Original source publication: de Moura, F. L. and F. de Sá-Soares (2020). A Generic Proposal for Competence Mapping: A Case Study from Information Systems Discipline. Proceedings of IBIMA2020—The 35th International Business Information Management Association Conference, Seville (Spain).

The final publication is available here.

A Generic Proposal for Competence Mapping: A Case Study from Information Systems Discipline

Centro ALGORITMI, University of Minho, Portugal

Abstract

The competence literature uses a set of terms whose definitions have a high degree of ambiguity and intersection. This situation causes difficulties when applying competence frameworks for describing the content of jobs and planning the evolution of competences, both at an individual and organizational level. This work focuses on the competence construct, reviewing related concepts and identifying relationships between them. The authors provide a structure for the competence construct, which integrates and articulates the concepts of knowledge, skill, ability, capacity, posture, disposition and behaviour. The structure support the proposal of a mechanism for mapping the internal competences of an organization. The mapping may assist the organization to compare its current set of competences with the desired competence blueprint. Underlying this mechanism is the assumption that individuals working in an organizational environment are the source of competences for the organization. The mechanism may also assist an individual to set a course for professional development. To illustrate the application of the mapping mechanism a scenario informed by an Information Systems and Technology framework is used.

Keywords: Competence; Information Systems; Information Systems and Technology Competences; Competence Mapping

Introduction

The central theme in this paper—competence—has been the subject of many scientific discussions and investigations. However, despite the number of works that have been published (exceeding 8,000 in 2019 according to the Web Science and more than 14,000 based on Scopus), additional research is required, as some concepts related to competence are considered synonyms by some authors or overlap in their meanings in the view of others. The existing mix of conflicting views may raise doubts regarding the approaches adopted by works on professional competences. To mitigate the drawbacks of that situation, this study promoted searches and analysis in several dictionaries and frameworks in order to better organize concepts and, subsequently, to identify relationships between them and influences they exert on each other. The starting point of the study were several competence frameworks, lately complemented by the analysis of additional references and dictionaries.

The literature review suggested an absence of criteria to make sense of the terms associated to competence, hindering the development of a conceptual structure capable of defining a profession. This state of affairs was recognized in spite of the existence of explanations for the meanings of career, function, job, work, and even profession. The absence of criteria may also interfere with the design of training programs or graduate and postgraduate programs, as these programs need to focus on learning objectives that take into account the professional profile required by the labour market. Hence, we argue for the need of conducting research studies on competence-related concepts and on their relationships.

In order to produce a structure for the competence construct, we compared, grouped and contrasted the definitions of related concepts found in the literature reviewed. Then, we advanced revised definitions for the concepts so there was no overlapping and incompatibility in the proposed structure for the competence construct. This made possible a visual display to show how concepts relate and to trace the path an individual may take to evolve in his/her professional field.

Building on the structure for the competence construct, in this paper we propose a mechanism for mapping competences. This mechanism assists in diagnosing existing competences, suggesting paths to develop individual competences and defining requirements to meet organization’s competence demands.

Following this introduction, we briefly describe competence frameworks. These frameworks include various concepts present in the proposed mechanism for competence mapping. In the subsequent section we present definitions for the concepts, based on competence frameworks and other references, such as scientific articles and dictionaries. The section includes a display of how the concepts relate at an individual level of analysis. The next section presents a competence measurement mechanism and shows how it can be used to map an organization’s competences. Afterwards, representations are provided to exemplify some applications of the mechanism, based on a scenario, for both measurement and mapping purposes. For the sake of illustration, the example provided uses a framework from the Information Systems and Technology (IST) domain. The proposed mechanism allows the use of other frameworks for the purpose of competence measurement that the user of the mechanism (an individual, a group or an organization) considers appropriate. In the final sections of the paper, the authors draw conclusions and propose future work.

Competence Frameworks

Different competence-based approaches have been developed, serving as guidance in diverse professional areas. A well-known framework is the European Competence Framework (ECF), which in 2016 was recognized as a European Standard, aiming to standardize an approach to competences, skills, knowledge and proficiency levels [European Union 2016], for the IST area, and providing descriptions for typical professional role profiles. Its architecture divides competence into four dimensions. Dimension 1 refers to the purpose of the competence. Dimension 2 includes the name and a generic description for the competence. Dimension 3 covers proficiency levels for the competence and its equivalence with the European Qualification Framework (EQF). Dimension 4 covers two fundamental concepts for competence, namely knowledge and skill. The framework includes examples of skills and knowledge for each competence, although recognizing that competence is not limited to the examples provided and may involve other skills and knowledge not mentioned in the framework.

In addition to the ECF, there are other frameworks that aim to standardize the approach of competences, such as the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA) [SFIA Foundation 2015, 2018] and the i-Competency Dictionary (i-CD) [Hayashiguchi et al. 2018], both in the IST ares. SFIA divides Skills into categories and subcategories, with each skill having specific levels of responsibility, which include descriptions about the practical application of the skill. Focusing on skills, i-CD provides more than 2,200 task items and 10,000 knowledge items.

Other frameworks are transversal to professional areas of activities. The framework used in the United States of America, O*NET [National Center for O*NET 2008], represents an approach to competences, in which the professional occupations that an individual may have during his/her active professional life are the central theme. Another approach focusing attention on the scope of job specificities and proficiencies is ROME [ETALAB 2020], maintained by the French government. This framework covers synonyms for jobs, i.e., occupations that have different names, but that in practice are equivalent. Similar approaches are found in other countries. For example, the Brazilian Catalogue of Occupations (CBO) provides an extremely simplified structure, targeting the profession/occupation that an individual will perform, classified in a base group, which, per se, belongs to a subgroup. The CBO, as well as the Portuguese Catalogue of Professions (CPP), pay attention to the profession, offering no support that indicates the path an individual may follow to reach that position.

These frameworks, as well as several dictionaries, do not always attribute the same meaning to the concepts addressed and, although they do not enter into irremediable disagreement, there is a need for more attention in the application of the concepts, at least to prevent an uncritical and generic use. Hence, taking into account the different approaches adopted by each framework, it is advisable to highlight the specificities associated to each concept employed in this work–Competence, Ability, Proficiency, Skill, Knowledge, Posture, Disposition and Behaviour–and to advance revised definitions for each of them.

Main Concepts

Frameworks such as O*NET, ROME, CBO and CPP do not directly portray the term competence, but refer, as a central theme, to occupation or profession, containing descriptions that complement the ECF’s approach, having competences as the central theme. SFIA places skill as a central theme and considers the levels of responsibility as the specifics of the skill, which are grouped into categories and subcategories.

The i-CD uses the concept of competence as a central theme and considers that its origin is placed in the human resource, which is the source of the organization’s capability since it provides the needed competence for the business execution. Fleury and Fleury [2001] corroborate this view, indicating that competence refers to the stock of resources that the individual holds. However, McClelland [1973] draws attention to the fact that competence can be observed in the performance of a position exercised by the individual, provided that the individual has skills, knowledge, behaviors, attitude, ability and necessary dispositions corresponding to the individual’s professional occupation. Nordhaug and Gr⊘nhaug [1994] advocate that the elements that make up competence are knowledge, skill, and ability related to the work performed by the person. The work of these authors provides important support for the definition proposed in this study for the concept of competence.

Looking to the ECF framework, it makes sense to say that competence relates to a professional area where individuals employ their abilities, such as Programming and Software Development, Network Systems, Quality Assurance, among others. The proposed definition of ability by the Cambridge Dictionary [Cambridge 2020a] indicates ability as an occurrence that enables someone to be able to do something, supported by the Oxford Dictionary that complements the explanation of the concept, referring to ability as the capacity to do something, physically, mentally, legally, morally, etc. [Oxford 2020a].

Taking into account these delineations, we define competence as a combination of the individual’s abilities and postures to attend to a certain task at a specific moment. The definition emphasizes the temporality of the occurrence of the competence, as it is not something permanent or static, but an event that occurs at the right time and involving appropriate people to accomplish a task.

Among the cited frameworks, only O*NET mentions the concept of abilities. However, its context of use does not match the one addressed in this paper. This is justified by the fact that the authors of the present work consider that competences have different specificities. For example, in a particular area of professional activity it is possible for different professionals to work together and collaborate in a project, with the specificities of competence being responsible for different groups of tasks. In the case of ECF, which articulates skills, knowledge, and attitudes as elements of competence, the specificity of competences is taken into account and reflected in the level of abilities. ECF establishes a relationship between the concepts of knowledge and skills, so that different combinations of knowledge and skills imply varying levels of proficiency related to ability in the context of a competence.

In what concerns abilities in O*NET, the framework treats it as the natural resources of the individual. However, the authors of this paper consider the need to separate what is natural from what is acquired. Abilities have a broader view and include natural resources, which are defined as aptitude, being a factor that influences positively or negatively on the variables that indicate the level of abilities of the individual, corresponding to the natural talent possessed by the professional. The APA Dictionary [APA 2018] defines aptitude as a potential in a particular area, while the Cambridge Dictionary [Cambridge 2020b] refers to a natural skill or ability. In addition to the facility in some aptitude or some ability, the Business Dictionary [Business Dictionary 2020] complements by indicating that the individual’s interest in some task or responsibility is also a factor that will influence professional performance when putting his/her ability into practice, which will also enable the occurrence of fitness improvements resultant from practice. Therefore, practice is one of the ways to improve competence, that is, it refers to the possibility of someone doing a task in a more efficient way than he/she already does, through experience. The other way to improve competence is to look for training or qualifications that promote professional development, whether through the acquisition of knowledge or the practice of new skills.

Knowledge, considered here as one of the ways that leads to obtaining abilities, is what can be acquired through training courses and education, which, according to IT2017 [IT2017 2017], must appear in the official documents of the training programs. In the context of EQF [European Communities 2008], knowledge is referred to as the result of the assimilation of information through learning, which may come from facts, principles, theories, and practices that are related to a field of work or study. Grant [1996] emphasizes that the creation of knowledge is an individual activity and that knowledge is the primary source of value and may be the factor that will differentiate one organization from another, due to the amount of knowledge it might have. Takeuchi and Shibata [2006] emphasize the division of knowledge into two categories, corresponding to tacit and explicit. They refer to the knowledge that can be expressed in words or numbers and that can be shared as explicit knowledge. However, the authors refer to the existence of knowledge that cannot be easily perceived and expressed, called tacit knowledge. This category of knowledge is deeply rooted in an individual’s actions and experiences, as well as in its ideals, beliefs, values or emotions.

Another way to support and acquire the ability at the individual level is the skill of the individual. The skill is the knowledge put into practice, considering the possession of the means for such an occurrence. The EQF refers to the skill as the possession of the means to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems [European Communities 2008].

What sustains the relationship between stimulus and response is the disposition of the professional, considered as an exclusive inclination or tendency of the individual [Oxford 2020b] to choose an alternative over others, basically supported by individual preferences [Strickland 2001]. The result, therefore, is the behaviour, conditioned to the environment in which it is located. According to Fonseca [2016], the behaviour is directly influenced by experience, and Peppard and Ward [2004] note that the behaviour of the individual is the result of organizational demands, social demands, and personal demands.

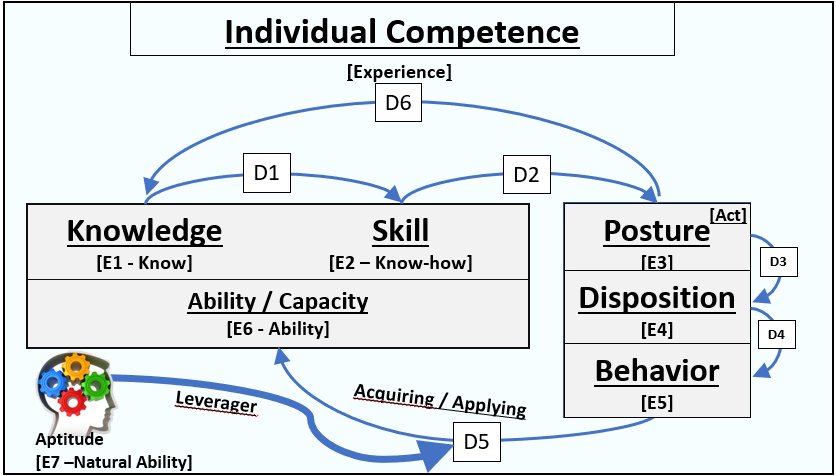

Figure 1 represents the relationships between concepts related to the construct individual competence.

Figure 1: Relationship between Concepts related to Individual Knowledge

Through Figure 1, it is possible to see that the competence construct, at the individual level, is supported by two main concepts, which are the practitioner’s ability [E6] and posture [E3]. The formation of the ability occurs through the combination of knowledge [E1] and skill [E2], and this formation allows even greater possibility to measure the ability and indicate their different levels of proficiency. The posture is dependent on the existence of disposition [E4], which will lead the person to perform different behaviors [E5]. Professional ability can be more easily practiced or improved when there is an individual’s aptitude, which is considered a natural ability for an area of professional activity. The arrows in the picture indicate the points where there is a relationship between the concepts, when one considers the dependencies between them, being:

D1: Dependence of skills related to the acquisition of knowledge;

D2: After the possession of the means to perform an action, there is a dependence on the professional posture to effective action;

D3: Dependence on the disposition so that the posture is maintained by the professional;

D4: Behaviors that will result from the disposition;

D5: The behavior of the individual leads to the acquisition of new abilities or leads to the application of abilities already possessed;

D6: Considering knowledge as the basis of skills, there is the possibility of being improved precisely through professional posture and behavior arising from the posture. The fact that occurred at this moment is the acquisition of experience, which influences the attitude of the professional.

Although the relationship between the concepts is clarified in Figure 1, it must be acknowledge that an organization is formed by different people with different backgrounds and experiences. In the next section, it will be discussed the proposal of a generic mechanism that enables the mapping and identification of competences and the indication of a path for improvement, according to measures defined by the organization itself.

Proposal of a Measurement Mechanism

An organization is made up of people, who, at their different hierarchical levels, will have different experiences, although the professional path followed by some individuals may be equivalent. The training may be similar, as well as the professional experiences, but the way of interpreting them will be unique, referring to the beliefs and inclinations hold by the professional, which influence its behavior for the application of its ability.

Considering the different professional profiles present in the organizational environment, it is relevant to monitor the resources that the organization has, which may provide support to identify possibilities for improvement and situations in which the organization’s potential is being underutilized. It is also possible to define internal action plans, like offer of seminars, workshops, training, reformulation of the team regarding the projects in execution, to meet gaps related to the identified needs.

Figure 2 is a representation that has eight different points of analysis, related to the concepts covered in the previous section. It is arranged in a way that makes it possible to position the organization at a specific point that corresponds to the relationship proposed, contemplating the training of professionals and their experience in their area of professional activity. This relationship is a proposal that addresses two parameters but that does not define measurement scales. The definition of measures for the parameters should be defined by the organization, eventually by making use of external references, such as widely used competence frameworks or specific references for some area of knowledge. In any case, a document that can assist in the definition of the measurement scale can be the plan of the organization, considering that it contemplates the area of human resources and is in communication with the other sectors of the organization, which will present the demands related to the professionals necessary for the continuity of the organization.

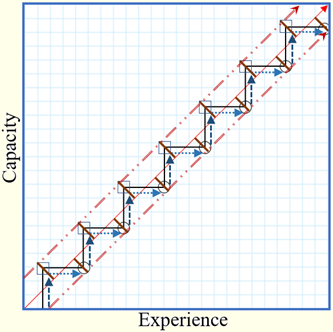

Figure 2: Evolution of Competence

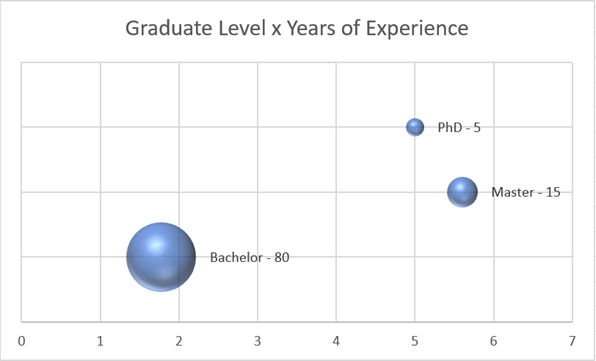

To facilitate the understanding of the representation in Figure 2, Table 1 provides a legend for the symbols used in the picture.

Table 1: Representations about Competence Evolution

The first sign, corresponding to (1), represents how competence should evolve. According to the example, the evolution of a professional is measured in terms of experience and capacity, corresponding to the training of the organization’s professionals. The second sign (2) is the influence of the natural talent, which serves as a facilitator for the evolution of the level of ability. In the representation of phases, the evolution of competence is based on two variables, one vertically and the other horizontally. The vertical renders the moment when knowledge and skills are acquired (3), either through internal training, hiring employees, etc., while the horizontal reflects the moment when the acquired knowledge and skill are placed in practice (4) and experience is gained, serving as an influence on the evolution of ability. The sign equivalent to (5) represents the moments when there is an expansion of the ability, motivated by participation in training or qualifications that meet the metrics defined by the organization. In the sequence, (6) corresponds to the improvement of the results in the context of professional practice, that is, what the professional can do considering his/her ability. The evolution of ability occurs through the posture of the professional, which leads to the acquisition of knowledge and skill, as well as when faced with a specific scenario, he/she sees the opportunity to apply the ability he/she possesses, being represented by (7), which is the line that is directly related to all the elements of the representation. The (8) corresponds to the limitations that a professional may have when exercising his profession, depending on the level of proficiency of his ability.

The Mechanism in Practice

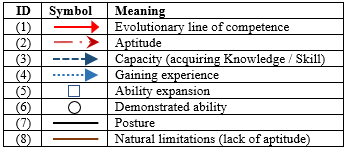

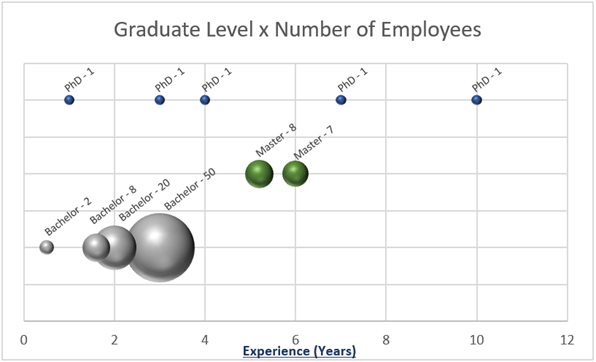

In order to illustrate the application of the mechanism, the following scenario is considered: An organization has 100 employees, 80 of which have an undergraduate degree, 15 have a master’s degree and 5 have a PhD degree. The average time of experience of the Bachelors is 1 year and 8 months, while the Masters have 5 years and 7 months of experience and the PhDs have an average of 5 years of experience. Using the proposed mechanism to perform the organization’s competences mapping, the result would be as shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 also uses the proposed mechanism; however, it presents greater refinement, referring to the existence of groups of professionals with equivalent values. This representation indicates the existence of different profiles in the staff. To this end, the proposal allows the definition of action plans, to meet the organization’s objectives of seeking to level the abilities and experiences of its employees.

Figure 3: Competence Mapping

Thus, using the concept related to the evolutionary line of competence, proposed in this work, it is supposed that the organization seeks professionals who have more experience in their area of expertise, making possible the leveraging of its employees’ competence.

Figure 4: Group of Competences

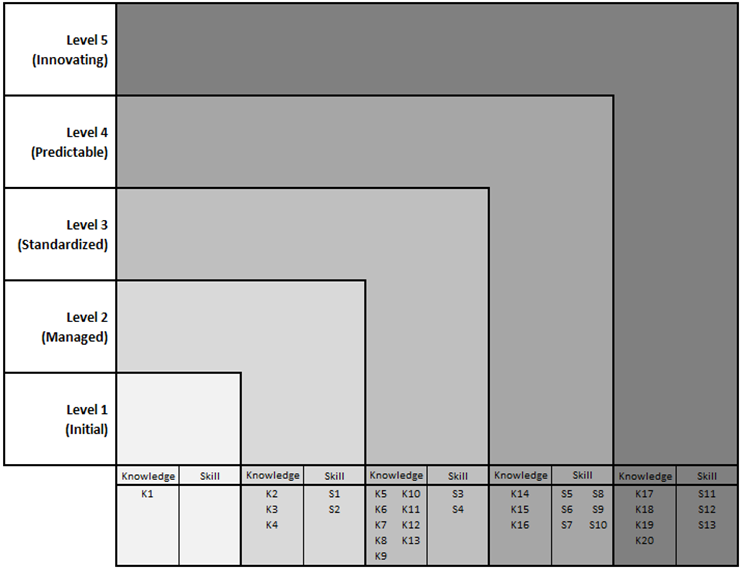

The scope of the proposed mechanism is illustrated in Figure 5. This representation involves the application of the Business Process Maturity Model (BPMM), proposed by the Object Management Group (OMG) (Object Management Group 2008]. The OMG considers that the adoption of a maturity model provides a way to implement vital practices in one or more domains of the organizational process. This model consists of five levels, which evolve from an organization that has no maturity in the process, with an inconsistent or ad hoc process and results that are difficult to predict, to an innovative, proactive organization.

Figure 5: Competence Mapping for Maturity Levels—BPMM

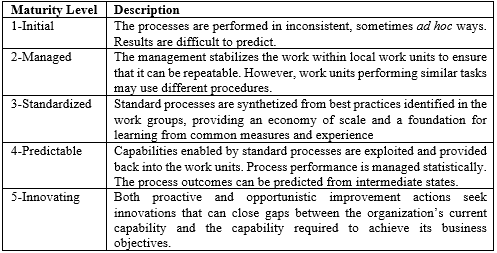

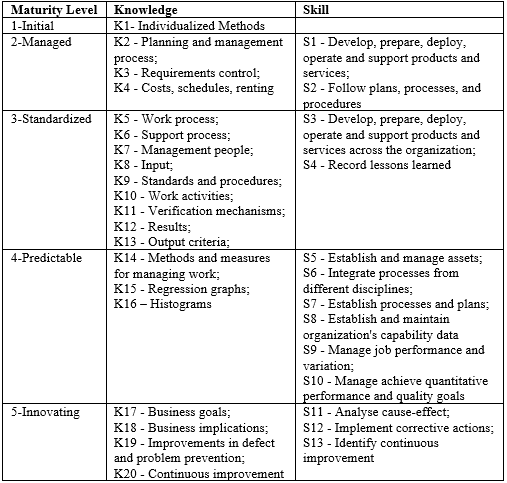

Table 2 represents the maturity levels of the model proposed by OMG, with the respective description of the scenario and Table 3 contains the Knowledge and Skills corresponding to each maturity level.

Table 2: Maturity Levels—BPMM [Object Management Group 2008]

Table 3: Knowledge & Skills for each Maturity Level of BPMM

Through this representation, following the example of using a maturity model with a relevant contribution for professionals in the IST area, it is possible to align it with managers in decision-making processes that involve the context of available human resources.

In a punctual analysis, the professional can also make use of this mechanism by him/herself. Considering that the professional holds a set of knowledge and skills, these can be put to the test at some point of its professional career, for example, to get a certification. To this end, the mechanism proposed for the mapping of competences may define, in the vertical axis of attitude (7), the values corresponding to the metrics that will be required for getting the certification, as well as depicting, in the horizontal axis of attitude (7), the length of professional experience working in a given position.

The scope of the proposed mechanism, based on the relationship between the concepts related to competence, allows its application in different scenarios since the measures can be defined by the user of the mechanism who, after mapping, may resort to the guidance provided by the concepts covered in this work.

Conclusions

During the study of the concepts coved in this work, it was found that measuring competences was also noted as being difficult. Thus, the search for a mechanism that would assist in the mapping of competences began to be defined, emphasizing the importance of meeting different demands, be at an individual or organizational level. Parameters used to measure will certainly be different from one organization to another, as demands are different, as well as the specifics of any given environment. At the individual level, the proposed mechanism also makes it possible to define measures in a generic way, since a professional should be able to identify the appropriate measurement units by using some reference or benchmark in its professional field.

Although the aim of this study is comprehensive and not restricted to particular contexts, exhaustive application of the mechanism is necessary, both as a diagnosis tool and as a tool for monitoring and following up competences and to prove its effectiveness in supporting decisions related to competences.

Future Work

In addition to the definition of a mechanism for managing and monitoring competences, the central theme of this study requires greater attention in situations involving the relationship among competences at different levels of the organizational hierarchy, such as on the individual, group, and organization level. Further studies could focus on portraying the interaction among those levels and finding out how to achieve mutual benefits for improving global competences of organization. In view of the existence of incongruences between the frameworks that used the concepts related to competences, we suggest carrying out work aiming at specifying the components of competences in specific contexts of professional practice and thus contributing to minimize certain misunderstandings, perhaps caused by the lack of criteria for defining those concepts.

Considering the concepts covered in this paper and their relationships, an additional research goal is to develop a set of rules for classifying items related to the competence construct that are currently being used in an ad hoc manner, strengthening the scientific research on competences. The purpose of this planned work is to make it possible to pay attention to problems instead of, for example, paying attention to the framework of a profession and the composition of its elements. It is our belief that communication between practitioners and academics will facilitate the structuring of professional careers. Academic institutions would also benefit, insofar as they can better understand the relationship between companies’ needs for professionals and training requirements.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia within the R&D Units Project Scope: UIDB/00319/2020

References

APA (2020). Attitude. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: https://dictionary.apa.org/attitude

Business Dictionary (2020). Aptitude. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: https://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/aptitude.html

Cambridge (2020a). Ability. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/pt/dicionario/ingles-portugues/ability

Cambridge (2020b). Aptitude. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/ptdicionario/ingles-portugues/aptitude

Collins Dictionary (2020). Attitude. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/attitude

European Communities (2008). The European Qualifications Framework for Lifelong Learning (EQF). European Communities, Brussels.

Fleury, M. T. K. and A. Fleury (2001). Construindo o conceito de competência. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 5(spe), 183–196.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal 17(2), 109–122.

Hayashiguchi, E., O. Endou and J. Impagliazzo (2018). The Proceedings of EDUNINE 2018—2nd IEEE World Engineering Education Conference: The Role of Professional Associations in Contemporaneous Engineer Careers, 1–6.“ IT2017 (2017). Information Technology Curricula 2017: Curriculum Guidelines for Baccalaureate Degree Programs in Information Technology/ Association for Computing Machinery.

McClelland, D. C. (1973). Testing for competence rather than for American Psychologist 28(1), 1–14.“ National Center for O*NET (2008). The O*NET Content Model, Detailed outline with description.

Nordhaug, O and K. Gr⊘nhaug (1994). Competences as resources in firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 5(1), 89–106.

Object Management Group (2008). Business Process Maturity Model (BPMM).

Oxford (2020a). Ability. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: http://www.lexico.com/definitions/ability

Oxford (2020b). Disposition. [Online], [Retrieved January 27, 2020]. Available: http://www.lexico.com/definitions/disposition

Peppard, J. and J. Ward (2004). Beyond strategic information systems: towards an IS capability. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 13(2), 167–194.

SFIA Foundation (2015). Skills Framework for the Information Age 6 (SFIA 6)—The complete reference guide.

SFIA Foundation (2018). Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA 7)—The complete reference.

Strickland, B. (2001). The GALE Encyclopedia of Psychology, second edition. Gale Group, Farmington Hills.

Takeuchi, H. and T. Shibata (2006). Japan: Moving Toward a More Advanced Knowledge Economy. The World Bank, Washington D. C.