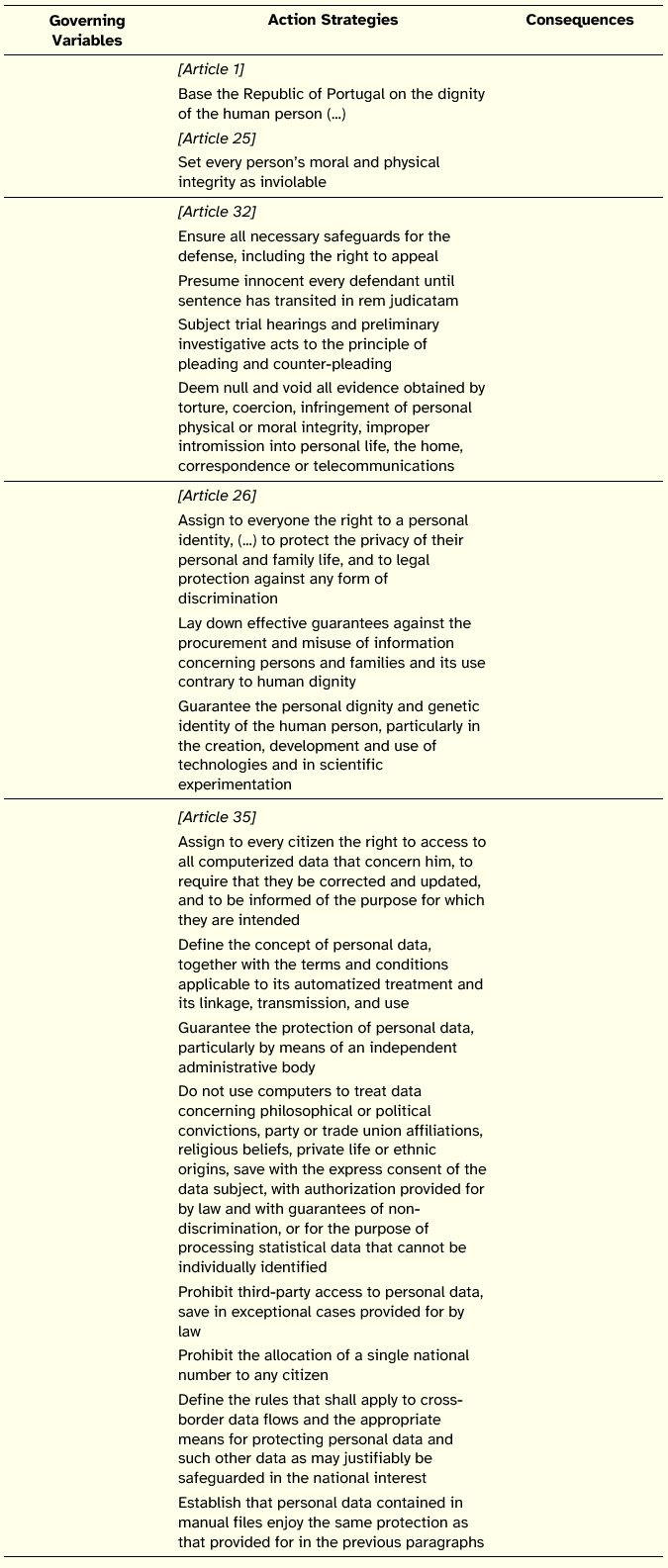

4.1.2 The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic

The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic dates from 1976 and its most recent revision was made in 2005 [CRP 2005].

The provisions of these articles that are pertinent to the subject of DNA profiling are transmitted in the action map of Table 6 (for better reference the identification of the articles was included).

Table 6: Partial Action Map of the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic

These action strategies highlight the importance of the dignity of the human person, the inviolable quality of personal integrity, the guarantees that assist the individual in the realm of criminal processes, the fundamental right of a person to personal identity (including the genetic identity), the need for protecting people against procurement and misuse of information, and the protection of personal data,3 with a special emphasis on computer-based data processing.

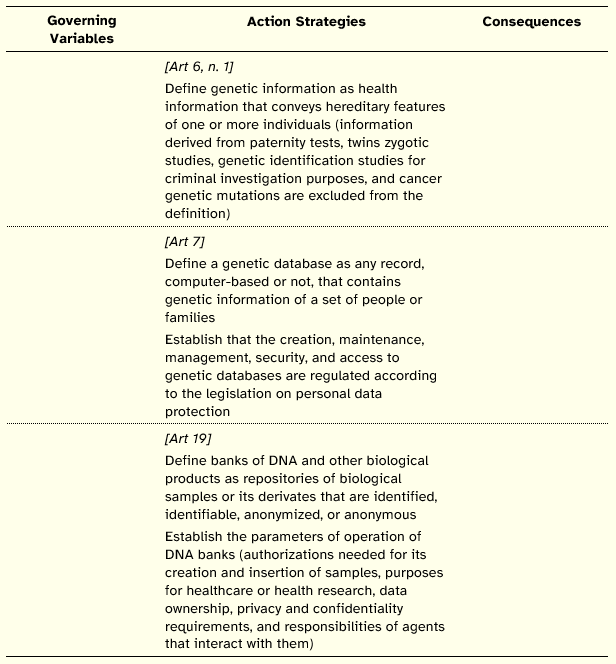

4.1.3 Law n. 12/2005

The provisions of these articles pertinent to DNA profiling are transmitted in the action map of Table 7 (for better reference the identification of the articles was included).

Table 7: Partial Action Map of Law n. 12/2005

These action strategies are relevant since this Law predates the Portuguese law on DNA Profiles database by three years and it advances a set of important definitions and procedures on genetic information and genetic material banks.

4.2 The Legislative Process

In this section the legislative process that led to the publication of the Portuguese act on DNA profiles database is reviewed. The first document that should be analyzed is the Programme of the XVII Constitutional Government [PCM 2005] since it conveys the political decision for establishing the database.

Programme of the XVII Constitutional Government

This disposition may be translated in the following action map (cf. Table 8).

Table 8: Partial Action Map of Government’s Programme

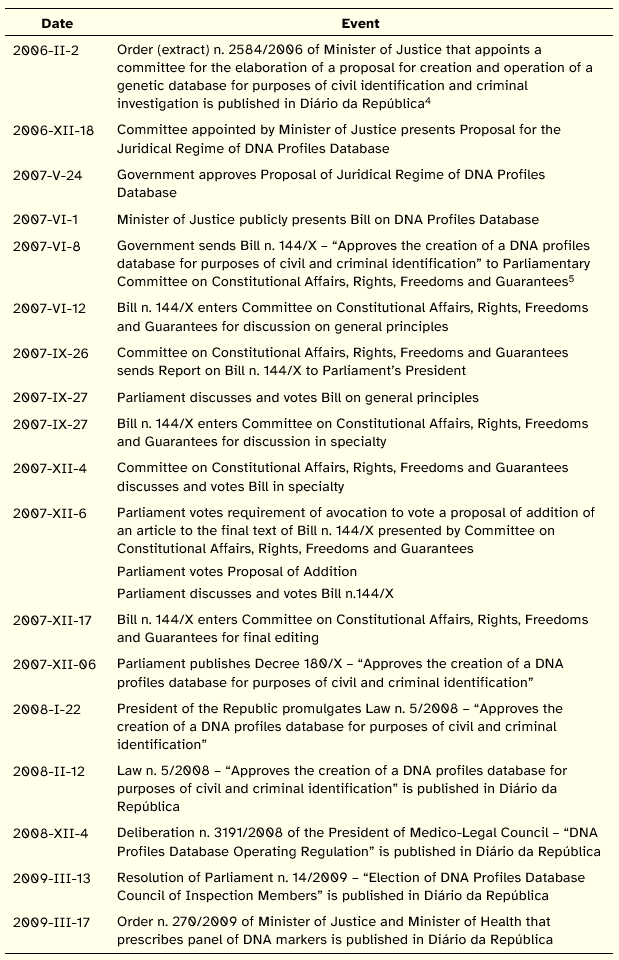

The Government’s Programme set the political background for the creation of the Portuguese DNA profiles database. The document that actually initiated the legislative process was Order (extract) n. 2584/2006 [DR 2006]. In the sequence of this document, a series of initiatives took place, as depicted in Table 9.

Besides Order (extract) n. 2584/2006, the other legal documents that will be analyzed are Law n. 5/2008 (the central legislative document) [DR 2008a], Deliberation n. 3191/2008 [DR 2008b], Resolution of Parliament n. 14/2009 [DR 2009a], and Order n. 270/2009 [DR 2009b]. These four documents constitute the Portuguese legal framework for the creation, use, maintenance, and management of the DNA profiles database.

Order (extract) n. 2584/2006

Table 9: Timeline of the Legislative Process

Law n. 5/2008

The text of the Law consists of 41 articles organized into eight chapters, titled: (I) General Provisions, (II) Collection of Samples, (III) Data Processing, (IV) Conselho de Fiscalização of DNA Profiles Database, (V) Biobank, (VI) Penalty Provisions, and (VIII) Final and Transitional Provisions. Chapter III (Data Processing) was further divided into four sections, namely (i) Constitution of Database, (ii) Insertion, Communication, Interconnection, and Access to Data, (iii) Conservation of DNA Profiles and Personal Data, and (iv) Database Security.

The institutional entities that the Law identifies as playing a direct role in the operation, monitoring, and inspection of the DNA profiles database are Laboratório de Polícia Científica da Polícia Judiciária (LPCPJ),6 Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal (INML),7 Conselho de Fiscalização (CF),8 and Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados (CNPD).9

The Law assigns to LPCPJ and to INML the responsibility for extracting DNA profiles from samples at national level.

The DNA profiles database will be physically located at INML (in the city of Coimbra), who will be responsible for the database, namely for the insertion, access, communication, interconnection, and elimination of data contained in the DNA profiles database; for assuring access to data by profiled people and for the update, correction, and modification of data contained in the database.

INML will have to comply with an internal regulation to be elaborated by the President of INML’s Medico-Legal Council and to be approved by Medico-Legal Council in six months after publication of the Law.

The conservation of the biobank, containing the samples, was also assigned to INML. However, the Law allows the establishment of protocols with other entities as long as they are able to comply with stated security and confidentiality requirements, impending on them the rules and limitations set forth by the Law under analysis.

CF will be a new independent administrative entity with authority powers, appointed by the Parliament and that will report only to Parliament. Its main attribution will be to control DNA profiles database and, concomitantly the activity of INML in the realm of DNA profiling. This entity will be formed by three citizens of recognized capacity in full employment of their civic and political rights and not pertaining to other supervisory councils or committees for a term of office of four years.

The legal statue of CF will be published in six months after publication of the Law under analysis. The headquarters of CF will be in the city of Coimbra and the human, administrative, technical, and logistics resources needed for its operation will be provided by INML, through transfer of Parliament’s funds to INML. Among CF’s competences there are the following: to authorize the practice of certain acts prescribed by Law, to emit opinion on DNA profiles database regulation, to ask and get information and clarifications from INML in order to prosecute its mission, to make inspection visits, to elaborate reports to be presented to the Parliament on the operation of DNA profiles database at least once per year, to command INML’s President to destroy samples, to present suggestions of legislative initiatives on DNA profiles database, and to emit opinion on any similar ongoing legislative initiative.

The responsibilities assigned to CNPD regard the emission of opinion on the list of DNA markers to integrate in DNA profiles files, provision of clarifications on personal data processing on INML’s request, emission of opinion on the communication of data contained in DNA profiles database to other entities for statistics and scientific research purposes, the emission of opinion on unforeseen interconnection of data contained in DNA profiles database, and the verification of the operating conditions of the database as well as the storage conditions of samples in order to certify the compliance with personal data protection provisions.

Article 2 of the Law provides a set of definitions in order to clarify concepts and expressions used on the legislative text, namely for DNA, sample, problem-sample, reference-sample, DNA marker, DNA profile, personal data, singular identifiable person, DNA profiles file, personal data file, DNA profiles database, biobank, and consent of profiled person.

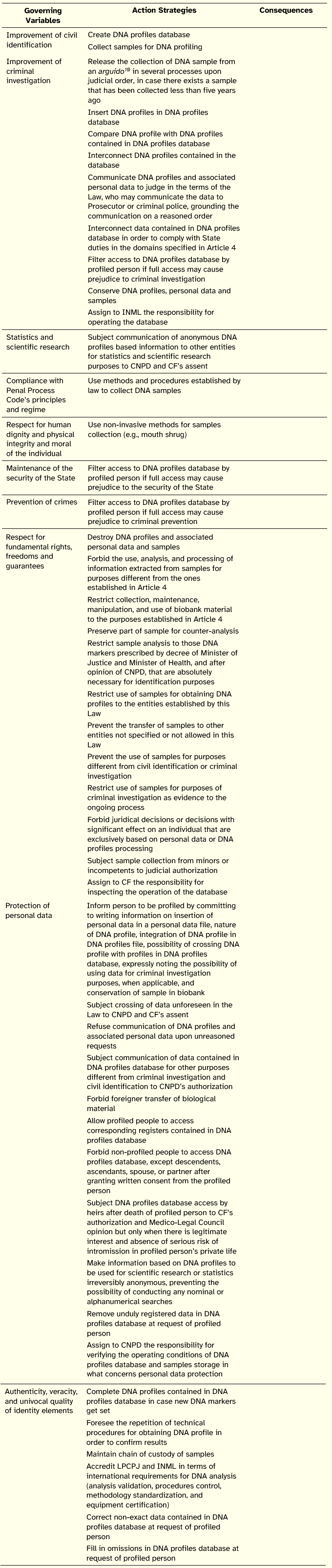

The Law’s action map is presented in Table 10.

Table 10: Action Map of Law n. 5/2008

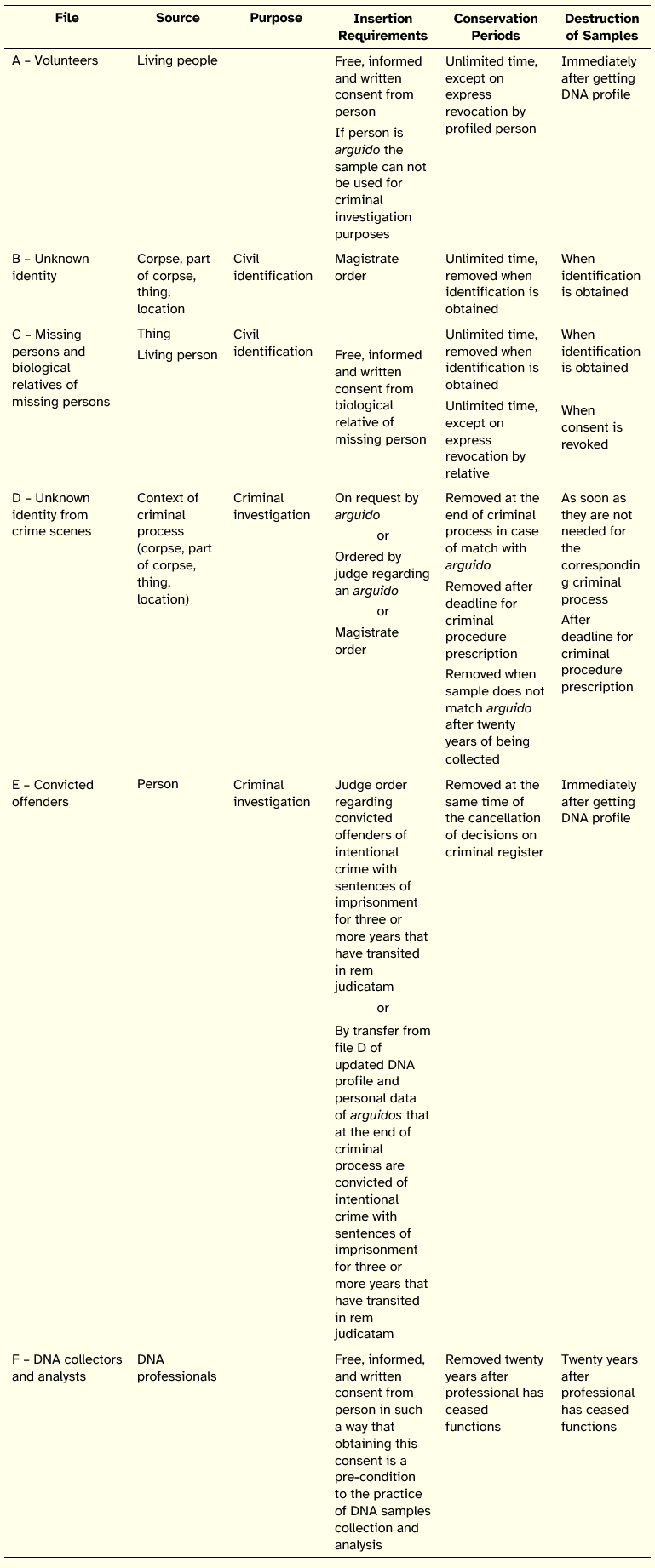

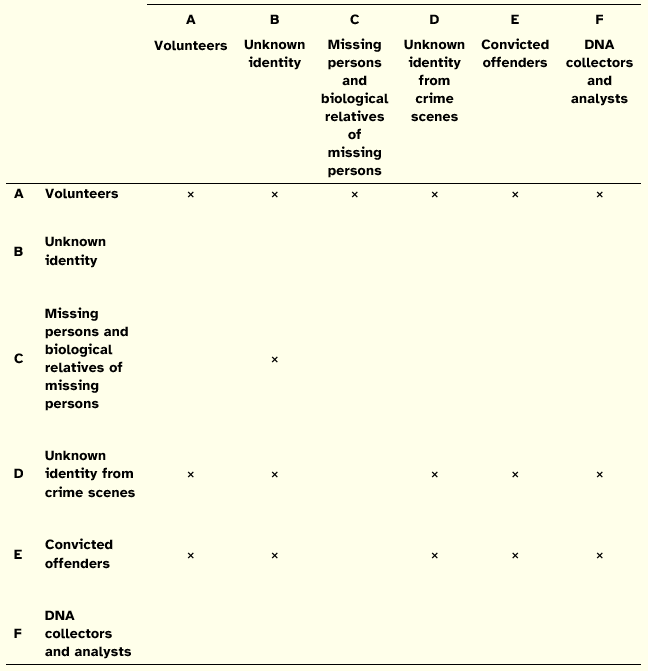

In what concerns the DNA profiles database contents, the Law defines six types of files. Table 11 lists those files, as well as the sources that will provide the samples for DNA profiling, the explicit purpose of the files, the requirements that need to be observed when inserting data to the files, the conservation periods for data contained in the files, and the timing for destruction of samples that where used to extract DNA profiles.

Table 11: Structure of Portuguese DNA Profiles Database

By considering the insertion requirements, conservation periods, and destruction of samples, the table clearly define the information life cycle of the data contained in the DNA database: in what situations new data is created, for how long it should be withheld, and when to proceed to the removal of DNA profiles and personal data, and to the destruction of biological samples. Actually, these criteria enclose a major part of the database information management tasks (the consideration of access rules would complete the spectrum of those tasks).

Although not explicitly stated, the purpose of file F is to clarify any situation of samples contamination. In what concerns the purpose of file A the Law is silent. However, this purpose can be discovered when one considers what parts of the DNA profiles database are allowed to be interconnected as established by the Law. The interconnections are indicated in Table 12. The rows and columns refer to the six types of files that constitute the DNA profiles database (the interconnections allowed should be found out by reading the table from rows to columns).

Table 12: Allowed Interconnections between DNA Profiles Database Files

The database security action strategies are espoused in the Law under two headings: information security and secrecy duty, as presented below:

Information security

Segregate logically and physically DNA profiles from corresponding personal data

Forbid identity elements of profiled person on DNA profiles file

Forbid searches of DNA profiles file by name

Prevent unauthorized consultation, modification, suppression, addition, destruction, or communication of data contained in DNA database

Prevent unauthorized reading, disclosure, copy, alteration, or elimination of data supports and unauthorized transportation of data supports

Prevent unauthorized introduction, acknowledge, disclosure, alteration, or elimination of personal data

Prevent the use of data processing systems by unauthorized personnel

Restrict personnel access to data to the exercise of their legal attributions

Restrict data transmission to authorized authorities

Log personal data insertion in data processing systems in terms of what was inserted, when, and by whom

Subject the practice of collection and analysis of DNA samples and of other similar functions that presupposes direct contact with genetic data support to securing free, informed, and written consent from those professionals

Secrecy duty

Restrict the communication and disclosure of DNA profiles and personal data contained in the database to the terms established in this Law and in compliance with the Personal Data Protection Law

Bind samples collectors, professionals involved in obtaining DNA profiles, personnel responsible for the insertion, communication, interconnection, and access to DNA profiles or personal data files, and CF members to professional secrecy, even after they cease their professional functions or after term of office, respectively

Punish those who disclose information contained in DNA profiles database under Penal Code and Personal Data Protection Law

Punish violations of personal data protection norms under Personal Data Protection Law

The biobank security action strategies made explicit by the Law are the following:

Prevent immediate identification of person from sample

Prevent unauthorized people to access biobank facilities

Store samples correctly, safely, and securely

Correctly and securely transport samples to INML

Restrict access to laboratories and storage premises of samples to specialized personnel, upon coded identification and previous authorization by the person in charge of the service

Still in what concerns the secure database action strategies it is possible to recognize safeguards that target installations and areas, media (data supports), equipment (data processing systems), information, personnel, and information manipulating activities, namely the ones related to information insertion, transportation, transmission, removal, and destruction.

Considering the action map of the Law (cf. Table 10) it is evident that the text does not state any consequences for the execution of the action strategies that proposes. Although this is indeed the case, the Bill that originated the Law included the identification of several consequences. This identification was advanced in the Preamble of that Bill, a part that was discarded in the final editing of the legislative text.

Focusing the attention on the other components of the action map, it is possible to conclude that the improvement of civil identification and criminal investigation are the dominant objectives of the Law and the espoused reasons for it come into being. However, they are not the sole values that the legislator aimed to satisfy. These values have to be fitted together with the respect for several constitutional rights, as well as with the assurance of several qualities of the identity elements maintained in the database and manipulated by combinations of people and equipment. Besides these values, the action map points some lateral objectives that must be satisfied, some for the sake of science, others for compliance with more global concerns, like the security of the State and the conformity with the law.

In order to attain that set of goals, the action map captured a list of action strategies. A limited subset of these strategies directly targets the active objectives of the Law. A significant subset deals with means for assuring the respect for constitutional rights. A small subset of other strategies exists for the satisfaction of the previously referred global concerns. However, it should be noted that there is a significant and diverse subset of action strategies that focuses the information security of the database (understood at large, encompassing data, equipment, media, personnel, and facilities controls). These action strategies play a fundamental role in achieving several of the action map’s governing variables, namely the security of identity elements, the protection of personal data, and the assurance of the authenticity, veracity, and quality of identity elements, principles that authors like Parker [1998] and Dhillon and Backhouse [200] have argued should be considered alongside with the traditional information security principles of confidentiality, integrity, and availability. By acting directly on the achievement of these objectives, information security action strategies become enablers (necessary, although not sufficient) not only of the improvement of identification processes, but also for the preservation of fundamental rights of people.

A significant part of the information security action strategies conveys rules for controlling access to the data by database professionals, the judicial system, authorities, profiled people, profiled people relatives, third parties, and foreigner governments. Together with provisions for inserting, maintaining, removing information, and destroying samples, these action strategies establish a program for the management of the information life cycle in the context of the DNA database.

Deliberation n. 3191/2008

As established by Law n. 5 /2008, INML’s Medico-Legal Council should elaborate and approve the Regulation of Operation of DNA Profiles Database. The date of approval of this document was 15 July 2008 and the publishing date in Diário da República, as an INML’s Deliberation, was 3 December 2008 [DR 2008b].

The Regulation has 19 articles and four annexes. The articles are organized into six chapters, titled (I) General Provisions, (II) Assumptions to Obtain DNA Profiles, (III) Performing Analyses, (IV) Removal of DNA Profiles and Personal Data, (V) Personnel, and (VI) Final Provisions.

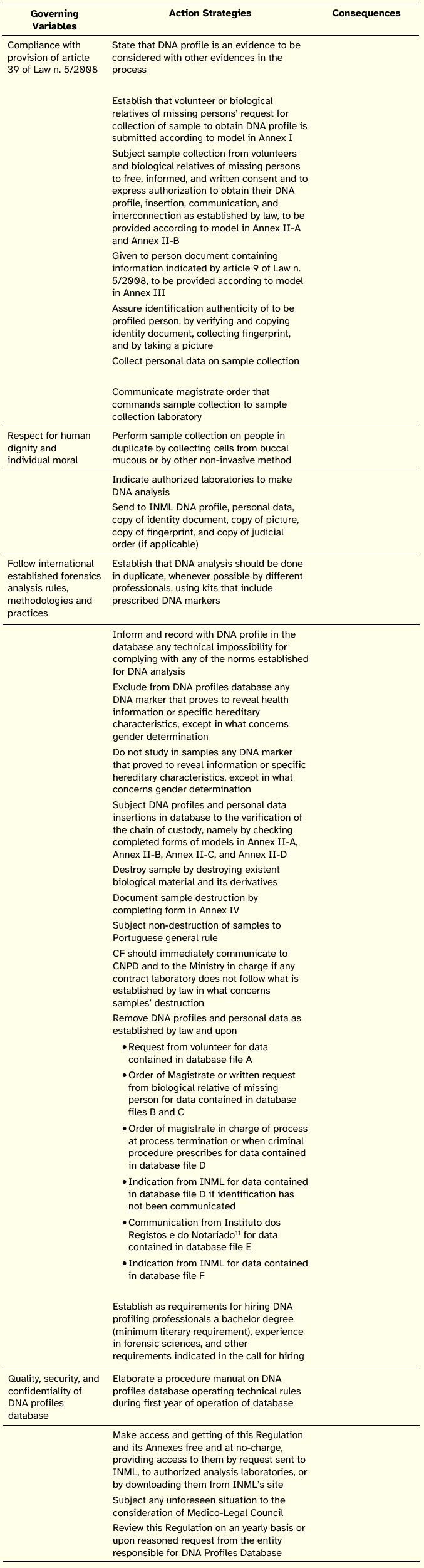

The Deliberation’s action map is presented in Table 13.

Table 13: Action Map of Deliberation n. 3191/2008

The action map shows that an important part of the procedures concerns the production of several documents, according to a set of models whose layout is provided in the annexes of the Regulation.

As expected, the Regulation presents as its main governing variable the compliance with article 39 of Law n. 5/2008 that established the need to approve the regulation of operation of DNA profiles database. The other governing variables espoused in the Deliberation refer specific values that some of the espoused action strategies should satisfy.

The analysis of the action strategies suggests a set of procedures that, to a certain extent, replicate part of the action strategies contained in the action map of Law n. 5/2008. This is hardly surprising, since the Regulation must be aligned with the provisions of that Law.

Albeit a considerable number of the action strategies focuses the sample collection procedures and in particular the data recording aspects of those procedures, the Regulation does not address specific concerns with the information security of the database. Although the Law prescribed an extensive set of action strategies aimed to secure the database, to protect personal data, and to preserve or improve the integrity of the identity elements, none of these action strategies were further developed or detailed at the level of the Regulation. Actually, aspects like the segregation of the database contents, the procedures for inserting data into the information processing system that interfaces with the database, the specification of controls aimed to preserve the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the database, the access controls that will mediate the use of information contained in the database, the use of DNA-database software, the maintenance of the software, the communications and operations management, and incident handling are not addressed by the Regulation.

Apparently, the provision of mechanisms and controls for assuring the security and functioning of the database from an information systems perspective was sidelined, and instead it was given priority to the technical work undertaken by DNA collectors and analysts. Of course, one might argue that a substantial part of those mechanisms and controls presents a sensitive nature that goes against its public treatment. This could be the case, however, it still there would be space for specifying roles, responsibilities, and general policies that should guide the planning, development, implementation, and evaluation of those mechanisms and controls. Alternatively, it is possible that the authors of the Regulation left these concerns and provisions to the procedural manual on DNA profiles database operating technical rules to be elaborated during the first year of operation of the database. If this is the case, the transposition of the information systems requirements specified in the Law n. 5/2008 will be one more level further apart.

Resolution of Parliament n. 14/2009

In this Resolution, published in Diário da República on 13 March 2009, Portuguese Parliament designated the three individuals that will compose DNA Profiles Database CF.

Order n. 270/2009

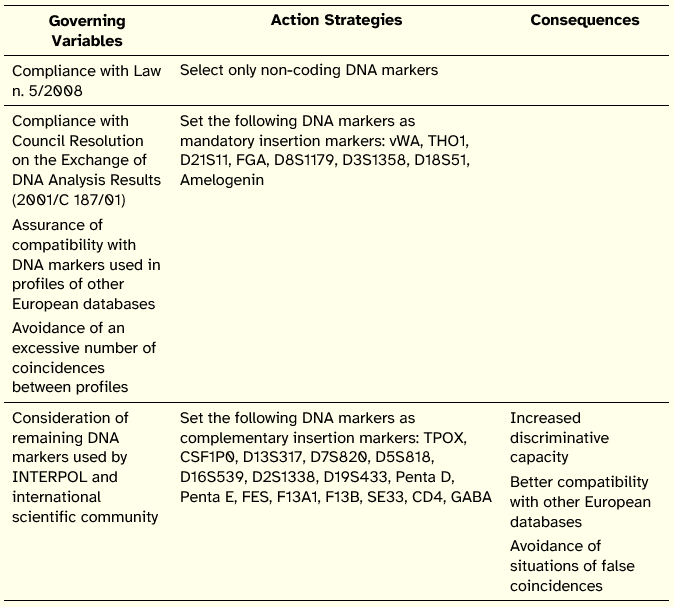

This document, published in Diário da República on 17 March 2009, and signed by the Minister of Justice and by the Minister of Health, prescribes the DNA markers that will be integrated in the DNA profiles files of the DNA Profiles Database.

The DNA markers were organized into two categories: mandatory insertion markers and complementary insertion markers.

The action map of the Order is shown in Table 14.

Table 14: Action Map of Order n. 270/2009

The governing variables of this action map, together with the consequences advanced to the action strategy regarding the setting of complementary insertion DNA markers, show two interesting characteristics. One is the clear intention of compliance with European Union resolutions to facilitate the exchange of DNA analysis results, an end that depends heavily on compatibilization efforts by Member States. The other is the concern with the effectiveness of the DNA profiles database, suggested by the goal of reducing coincidences and the anticipated consequence of an increased discriminative capacity of the identification process.

In a certain way, this legislative document marks the point where the necessary conditions for the operation of the DNA profiles database have been met. Since Law n. 5/2008 required the appointment of CF and the approval of the Regulation, with these two last documents the legislative controls of the Portuguese DNA profiles database are in place.

5. Conclusion

This paper has reviewed the main legislative pieces that support and regulate the creation, use, maintenance, and management of the Portuguese DNA profiles database.

The application of Theory of Action allowed the interpretation of the legal documents in terms of three cornerstones: the explicit values or objectives that the legislator aims to satisfy (the governing variables), the means devised to achieve that satisfaction (the action strategies), and, wherever identified, the expected outcomes of those means (the consequences).

It is argued that Theory of Action provides an interesting approach to make sense of legislation and, considering the particular subject of this paper, to analyze and interpret legislative controls in the domain of information systems security.

The action maps that were constructed clarify the dependences between the analyzed legal texts, making possible to trace how previous and encompassing legislation, such as European directives, fundamental constitutive text, and prior national acts, provide the context for subsequent legislation, conditioning its formulation and guiding its alignment in a web of legal texts.

Another finding was the multiple objectives nature of the legal texts, namely the central one (Law n. 5/2008), some of them consisting of potential conflicting goals (such as the purpose of improving criminal investigation and civil identification; the purpose of respecting fundamental rights, freedoms, and guarantees; and the purpose of protecting personal data) and the specific provisions established for their achievement.

An additional finding was that some of the documents do not enclose a complete theory of action, since some of its components are missing, raising the question of its actionability and suggesting the working proposition that legislation may, indeed, consist of incomplete theories of action.

This work suggests several opportunities for developing further research on DNA profiles databases. Three specific opportunities are presented below.

First, it would be important to study the practical consequences of the application of Law n. 5/2008, as well as any associated difficulties or problems. This would allow finding out if the espoused theory enclosed in the Law (one of the results of this paper) is congruent with the theory-in-use that its application might led to infer. The application of Theory of Action in this post-legislative publication study could provide the means to link legislation and behavior. Besides the analysis of the practical consequences, it would be important to monitor the evolution of the legislation in order to verify if new legislative initiatives take place, so that any modifications of the espoused theory may be traced to adjustments in the action strategies (and to the causes of those adjustments) or in the governing variables (probably as evidence of extensions or restrictions of stated purposes of the DNA profiles database). This opportunity is clearly related to the study of the actionability of the Law, i.e., the potential that the analyzed legislative controls have to produce in practice what they prescribe in legal form.

A second opportunity for future research would be to undertake an information systems security evaluation of the use of the Portuguese DNA profiles database. This exercise would revise how well the requirements and procedures prescribed by the law in terms of information security were translated and put in effect in practice. This inquiry could prove useful in clarifying the transformational process that takes place in order to translate the generic and eventually ambiguous security requirements established by legislation into specific technical, formal, and informal security controls.

The third opportunity for future work would be to apply the theoretical and methodological approach selected for this study to analyze equivalent legislation of other countries that have implemented DNA databases. It is expected that the construction of the respective action maps, with the characterization of the competences and roles of the major players in the operation of the database and the identification of criteria for sample collection, retention, and destruction, and of criteria for insertion, access, conservation, removal, communication, interconnection, and exchange of data in the database may provide the operational elements required for the comparison of those different legislative controls. Eventually, these may allow clustering countries’ legislation on DNA databases in terms of purposes, procedures, and expected benefits and costs.

References

Argyris, C. (1982). Reasoning, Learning, and Action: Individual and Organizational. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for Action: A Guide to Overcoming Barriers to Organizational Change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Argyris, C. (1996). Actionable Knowledge: Design Causality in the Service of Consequential Theory. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 32(4), 390–406.

Argyris, C. (2000). Flawed Advice and the Management Trap: How Managers Can Know When They’re Getting Good Advice and When They’re Not. New York: Oxford University Press.

Argyris, C., R. Putman and D. M. Smith (1985). Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Argyris, C. and D. A. Schön (1974). Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Astbury, W. T. (1947). X-ray analysis of nucleic acids. Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology 1, 66–76.

CE (1992). Recommendation No. R (92) 1 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Use of Analysis of Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) within the Framework of the Criminal Justice System. Council of Europe, 10 February 1992.

CEU (1997). Council Resolution of 9 June 1997 on the Exchange of DNA analysis results (97/C 193/02). Council of the European Union, Official Journal C 193, 24/06/1997, 2–3.

CEU (2001). Council Resolution of 25 June 2001 on the Exchange of DNA Analysis Results (2001/C 187/01). Council of the European Union, Official Journal C 187, 3/07/2001, 1–4.

CEU (2008). Council Decision 2008/616/JHA of 23 June 2008 on the implementation of Decision 2008/615/JHA on the stepping up of cross-border cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and cross-border crime. Council of the European Union, Official Journal of the European Union 210, 6/08/2008, 12–72.

Dahm, R. (2008). Discovering DNA: Friedrich Miescher and the early years of nucleic acid research. Human Genetics 122(6), 565–581.

Dhillon, G. and J. Backhouse (2000). Information System Security Management in the New Millennium. Communications of the ACM 43(7), 125–128.

DR (1998). Lei n.º 67/98, de 26 de Outubro—Lei da Protecção de Dados Pessoais. Diário da República—I Série-A, N.º 247, 26 October.

DR (2006). Despacho (extracto) n.º 2584/2006 (2ª Série). Diário da República—II Série, N.º 24, 2 February.

DR (2008a). Lei n.º 5/2008—Aprova a criação de uma base de dados de perfis de ADN para fins de identificação civil e criminal. Diário da República—1.ª série, N.º 30, 12 February.

DR (2008b). Deliberação n.º 3191/2008—Regulamento de funcionamento da base de dados de perfis de ADN. Diário da República—2.ª série, N.º 234, 3 December.

DR (2009a). Resolução da Assembleia da República n.º 14/2009—Eleição dos membros do conselho de fiscalização da base de dados de perfis de ADN. Diário da República—1.ª série, N.º 51, 13 March.

DR (2009b). Portaria n.º 270/2009. Diário da República—1.ª série, N.º 53, 17 March.

CRP (2005). Constituição da República Portuguesa. http://www.parlamento.pt/Legislacao/Paginas/ConstituicaoRepublicaPortuguesa.aspx.

ENFSI (2010). DNA-Database Management Review and Recommendations. ENFSI DNA Working Group, April.

FSS (2008). Colin Pitchfork—first murder conviction on DNA evidence also clears the prime suspect. Forensic Science Service http://www.forensic.gov.uk/html/media/case-studies/f-18.html (Accessed on 18 May 2010).

Hershey, A. and M. Chase (1952). Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. The Journal of General Physiology 36(1), 39–56.

Jeffreys, A., V. Wilson and S. Thein (1985). Individual-specific Nature 316(6023), 76–79.‘ Lorenz, M. G. and W. Wackernagel (1994). Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiology Reviews 58(3), 563–602.

Parker, D. B. (1998). Fighting Computer Crime: A New Framework for Protecting Information. New York: Wiley.

PCM (2005). Programa do XVII Governo Constitucional. Presidência do Conselho de Ministros, http://www.portugal.gov.pt/pt/Documentos/Governos_Documentos/Programa%20Governo%20XVII.pdf

de Sá-Soares, F. (2005). A Theory of Action Interpretation of Information Systems Security. PhD Thesis. University of Minho, Portugal.

TNF (1968). The Nobel Prize Winners in Physiology or Medicine 1968. The Nobel Foundation, http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1968/ (Accessed on 14 May 2010).

USDJ (2008). CODIS Brochure. United States Department of Justice/Federal Bureau of Investigation, http://www.fbi.gov/filelink.html?file=hq/lab/pdf/codisbrochure2.pdf (Accessed on 19 May 2010).

Walker, C. P. and I. Cram (1990). DNA profiling and police powers. Criminal Law Review, 479–493.

Watson, J. D. and F. H. C. Crick (1953). A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 171 (4356), 737–738.

Webster (2002). Webster’s New World College Dictionary, fourth edition. Cleveland: Wiley Publishing.

Endnotes

1 Given the volume of stored information and the types of DNA profiles processing functions, especially the search operations, the repositories of DNA profiles and personal data (symbolic data) naturally assume the form of an IT-artifact.

2 A fourth document—Council Decision 2008/616/JHA of 23 June 2008 [CEU 2008]—could also be considered. This document, that has origins in the Prüm Treaty or Convention, includes provisions on DNA profiles, but since its approval was after the publication of the Portuguese law on DNA profiles database, it will not be analyzed in this paper.

3

4 Diário da República (Daily of the Republic) is the official journal of Portugal, where Laws, Decree-laws, decisions of the Constitutional Court, Regulations, public contracts, etc., are published.

5 This is a Parliament’s standing committee composed of 20 to 30 Members of the Parliament that has competences on constitutional and institutional affairs; human rights; justice and prison related affairs; internal affairs; European space of freedom, security and justice; immigration, integration policies and intercultural dialogue; and equality of opportunities.

6 Scientific Police Laboratory of Judicial Police—http://www.policiajudiciaria.pt

7 National Institute of Forensic Medicine—http://www.inml.mj.pt

8 Council of Inspection

9 Data Protection National Commission—http://www.cnpd.pt

10

11 A public institute that executes and monitors policies related to registration services (civil identification, civil registration, nationality registration, land registration, commercial registration, etc.).