Original source publication: da Costa, F. and F. de Sá-Soares (2017). Authenticity Challenges of Wearable Technologies. In Marrington, A., D. Kerr and J. Gammack (Eds.), Managing Security Issues and the Hidden Dangers of Wearable Technologies, 98–130, Hershey: IGI Global.

The final publication is available here.

Authenticity Challenges of Wearable Technologies

University of Minho, Portugal

Abstract

In this chapter the security challenges raised by wearable technologies concerning the authenticity of information and subjects are discussed. Following a conceptualization of the capabilities of wearable technology, an authenticity analysis framework for wearable devices is presented. This framework includes graphic classification classes of authenticity risks in wearable devices that are expected to improve the awareness of users on the risks of using those devices, so that they can moderate their behaviors and take into account the inclusion of controls aimed to protect authenticity. Building on the results of the application of the framework to a list of wearable devices, a solution is presented to mitigate the risk for authenticity based on digital signatures.

Introduction

For a long time information security management has been based on the CIA triad, the acronym denoting the principles1 of Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability. Over time, the sufficiency and appropriateness of these three cornerstone principles of information security have been challenged by several authors. In 1998, Parker complemented them with three new principles, namely Ownership, Authenticity, and Utility [Parker 1998]. The arrival of the new millennium with the need for organizations to adopt more agile and flat structures led Dhillon and Backhouse [2000] to argue for the inclusion of four people-related principles, known under the RITE acronym, meaning Responsibility, Integrity, Trust, and Ethicality. More recently, Teixeira and de Sá-Soares [2013] proposed a revised framework composed of thirteen information security principles and five sub-principles.

In a sense, these sets of information security principles convey worldviews concerning the theory and practice of information security. But new technology may alter our worldviews. An illustrative case is the emergence and evolution of wearable technologies and mobile computing devices offering us true information systems in our pocket, on our wrist, or through our glasses. These technologies are being equipped with ever-stronger information acquisition, storage, processing, display, and communication capabilities. By adopting and using wearable technologies in our daily activities, we are on the verge of a revolution that brings the potential to change the way we live, think, feel, and act.

What challenges will this new era bring us? What will be the impact of wearable technologies on our current accepted information security principles? Will we need to revamp them? Will we be forced to add new principles? Or will we even have to abandon principles once taken as a mainstay?

Wearcams connected to the Internet and sharing images in real time pose new challenges to confidentiality. Wearable GPS (Global Positioning System) devices (as simple as most common cell phones) shrink the frontiers of personal privacy. Losing our smartphone puts us out of sync with the world and makes us unavailable to others. These all exemplify issues that wearable technologies may raise to information security principles. But among the principles, we are particularly interested in the impacts of wearable technologies on authenticity

Background

To better understand the authenticity challenges posed by wearable technology, this section defines and discusses the key concepts involved, namely Authenticity and Wearable Technology.

Authenticity

Explicitly suggested by Parker [1998] as an information security principle, in this chapter the word authenticity

Just as a modern server uses its digital certificate to prove its authenticity, employing it to authenticate its messages, in the Middle Ages kings had personal seals, which were used to seal the important communications of their kingdoms. Seals prevented the message from being read by others without the knowledge of the intended receiver, thus ensuring the message’s confidentiality. The recipient could also verify the message’s integrity and authenticity. If the seal remained intact, the message received would be the one the sender wrote, i.e., it will not have been subjected to any modification, and so maintained its integrity. In this case, the proof of a message’s authenticity rested on the fact that the seal was unique and not transferable.

Even though the concepts of integrity and authenticity have resemblance, they should not be confused, as explained by Parker [1998]: we may assure that a certain message is faithful, but it may not be authentic, e.g., due to misappropriation of its author’s identity, or if a user enters false information into a computer system it may have violated authenticity, but as long as the information remains unaltered, it has integrity. Thus, it is crucial to rigorously define each security principle, in order to clarify and contrast meanings and to effectively plan their compliance.

Decomposing the adopted definition of authenticity, we can immediately separate this principle in its main components, namely by dividing the definition into three key parts, two of which refer to information and the third to individuals, entities and processes. Hence,

Information Has to Be in Accordance with a Particular Reality: Reality is understood as the context in which the information is produced. For information to be authentic it must be conform to its reality. Moreover, the verification of information’s genuineness and validity depends on that context: the same information in different contexts may be evaluated differently in terms of authenticity, and,

The Genuineness and Validity of Information Are Verifiable: The genuineness of information alludes to its original state, as opposed to the possibility of being a fabrication or imitation. The use of the word validity refers to situations of information being worthy of acceptance as legitimate to meet a certain goal and of being free of misrepresentation. These proprieties or states of information need to be verified, i.e., to be able of being tested (confirmed or falsified) by such means as experiment or observation, in order to conclude about its authenticity; or

An Individual, Entity, or Process Is Who It Claims to Be

: This third component presents a major challenge. Firstly, we need to identify and define the subject in question, i.e., to what, or to whom, we want to prove its authenticity. After this identification, it is required to prove if the subject is authentic, i.e., that the subject actually corresponds to whom it claims to be. The word “

prove the authorship nor the sequence of a set of performed actions if the information or the subjects involved are not authentic.

A concept that is often confused with authenticity is authentication, being in some cases considered or at least assumed as synonyms or indistinguishable (cf. [Ben Aissa et al. 2009] and [Liu et al. 2012]). However, we cannot regard them as synonymous, since they belong to entirely different classes in the domain of information security: while authenticity should be regarded as a principle of security, authentication is a security control intended to assure that a claimed feature of an entity is correct [ISO/IEC 2014]. In the realm of this discussion, authentication is a security process that conducts the test of authenticity of a subject. Another security process related to the proof of authenticity of an entity is identification. While in identification a security control plays an active role aiming to identify an entity, for example, via biometric devices, in authentication a security control plays a more passive role–the entity firstly claims to have a certain identity and afterwards the security control aims to confirm the identity of the entity, for example, through a login procedure (username/password). It is common to characterize authentication as a 1:1 process (check if an entity is who it claims to be—a one to one match) and identification as an n:1 process (among a set of n possible entities, find the one whose identity is being claimed).

Importance of Authenticity

We live in a society dominated by the continuous exchange of information, a 24/7 news cycle, posts on the wall of our social network, and many other forms and media. However, given the ease of today’s communication, we must take into account the quality of information that reaches us, especially if it is authentic. Certainly, not all information that reaches us is reliable–it might have been handled or the source might not be credible. Therefore, we must seek to ensure that information is in accordance with our reality and that it is genuine, so as not to allow that a fictional or even a false reality is being projected upon us. Hence, it becomes increasingly important to be equipped with mechanisms that allow us to make this validation and selection. Since cybercrime is a growing phenomenon [Zingerle and Kronman 2013], computer forensics assumes greater prominence. In the realm of these investigations, authenticity plays a crucial role, in that in any dispute, legal or judicial, it is important to confirm that the information stored in our devices, purportedly resulting from our actions, is authentic [Zhao et al. 2012]. In forensic investigations, that information may be used as a basis for profiling [Marrington et al. 2007], allowing the tracking of our actions and places visited. In case the authenticity of the information source is compromised, we may face problems ordering the events, resulting in severe inconsistencies in the timeline of facts. This issue can be a major problem during the evidence validation process [Marrington et al. 2011].

Indeed, the information collected can only be used as evidence if its authenticity is guaranteed, as well as the authenticity of its source and the processes involved in its production or transmission; otherwise, one cannot ensure the non-repudiation of certain actions. If on the one hand, without this guarantee, someone or some entity or process can impersonate another and thereby incriminate it—in this case the accused would be punished unfairly, on the other hand, a criminal aware of this lack of guarantee can propose the elimination of proof—in this case the accused escapes unpunished for a crime that was eventually perpetrated.

In health systems, intelligent transport systems, government applications, and other critical areas where the exchange of information is crucial, ensuring authenticity of information as well as of its origin is essential. When remotely monitoring a patient’s physical activity, ensuring correctness and authenticity of the received data is imperative. This applies not only to the fidelity of the monitoring process, but also to prevention mechanisms for fraud in case treatments are, for instance, financed by health insurance contracts [Alshurafa et al. 2014]. For intelligent transportation systems, the authenticity of information and of its source is very important, since invalid information may result in serious traffic accidents and human losses [Zhao et al. 2012]. On the electronic government front, as an illustration, South Korea adopted SecureGov, a framework of multiple security mechanisms to prevent illegal use and leakage of information, to prevent illegal modification of information, and to ensure the authenticity of the user and delivered information [Choi et al. 2014].

Threats to Authenticity

Following the adopted definition for authenticity, the threats to authenticity can be grouped into two main groups: those that endanger the authenticity of information and those that endanger the authenticity of subjects. Although one may find various examples of threats against authenticity, some paradigmatic cases will suffice to illustrate attacks on authenticity.

Despite the constant efforts to ensure the authenticity of information, through such controls such as the use of encryption, digital signatures, checksums, and transactions confirmation, these mechanisms are also the target of counterfeiting attempts, some of them successful. The success of these attacks can be explained, at least in part, by the encryption flaws made public and by the growing of private computing power. Indeed, given the evolution of technology and its increased dissemination and ease of access, it is becoming less complicated to bring together technological means with considerable capacity at reasonable cost to exploit those flaws [Pearce et al. 2013].

A similar situation may happen in computer systems. For example, in terminals that access different platforms and services via a Single Sign-On (SSO) authentication policy, the threat of user impersonation is also present. Indeed, Mayer et al. [2014] documented five systems that have been the target of successful SSO attacks. In these cases, the authentication process was considered successful, i.e., the subjects were allowed access by the system, however, they were not authentic—although authenticated they were not really who they claimed to be. Moreover, the subject authenticated by the system may be authentic, but at a later time the subject using the system (already authenticated) may not remain the same, it may change to a different subject, who may not have authorization to use the system. This requires the system to periodically verify the current user’s authenticity, for instance, by checking if the user is who it claimed to be by analyzing its key stroke dynamics [Monrose amd Rubin 2000].

Wearable Technology

Since the beginning of human civilization, the desire to create utensils and tools has been present in our mind. Humanity aims to increase its (particularly sensory) capacity by developing tools as items of clothing or as accessories. These artefacts, such as watches, glasses or others embedded in clothes, that expand human capabilities, were named by Rodrigo [1988] as external cognitive prostheses.

Wearable technology and devices have emerged with the intrinsic human wish for possession and use of such devices and with the evolution of technology, in particular ubiquitous computing, i.e., computer systems that cooperate with each other transparently to the user [Cirilo 2008]. These devices, some very sophisticated in terms of technology, features and computing power, have different functions employed in different areas such as health, entertainment, fitness, production, among many others, and are becoming increasingly common in our daily routines.

Thus, we define wearable device as an artifact—i.e. something made or given shape by man, such as a tool [Collins 2015]—that can be used as an external prosthesis in order to extend the cognitive and sensory ability of the person who uses it.

Evolution of Wearable Devices

Haunted with the so-called millennium bug, the year 2000 arrived and with it the era of mobility. Devices that hitherto had no network connection began to come equipped with wireless networking systems via Bluetooth, WAP, GPRS, or Wi-Fi. All the devices were now (able to be) networked.

In 2010, Nike launched the Nike+Sportsbands, a bracelet that by using motion sensors gives important information about training. Since then, there have been many other fitness gadgets featuring GPS functionalities and data synchronization with other devices such as mobile phones. It has become common to share in social networks our travelled paths, whether it is running or riding a bicycle.

Today, in the era of IoT, we have actual computers that fit in the palm of our hand, and whose complexity makes us think about the future. We can easily imagine a smart hand or foot or a Bluetooth shoelace that tightens itself. From the simple analogue watch and glasses, going through Casio CMD-30B, perhaps the most famous of all, to smartwatches, the evolution of such devices has been extraordinary, as well as the technology that supports them, such as nanotechnology, wireless communication systems, new textiles fibers, among many others.

There are many practical applications of today’s wearable technology, in numerous areas, and in many cases using devices and earlier technology. For example, RFID tags have seen their applicability increase with the advent of these new devices. Another example is FedEx that has equipped many of its delivery vehicles with hands-free ignition and the vehicle security control system that is activated by an RFID bracelet that the driver has on his arm [Schell n.d.]. Many sensors are now used in clothing that enable us to remotely monitor the vital signs of outpatients [Hurford 2009].

Wearable devices are also widely used in medicine and in different scenarios. In cases of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a childhood severe encephalopathy, the Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) is a less invasive treatment to control epileptic seizures [Jobst 2010]. Wearable devices, such as bracelets, watches or glasses, can also contribute to a better social interaction for those who have limitations in communicating or socializing, as in the case of autistic individuals [Kirkham amd Greenhalgh 2015].

Given the usefulness and potential of wearable devices, in particular smartwatches, NASA challenged developers to design an app for astronauts to use when they are in space [Geier 2005]. We will not know what the future holds, but certainly this stimulating and exciting evolution will continue.

Icons

There are different types of wearable devices that by their functionality and usage stand out from the rest. Below are presented some of those devices, considered here as icons.2

Google Glass (Google)

: Despite the project’s “ Narrative Clip (Narrative): Designed to be attached to clothing, this camera can be used as a decorative accessory and shoots two photos per minute automatically, thus helping to create a kind of logging of the places one has been to. It comes with internal storage capacity, GPS and it can synchronize photos with applications by Wi-Fi and Bluetooth LE. Photographs are captured with the local reference and date of origin, in order to enable research and may also be shared in social networks.

Motorola Moto 360 (Motorola): This is a smartwatch equipped with Google Android operating system, thereby enabling the development, installation and use of applications similarly to what happens with a smartphone. This watch comes equipped with GPS, Wi-Fi, motion sensor, camera and integrated sound system. It even allows viewing and making videos.

Mi Band (Xiaomi): Equipped with motion sensors, this bracelet indicates to the user the number of steps traveled over a day/night. After synchronization provided by a smartphone application, the user may have an estimate of the calories consumed during a certain period of time.

Chameleon 4V+ (Weldline/Air Liquide): This is a protection mask for welders. Like a helmet, it is placed on the head and, thanks to its display controlled by sensors sensitive to light and to stronger radiation that can cause injury to the human eye, darkens at the time of welding and lightens right away. Its functioning is similar to sunglasses, but the color of the lens varies according to the light and radiation to which it is subjected to.

Genesis-Artificial Pancreas (Pancreum): This device intends to function as an artificial pancreas, by reading the glucose level in blood. It allows the monitoring of the readings through an application available for smartphone. It can automatically inject insulin if necessary.

The brief review of these icons suggestively illustrates the range of areas where such devices can operate and the versatility of their applications.

Types and Categories of Wearable Devices

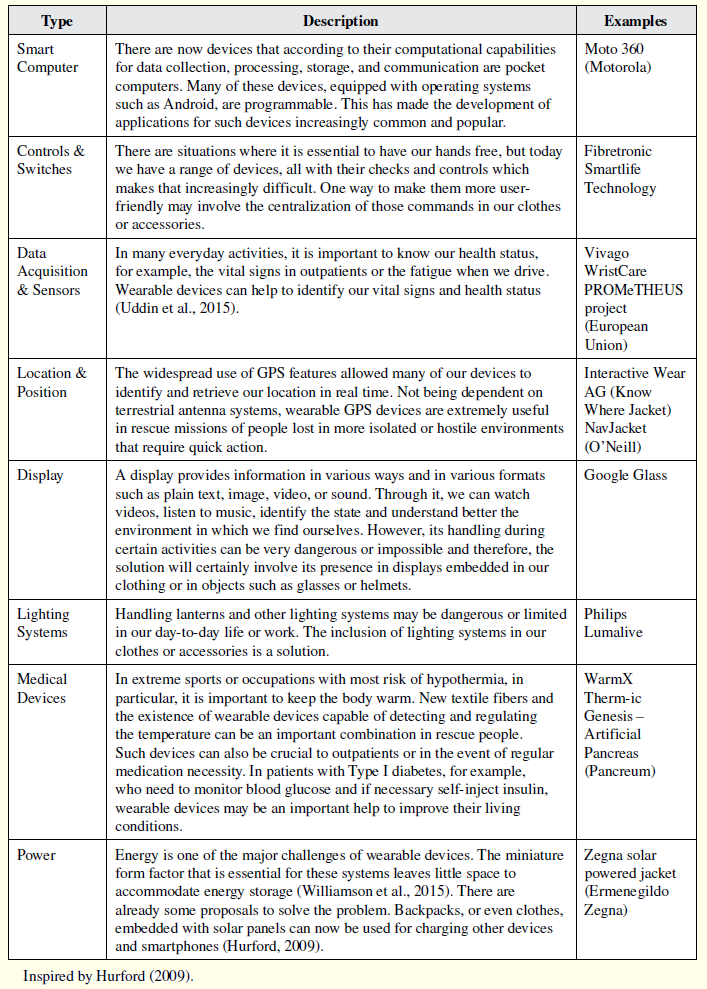

There are several types of wearable devices. Depending on its working method and technology employed they can be grouped by types. Table 1 shows major types of wearable devices following the work by Hurford [2009].

Table 1: Wearable Devices Types

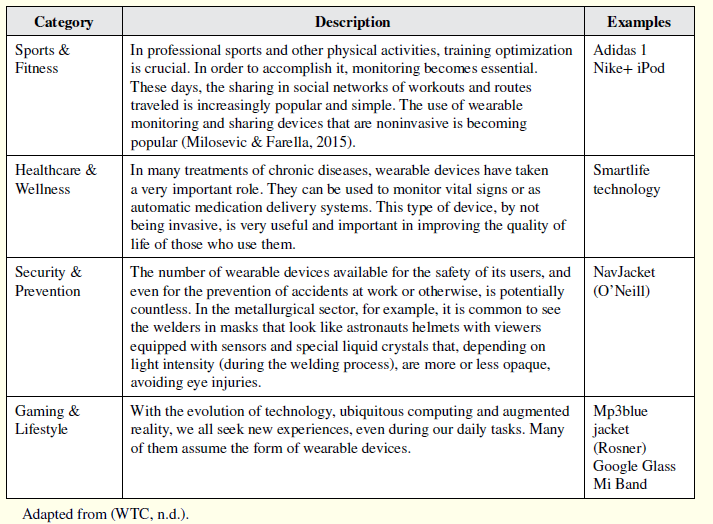

Based on the Innovation World Cup categories organized by Wearable Technologies Conference [WTC n.d.], these devices can also be grouped into categories according to their core market sector, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Wearable Devices Categories

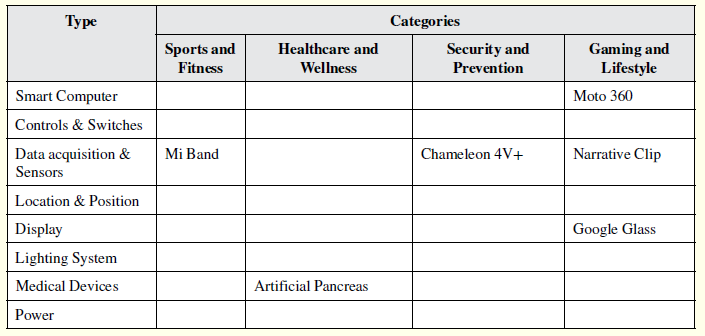

Taking into consideration the types and categories of wearable devices shown in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively, the wearable devices previously considered icons may be ranked as displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Icon Wearable Devices Classified by Category and Type

Authentivity Analysis Framework for Wearable Devices

In order to classify wearable devices in terms of authenticity, it is useful to first define and understand their environment, herein termed as the Wearable Ecosystem.

The Wearable Ecosystem

Communication is certainly a vital function for all living beings, humankind being no exception. Over the years a lot has changed, moving from simple communication between people—Human-to-Human (H2H)—to other forms of communication, especially at a distance, such as mail, telephone or Internet.

There are numerous forms and architectures for human communication systems, from mail to email. With the increasing use of mobile phones, the Short Message Service (SMS) and the Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) have become increasingly important data transmission mechanisms.

With the evolution of technology as well as the wearable computing capabilities and networks, including Wi-Fi, it is possible to have these devices networked, acting as networked nodes, and performing functions of clients or servers (peer-to-peer).

Given the nature of wearable technology, these isolated or connected devices, in an M2M (Machine-to-Machine) scheme, can be considered, in terms of communication, as external frontiers of the person who uses them with its environment, thereby defining an interface between the holder and the outside.

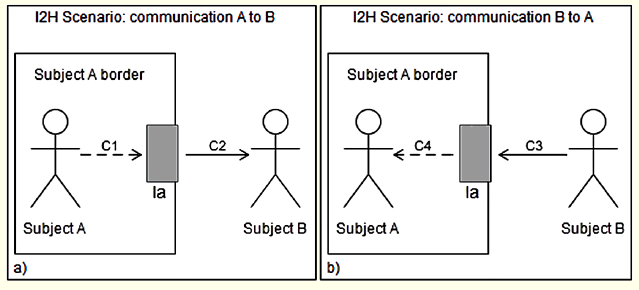

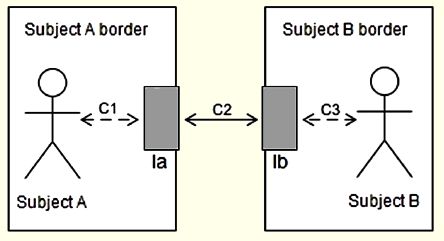

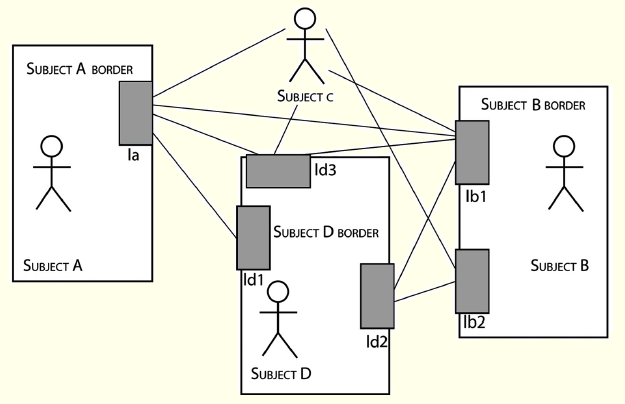

As its user interface, these devices can define two types of communication. In an interaction between two persons, subject A equipped with device Ia (interface a) and subject B equipped with device Ib (interface b) can establish the following kinds of communications, in a notation à la Unified Modeling Language (UML) and with Cn indicating the time sequence of communication:

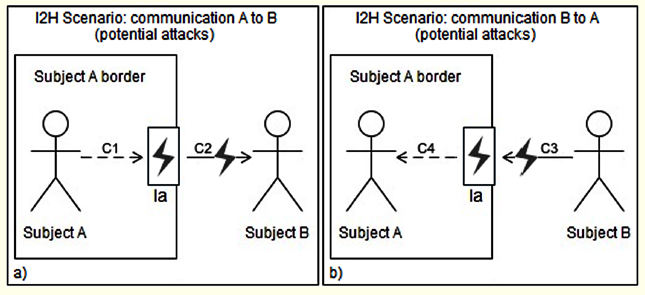

Interface-to-Human (I2H): The communication begins in A but the message is issued by A’s interface (Ia) directly to subject B (Figure 1a). When B responds to A (Figure 1b) the response will be received and delivered by A’s interface. Subject A will receive B’s message directly from A’s interface, and not from B.

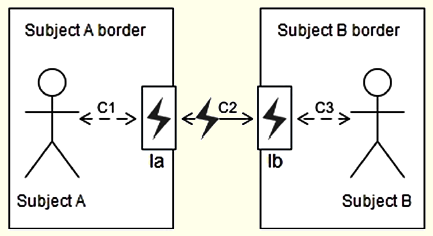

Interface-to-Interface (I2I): A message from A is sent via A’s interface (Ia) that communicates with subject B via its interface (Ib), and vice versa (Figure 2). The communication can occur in both directions, but each subject only communicates directly with his own interface.

Figure 1: Interface-to-Human Communication Scenarios

Figure 2: Interface-to-Interface Communication Scenario

In both scenarios, I2H and I2I, there is no direct contact between subjects: all communications are mediated. Whereas in I2H scenario this mediation is partial, since subject B is not using his interface, and communicates directly with A’s interface (connection represented by C3 in Figure 1b), for B there is no border notion. In I2I scenario, the communications of A to B and of B to A are completely mediated, i.e., no subject sends a message to outside his border, directly. Each one communicates to the outside using its interfaces.

Figure 3: Internet of People

Based on natural ecosystem definition—a system formed by the interaction of a community of organisms with its environment [Ecosystem n.d.], a Wearable Ecosystem could be defined as a system formed by organisms: the humans—as users—and their wearable devices—as artefacts. In this ecosystem all interactions are mediated by artefacts.

This new ecosystem presents new challenges to civilization as a whole. Taking into account the development of machine automation over the last three centuries, Davenport and Kirby [2015] organized that evolution into three eras:

Era One (19th Century): Machines take away the dirty and dangerous—industrial equipment, from looms to the cotton gin, relieves humans of onerous manual labor;

Era Two (20th Century): Machines take away the dull—automated interfaces, from airline kiosks to call centers, relieve humans of routine service transactions and clerical chores;

Era Three (21st Century): Machines take away decisions—intelligent systems, from airfare pricing to IBM’s Watson, make better choices than humans, reliably and fast.

In Era Three of machine automation evolution, wearable devices are in a privileged position compared to any other machine, given their proximity to their users. These devices can collect users’ behaviors, reactions and routines more accurately than any other machine, because they do it in a transparent and non-invasive way, that is, without the user being conditioned [Xu et al. 2008]. This proximity, combined with their ability to collect and process data, makes these devices able to feed and teach their smart systems, including decision-making systems.

Should the Turing test be changed? So far this test uses two types of players: the man and the machine. In terms of test, we have the duel between human mind and machine. With the presence of wearable intelligent interfaces, we now have three types of possible players:

A human (as a being, standalone);

The machine (standalone);

A hybrid human-machine (a human equipped with its artefacts).

In the hybrid human-machine scenario, where machine represents the set of wearable interfaces holding the capability of communication controlled by AI algorithms, it may not be possible to distinguish what belongs to the human and to his or her devices. Will intelligent wearable interfaces be able to pass the Turing test and so impersonate a human? If so, we may consider a new kind of impersonation, thus putting at risk the guarantee of its authenticity: it is not an individual who is impersonating another, but it is one of their features that is impersonating him or her.

The privileged position of wearable devices in relation to their users makes it easy for them to intrude in the communications they mediate, pursuing attacks such as MITM, particularly in communications identified with C2 and C3 in Figures 4 and 5. This privileged position, and the access to their users’ personal information—allowing them to set a profile of their users and thus behave similarly—can also allow them to go through one, or more, real actors in communication (i.e., via impersonation). In this scenario, it might make sense to also consider a new type of attack, namely interface-as-a-person.

Figure 4: Potential Attacks (identified by bolt signal) under I2H Communications

Figure 5: Potential Attacks (identified by bolt signal) under I2I Communications

The Framework for Analysis

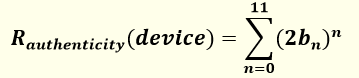

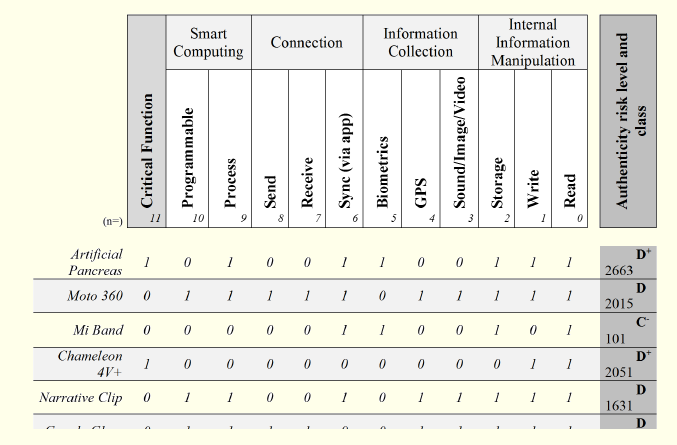

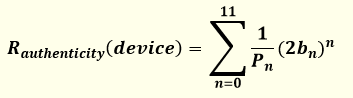

In order to be able to determine the authenticity risk of a wearable device, taking into consideration its capabilities and features, the authors propose a classification framework based on a scale of 1 (20) to 4095 (212-1) points, in which the value 1 is the lowest authenticity risk level of a device and 4095 the highest possible value for that risk.

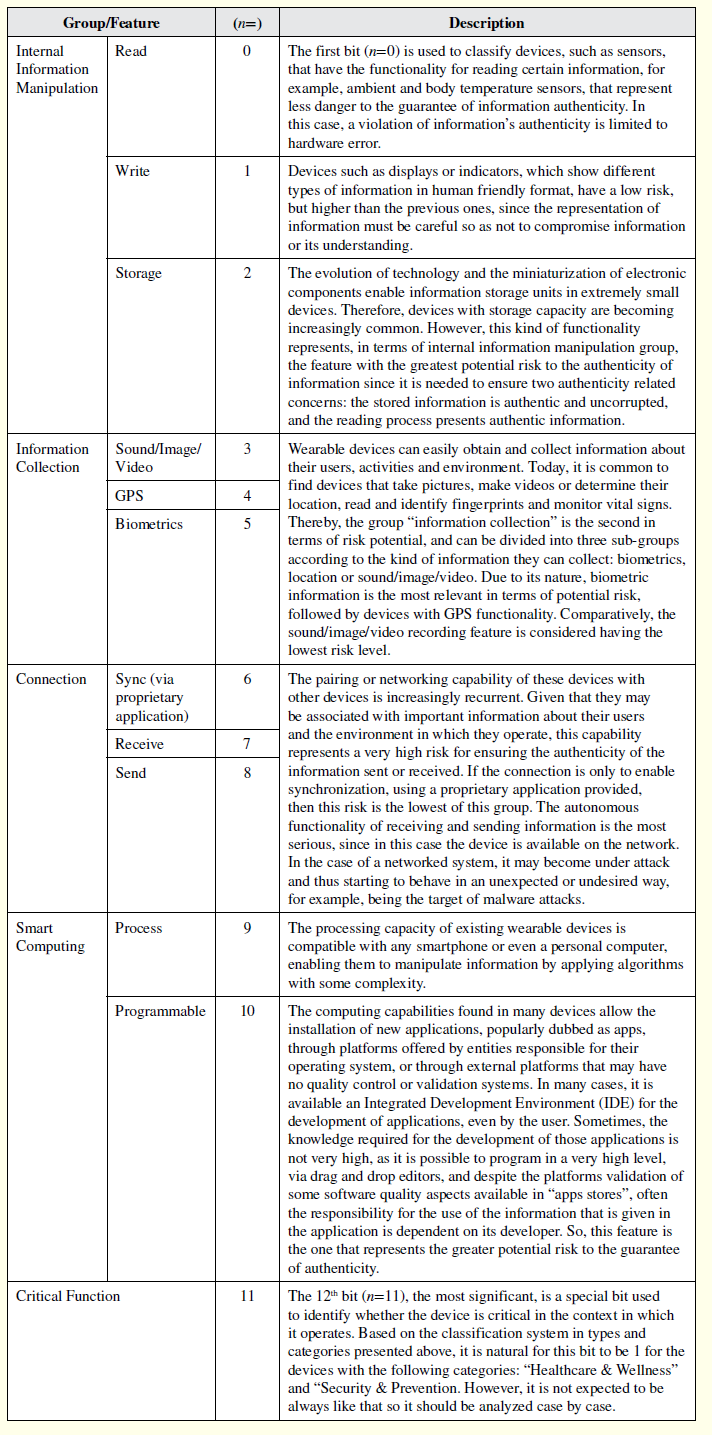

The rating system (cf. Table 4) is a system based in binary 12 bits (1 + 11 bits), in which each bit indicates whether a feature is present or not in the device under study. This classification system is based in a table with the most important features of devices sorted by their degrees of risk of not ensuring the authenticity principle in descending order, from left to right (11 bits). Hence, the most problematic features to authenticity, for example, the computational capabilities, occupy the most significant bits (to the left). The functionalities conveying less risk, such as simply reading data, are located in the lower bits (to the right). The 12th bit (n = 11), the most significant, is a special bit and it intends to identify whether the device is critical in the context in which it operates.

Table 4: Rating System Used in the Framework

The authenticity risk level—Rauthenticity—for a specific wearable device can be determined by computing Equation 1:

where bn represents the value (zero or one) of the bit at position n (0-11).

The use of binary representation and the above formula allows two devices to have the same classification, if and only if, they have the same functions, so the comparison between devices is linear.

As an example, Figure 6 shows the classification for two non-critical devices (b11 = 0), using the suggested rating system. The first is a temperature sensor and the second is a smartwatch.

Figure 6: Non-critical Wearable Device Classification Examples

Of the two non-critical devices used for illustration, the one with a lower risk level is the sensor because information that can be collected is just the temperature and it has no critical role. The smartwatch, in spite of not playing a critical role, has a higher risk level because it has access to a large set of its user’s information that can manipulate and disseminate without intervention or even the knowledge of its

user.

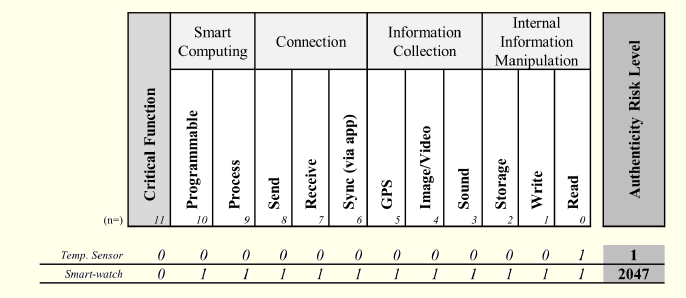

Simplifying the classification system and its scale, the risk can be translated into the 12 classes, in human friendly format, depicted in Figure 7. To promote the intuitive understanding about the classes range, code levels, from D+ to A-, are employed (colors can also be used to flag classes—red for the higher levels of risk and green for lower levels, with orange and yellow being used in the intermediate classes). The most significant non-zero bit of the rating of a device defines the device’s risk class.

Figure 7: Authenticity Risk Classification Levels

The classification level main classes (A to D) have the following heuristic meanings:

A=Attention;

B=Be careful;

C=Caution;

D=Danger (or even Death).

Icon Devices Analyses

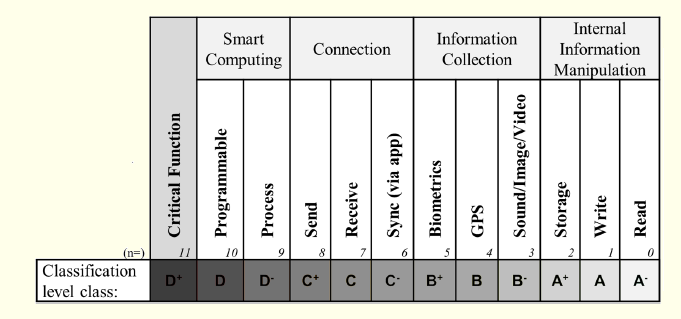

Figure 8: Icons Classification

Of the icon wearable devices presented, the simplest is the welding mask (Chameleon 4V+), given that in terms of technology only has light sensors and a display that controls the brightness that comes to the user. However, it plays a critical role given the protection it provides to its users, therefore, assuring that the components of this device (hardware) are authentic is very important, otherwise it may compromise its operation, which means, as a result, that its class is D+. Also rated as D+, even though it has a risk value higher than the first, is the artificial pancreas, given its vital role as well as the technology it employs. In this case, the risk is not only related to its hardware but also to its firmware and software.

The smartwatch (Moto 360), the smart glasses (Google Glass) and the camera (Narrative Clip) are the most popular of the list, and possibly the most used due to their features and similar manner of use. They have an operating system and enable their programming though the installation of applications. In this classification system they have class D. In spite of not playing a critical role, they have access to a large set of their users’ information that they can manipulate and disseminate without intervention or even knowledge of their users.

The device with the lowest risk level is the fitness bracelet (Mi Band) because, despite being close to its user 24 hours per day, the information that can be collected is very limited (e.g., it is confined to the movements and the cardiac activity of the wearer). Information diffusion is also limited, since the device only communicates with other devices (not wearable) through a provided application. In this case, the risk can be considerable if the application that allows synchronization and information collection does not comply with an appropriate level of security.

Preventive Factor

Based on the ratings of the devices analyzed, we observe that, regardless of the context (critical or not) in which they operate, most wearable devices are in class D, i.e., the highest level of risk for authenticity. If we associate to this high potential risk their privileged position in relation to their users, the information they have access to and their computational and communication capabilities, we conclude these types of devices may pose a real threat to authenticity. Therefore, preventive measures should be defined in order to mitigate their potential risk.

Considering that the application of preventive measures targets a particular feature of the device (corresponding to the index n), which allows the reduction of the potential risk of the device, and that may be defined by the Pn coefficient, its impact can then be included in authenticity risk calculation formula shown previously in Equation 1, as given by Equation 2:

where bn represents the bit value (zero or one) in the position n (0-11) and Pn the value of the preventive coefficient correspondent to n. The preventive coefficient is a heuristic value and can take values from N , i.e., all natural numbers (1,2,3, ...). The value 1 for Pn coefficient means that no preventive action was applied.

As an example, considering a critical sensor, if we use two sensors in parallel (using the mean value as final value) the estimate preventive coefficient could be 2 for the correspondent index (n=11). For the read feature (n=0) if we use sensors with different serial numbers the probability of failure of both sensors may be reduced, in this case the estimated preventive coefficient could be 2.

Certainly, it may not be feasible to remove features from these kind of devices or to completely eliminate the risk for authenticity. However, it may be possible to mitigate this risk. The preventive factor arises in this framework as a mechanism to represent the risk reduction for authenticity associated with each feature of the device (based on its respective preventive coefficient) and, concomitantly, to reflect this risk mitigation in the device’s authenticity risk value. This way, if a wearable device was designed and developed to promote authenticity, the rating system of the proposed framework will take it into account, distinguishing the risk level of the device from other devices with similar features but lack of preventive mechanisms.

Solutions and Recommendations

Based on the result of the classification system and its application, one recommendation and a possible solution are proposed to mitigate the risk for authenticity on wearable devices.

The classification system may be used as a mechanism to inform end users about the risks that are present when using a specific device. By including the respective class in the device’s package, this information can be used as an element of choice between devices.

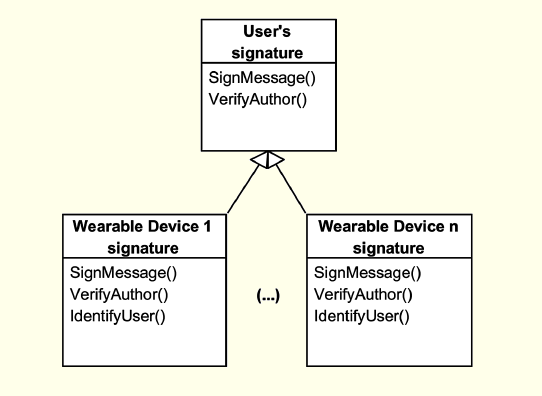

A possible control to mitigate the risk for authenticity on these devices is Hierarchical Digital Signatures.

Digital signatures can provide the assurance and evidence of the identity and provenance of the author, i.e., the signatory [Saxena and Chaudhari 2012]. However, given the possible types of communication that may occur in the presence of increasingly sophisticated wearable devices, as previously discussed and outlined in Figures 4 and 5, the inclusion of the traditional digital signature, as we know it, may not be sufficient.

These devices can impersonate their users by sending messages to themselves or by manipulating users’ messages. It is argued that to ensure authenticity of the authorship of each of the exchanged messages, they must be digitally signed with the signature of the authentic author. A message sent by a device (even on the advice of its user) must be signed with its signature, and never with the user’s signature.

Incidentally, a device should not sign by its user (or owner) in order to prevent impersonation attacks. Signing a device must guarantee the identification of his authorship and of its user. In this respect what is proposed is a new hierarchical scheme for digital signatures. The hierarchy of digital signatures may be represented in a diagram of signatures and their extensions (cf. Figure 9) in a similar manner as a class diagram, from object oriented programming paradigms.

Figure 9: Proposed Signatures Hierarchy

This new scheme allows the receiver of a message to identify the author through its signature and if it was intermediated by any interface, identifying which interface was used and who owns it. The human author cannot repudiate the authorship of a particular message, if it was initially signed with its signature.

In order to illustrate how this mechanism works, it is necessary to recall the communication scenario of Figure 4. In the scenario presented in Figure 4a, subject A starts a communication to subject B; this communication will be mediated by Ia. The message is then signed by subject A and transmitted to A’s interface. This interface will sign the message with its digital signature (this signature is actually an extension to the signature of its user). Subject B receives the message and can verify the authorship of the source (in this case Ia) as well as that it is an intermediated communication by an interface, since there is information about a user (subject A). These two levels of message signature prevent impersonation, i.e., the IaaP attack, and ensure the authorship of the original author (subject A), and the interfaces that mediate the communication (Ia). In the scenario illustrated in Figure 4b, subject B in response to subject A (communication C3) uses its own signature to sign the message and to send it to subject A, however, this communication will be mediated by A’s interface (Ia). Interface Ia receives and displays a message to the subject who is using it. This subject A can then validate the authorship of the message and verify there are no intermediaries (subject B has no interface), ensuring this way the authenticity of the message and its authorship.

This new mechanism will bring new challenges to manufacturers of this type of device, as it will be necessary to develop a security kernel responsible for this new feature.

One possible solution would be to implement a Reference Monitor (cf. [Rushby 1981]). A reference monitor will be the most critical part of this new security kernel, controlling access to objects and acting as a mediator of transactions with the system. This component must be:

Tamper-proof (it cannot be modified nor avoided),

Always invoked (single point through which all requests for access must go) and

Small enough to be subject to analysis and testing, making it possible to ensure its completeness.

In this case, the reference monitor can be conceived as a digital signatures manager, storing the digital signatures of device and owner, and ensuring their authenticity in terms of source and use.

Future Research Directions

The focus of this work is on the challenges of wearable technologies from the point of view of authenticity as a security principle. The proposed classification system is applicable for classifying the risk for authenticity of information and subjects. Subsequent research work could extend the analysis to other security principles, for instance integrity or availability of information. The hierarchical architecture for digital signatures could also be evaluated from the point of view of other security principles.

It will also be interesting to involve and consult people, as users of these technologies. A survey could help to understand their level of knowledge on this topic, and to identify their awareness about the risks underlying these technologies. Based on their opinions as users or future users of these technologies, it would be important to validate the utility of the classification system proposed in this chapter, in order to identify possible requirements, changes or new directions to follow, so that it may be an aid in creating a culture of security. Finally, it would be interesting to try to conduct work aimed to normalize the scale for rating the preventive factor, so that its current heuristic nature could be replaced by a systematic quality.

Conclusion

From the evolution of wearable devices, not only have new devices resulted with many new features that may be important aids in our activities, but also a number of new challenges to the information security field, such as the ones concerning the assurance of authenticity.

Given the capabilities integrated in wearable devices, and their wide range of applications, it becomes necessary to take some precautions in their use. The framework presented in this chapter intends to alert and sensitize users of this technology to the potential risks and dangers to which they may be subjected, providing them with a classification tool for evaluating and comparing this type of devices. It is not intended to call into question the usefulness of this technology, but to make their potential users aware of the associated authenticity risks and of the effectiveness of preventive measures that may mitigate the corresponding dangers.

Based on usage scenarios of wearable devices, potential attacks that can be carried out, putting into question the authenticity of the information involved or the authenticity of the sender of the message have been discussed. In order to promote the authenticity, both of information and subjects involved in the interactions, a mechanism of hierarchical digital signatures was suggested.

Certainly, the evolution of these devices will not stop here and new challenges will emerge, an expected situation that requires, from now on, the management of wearable technologies security issues.

Discussion Points

Considering the definition of authenticity adopted in this chapter, authentic information does not cease being authentic just because the person who transmitted it is not authentic. In legal disputes, should information from these sources be accepted as evidence?

Would it be possible and useful to employ a graphic class classification system for the risks to information authenticity in user manuals of wearable devices, in order to educate some less careful users of the risks to which they are exposed in terms of information authenticity?

If the evolution of wearable interfaces, namely in increased computational capability and artificial intelligence capacity, enables them to imitate their user, representing that user as its interface with another subject or interface, should the Turing Test be extended?

Will wearable devices ever be capable of simulating their users (human)?

Which are the rules for, and roles of, users of these kinds of devices?

Will wearable devices be capable of imitating another human being, inducing their users to believe in a fabricated reality?

Regarding the “ Will we exchange wearable technologies or will one’s wearable technologies be so personal that without them one would feel as if naked?

Questions

Given the expected development of wearable technology, wearable devices may undertake a more active role in their relationship with the user, as suggested with the ecosystem presented in this chapter. What kind of security controls may be developed and used to mitigate the risk for information authenticity?

How can we verify the genuineness and validity of that information?

What can be understood by a “ What are the key components of a “ Which kind of mediated communications can be found in a “ On the Wearable Ecosystem like the one presented by the authors in Interfaceto- Human (I2H) or Interface-to-Interface (I2I) communications, will attacks such as man-in-the-middle and interface-as-a-person be the only kind to occur?

Might a user of a wearable device be obliged to reject the authorship of a certain communication or its content, attributing it or the manipulation of its content to a wearable device?

Is the hierarchical system of digital signatures enough to mitigate the risks of information authenticity per se?

Can the classification system for authenticity risk presented in this chapter help raise the awareness of users of wearable devices on the risks of authenticity, as a tool for user education?

References

Alshurafa, N., J. A. Eastwood, M. Pourhomayoun, S. Nyamathi, L. Bao, B. Mortazavi and M. Sarrafzadeh (2014). Anti-cheating: Detecting self-inflicted and impersonator cheaters for remote health monitoring systems with wearable sensors. 11th International Conference on Wearable and Implantable Body Sensor Networks (BSN), Zurich (Switzerland). DOI: 10.1109/BSN.2014.38

Ben Aissa, A., R. K. Abercrombie, F. T. Sheldon and . A. Mili (2009). Quantifying security threats and their impact. Proceedings of the 5th Annual Workshop on Cyber Security and Information Intelligence Research: Cyber Security and Information Intelligence Challenges and Strategies, 26.

Casio (n.d.). Operation Guide 1138 1173 Casio. Retrieved from Casio Support Online Web site: http://support.casio.com/storage/en/manual/pdf/EN/009/qw1173.pdf

Chinaculture.org (2010). The Story of the Chinese Abacus: The Abacus with Chinkang Beads. Retrieved from http://www.chinaculture.org/classics/2010-04/20/content_383263_4.htm

Choi, J. J. U., S. Ae Chun and J. W. Cho (2014). Smart SecureGov: mobile government security framework. Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, 91–99.

Cirilo, C. (2008). Computação Ubíqua: definição, princípios e tecnologias. Retrieved from: http://www.academia.edu/1733697/Computacao_Ubiqua_definicao_principios_e_tecnologias

Collins (2015). Collins English Dictionary—Complete and Unabridged. Retrieved October 8 2015 from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/artifact

Davenport, T. H. and J. Kirby (2015). Beyond Automation—Strategies for remaining gainfully employed in as era of very smart machines. Harvard Business Review 93(6), 59–65.

Dhillon, G. amd J. Backhouse (2000). Technical opinion: Information system security management in the new millennium. Communications of the ACM 43(7), 125–128. DOI: 10.1145/341852.341877

Dohrn-van Rossum, G. (1996). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Ecosystem (n.d.). American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, fifth edition. Retrieved October 11 2015 from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/ecosystem

El País (2011). Horror en la isla de Utoya: El País, July 23. Retrieved from http://internacional.elpais.com“ Fanthorpe, L. and P. Fanthorpe (2007). Mysteries and Secrets of Time (Volume 11). Dundurn Press Toronto.

Geier, B. (2005). NASA wants you to make a smartwatch app for astronauts. Fortune. Retrieved from http://fortune.com

Glasseshistory (n.d.). History of Eyeglasses and Sunglasses. Retrieved from http://www.glasseshistory.com/

Hager, E. B. (2011). Explosions in Norway. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

Hurford, R. D. (2009). Types of smart clothes and wearable technology. In J. McCann, J. and D. Bryson (Eds.), Smart clothes and wearable technology, 25–44. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing. DOI: 10.1533/9781845695668.1.25

ISO/IEC (2014). ISO/IEC 27000—Information technology—Security techniques—Information security management systems—Overview and vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

Jobst, B. C. (2010). Electrical stimulation in epilepsy: Vagus nerve and brain stimulation. Current Treatment Options in Neurology 12(5), 443–453. DOI: 10.1007/s11940-010-0087-4

Karlsson, S. and A. Lugn (n.d.). The history of Bluetooth. Retrieved from: http://www.ericssonhistory.com/changing-the-world/Anecdotes/The-history-of-Bluetooth-/

Kirkham, R. and C. Greenhalgh (2015). Social Access vs. Privacy in Wearable Computing: A Case Study of Autism. Pervasive Computing 14(1), 26–33. DOI: 10.1109/MPRV.2015.14

Liu, H., S. Saroiu, A. Wolman and H. Raj (2012). Software abstractions for trusted sensors. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, 365–378. Ambleside (UK).

Lymberis, A. (2004). Wearable eHealth Systems for Personalised Health Management: State of the Art and Future Challenges. IOS press.

Marrington, A. D., G. M. Mohay, A. J. Clark and H. L. Morarji (2007). Event-based computer profiling for the forensic reconstruction of computer activity. AusCERT Asia Pacific Information Technology Security Conference (AusCERT2007): Refereed R&D Stream.

Marrington, A., I. Baggili, G. Mohay and A. Clark (2011). CAT Detect (Computer Activity Timeline Detection): A tool for detecting inconsistency in computer activity timelines. Digital Investigation 8, S52–S61. DOI: 10.1016/j.diin.2011.05.007

Mayer, A., M. Niemietz, V. Mladenov and J. Schwenk (2014). Guardians of the Clouds: When Identity Providers Fail. Proceedings of the 6th edition of the ACM Workshop on Cloud Computing Security, 105–116. Scottsdale, AZ: ACM.

Milosevic, B. and E. Farella (2015). Wearable Inertial Sensor for Jump Performance Analysis. Proceedings of the 2015 workshop on Wearable Systems and Applications, 15–20. ACM. DOI: 10.1145/2753509.2753512

Monrose, F. and A. D. Rubin (2000). Keystroke dynamics as a biometric for authentication. Future Generation Computer Systems 16(4) 351–359. DOI: 10.1016/S0167-739X(99)00059-X

Parker, D. B. (1998). Fighting Computer Crime: A New Framework for Protecting Information. John Wiley & Sons.

Pearce, M., S. Zeadally and R. Hunt (2013). Virtualization: Issues, security threats, and solutions. ACM Computing Surveys 45(2), 17. DOI: 10.1145/2431211.2431216

Rhodes, B. (n.d.). A brief history of wearable computing. Retrieved from http://www.media.mit.edu/wearables/lizzy/timeline.html

Rodrigo, M. A. (1988). Ser Y Conocer: Peculiaridades Informáticas de la Especie Humana. Cuadernos Salamantinos de Filosofia 15, 5–20.

Rushby, J. (1981). The Design and Verification of Secure Systems. ACM Operating Systems Review 15(5), 12–21. DOI: 10.1145/1067627.806586

Saxena, N. and N. S. Chaudhari (2012). Secure encryption with digital signature approach for Short Message Service. 2012 World Congress on Information and Communication Technologies (WICT). 803–806. DOI: 10.1109/WICT.2012.6409184

Schell, D. (n.d.). RFID Keyless Entry And Ignition System Speeds FedEx Couriers. Retrieved from http://www.bsminfo.com/doc/rfid-keyless-entry-and-ignitionsystem-speeds-0001

Stinson, B. (2015). Nokia’s 3310: the greatest phone of all time. Techradar. Retrieved from http://www.techradar.com

Teixeira, A. and F. de Sá-Soares (2013). A Revised Framework of Information Security Principles. In Furnell, S. M., N. L. Clarke and & V. Katos (Eds.), Proceedings of the European Information Security Multi-Conference EISMC 2013, IFIP Information Security Management Workshop.

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind 59(236), 433–460. DOI: 10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

Uddin, M., A. Salem, I. Nam and T. Nadeem (2015). Wearable Sensing Framework for Human Activity Monitoring. Proceedings of the 2015 workshop on Wearable Systems and Applications, 21–26. DOI: 10.1145/2753509.2753513

WTC (n.d.). Innovation Worldcup Categories. Retrieved from: http://www.wearabletechnologies.com/innovation-worldcup/categories/

Williamson, J., Q. Liu, F. Lu, W. Mohrman, K. Li, R. Dick and L. Shang (2015). Data sensing and analysis: Challenges for wearables. Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC), 2015 20th Asia and South Pacific, 136–141. DOI: 10.1109/ASPDAC.2015.7058994

Xu, Y., W. J. Li and K. K. Lee (2008). Intelligent Wearable Interfaces. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. DOI: 10.1002/9780470222867

Zhao, M., J. Walker and C. C. Wang (2012). Security challenges for the intelligent transportation system. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Security of Internet of Things, 107–115. DOI: 10.1145/2490428.2490444

Zingerle, A. and L. Kronman (2013). Humiliating Entertainment or Social Activism? Analyzing Scambaiting Strategies Against Online Advance Fee Fraud. 2013 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW), 352–355. Yokohama.

Zolfagharifard, E. (2014). Is this the first wearable computer? 300-yearold Chinese abacus ring was used during the Qing Dynasty to help traders. Daily Mail. Retrieved from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk

Key Terms and Definitions

Artifact: Something made or given shape by man, such as a tool that can be used as external prosthesis in order to extend the cognitive and sensory ability of the person who uses it.

Impersonate: Ability of a person, process or thing to assume a character or appearance of another one, normally for fraudulent proposes.

Interface: A wearable device that assumes, in a communication scenario, the bridge between a person (that is using this device) and the external entities.

Interface-as-a-Person (IaaP): The privileged position of the wearable devices in relation to their users, makes it easy for them to intrude in the communications they mediate, and combined with the access to their users’ personal information—allowing them to set a profile of them and thus behave similarly—can also allow them to go through one, or more, real actors in communication.

Interface-to-Human (I2H): In a communication between subjects A and B, the communication begins in subject A but the message is issued by his/her interface directly to subject B. When B responds to A, the response will be delivered and received by A’s interface. Subject A will receive B’s message directly from A’s interface, and not from B.

Interface-to-Interface (I2I): In a communication between subjects A and B, a message from A is sent via A’s interface that communicates with subject B via its interface, and vice versa. The communication can occur in both directions, but each subject only communicates directly with his own interface.

Internet of People (IoP)

Wearable Ecosystem: A system formed by organisms—the humans, as owners—and their wearable devices, as artefacts. In this ecosystem all communications are mediated by artefacts—as interfaces, assuming two schemas: I2H and I2I.

Endnotes

1 In this work we chose the word principle over alternatives, such as property or requirement, to refer to the concepts of confidentiality, integrity, availability, etc., in order to convey the sense of guiding foundation for the efforts to protect information and information–related assets.

2 The information about these devices was retrieved from respective project/manufacturer official websites.