Original source publication: de Moura, F. L. and F. de Sá-Soares (2022). Semantic and Syntactic Rules for the Specification of Information Systems and Technology Competencies. IADIS International Journal on Computer Science and Information Systems 17(1), 50–64.

The final publication is available here.

Semantic and Syntactic Rules for the Specification of Information Systems and Technology Competencies

Centro ALGORITMI, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

There is currently a great demand, which looks set to continue to grow in the near future, for professionals in the Information Systems and Technology area. The search for these professionals faces the difficulty of hiring individuals suited to the company’s culture and who have a set of competencies that can add value to the company in the short term, with the possibility of a lasting relationship and with gains for both parties, employee and employer. However, several references that assist in the structuring of professional profiles do not follow a standard when using the concepts needed to describe professional competencies, falling short to provide a more accurate support to the process of hiring and developing professionals. This work analyzes eight competency frameworks, reviews the definitions of competency-related concepts and proposes a competency grammar to standardize and clarify the specification of competencies, by resorting to Backus-Naur Form. To validate the proposal, Information Systems and Technology professionals, as well as practitioners from four other professional areas, reported attributes of their occupations, in light of the adopted definitions and observing the proposed grammatical rules.

Keywords: Competency; Information Systems and Technology; Information Systems and Technology Competency; Competency Grammar; Backus-Naur Form

1. Introduction

By studying several well-known Information Systems and Technology (IST) competency-focused frameworks in the search for definitions of competency-related concepts, we found that different concepts form the structure of those frameworks. The lack of rigor when applying the concepts related to the competencies of individuals led us to resort to dictionaries, seeking primary definitions for the concepts. In an effort to obtain a unified approach to the variety of concepts addressed in this work, as well as to grasp better ways to formulate (writing) them, we advanced revised definitions for the concepts, based on the reviewed literature. This allowed us to structure the construct of competency in the realm of the IST professional area.

In this paper, we argue that one way to distinguish the attributes characterizing professionals’ competencies is the way of writing the attributes that compose the competency construct. We advocate that the attributes associated with job competencies, such as expected actions from a professional, knowledge requirements, individuals’ features, or even job-related objects, may have their writing standardized, and that this will assist in their classification in one of the main concepts reviewed in this work. To this end, we propose that Backus-Naur Form (BNF), a meta-syntax notation, can be used to define criteria–a grammar–to govern the writing of concepts that compose the competency construct. Thus, the research question that this work aims to answer is the following: Is a Backus-Naur Form competency grammar able to assist in the identification, classification and writing of IST professional attributes? Aiming to answer the research question, we turned to IST professionals, asking them to revisit their professional routines and to use the BNF competency grammar to map their responsibilities in the workplace, i.e., all that is required to meet the daily demands of their job functions. Afterwards, with the intention of increasing the generalization degree of the competency grammar, we also engaged professionals from four areas not related to IST.

We delineated the competency-related concepts based on several competency frameworks and grounded in definitions found in dictionaries. In the next section of the paper, we summarize the literature review, briefly describing the competency frameworks, and identifying the dictionaries that provided support material for the definition of concepts. The main concepts are also presented, with BNF being introduced as the notation for specifying the rules of writing the instantiations of the concepts involved. After the literature review, the section on competency grammar sets forth the writing rules for each of the reviewed concepts. Also in that section, we propose a decision tree to aid in the classification of words or sentences related to the practice of professionals. Next, we describe initial efforts to validate the competency grammar in use. In the final section, conclusions, limitations of the study and ideas for future work are pointed out.

2. Literature Review

The definition of the concepts was considered a requirement to start this work. In what concerns the competency frameworks, it was noted that these references approach the concepts differently, resulting in different definitions for the same concept, as well as different concepts with the same definition. This divergent approach to the concept of competency complicates the establishment of professional profiles, which can lead companies to experience additional difficulties in finding the most suitable professional for their demand. Seeking to strengthen the path leading to the definition of concepts, it was also necessary to use dictionaries, since dictionary-based definitions are, to a certain extent, agnostic, i.e., they are not tied to or influenced by the specific purposes or central themes underlying competency frameworks.

The following subsection addresses the eight competency frameworks reviewed in this work (O*NET, ROME, e-CF, SFIA, iCD, MSIS2016, IS2020, and IT2017), paying particular attention to the approach adopted in each framework to the concept of competency and to the central theme that each framework focuses on.

2.1 Competency Frameworks

The O*NET framework is supported by the United States Department of Labor [2020], receiving constant updates. This framework has professional occupation as its central theme, but it involves several other concepts that refer to characteristics and attributes expected to be found in professionals. Some complementary concepts are based on the RIASEC types (Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional) proposed by Holland [1997]. The O*NET architecture also integrates training courses recommended for the occupations covered by the framework, pointing out the level of training normally required for hiring professionals. Concerning hiring, it also provides information regarding to wages, employment trends, and job openings. This framework helps individuals to obtain information about which career to pursue, the tools typically used in the job, routine tasks that the professional must perform, as well as routine situations that a professional might face on a daily basis. O*NET has mapped 1016 professional occupations, which are grouped into 16 groups. For each group, possible career paths, the so-called Career Pathways, are identified.

With similar characteristics, there is the Répertoire Opérationnel des Métiers et des Emplois (ROME) [ETALAB 2020], provided by the French government. This framework also uses the RIASEC types, but it constrains the concept addressed to its central theme, namely occupation. For the professional occupation, the framework proposes how to enter the career, indicating the necessary training and conditions for the exercise of the profession, having in mind the physical and technical skills required by the occupation. Basic competencies and specific competencies for the occupation are also mapped, in addition to indication of situations in the work environment and related occupations, based on the professional attributes in common between occupations and pointing out what would be required for a career evolution, enabling a professional to move to another occupation. An additional similarity between ROME and O*NET concerns the grouping of occupations. In ROME there are 509 professional occupations mapped, divided into 17 large groups. Both ROME and O*NET are overarching frameworks, addressing occupations in manifold professional areas, not just activities within the IST practice domain.

Assigning the concept of competency as the central theme of the framework, the European e-Competence Framework (e-CF) [European Union 2016], specifically aimed at the area of IST, sets forty-one different competencies. In addition to these competencies, the e-CF characterizes 30 illustrative profiles that can be held by IST professionals. Each professional, according to the framework, must have a different group of competencies, and for each competency, there will be a demand that may vary, according to five different levels of proficiency. The framework structures the competency information into four dimensions, with the first dimension indicating the macro process in which the competency falls (Plan, Build, Run, Enable, or Manage). The second dimension indicates the skills required for the professional occupation, and the third dimension details, for each skill, the expected proficiency levels, which may vary from level 1 to level 5. The detailing of the occupation also suggests which are the expected deliveries for each occupation, considering three different moments that the professional may experience in their occupation, being Accountable, Responsible, or Contributor. There is also a summary of the main tasks that a professional will have to perform during his/her professional activity and more general data, which relates to specific information with the required competency and the exercise of the occupation. It is worth mentioning that the third dimension of the framework is not limited to the technical characteristics of the occupation, since it suggests which attitudes the professional should demonstrate when performing his/her professional attributions. The fourth dimension provides a set of knowledge and skill items as example and basis for each competency of e-CF. This framework gave rise to a European standard, identified as EN16234, highlighting the relevance of the knowledge accumulated over more than 10 years of work by professionals in IST from different regions of Europe.

Assuming skill as the central theme, there are the Skill Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) [SFIA Foundation 2021] and the i-Competence Dictionary (iCD) [Hayashiguchi et al. 2018], both specific to the IST professional area. The support provided by SFIA is based on the mapping of 121 skills, grouped into 19 subcategories and, then, into six categories. Associated to each skill there are levels of responsibility, with each level embodying increased responsibility, accountability, and impact, which are divided into the following attributes: autonomy, influence, complexity, business skills, and knowledge. It is through these attributes that the skills are described, and it becomes possible to define professional profiles. The levels of responsibility are defined according to the skill. However, some skills do not have attributes defined right from level 1, but only from more highest responsibility levels, suggesting that a professional with limited experience would not qualify for exhibiting certain skills. The levels of responsibility have a denomination that makes clear the expected performance of the professional at each level, which goes from 1 to 7, being, respectively: Follow, Assist, Apply, Enable, Ensure/Advise, Initiate/Influence, and Inspire/Mobilise. SFIA provides a matrix that relates the levels of responsibility to the attributes of each skill, making clear what is the technical capacity and expected behavior of professionals in the IST domain.

The iCD, although having skill as its central theme, proposes a different approach by listing the tasks associated with each individual skill. This framework includes 84 skill categories, divided into 14 classifications and four categories. In all, the categories include 442 different skills. There is also an interesting relationship proposed by the iCD, which assigns, for each skill, a necessary set of knowledge items. The framework has mapped more than ten thousand and one hundred items, each one assigned to one or more skills. There is also the Job List and Job Category, which, like the knowledge items, are also related to the skills list. Regarding the proficiency level defined for the skills, iCD also uses seven levels, which from level 1 to level 4 divide proficiency characteristics between Technology, Methodology, and Related Knowledge. From level 5 onwards there is no division between the categories, having only a description for the proficiency level. Considering the iCD as a glossary of tasks and skills, the framework is qualified as a reference in the assignment of responsibilities, as it demonstrates which tasks and which skills have a strong relationship, making it possible to demonstrate how the professional can evolve, through the proficiency levels.

Leaving the context of practitioners and migrating to the academic context, three other competency frameworks were explored, namely, IS2020 (cf. Leidig et al. [2021]) and MSIS2016 (cf. Topi et al. [2017]), promoted by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and the Association for Information Systems (AIS), and IT2017, promoted by the ACM and the IEEE Computer Society (IEEE-CS). MSIS2016 defines itself as a Global Competency Model for Graduate Degree Programs in Information Systems. The model makes an overview of the Information Systems area, arguing that business is not the only domain where IST professionals can apply their competencies, suggesting different paths for these professionals, like healthcare, government, education, and law. MSIS2016 comprises nine Information Systems (IS) competency areas, each one with their competency categories and, per se, having four different levels of competency category attainment, namely, Awareness, Novice, Supporting, and Independent. In total, there are 88 competency categories, and for each competency category, the framework provides examples of what the graduates would be able to do.

IS2020 is a similar framework to MSIS2016, but targeting undergraduate programs in IS. The framework defines competency as the combination of knowledge (the know-what), skills (the know-how) and dispositions (the know-why) in the context of performing a task. In order to express skills, IS2020 adopted Bloom’s Cognitive Levels as the basis for suggesting approaches to the application of knowledge, namely, 1-Remembering, 2-Understanding, 3-Applying, 4-Analyzing, 5-Evaluating, and 6-Creating. It also maps 11 dispositions, concerning behavior. For each competency, knowledge elements are defined and classified in terms of skill level (Bllom cognitive level), and the recommended key dispositions associated to the competency are indicated. In total, IS2020 proposes six competency realms encompassing 19 competency areas, which instantiate 178 competencies that guide the design of undergraduate programs in IS. The framework also articulates its competency areas to those of MSIS2016, showing what competencies defined in IS2020 will prepare individuals for master studies in the domain of IS. An important aspect of IS2020 is that although they recognize that there is reason to link tasks to professional activities, the authors did not provide examples of tasks. The framework follows a more conservative approach, focusing on graduates’ competencies that are acquired through studies (cf. Leidig et al. [2021]).

The other framework related to the academic context, IT2017 (cf. Sabin et al. [2017]), aims to provide guidelines for the design of higher-level courses (bachelor’s) in Information Technology (IT) It has a similar structure to that of IS2020, including the need to guide students so that they hold certain behavior-level attributes, which will enable them to apply technical-level attributes. The framework addresses the main concepts of the IT area, emphasizing undergraduate programs in that area. IT2017 defends that competency is the result of the sum of knowledge, skills and dispositions, and IT competencies are the sum of these items applied in a professional context. With a different name, IT2017 separates competencies into groups of domains, differentiating them as essential and supplemental. The essential domain group is composed of 10 subgroups, accounting for 83 domains, while the supplemental domain group is composed of nine subgroups, accounting for 69 domains. Performance goals and professional practice are captured by a set of verbs classified into the following six categories: Explain, Interpret, Apply, Demonstrate Perspective, Show Empathy, and Have Self-Knowledge. Each domain has a scope, specific competencies, and related subdomains.

In this work, eight competency frameworks were analyzed, each one composed by different concepts that make up what the authors of the frameworks define as competency. Through the proposal of a definition for the competency construct and an associated set of rules for expressing instances of the component concepts (the grammar), we hope to increase the maturity and rigor with which these matters are dealt with.

In the next subsection, we present the main concepts in the aforementioned frameworks and advance definitions that will be useful for the standardization of the application of those concepts within the scope of this study.

2.2 Main Concepts

Considering that IST was the primary focus of this work, in the beginning, we sought for concepts defined and applied specifically in IST, and the frameworks that initially contributed to the study were e-CF and SFIA, and later iCD. Considering the structure of each framework, the definitions for the concepts are contrasting. When comparing SFIA and e-CF, for example, a common concept is that of skill, however, its application is different. In e-CF, skill is one of the elements that support the existence of a competency, while in SFIA skill is related to a professional area. Also present as central to iCD, the concept of skill is referred as a group of expected functions that the professional performs. Although these frameworks, as mentioned, pertain to the area of IST, the results of the relationship between these frameworks had some commonalities with the structure of broad non-specific frameworks, such as O*NET and ROME.

According to the e-CF definition, the competency concept can be defined as a demonstrated ability to apply knowledge, skills, and attitudes for achieving observable results. In this definition, some concepts are pointed out that need special attention, such as ability, knowledge, skill, and attitude. The e-CF notes that competency is a holistic concept, being related to workplace activities, and incorporating behaviors expressed as embedded attitudes.

In what concerns IT2017, IS2020, and MSIS2016, these documents build on the concept of competency, laying out professional profiles for the IST area, defining skills, tasks, and levels of difficulty related to the functions performed by IT and IS professionals.

In this work, we consider that competency has two pillars that support it, namely ability and posture. A certain ability might be performed at different levels of proficiency, expressing the complexity of the knowledge and skill associated with that particular ability. Since the combination of knowledge and skills indicates a level of complexity for a given ability, there is also the possibility of measuring the complexity to perform a given task, making evident the relevance of the ability element in this competency structure. For each task, there may be a set of tools necessary for its execution. The other pillar that supports competency goes beyond technical factors, addressing personal factors, which are equally relevant to competency. The professional’s posture is something that can be identified through attributes and characteristics observed in the work environment, which are the dispositions that, in turn, support the occurrence of certain behaviors by the professional and that enact his/her competency. The definitions proposed for the competency construct and competency-related concepts are now presented, built upon IST and general competency frameworks, as well as entries from dictionaries:

Competency: 1It refers to a combination of abilities and postures at the individual level to solve a given task at a specific time. 2It must be related to a professional area where individuals employ their abilities.

Ability: 1It refers to the condition that indicates someone can perform a certain task, having a degree of proficiency in the use of resources, which at the individual level refers to the possession of knowledge and skills. 2It has great proximity to the definition of a position to be held by a professional.

Posture: 1Classifier of the recurrent behavior observed in the individual. 2It characterizes the moment when the individual responds to a stimulus received, influenced by his/her disposition in the face of an event, which leads to the performance of specific behaviors.

Disposition: 1It refers to an inclination or tendency to favor an alternative over other(s), which results in one or more behaviors, supporting an individual’s characteristic posture. 2It specifically addresses inclinations, individual preferences.

Behavior: 1It is what can be observed as the result of a stimulus received by the individual, depending on the environment in which he/she is located. 2It is influenced by the beliefs and experiences that the individual has and contributes to the evolution of knowledge at the individual level. 3It is the immediate response to a stimulus.

Task: 1Something that can be performed by the individual, in fulfilling a demand or attending to the solution of a problem, requiring the use of one or more abilities and one or more postures for its full fulfillment, as expected. It is possible that, for its execution, it is necessary to use one or more tools. 2It is something that can be fulfilled by employing (posture) the individual’s abilities.

Tool: 1Auxiliary technological resource that can be used to accomplish a given task. A tool can be involved in different tasks, just as a task can demand different tools for its execution. 2It is something that can be mobilized during the employment (posture) or ability as a support for the completion of a task.

Proficiency: 1It indicates the level by which the individual is trained, considering the resources possessed (knowledge and skills) and the results that can be obtained when putting them into practice (posture). 2The proficiency of an individual must indicate the result that he/she must deliver when acting professionally.

Skill: 1It is one of the elements that make up the ability of the individual and may be carried by the individual’s posture (along with knowledge). 2It refers, in some situations, to the application of knowledge acquired, and in other situations, it refers to the application of naturalknowledge, both intending to solve some demand in the professional scope. 3Some skills support the execution of other skills, that is, one skill may depend on another to be applied. It is important to emphasize that having skills is a necessary condition for the professional to be able to perform tasks.

Knowledge: 1It sustains the individual’s action in the execution of his/her skills or in the conduct of the professional position he/she holds. 2It is what can be acquired through experience and study; thus, the sources of knowledge acquisition are the practice of the individual’s abilities and the individual’s participation in training and qualification courses. 3It is considered that knowledge is improved through its practice (posture), forming the beginning or basis of an ability formation process. 4There is knowledge that supports the acquisition of another knowledge. This means that for acquiring some specific knowledge it may be necessary the existence of some previous knowledge.

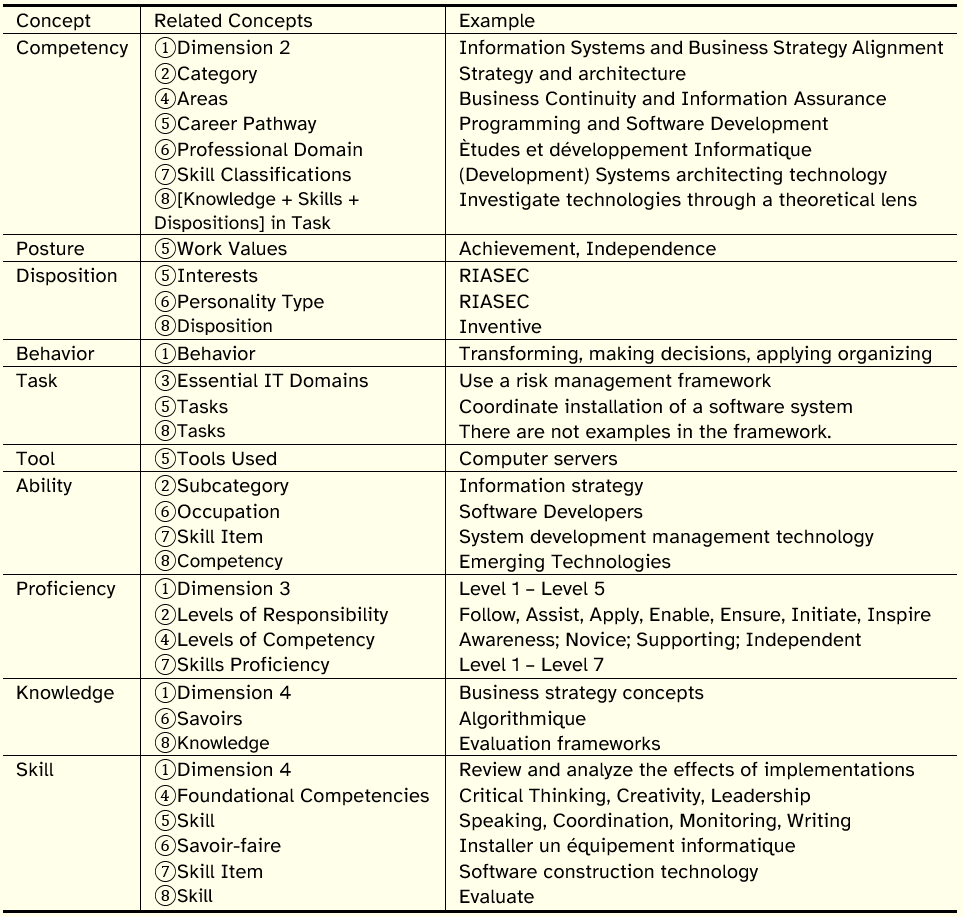

Table 1 covers the concepts, the framework to which they referred to, and how the concept was addressed in that framework. Frameworks are signaled by numbers, identified as ①e-CF, ②SFIA, ③IT2017, ④MSIS2016, ⑤O*NET, ⑥ROME, ⑦iCD, and ⑧IS2020. Analyzing the provisions in Table 1, although we have equivalent examples related to the same concept, having different sources, we note the absence of criteria for its writing. Setting up criteria for writing the attributes that make up the competency construct can provide some advantages, such as classifying the element according to the concept, establishing dependencies between competency attributes, indicating an evolutionary path for the professional, and raising the maturity of a particular professional area.

Table 1: Concepts and Their Relationships with Framework

Considering what has been portrayed regarding the difficulties involved in investigating the subject of competency, and avoiding being limited to an isolated research initiative, a step to standardize the application of competency in future studies on the subject is suggested in this work. This possibility concerns the use of BNF as a means for the definition of writing standards for the concepts related to the competency construct, such as those present in this subsection, considering their definitions and correspondence with reviewed frameworks. Next, we provide a brief overview of BNF.

2.3 Backus-Naur Form

BNF is one of the most used methods for writing syntax for context-free grammars [McCracken and Reilly 2003]. The origin of the name comes from the creators of BNF, John Backus and Peter Naur. The first incarnation of BNF was used to describe the syntax of the programming language ALGOL 60, in 1960. In the following years, updates to the BNF notation were made.

In this proposal, we will use BNF, because we believe is the form that allows a better understanding of the writing patterns, even for non-IST professionals. According to Sebesta [2011], there are three advantages when opting for the use of BNF: clarity and conciseness of the BNF description; the possibility to use BNF as a basis for a parser; and the BNF-based implementations being relatively easy to maintain due to their modularity.

From a standardization point of view, it is desirable that meta-syntaxes, such as BNF and its variants, possess a set of characteristics [ISO 1996], like: conciseness, precision, formality, naturality, generality, simplicity, self-describing, and linearity. In practical terms, considering BNF as a standard for writing, we can define transparent delimitations and rules that mitigate the mishmash associated with definitions of competency.

To write a grammar in BNF, one uses the set of symbols from the BNF notation. The symbols needed to understand the competency grammar that will be presented in the next section are now addressed.

<text> = <capital> | <tiny>

3. Competency Grammar

In view of the scenario described for the concept of competency, we propose a BNF grammar that establishes the syntactic rules for writing competencies, as well as the elements that make up its structure, according to the semantics conveyed in the definitions of the concepts. These rules aim to prevent the undisciplined use of competency related concepts, by reducing the variations in the application of these elements and, therefore, heading towards a more mature state in approaching the competency construct. For each component of the construct, a syntax with specific rules for its writing is proposed, so that to maintain and strengthen the writing pattern proposed.

Code 1: Syntactic Structure of Competency Grammar

<competency> = <expr>

<posture> = <adjective>

<disposition> = <action verb>

<behavior> = <action verb> + <expr>

<ability> = <expr>

<task> = <action verb> + <expr>

<tool> = <expr>

<skill> = <expr>

<knowledge> = <substantive> + <expr>

<expr> = <part> | <expr> + <part>

<part> = <substantive> | <preposition> | <article>

<adjective> = TEXT

<action verb> = TEXT

<substantive> = TEXT

<preposition> = TEXT

<article> = TEXT

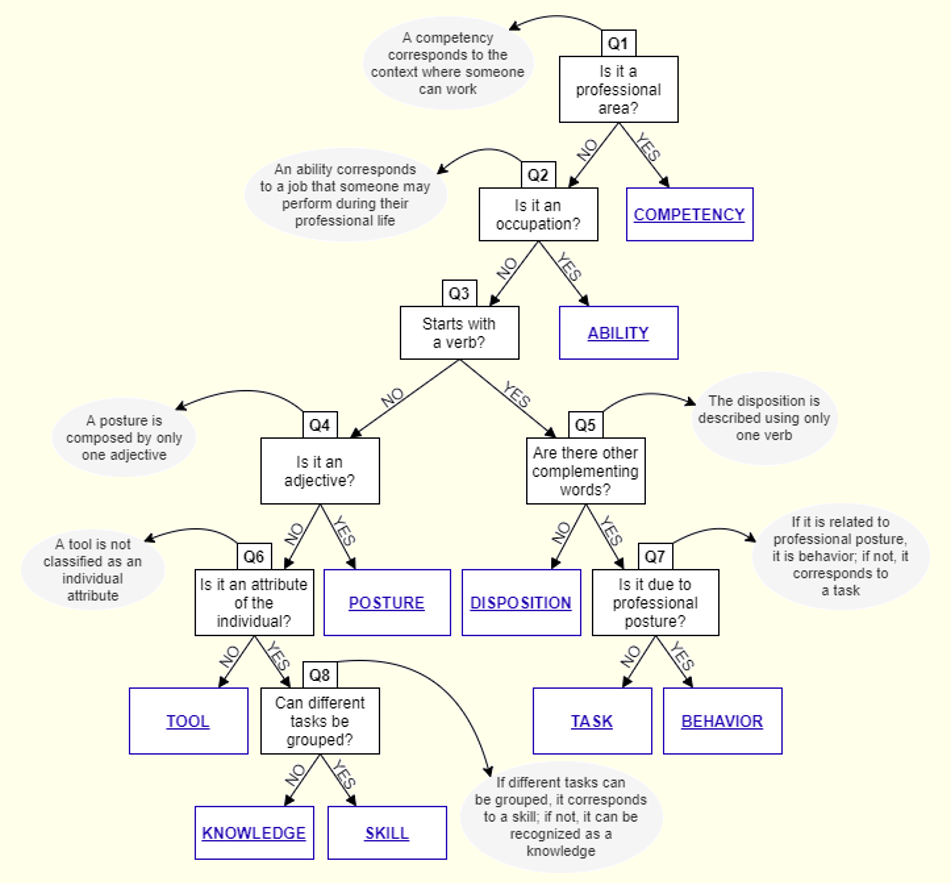

Figure 1: Decision Tree to Concepts Classification

When using this instrument to support the classification of a sentence or word that is related to the context of a profession, it is expected that the user will be able to classify it in one of the concepts covered by the competency construct, bearing in mind the definition proposed for the concepts. Afterwards, the sentence formulating the professional attribute must be written according to the proposed BNF grammar.

4. Validating the Competency Gramar

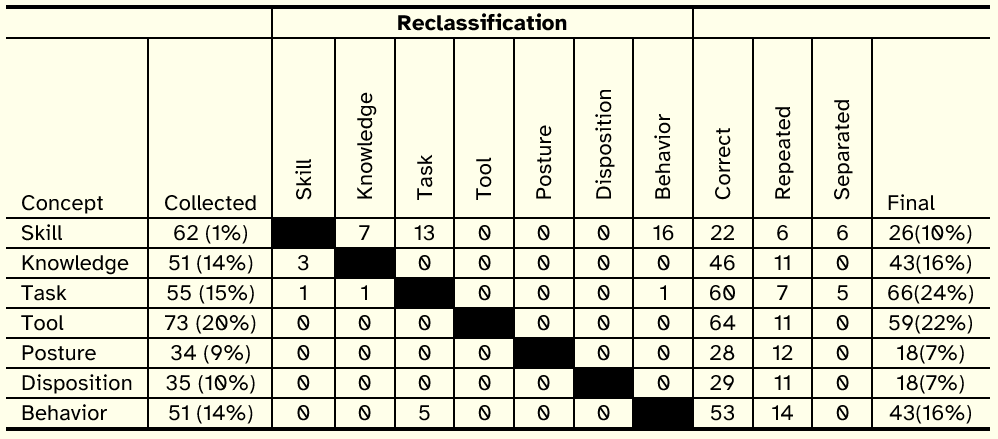

Table 2: Synthesis of Collected Data

Respondents received a spreadsheet, with each tab of the spreadsheet referring to a concept presented in Table 2. For each concept presented, its definition was also available, as well as the rule for its writing. Each respondent had available eight attributes written according to the proposal, for each concept, and they were asked to include five to ten attributes that corresponded to their professional attribution, referring to their work routine, also for each concept. Each one had assistance available whenever required, and the deadline for returning the completed worksheet was seven days. The spreadsheet also had a tab that presented a compilation of the data entered by the respondents in all tabs, so that an integrated view of their contribution to their profession was possible.

Considering that the study also looked at frameworks related to other areas of professional activity, the opportunity to test the rules and standards in different areas was seized. Thus, five professionals from other professional areas (Biology, Human Resource Management, Psychology, and Veterinarian) performed the procedure of filling out the forms with attributes inherent to their current professional occupations. Afterwards, a process for the collection, analysis, and validation of data similar to the one applied to IST professionals was conducted. In the end, 184 attributes were obtained, properly classified in the concepts addressed in this work. This effort was justified by the intention to generalize the study to other areas of professional practice, since the proposed grammar is not intended to be limited to classifying competency attributes only for the IST area, but to offer support for any professional area.

5. Conclusion

In an attempt to standardize the approach to the notion of competency and related concepts, some challenges were faced. These challenges, for the most part, are related to the perceived low rigor in the application of the concepts. Hence, in the initial phase of this study, adjustments in the definition of the concepts were made by the authors, in an attempt to clarify and support the differentiation of professional attributes among the range of concepts involved.

There is a variety of frameworks related to the theme of competency, specifically focused on IST, which organize professional attributes. This variety may be related to the pace of growth of the IST area, where a myriad of different activity sectors employs IST professionals. Since IST play an important role in all professional areas that require information processing of any nature, IST professionals are required to operate in diverse environments. This gives rise to a number of IST job specificities, according to particular contexts of activity, such as health, logistics, education, government, and business. The pervasiveness of the IST profession and the need to broaden the perspective on competency justified the analysis of general competency frameworks to find out their approach to the topic of competency, in comparison to the IST frameworks.

However, it is necessary to consider the limitations of this work. One refers to the number of participating professionals. Our test sample involved a small group of professionals, and we strongly believe that extending the process to IST professionals with different abilities, as well as to professionals from other areas besides IST (an effort for which the first steps were taken in this study), in future works would put the grammar to a stress test, eventually revealing the need for adjustments in the rules of the grammar. A second limitation regards the type of individuals that participated in this study. Besides IST professionals, it also makes sense to involve IST recruiters and IST leaders to validate the professional attributes informed by the respondents, making this inquiry a new phase of the grammar validation process. Along the same line, the participation of IST educators and trainers would provide further indications on the validity and usefulness of the grammar. Although laborious, these are essential steps for the refinement of the competency grammar and for increasing the confidence in its practical application.

To improve and supplement the data on IST competencies, structured according to the competency construct and formulate observing the competency grammar, more work is required. Besides enhancing the characterization of the IST competencies versed in this work, there is a need to start collecting and organizing attributes pertaining to other IST competencies. After reaching a certain level of maturity in the description of an IST competency, or even in an ability, it becomes possible to move on to the next stage. This stage would involve the definition of the degree of difficulty of the ability, mapping it to the levels of proficiency proposed in this study, as well as pointing out dependencies between professional attributes. To this end, it is deemed necessary to engage professionals, both to define the degree of difficulty and to point out the dependencies. This work would provide guidance of great relevance for professionals who wish to evolve in their careers.

The generalization of this proposal is envisaged as a future endeavor. The idea is to involve researchers from different professional areas to collaborate in the data collection, analysis, and validation of the process for defining competency profiles, using the same set of rules–the competency grammar–presented in this work.

References

APA Dictionary (2018). Competence. Available at: http://dictionary.apa.org/competence

Cambridge (2020). Competency. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/pt/dicionario/ingles/competency

Collins Dictionary (2017). Competence. Available at: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/competence

Department of Labor (2020). O*NET OnLine. Available at: https://www.onetonline.org

ETALAB (2020). Répertoire Opérationnel des Métiers et des Emplois (ROME)—data.gouv.fr. Available at: https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/repertoire-operationnel-des-metiers-et-des-emplois-rome

European Union (2016). European e-Competence Framework 3.0. Available at: http://ecompetences.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/User-guide-for-the-application-of-the-e-CF-3.0_CEN_CWA_16234-2_2014.pdf

Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital Competence in Practice: An Analysis of Frameworks.

Hayashiguchi, E., O. Endou and J. Impagliazzo (2018). The Proceedings of EDUNINE 2018—2nd IEEE World Engineering Education Conference: The Role of Professional Associations in Contemporaneous Engineer Careers, 1–6.“ Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices : a theory of vocational personalities and work environments, third edition. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

ISO (1996). ISO/IEC 14977:1996—Information technology—Syntactic metalanguage 000 Extended BNF. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/26153.html (Accessed: 13 January 2020).

Janssen, J., S. Stoyanov, A. Ferrari, Y. Punie, K. Pannekeet and P. Sloep (2013). Experts’ views on digital competence: Commonalities and differences. Computers & Education 68, 473–481.

Leidig, P., H. Salmela, G. Naderson, J. Babb, C. de Villiers, L. Gardner, J. F. Nunamaker, B. Scholtz, V. Shankararaman, R. Sooriamurthi and M. Thouin (2021). IS2020: A Competency Model for Undergraduate Programs in Information Systems. Association for Computing Machinery and Association for Information Systems.

Oberländer, M., A. Beinicke and T. Bipp (2020). Digital competencies: A review of the literature and applications in the workplace. Computers & Education 146.

Oxford (2014). Competency. Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/competency

Sabin, M., H. Alrumaih, J. Impagliazzo, B. Lunt, M. Zhang, B. Byers, W. Newhouse, B. Paterson, S. Peltsverger, C. Tang, G. van der Veer and B. Viola(2017). Information Technology Curricula 2017—IT2017: Curriculum Guidelines for Baccalaureate Degree Programs in Information Technology. Association for Computing Machinery and IEEE Computer Society.

Sebesta, R. W. (2011). Conceitos de Linguagens de Programação, 9 edição. Porto Alegre: Bookman.

SFIA Foundation (2021). SFIA 8—- The complete reference guide. Available at: http://www.sfia-online.org/en

Topi, H., S. A. Brown, B. Donnellan, B. C. Y. Tan, H. Karsten, J. Á. Carvalho, J. Shen and M. F. Thouin (2017). MSIS 2016: Global Competency Model for Graduate Degree Programs in Information Systems. Association for Computing Machinery and Association for Information Systems.