Original source publication: Teixeira, A. and F. de Sá-Soares (2013). A Revised Framework of Information Security Principles. In Furnell, S. M., N. L. Clarke and V. Katos (Eds.), Proceedings of the European Information Security Multi-Conference EISMC 2013—IFIP Information Security Management Workshop. Lisbon (Portugal).

A Revised Framework of Information Security Principles

Centro ALGORITMI, Departamento de Sistemas de Informação, Universidade do Minho, Guimarães (Portugal)

Abstract

Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability are referred to as the basic principles of Information Security. These principles have remained virtually unchanged over time, but several authors argue they are clearly insufficient to protect information. Others go a step further and propose new security principles, to update and complement the traditional ones. Prompt by this context, the aim of this work is to revise the framework of Information Security principles, making it more current, complete, and comprehensive. Based on a systematic literature review, a set of Information Security principles is identified, defined and characterized, which, subsequently, leads to a proposal of a Revised Framework of Information Security Principles. This framework was evaluated in terms of completeness and wholeness by intersecting it with a catalog of threats, which resulted from the merger of four existing catalogs. An initial set of security metrics, applied directly to the principles that constitute the framework, is also suggested, allowing, in case of adverse events, to assess the extent to which each principle was compromised and to evaluate the global effectiveness of the information protection efforts.

1. Introduction

The generalization of Information Systems (IS) to all areas of society, coupled with the constant evolution of Information Technology (IT), configures an ecosystem where it is relatively cheap and easy to store, process, and share information. This ecosystem presents several opportunities for organizations and individuals, profoundly changing the way they communicate, organize, and interact. The same ecosystem, however, raises a host of risks to the information manipulation activities, justifying concerns and investments in the protection of information and related resources.

Traditionally, information and IS protection has been guided by three basic principles: Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability, often referred to as the CIA model, with the acronym capturing the first letter of each of the three principles. However, some authors argue that these principles, although basilar and important, may not be sufficient since they do not address all Information Security (InfoSec) threats and have not evolved at the same pace of the threats. As Parker [1998, p. 211] noted fifteen years ago, We need a new model to replace the current inarticulate, incomplete, and incorrect descriptions of information security. The current models limit the scope of information security mostly to computer technology and ignore the sources of the problems that information security addresses. They also employ incorrect meanings for the words they use and do not include some of the important types of loss such as stealing copies of information and representing information.

Over the years, the dissatisfaction with the CIA model led several authors to redefine existing principles or to propose new principles that complement and update the traditional ones. Among those authors are Parker [1998], Dhillon and Backhouse [2000], Stamp [2006], and Whitman and Mattord [2011].

We use the expression information security principles to mean those attributes of information and other IS resources that may work as guidelines, goals, or focal points for the information protection efforts. The importance of the principles is that by identifying them we are actually defining information security, deducing from them InfoSec objectives, concerns, and scope. The acceptance of the foundational or ontological role of the principles for the activity of information security management predicates that it is important to base the implementation of InfoSec controls on a firm, complete and updated set of InfoSec principles.

In this work we propose a revised framework of information security principles. Prior to the proposal, we undertake a review of the literature on information security principles, followed by an exercise where we relate InfoSec threats to the principles. The revised framework is composed of a set of definitions and a schematic structure for the organization of the principles. In the end, we suggest an initial set of metrics to evaluate the extent of InfoSec principles compromise.

2. Analysis of Literature on Information Security Principles

The first step we took towards the revised framework of InfoSec principles was the identification and characterization of the attributes literature indicates explicitly or implicitly as information security principles.

The nodal point for this review was the set of definitions found in the literature for those attributes. From an operational point of view, we used three main sources of definitions. The first source was dictionaries where we sought the definition for the pivotal word of each concept reviewed (two dictionaries were consulted: a dictionary of the Portuguese language and a dictionary of the English language, namely the dictionary of the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon and the Merriam-Webster dictionary). The second source of definitions were publications by international organizations in the field of InfoSec, such as standards published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), as well as historically relevant references, e.g. Information Technology Security Evaluation Criteria (ITSEC), Generally Accepted Information Security Principles (GAISP) and Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT). The third source of definitions were documents were individual authors delineated their understanding of InfoSec principles. From these sources, a total of seventeen security attributes were identified.

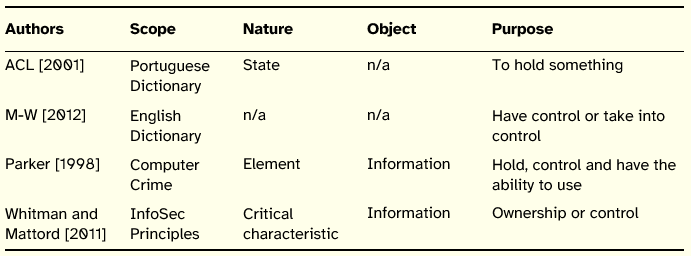

In order to compare the definitions we established a schema composed of four parameters: scope where the definition was presented, i.e., the domain or theme of the work reviewed; nature assigned to the principle defined; object focused in the definition; and the purpose assigned to the principle.

To avoid a tedious recitation of definitions, we chose to present the reviewed definitions in tabular form. For each of the concepts discussed we condensed the definitions in a table that identifies the proponents of the definition and its scope, nature, object, and purpose. For those cases where it was not possible to fill all the fields, we marked the missing values as n/a (not available).

These tables provide a general and immediate overview of the terms and expressions used, facilitating the identification of common and divergent points between the authors, as well as to verify if there is a common sense among the definitions advanced for the same concept.

2.1 The Triad

The first group of concepts reviewed composes the traditional triad of InfoSec CIA (Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability). For a long time these three principles formed the fundamental model on which InfoSec rested.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is one of three basic and traditional InfoSec principles and, probably, the one that is most easily and frequently associated with security. Historically, it has military roots and it was the first principle formalized in a seminal InfoSec document the TCSEC (Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria), based on the Bell-LaPadula lattice model.

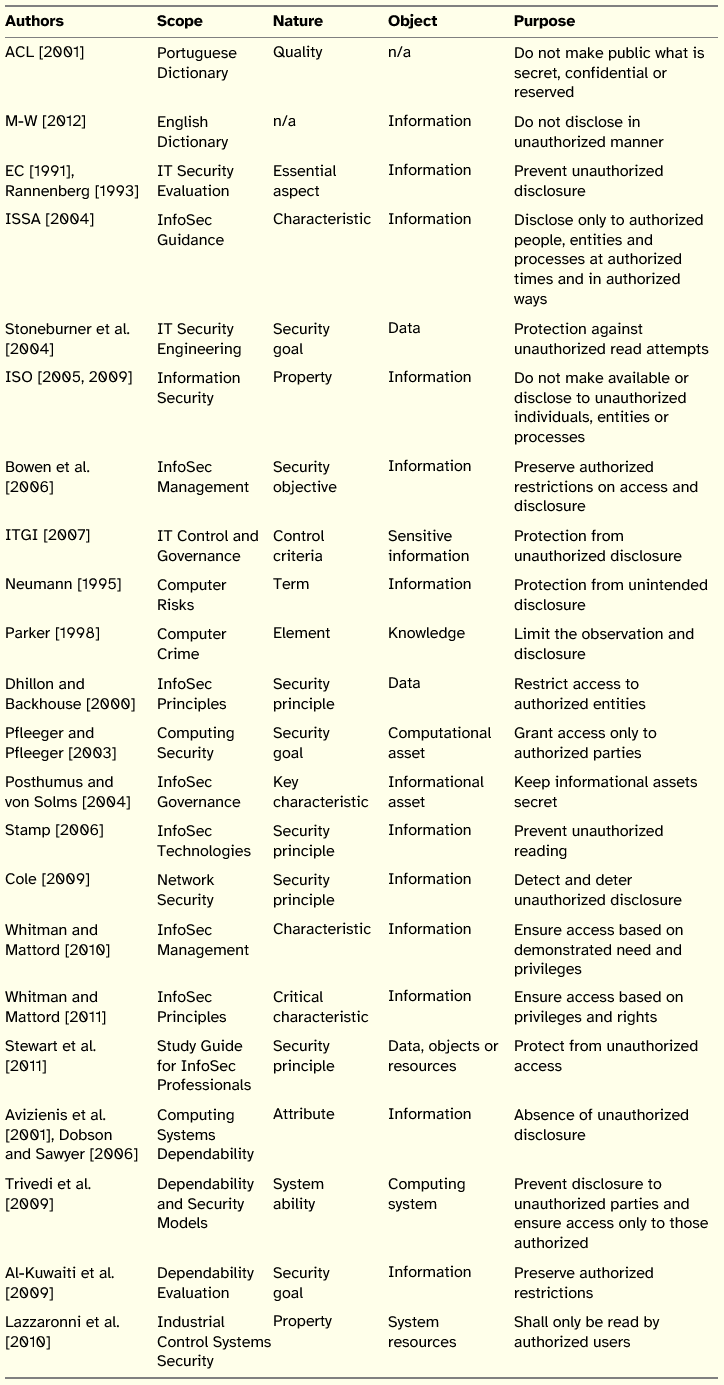

Table 1 summarizes the review made on the concept of confidentiality.

Table 1: Summary of Confidentiality Definitions

This is the principle that deals with secrecy, covering information in storage, during processing, and while in transit.

In terms of scope, more than half of the definitions for confidentiality are presented in the context of InfoSec, with an emphasis on the management and governance of InfoSec and on the principles and guidelines of InfoSec.

Regarding the nature of the concept, there is no clear trend, although goal, characteristic, and principle stand out.

In what concerns the objects targeted by the definitions there is, unsurprisingly, the predominance of information, followed by data and systems.

The purpose of confidentiality is, according to most authors, to not disclose, to not make available and to not allow access to information by unauthorized entities or people or in unauthorized ways. Authors like Parker [1998] and Pfleeger and Pfleeger [2003] have called attention for the fact that confidentiality should not have as sole concern the disclosure of (secret) information, but also voluntary or involuntary observation, printing or simply knowing that a particular information asset exists. Underlying these concerns is the theme of access to information and its control, which is strongly related to the authorization process. An additional observation is that confidentiality may be temporary [ISSA 2004], meaning that information may be classified as confidential for a specific period of time.

In general it can be concluded that, based on the reviewed definitions, there is consensus among the authors, but without any conception standing out and whose definition is adopted generally.

Integrity

The principle of integrity is also part of the traditional model of InfoSec. For the general public, however, it is probably less noticeable than confidentiality. It followed confidentiality in terms of formalization, conveyed in the Biba model.

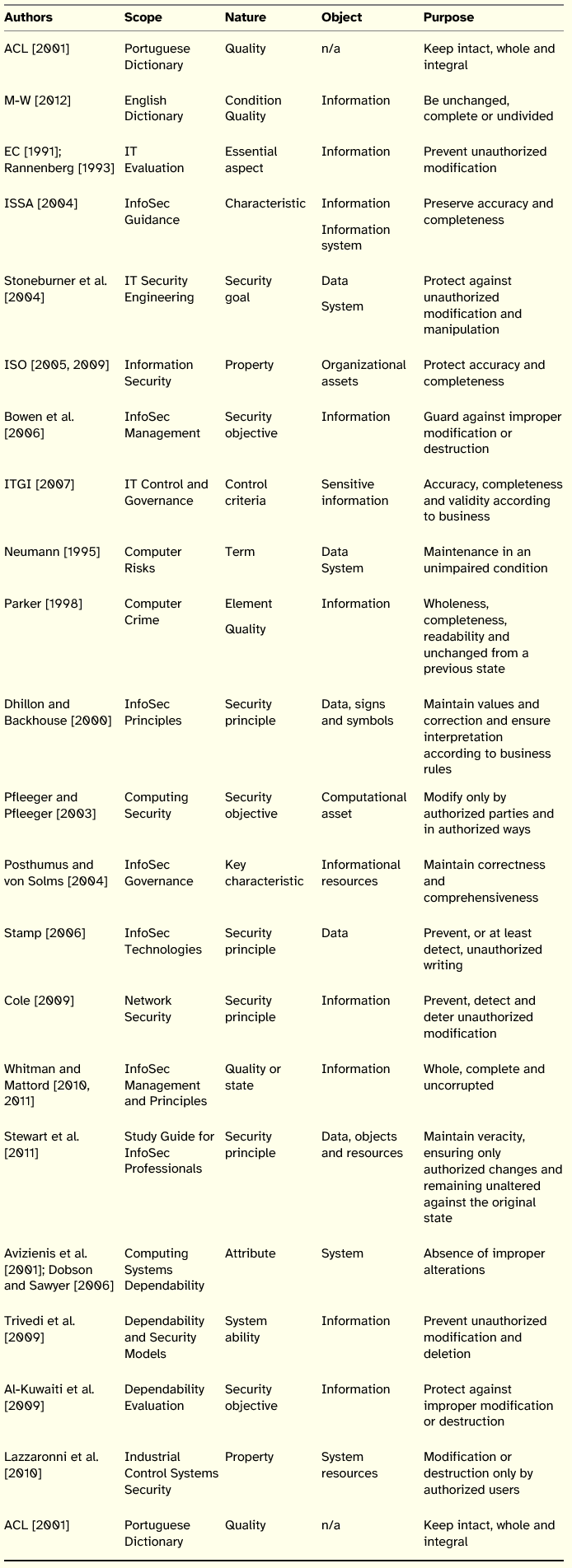

Table 2 summarizes the review made on the concept of integrity.

Table 2: Summary of Integrity Definitions

Underlying the concept of integrity is the notion of change, with the majority of definitions addressing the access to information resources and the associated authorization process.

In terms of scope, the analysis is similar to the principle of confidentiality, since most definitions are proposed in the domain of InfoSec.

Regarding the nature of the concept, there is also a similarity to the principle of confidentiality, to the extent that there is no predominant term, standing out principle, objective, and characteristic.

In what concerns the objects targeted by the definitions, there is a focus on information, data and systems. It is also important to note that ISO standards are focused on organizations assets, i.e., anything that has value for the organization, be it tangible or intangible. In contrast to confidentiality, there are authors who put under the umbrella of integrity both information and systems. The inclusion of systems is justified by the fact that unauthorized modifications or faults may also target systems, which may provoke unauthorized modifications in information, e.g. the case of processed data produced by an ill-conceived computer program.

Considering the purpose of integrity, there are two major distinct streams. On the one hand, the principle of integrity ensures that information is complete, accurate, and correct. On the other hand, integrity refers to the prevention of unauthorized manipulation, modification, and destruction. In this sense we cannot say there is consensus among the definitions, although it is understood that the two streams are complementary.

Evidence of alteration of information raises some challenges, since it may not be possible to compare the current state of information with its original state. Parker [1998] argues that instead of considering the original state, we should take into account the previous state of information, although this may prove difficult for computed data or for information without source documents.

A relevant issue associated with integrity is its contextual and behavioral dimension. The definition provided by ITGI [2007] stresses that the accuracy, completeness and validity of information should be judged according to the business values and expectations. The impact of the interpretation of information by people on integrity had already been underlined by Dhillon and Backhouse [2000], who argued for the need of users to have the capability to interpret information according to the business rules of the organization they pertain to. If there is a deficit of this capability, even if the values of data, signs and symbols are maintained, the integrity of information will be compromised.

Availability

Availability is the third component of the traditional model for InfoSec. Probably, it is the principle whose compromise is most immediately evident for users.

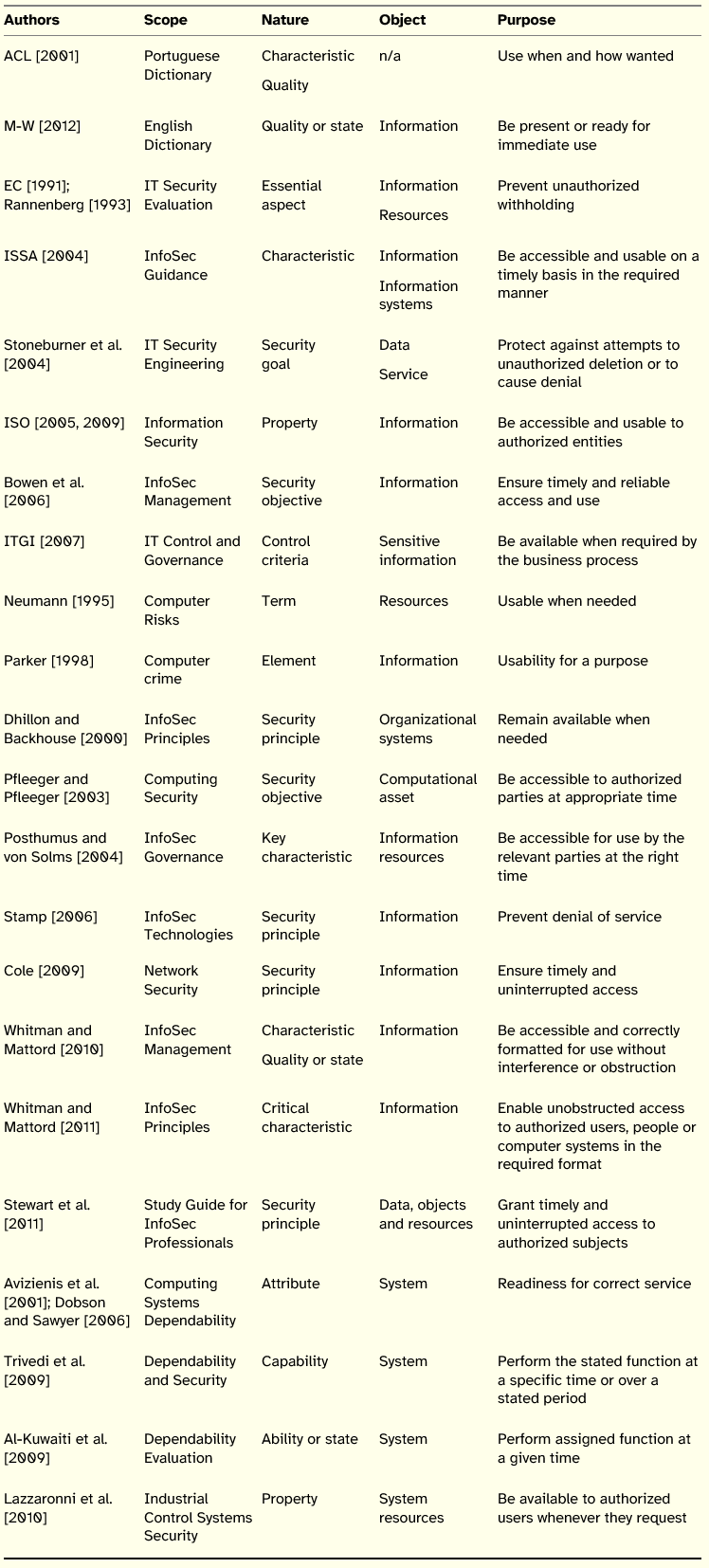

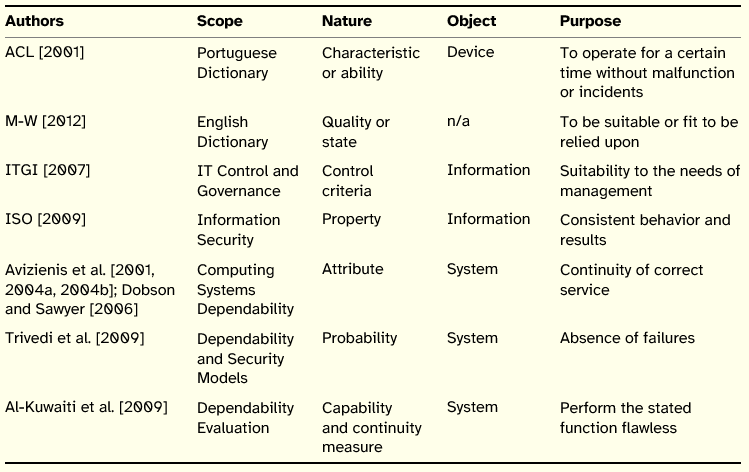

Table 3 summarizes the review made on the concept of integrity.

Table 3: Summary of Availability Definitions

Regarding the scope and nature of availability, the conclusion to be drawn is similar to the one made for the principles of confidentiality and integrity, i.e., availability is proposed mainly on studies related to InfoSec, being named as a principle, characteristic and objective, or ability when definitions focus on systems. From the point of view of the object it stands out information and systems.

In what concerns the purpose, it is relevant to distinguish between definitions with the focus on information and on systems, although their meaning is very close. An important issue relates to the access and possibility of using information and systems in a timely manner and, for systems, performing their function in a given time. However, and in contrast to the previous two principles, the concern with access is not uniquely placed on its restriction (as before, only authorized agents should be grant access to the information), but the main concern is to being able to grant access to those entitled to it. Although access to information is important, the definition advanced by the ISO standards suggests that being able to access information does not imply that the information is usable. The usability of information had already been remarked by Parker [1998] and elaborated by Whitman and Mattord, who qualify access in terms of authorization, format, and obstruction.

A final note regards the timing issue pointed by Posthumus and von Solms [2004]. Not only there may be a right moment for making information available, but also availability is always tested at a specific moment of time.

2.2 Extensions of the Triad

After reviewing the CIA model, we now present definitions for a set of ten attributes that do not make part of the InfoSec traditional framework, but may function as extensions of the CIA triad.

The identification of these attributes resulted from the initial search that led to the finding of works that, besides the CIA model, refer to other attributes that can also be considered as InfoSec principles, taking into account their definitions and characteristics. The same systematic review process was applied to this set of attributes. The analysis of the corresponding definitions followed the same procedure previously employed with the difference that, in most cases, the number of definitions is much more reduced.

The ten attributes that will be discussed next are privacy, reliability, authenticity, non-repudiation, accountability, safety, survivability, utility, accuracy, and possession.

Privacy

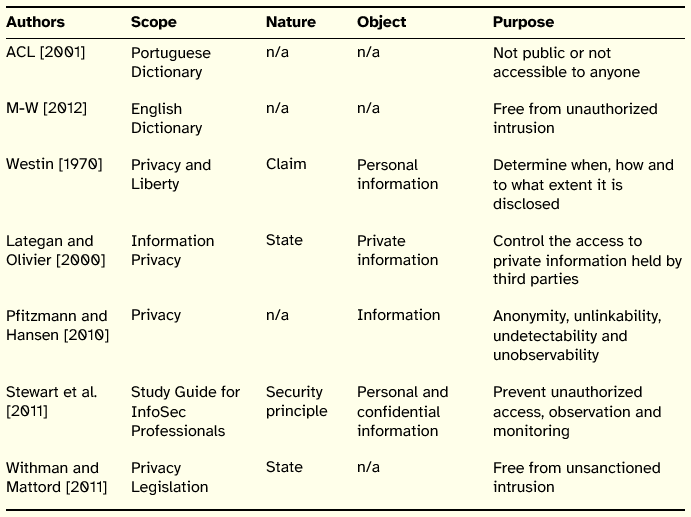

Privacy is one of the most discussed topics in the field of InfoSec [Whitman and Mattord 2011] and probably one of the most easily understood by society in general. This is a concept closely related to the concept of confidentiality. Table 4 summarizes the review made on the concept of privacy.

Table 4: Summary of Privacy Definitions

The scope of the definitions, with the exclusion of those found in the dictionaries, is always presented in the context of privacy itself.

Concerning the definitions nature, privacy is referred to as a state, principle and even as a claim.

The object of the reviewed definitions is information, although this results directly from the focus of the literature search. However, the ACL [2001] definition suggests that the meaning of the word is related to people and not to information. A similar view had already been advanced by Parker [1998, p. 227], who argued that privacy refers to a human and constitutional right or freedom, preferring to reason in terms of confidentiality of information in order to protect the privacy of people. Indeed, Prosser [1960] defined the privacy rights of an individual as opposition to several actions, including the public disclosure of embarrassing private facts about an individual. Over time, the use of the word privacy has expanded to encompass other objects, as can be noticed in the conceptualization of Clarke [2006] who identifies the privacy of the person, the privacy of personal behavior, the privacy of personal communications, and the privacy of personal data.

Regarding the purpose, there are two distinct senses. One has to do with control of personal information held by third parties, including control over the disclosure of that information, and the other concerns non-intrusion, anonymity, unlinkability, undetectability, and unobservability. Pfitzmann and Hansen [2010] have proposed and characterized these last terms for a better understanding of the privacy concept, helping to clarify the privacy construct and to distinguish it from confidentiality. The clarifications advanced by those authors for the supporting concepts of privacy are the following: anonymity a subject is not identifiable within a set of subjects; unlinkability it is not possible to sufficiently distinguish if an item of interest (subject, message, or action) is linked to another item(s) of interest; undetectability it is not possible to sufficiently distinguish if an item of interest exists or not; and unobservability it refers to the anonymity of an item of interest or to the undetectability of a subject.

In the case of privacy, the owner of the information is generally the individual to whom the information relates (the person in personal information). There may be other entities that hold the information, however, they usually act as custodians of that information.

Reliability

The concept of reliability is used in several contexts with a special emphasis on the domain of systems dependability. Table 5 summarizes the review made on the concept of reliability.

Table 5: Summary of Reliability Definitions

The principle of reliability, unlikely the previous reviewed principles, is mainly proposed in the realm of systems instead of information. Both ITGI and ISO documents do not associate reliability directly to information security.

Regarding the nature of the concept, in the perspective of systems it is presented as an attribute or ability. In the perspective of information it is presented as a property.

The object that is mainly targeted by the definitions is the system, with the purpose of the principle being the continuity of service delivery or the flawless function of a system. Actually, Trivedi et al. [2009] suggest that reliability may be conceived as a measure of the continuity of service.

Authenticity

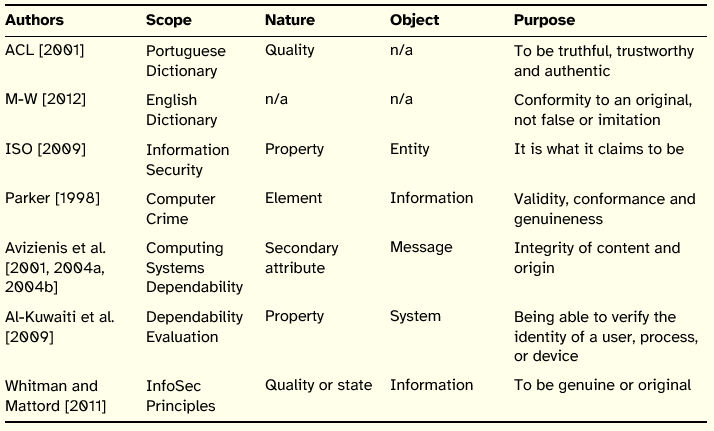

In contrast to reliability, the principle of authenticity is applicable to information itself. It is also often applied to processes and people as it can be observed in Table 6.

Table 6: Summary of Authenticity Definitions

This principle is proposed in the realms of InfoSec and dependability. As regards the nature, the definitions reviewed do not convey a clear tendency. In what concerns purpose, it is relevant to distinguish between the authenticity of users, i.e., the confirmation of their identity, and the authenticity of information in the sense of being genuine.

At a first glance, there is a certain degree of overlap between authenticity and integrity. Probably, one of the main supporters of the distinction between the two principles is Parker [1998]. This author proposed a pair of principles formed by integrity and authenticity, in which the first relates to completeness, and the second to validity. According to his view, an entity is authentic if it represents the desired facts and reality. To illustrate the differences between the two principles, Parker exemplifies with a scenario in which a software distributor obtained a computer game program from an obscure publisher. The distributor modified the name of the publisher on the media and title screens to that of a well-known publisher and then made copies of the media. Without informing either publisher, the distributor disseminated copies of the program in a foreign country. Parker observes that the program had integrity because it identified a publisher and was complete and sound. However, it was not an authentic game from the well-known publisher, i.e., it did not conform to reality since it misrepresented the publisher of the game.

Non-Repudiation

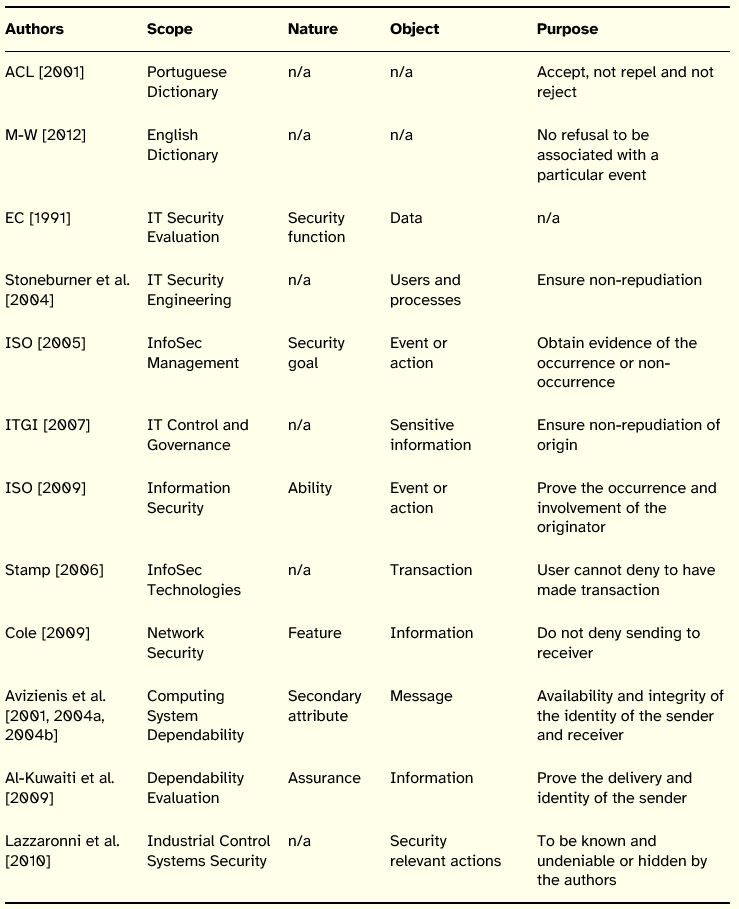

The principle of non-repudiation shares some of the features of authenticity. Giving the apparent overlap between the concepts, Parker [1998] argues that non-repudiation is contained and covered by authenticity, since it is a form of misrepresentation by rejecting information that is actual valid, not including this principle in his InfoSec framework. A different view was conveyed by the USA Department of Defense, who added non-repudiation to the traditional InfoSec model [DoD 2002]. Therefore, it is important to analyze definitions for non-repudiation proposed in other contexts. Table 7 summarizes the review made on the concept of non-repudiation.

Table 7: Summary of Non-Repudiation Definitions

Non-repudiation is proposed mainly in InfoSec, although it was not possible to isolate a consensual nature for this principle. This principle plays a central role in communications security, where it is important to prove that a message originated from a specific sender (non-repudiation of origin) and that a message was accepted by a specific receiver (non-repudiation of reception).

The object focused by definitions varies, with information and actions or events receiving a special accentuation.

Concerning the purpose, there is an emphasis on the identification of a particular entity and the unequivocal association of that entity with an event or action. The essential point of this concept rests on the capability to ensure that a certain event did occur or did not occur and, in the first case, to be able to identify the entities involved. In other words, all actions relevant to InfoSec made in a system are known and cannot be denied or hidden by their authors [Lazzaroni et al. 2010].

A final observation regards the importance of the inverse of repudiation. Besides having the ability to demonstrate that a certain agent has actually made certain transactions even when the agent denies it, it is also important to be able to demonstrate that a certain agent has not performed certain actions even if the agent claims to have made such transactions.

Accountability

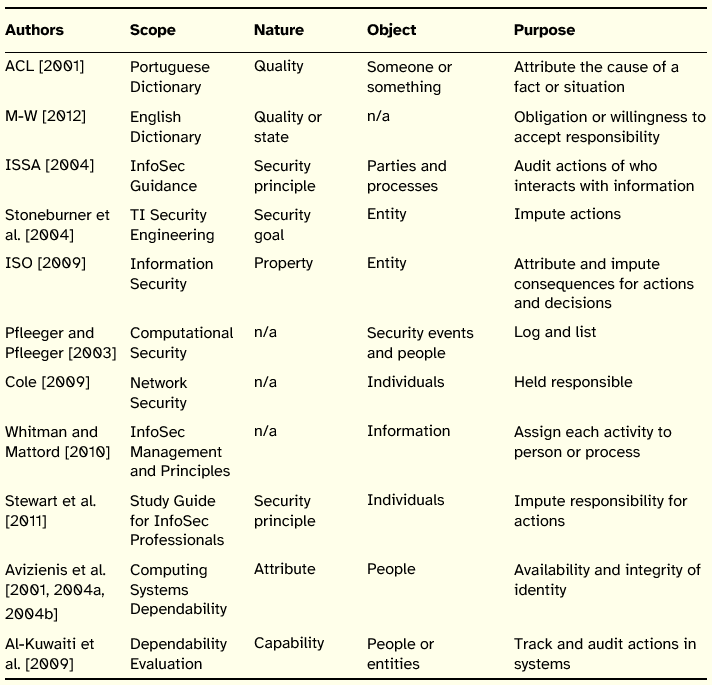

Accountability is presented by several authors as an InfoSec principle, despite not applying directly to information itself, but to the people that manipulate information. In the definitions analyzed it is immediately recognizable some parallels between the definitions of non-repudiation and accountability, especially in aspects related to the identity or identification of people. Table 8 summarizes the review made on the concept of accountability.

Table 8: Summary of Accountability Definitions

This principle is mainly versed in studies related to InfoSec and the users are its main object. The purpose of accountability shares similarities with the purpose of non-repudiation, in that both seek to attribute responsibility for events or actions to a given entity. From the definitions reviewed, it was also possible to verify the connection between accountability and the activities of control and auditing, leading Whitman and Mattord [2011] to observe that accountability is also known as auditability. Still, in the realm of dependability, non-repudiation is usually applied to the transmission of messages, while accountability is applied to peoples identity. The main concern, though, is to be able to assign and impute to a specific entity the consequences of a certain action or decision that was detrimental to the security of IS [ISO 2009]. This assumes particular relevance in the attribution of blame and in the cases of disputes settled in court.

Safety

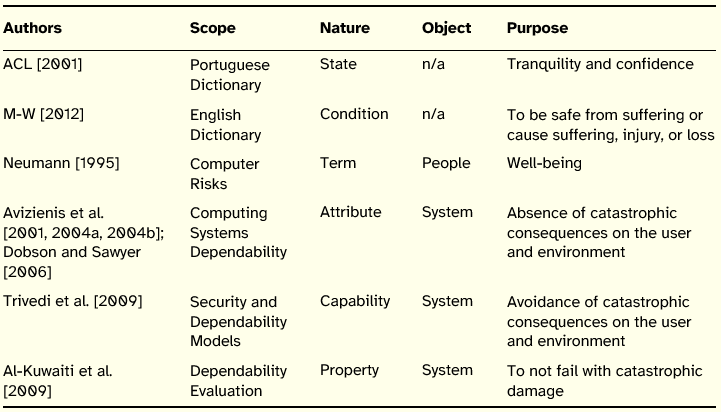

The concept of safety was found in the literature on dependability of systems. In the Portuguese dictionary, safety is presented as synonym of security [ACL 2001], corresponding to the absence of danger. The meaning advanced by the English dictionary is closer to the definitions proposed by systems dependability researchers, as showed in Table 9.

Table 9: Summary of Safety Definitions

In the definitions analyzed, safety is used in the realm of systems, and there is significant consensus regarding the purpose of this principle, namely the absence of catastrophic consequences on the environment and people. In centering the concept on the effects of system misbehavior, proponents classify consequences as catastrophic, circumscribing the concept to the situations where outcomes exceed a certain threshold (e.g., when human lives are in danger or are lost). Essentially, it is an ability or property of a system to not cause harm to environment and people.

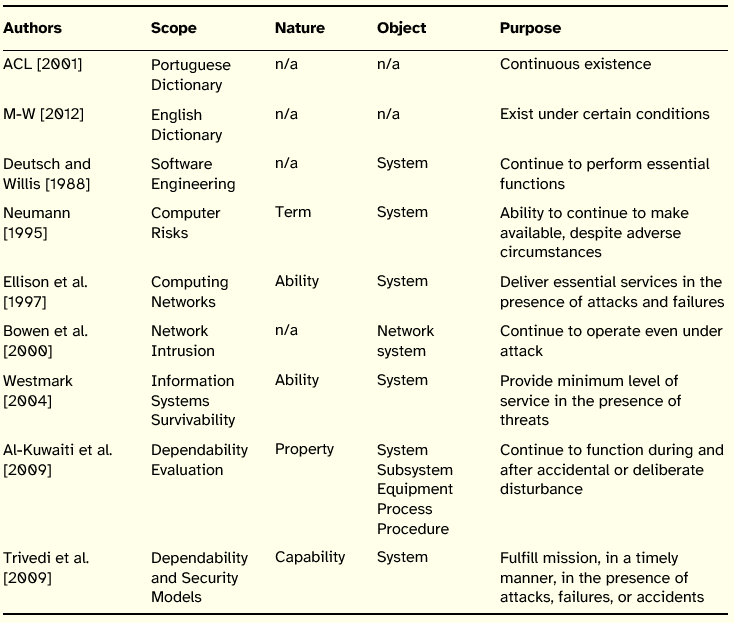

Survivability

As in the case of other concepts already reviewed, survivability is presented not as a principle applied directly to information, but applied to systems in general. Table 10 summarizes the review made on the concept of survivability.

Table 10: Summary of Survivability Definitions

As mentioned, the object focused by the definitions is the system (computers and networks). Concerning the nature, survivability is usually presented as a systems ability, whose purpose is to maintain operation even in the presence of failures or attacks. This principle is interrelated with the resilience trait of systems, understood as the capability to respond to and recover quickly from crisis situations. In order to survive, a system needs to adapt to the changing conditions of its environment (attacks, failures, and accidents) so that restoration of a minimum level of service is attainable.

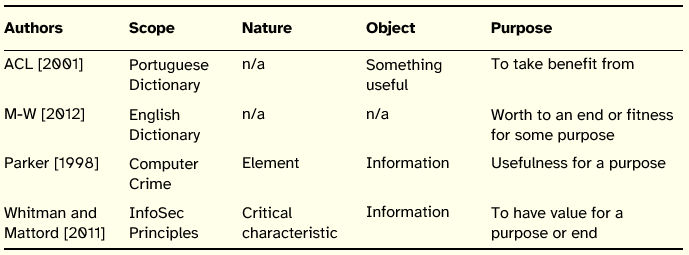

Utility

In the field of InfoSec, the principle of utility appears in the framework proposed by Parker [1998]. Table 11 summarizes the review made on the concept of utility.

Table 11: Summary of Utility Definitions

Parker articulates the principle of utility with the principle of availability, relating the first to usefulness of information and the second to usability of information. To illustrate the difference between those principles, Parker outlines a scenario where an employee that routinely encrypts the only copy of valuable information stored in his computer, accidently erases the encryption key of the file. In this case, the availability of information is maintained, but its usefulness is lost. In a way, Parker restricts availability to the preservation of access to information, separating its access from its use. If a user accesses information that is presented in a language he does not understand we will have a compromise of utility, although the information maintains its availability.

By indexing the utility of information to a specific purpose, Parker brings to the realm of InfoSec concerns about the degree of usefulness of information for the task users have in hand.

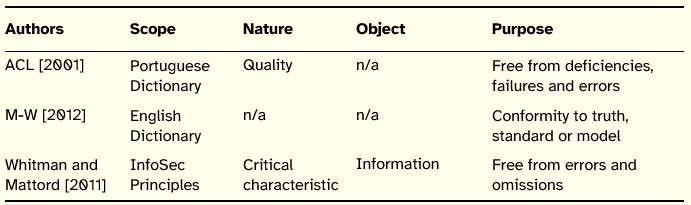

Accuracy

The concept of accuracy is used in many various contexts. In the field of InfoSec it was introduced by Whitman and Mattord [2011] in their expanded model of critical information characteristics. Table 12 summarizes the review made on this concept.

Table 12: Summary of Accuracy Definitions

Whitman and Mattord [2011] combine in the principle of information accuracy the freedom from mistakes and errors and the existence of the value that the end user expects, arguing that if information has been modified, intentionally or unintentionally, it is no longer accurate. At the first glance, this understanding approximates the definition of integrity. However, if we consider the examples provided by those authors we are able to clarify the meaning of accuracy. Whitman and Mattord [2011] illustrate the principle using a checking account example. An individual assumes that the information contained in the checking account is an accurate representation of his finances. Incorrect information in the checking account may result from external or internal errors. A bank teller may mistakenly add or subtract too much from the account, incorrectly changing the value of information. The account holder may accidently enter an incorrect amount in his account register. In contrast to the integrity definitions, both situations described for the checking account example differ from the fact that the agents (bank teller and account holder) are authorized to change the information, however, they modify it to an incorrect value.

Possession

The principle of possession of information is part of the InfoSec expanded model proposed by Parker (1998]. Whitman and Mattord [2011] have also included this principle in their InfoSec model. Table 13 summarizes the review made on the concept of possession.

Table 13: Summary of Possession Definitions

From these definitions, it is stressed the aspect of information control. Nowadays, it seems consensually accepted that ownership and control of information are perhaps the most important sources of power in organizations.

Parker [1998] justifies the addition of this principle to the traditional model so that InfoSec efforts may prevent certain types of losses, such as theft of information. The rational outlined by that author is clarified by contrasting between possession and confidentiality. By definition, the principle of possession deals only with what people possess and know, not what they possess without knowing. To illustrate this difference, Parker describes a scenario where burglars broke into a computer center and stole media containing the companys computer master files and the associated backup copies of the files. The gang held the materials for ransom. Confidentiality was not an issue because burglars had no reason to read or disclose the information contained in the files. The company lost possession of the files (availability was delayed, but the firm could retrieve the information at any time by paying the ransom). Increasingly, we own significant information that we, but that we own, such as object files.

Since it is usually extremely simple and cheap to produce additional copies of information, we may have different degrees of control regarding the information we own. This will be the case of having exclusive or shared possession of information, as well as being able to regain ownership after a temporary loss of possession.

2.3 Complements to the Triad

In this section we review four principles proposed by Dhillon and Backhouse [2000] that constitute a clear departure from the CIA triad. Instead of restricting their attention to information stored or in transit in silicon processors (computers and networks), those authors focused the security challenges placed and faced by biological processors of information (people). Consequently, this group of principles mainly focuses on the conduct and behavior of people in an organizational context that may have impact in the integrity of the organization as a whole, or in the security of information manipulation activities in particular. Thus, the four principles form a complement to the CIA triad instead of just extending the traditional model of InfoSec.

The four principles are known by the acronym RITE (Responsibility, Integrity, Trust, Ethicality) and they are defined below.

Responsibility—Contrasting to accountability, this principle refers to the responsibility that each member of an organization should observe when performing its function. With the disappearance of vertical management structures, a clear perception of personal responsibility and knowing what roles to play within the organization become increasingly important. The relevance of responsibility is more acute when new circumstances arise in the organization and it becomes necessary for someone to voluntarily assume the responsibility (even if it has not been assigned) to deal with these same circumstances. Otherwise, by not assuming the new responsibility the level of risk of the information system may increase and the integrity of the organization may be in jeopardy.

Integrity—In todays organizations information is one of the most valuable asset, however, it is an asset that by its nature may be easily divulged to unauthorized parties. In this respect personal integrity is of particular importance. Nevertheless, organizations do not always check the references of their future employees before granting them access to sensitive information, and even if they check, there is no warranty that a person maintains its integrity forever. Although the designation of this principle is the same as the one that composes the CIA triad, in this context integrity is connected to the loyalty of the members of the organization.

Trust

Ethicality—This principle advocates that members of an organization should adopt ethical behaviors even if these are not formally defined and implemented. It essentially deals with the informal relationships that are established within the organization and with behavior in the face of new situations for which there are simply no pre-defined rules on how to act or interpret.

2.4 Remarks on the Review

In this section we present a set of remarks on the literature reviewed and on the InfoSec principles that were identified and discussed.

The first remark is that InfoSec, currently, may still develop largely around the traditional principles of confidentiality, integrity, and availability. This situation is of particular concern when international standards, such as ISO/IEC 27000 family, especially ISO/IEC 27001 due to its role in certification, do not yet incorporate in their content explicit and accurate references to and concerns with additional InfoSec principles that are fundamental for dealing with the growing complexity of threats to the security of organizations information assets.

As it can be seen in the review presented, it is relatively easy to find scientific literature on the traditional principles of InfoSec, contrary to what is the case for other InfoSec principles.

Additionally, there were few authors who sought to expand the traditional CIA model, proposing new models or frameworks that include additional principles of InfoSec, with the works by Parker [1998], Dhillon and Backhouse [2000] and Whitman and Mattord [2011] being exceptions.

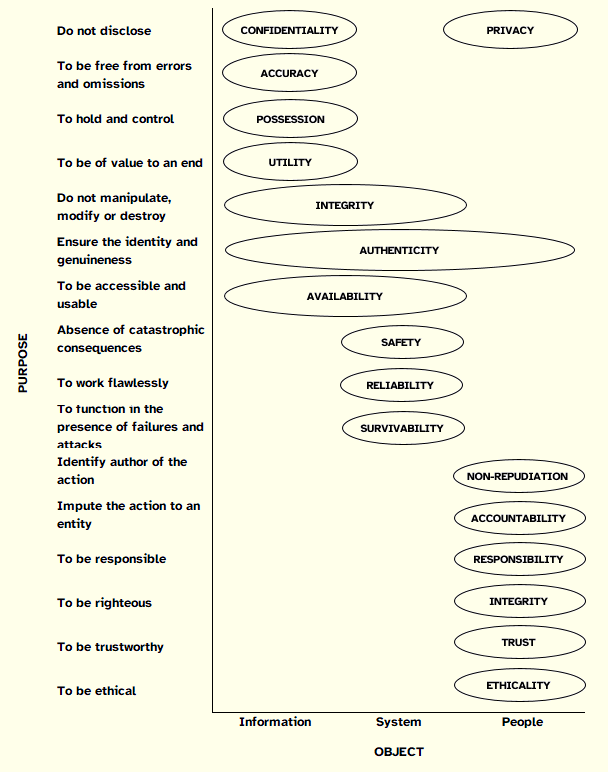

Regarding the principles of InfoSec that were identified, from the point of view of the focused object, they can be grouped into three major classes: focus on information, focus on systems, and focus on people.

In an attempt to synthesize the literature reviewed, we present in Figure 1 the results of crossing two of the elements analyzed in the definitions that we considered important to characterize and to distinguish each of the principles: the purpose and the object focused. Based on this diagram one can check the positioning of the principles in relation to those two axes, as well as the intersections or proximity that exist between principles.

Figure 1: Summary of Literature Reviewed

3. Relating InfoSec Threats to InfoSec Principles

In the field of InfoSec threats are a fundamental concept. Threats feed risk analysis exercises, concentrating the attention of security managers who project and implement controls aimed to mitigate the effects of threats turned into attacks. One way to connect threats and their potential impacts on information systems assets is by considering what InfoSec principles may be in jeopardy if threats materialize.

In order to get a better grasp of the InfoSec principles reviewed, and thus taking a further step towards the proposal of a revised framework of InfoSec principles, we crossed the principles to a battery of InfoSec threats. This exercise served as a test on the scope and completeness of the list of principles.

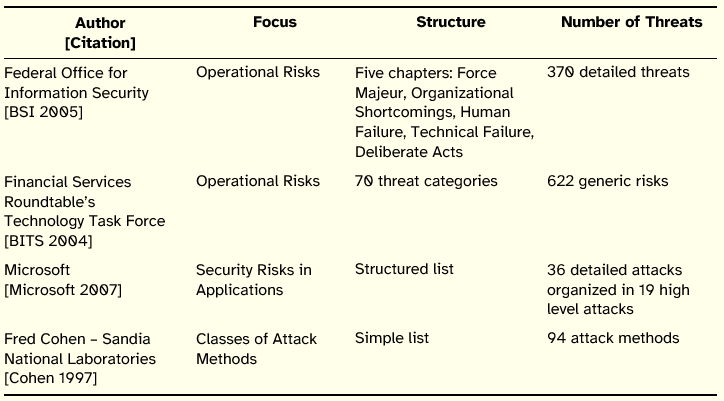

To operationalize this test we needed to instantiate the principles to a sufficiently broad and representative set of InfoSec threats. To this end we condensed a Unified Threat Catalog (UTC) that resulted from the fusion of four distinct threat and attack catalogs featured in Table 14.

Table 14: InfoSec Threat and Attack Catalogs

The option for condensing the four catalogs in a unified view, instead of simply applying one of the catalogs, was taken since we concluded that per se the original catalogs contained too general or too technical and detailed InfoSec threats and attacks. This would hinder the process of relating threats and attacks to the previously identified InfoSec principles. It was also considered that none of the catalogs alone was sufficiently complete and comprehensive to carry out the intended exercise. Thus, we decided to prepare a new catalog which resulted from the merger of the four catalogs mentioned above, taking as base the catalog issued by the German Federal Office for Information Security. Of the four catalogs, that one was considered the most comprehensive and complete and the one where, despite some exceptions, the threats and their respective descriptions are relatively straightforward to understand, not being too general or too detailed and technical.

The procedure for creating the UTC consisted of the following steps:

Identify threats duplicated in the catalogs, according to the descriptions provided, and join them, adopting the designation considered more direct and easy to understand;

Identify threats not present in the base catalog and include them in the UTC.

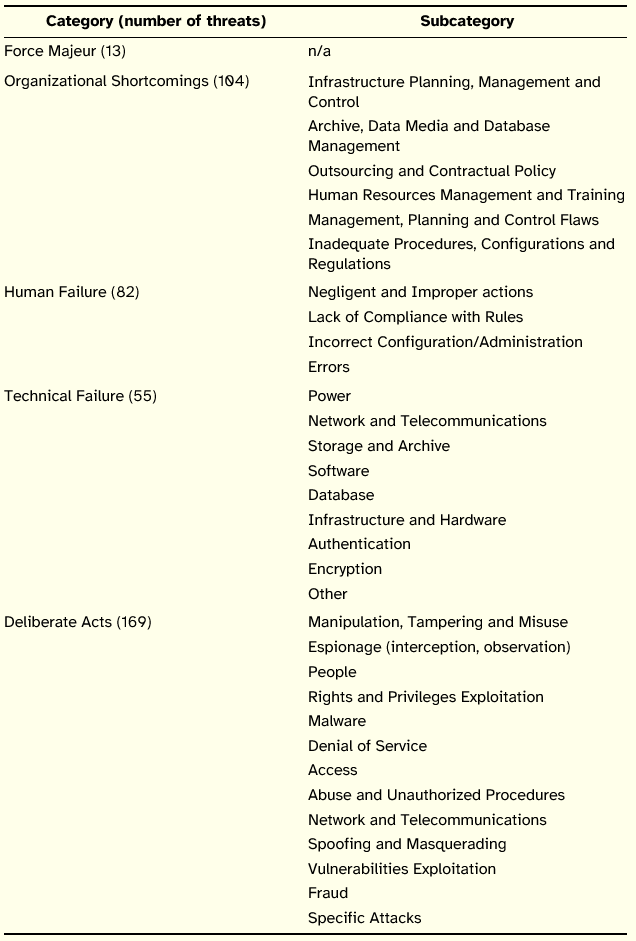

At the end we obtained a catalog composed of 422 threats organized into five categories and 32 subcategories, as presented in Table 15.

Table 15: Structure of the Unified Threat Catalog

The main categories were taken directly from the German catalog. The subcategories were introduced to allow a more logic organization of similar threats (from the point of view of its consequences on InfoSec principles) that were scattered and could complicate the analysis of the catalog.

The process of relating threats to principles consisted of, for each of the threats, identify the potentially affected principles. The intersection of the threats with the principles was based on the strict interpretation of the description of the threat in order to try to reduce the degree of subjectivity in the evaluation. In the case of threats with too general descriptions, whose attribution to specific InfoSec principles became unfeasible, we chose not to consider them, marking those threats as generic/general.

The outcomes of undertaking the process led to the formulation of four propositions.

Reinterpretation of Survivability Principle

Considering the definitions for the survivability principle, and taking into account that none of the UTC threats matched this principle, we reinterpreted this principle as a contributor to availability. In this view, survivability is perceived as an ability of a system to endure severe situations. The ability to withstand serious attacks and to be tolerant to failures is particularly important for systems comprising national critical information infrastructures and it has attracted much attention in the areas of cyber defense and SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems security.

Discard of Safety Principle

As defined by several authors, safety means the absence of catastrophic consequences on the environment caused by a given system. Safety may be considered as a general principle related to adverse situations, since it aims to preserve the environment outside a given system, information systems included. Furthermore, it was not possible to attribute any of the UTC threats to safety.

Proposal of Legality Principle

During the crossing process, it was found that some threats regarding legal consequences for the organization, and that could jeopardize InfoSec, could not be matched to any of the principles identified. Thereby, we propose the inclusion of a new principle, named legality, in order to address those particular threats.

We consider this principle particularly relevant in the present times, given the increased need for InfoSec professionals to ensure the compliance of information systems controls with several regulatory pieces [Berghel 2005].

Maintenance of RITE Principles

Analyzing the results of the crossing process, one notes that RITE principles have a reduced expression in terms of the number of threats that may impact those principles. At first, one could be led to discard these principles, but a finer consideration of the contents of UTC may suggest a different alternative. Indeed, the UTC resulted from the fusion of four catalogs, so it shares the qualities and shortcomings of those underlying catalogs.

We argue that one of the shortcomings of the UTC is its adherence to the traditional InfoSec principles, namely the CIA triad, leaving out other potential principles, especially those that complement confidentiality, integrity and availability, as is the case of RITE principles. Indeed, UTC and the base catalogs may suffer from a too restrictive focus on information stored in and in transit between IT systems. As Dhillon and Backhouse [2000] have noted, The traditional information security principles of confidentiality, integrity and availability are fine as far as they go, but they are very restricted. They apply most obviously to information seen as data held on computer systems where confidentiality is the prevention of unauthorized disclosure, integrity the prevention of the unauthorized modification, and availability the prevention of unauthorized withholding of data or resources. As the authors conclude, it is a common conception to apply the CIA triad at the technical level, but it is the human and social context that determines the success of InfoSec technical controls.

In order to find a more robust support for our claim regarding the UTC (and the originator catalogs), we undertook an additional analysis of the UTC, this time by relating its threats to the elements of Alters [1999, 2008] Work System Model (WSM). The goal of this process was to evaluate the degree of coverage of UTCs set of threats.

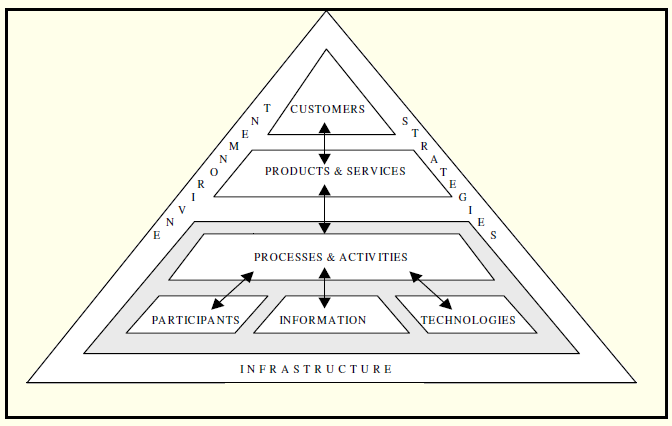

According to Alter [2008, p. 451], a work system is a system in which human participants and/or machines perform work (processes and activities) using information, technology, and other resources to produce specific products and/or services for specific internal or external customers. Alter views information systems as work systems, whose processes and activities are dedicated to capturing, transmitting, storing, retrieving, processing, and displaying information. In Figure 2 we present the architecture of the WSM.

Figure 2: Work System Model [Alter 2008, p. 461]

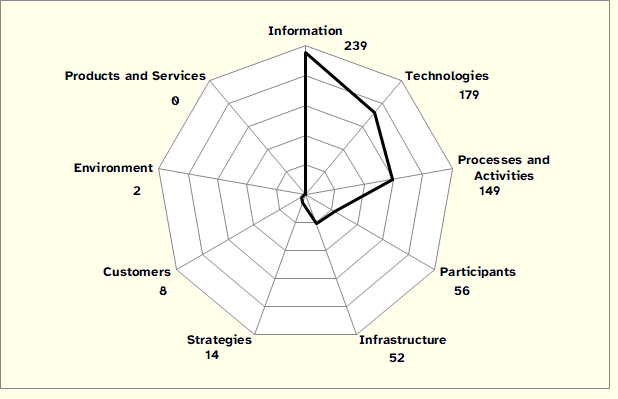

The process that we undertook to relate UTC and WSM was similar to the one applied to the crossing of UTC and InfoSec principles: based on the description of each threat, we determined which elements of the WSM would suffer the consequences of the threat. Figure 3 summarizes the results of this process of relating UTC and WSM. The three most affected elements of the WSM are Information, Technologies, and Processes and Activities.

Figure 3: Correspondence between UTC and WSM

It is evident that UTC threats do not uniformly cover all WSM elements, being concentrated on informational, technological, and functional aspects. Therefore, we argue there is a need to assess threats that may have an impact on elements such as Strategy, Environment, and Products and Services, but also to focus on information stored, communicated, and manipulated by biological processors, which are encapsulated in WSM Customers and Participants elements. According to WSM definitions, customers are people who benefit directly from the products and services produced by the work system. Participants include people who perform work in the business process, which may use IT extensively or residually, or that do not use IT at all.

It should be mentioned, however, that, as in the case of relating UTC threats to InfoSec principles, an effort was made to interpret narrowly and objectively the description of each of the threats, which helps to explain why WSM elements such as Products and Services, Environment, and Customers present very small values in what concerns the impacts of UTC threats. In a broader interpretation it would be logical to assume that threats that have an impact on Information, Technologies, and Processes and Activities may have direct consequences, for example, on Products and Services, and Customers in an organization.

4. Proposal of a Revised Framework of Information Security Principles

In this section we present the revised framework of InfoSec principles and briefly describe the processes that led to its creation.

The framework relies on the process of literature review that was conducted, in which we identified a set of concepts that, by their definitions and characteristics, were initially considered as InfoSec principles.

Subsequently, this initial set of principles was evaluated in terms of completeness and wholeness through its intersection with the UTC. The procedure adopted was to identify the principle or principles affected by each of the threats, thus seeking to ensure that the proposed framework would encompass all threats contained in the adopted catalog and assess the need to suggest new InfoSec principles due to unmatched threats to the initial set of principles. Additionally, we also related the UTC with the elements of the WSM. The two procedures helped us to draw broader conclusions regarding the preponderance of the proposed principles and elements of the WSM for InfoSec, providing additional robustness to the proposal and also allowing a different approach to the problem underlying this work.

The framework formulation process was iterative in nature, since over the course of it we needed to revisit and adjust the definitions that were initially assumed to be appropriate, as well as to review the structure and organization of the framework itself.

Next, we present the revised framework of InfoSec principles, followed by an exposition of a set of logical implications between the principles and a reappraisal of the relationship between the principles included in the framework and the UTC.

4.1 The Revised Framework

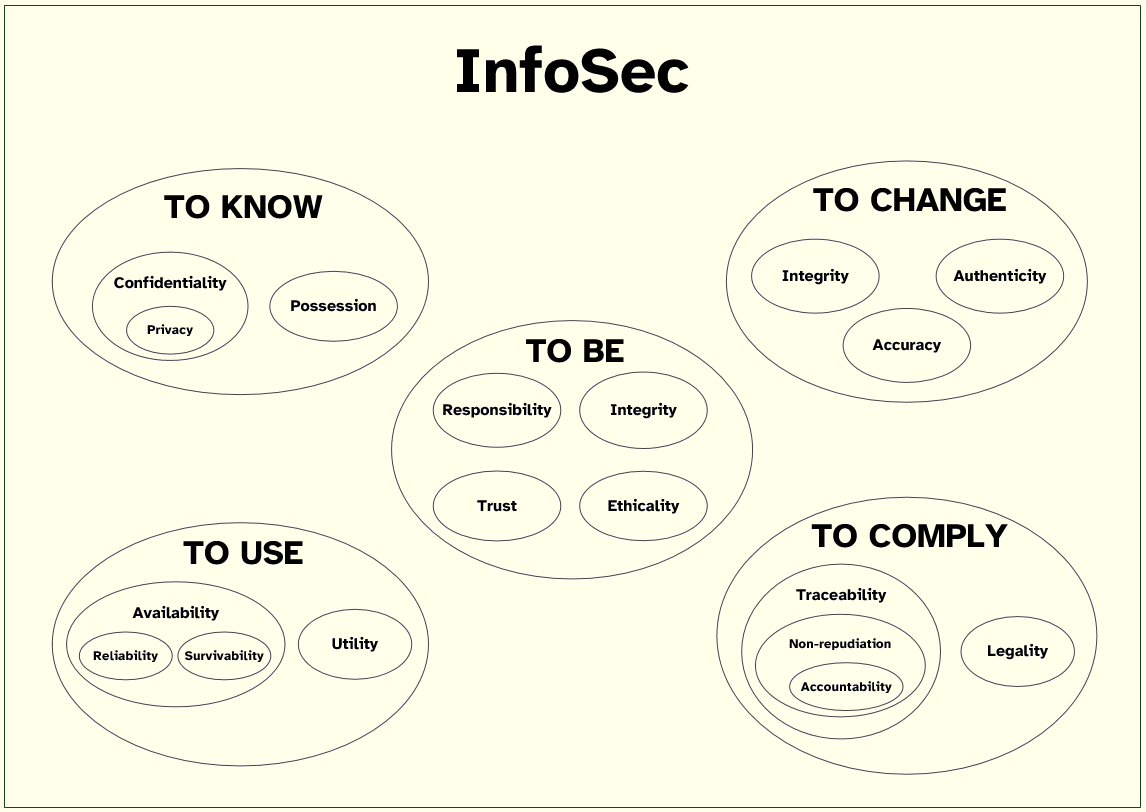

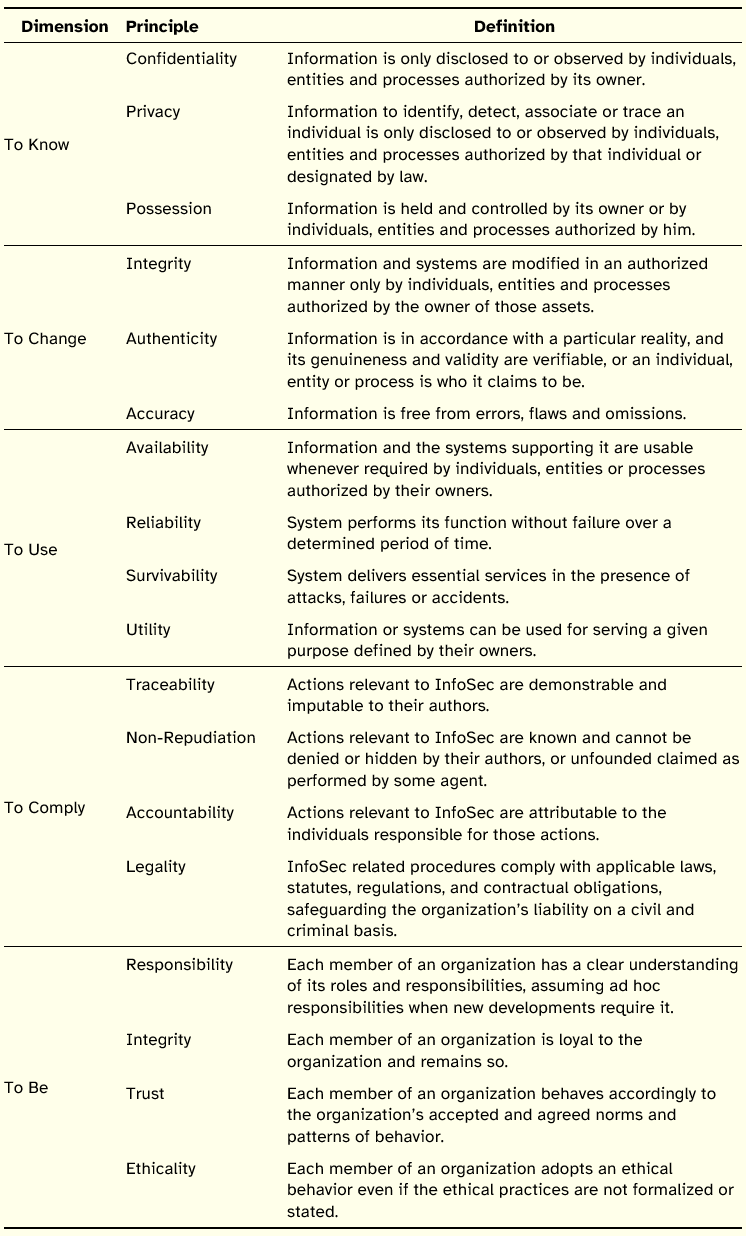

The proposed framework consists of thirteen principles and five sub-principles, organized as presented in Figure 4 and with the definitions adopted for each component enumerated in Table 16.

Figure 4: Proposed Framework of InfoSec Principles

The InfoSec principles were grouped into five distinct dimensions: To Know, To Change, To Use, To Comply, and To Be. This arrangement results from the main purpose of the principles pertaining to each dimension, i.e., inside each category, the constituent principles contribute to protect the same integrative issue.

Table 16: Adopted Definitions for Information Security Principles

The To Know dimension relates to the intrinsic value of information, i.e., its content and meaning. Privacy is presented as a sub-principle of confidentiality in that it refers exclusively to maintaining the confidentiality of specific information about people or their behavior, while the principle of confidentiality regards to all kinds of information. Hence, Privacy is conceived as a specialization or refinement of the principle of Confidentiality, although in certain contexts Privacy can, by itself, stand out.

In what concerns Possession, it is considered relevant to follow the perspective advanced by Parker [1998] according to which, the violation of this principle does not necessarily imply to not hold and to not control information as one might assume based on the definition presented. Information, being an intangible asset easily replicable, may be in possession of several entities. In this sense, a violation, for example, of the principle of confidentiality implies the violation of the exclusive possession of certain information. However, it is possible to have a situation of shared Possession where the owner of the information continues to own and control the information, simply does not do so exclusively. The principles and sub-principles that integrate this dimension essentially seek to prevent the disclosure to and observation of information by unauthorized entities, as well as control of information.

The second dimension, To Change, focuses primarily on actions that result in the modification and manipulation of information. The principles integrating this dimension seek to ensure that any modification of information is authorized by its owner, that is made only in an authorized manner, by individuals, entities, or processes whose identity is verifiable and that the information accurately reflects a certain reality.

It is important to clarify the meaning of the definition of the principle of Accuracy. In a first approach, one could consider Accuracy not as a principle, but as a sub-principle of Authenticity, since its definition meets the first part of the definition of Authenticity ”... accurately reflects a certain reality...”, however, and although it is recognized that there is some overlap between the two principles, the definition of accuracy focuses particularly on avoiding mistakes, failures, and omissions related to form and content. Illustrative examples are errors such as a misplaced comma in a numeric field, an extra zero or a missing zero, or typos. In this regard it is considered important to stress Accuracy of information as an InfoSec principle.

The third dimension To Use relates directly to the ability to use information or the systems that support and manipulate it. The observance of Availability, Reliability, Survivability, and Utility seeks to ensure that both information and systems that handle it are available for use by authorized entities, reliably, maintaining a sufficient degree of operation even after attack or failure, and whenever necessary.

Reliability is considered a sub-principle of Availability. Based on the definition adopted for Reliability, we consider that this concept is a prerequisite (though not exclusively) to the full observance of the principle of Availability, and therefore does not justify to be elevated to a principle by its own. A similar reasoning guided the decision of classifying Survivability as a sub-principle of Availability, pairing with Reliability.

Regarding the principle of Utility, a superficial analysis could lead to not consider this principle as an InfoSec principle, but as a general principle that information and systems must meet. Nevertheless, from an organizational point of view, especially from the point of view of information systems security management, Utility is particularly relevant as it does not matter to an organization to protect information or systems that are not useful to its activity, i.e., it does not make sense to apply human and financial resources to ensure the availability of useless information, possibly neglecting the protection of strategic information and systems for the organization.

The fourth dimension of the framework To Comply includes a set of principles and sub-principles which aims to address the need for controlling procedures in an organization, as well as ensuring technological and regulatory compliance of InfoSec efforts.

We propose the principle of Traceability as arising from the unification of the concepts of Accountability and Non-repudiation, in order to get a more complete and comprehensive principle. Therefore, the observance of the principle of Traceability and sub-principles Non-repudiation and Accountability ensures that any action relevant to InfoSec is provable, i.e., there are records of those actions, and that it can be unequivocally attributed to a specific individual, entity, or process.

The principle of Legality focuses on safeguarding negative impacts on InfoSec resulting from legislation and regulation inobservance and on safeguarding the organization itself in civil and criminal terms. In some countries like the USA there are, for example, restrictions on the use of encryption techniques that can make it impossible to use certain information and jeopardize its security. Furthermore, in the current globalized world, the knowledge, implementation, and compliance with InfoSec related legislation is particularly relevant. It should be noted that this principle was not identified in the literature reviewed, resulting from the process of relating InfoSec principles to InfoSec threats, and from the acknowledgment that regulatory aspects currently have a significant impact on InfoSec.

The fifth dimension To Be addresses what members of an organization must be within that organization in order to maintain the well-being and viability of the organization. The constituent principles focus on the behaviors that individuals should adopt, especially when faced with new and unforeseen situations for which there are not formalized rules or codes of practice. These principles are dependent upon the values, beliefs, and personal motivations of the organizations members, contributing to the establishment and maintenance of an InfoSec culture [Dhillon 2007]. This dimension has a principle (Integrity) whose designation is the same as the designation given to a principle pertaining to the To Change dimension. We chose to keep the designations that were in use by tradition or as named by its proponents. Nevertheless, the semantics associated to each of those principles is clearly distinct.

4.2 Relationships between Principles of the Framework

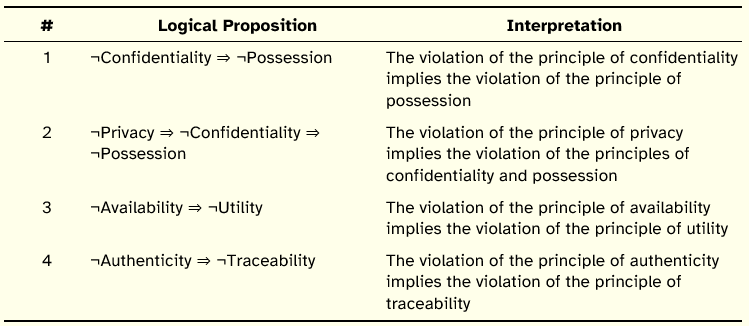

In this section we make explicit relationships between some of the principles that compose the revised framework, in the form of logical implication propositions. These propositions are exclusively supported and based on the definitions that were provided in Table 16. In Table 17 we show the logical propositions and the corresponding interpretation in natural language.

Table 17: Relationships of Logical Implication between Principles of Information Security

Regarding the first proposition it is logical to assume that a breach of confidentiality will, perforce, imply a breach of possession. However, the inverse proposition does not hold, i.e., a breach of possession does not necessarily imply a breach of confidentiality. For example, in the case of negligent or accidental deletion of confidential information there is a breach of the principle of possession, in the sense that information is no longer owned and controlled, but there is no disclosure of information to unauthorized entities, the information simply ceased to exist. Analyzing this proposition, not under the perspective of the violation of the principles, but under the perspective of its preservation, one can then infer that the preservation of possession implies the preservation of confidentiality. As an illustrative example, if an individual or organization has the ownership (as per the definition given for possession) of a given information, that information will only cease being confidential if the owner so desires. It should be reminded that possession is here understood as exclusive possession.

The second proposition follows the same logic advanced for the first proposition, and derives from the fact that privacy is considered a sub-principle of confidentiality.

Regarding the third proposition, it is relevant to note that information or systems to be useful must necessarily be available when they are needed, otherwise there is a violation of the principle of utility, in the sense that if they are not available they cannot be used for a particular purpose.

However, the inverse proposition (¬Utility ⇒ ¬Availability) does not hold. For example, an organization may have at its disposal a large amount of information, therefore fully available, which does not serve its purpose, being useless information which there is no interest to protect. From the point of view of the preservation of the principles (instead of their violation) it follows that the preservation of utility implies the preservation of availability. In light of the definition given to utility, information will only be used if it is available.

In the fourth proposition we relate the principle of authenticity to the principle of traceability. The observance of the principle of traceability and consequently of its sub-principles, non-repudiation and accountability, presupposes the existence of authentic information in accordance with the definition advanced for authenticity. If this condition is not verified, e.g., if there is false information recorded about the identity of a user who manipulated certain information, the principle of traceability is violated since it is not possible to unambiguously determine who in fact manipulated the information. This is an interesting proposition because it relates principles pertaining to two different dimensions.

The implication relationships that were advanced are those that we assume as universal, i.e., verifiable in any context in the light of the proposed definitions. In certain contexts or particular cases it may be possible to infer other logical propositions.

4.3 Revisiting the Relationship between InfoSec Threats and InfoSec Principles

The proposed framework of InfoSec principles combines a set of definitions for the constituent principles with a structuration of the principles. These two features of the framework justify revisiting the previously established relationships between InfoSec threats, based on the UTC, and the InfoSec principles. The analysis of the relationships provides a holistic and quantitative view of the relations between InfoSec threats and the InfoSec principles as proposed in the framework.

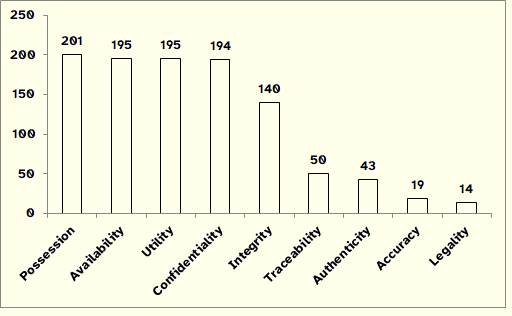

Figure 5 displays the InfoSec principles with the highest number of matches with the UTC threats.

The results reflect the implication relationships described in Section 4.2, with the principles of Possession, Availability, Utility, Confidentiality and Integrity being the most affected. However, this does not mean that we can overlook or underestimate the threats to the remaining principles since we argue that information security depends on the observance of the framework as a whole.

It is also pertinent to mention that the threat catalogs that led to the UTC generally follow the traditional CIA model, which helps to explain the prevalence of threats on the traditional InfoSec principles (the results obtained for Possession and Utility, which are not part of the traditional model, derive from the logical implication propositions exposed in Section 4.2).

Figure 5: Number of Matches UTC vs. InfoSec Principles

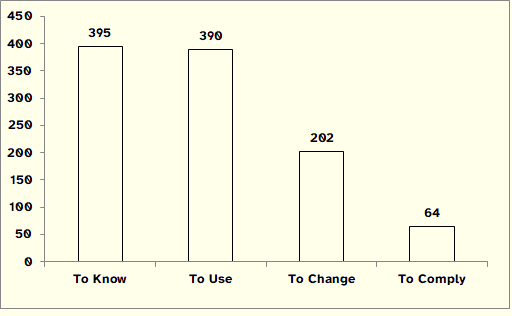

Another perspective is provided by the analysis of results obtained for the dimensions that constitute the revised framework, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Number of Matches UTC by Dimension

The dimension To Know, constituted by the principles of Confidentiality and Possession, and by the sub-principle of Privacy, and the dimension To Use, constituted by the principles of Availability and Utility, and by the sub-principles Reliability and Survivability, are those that condense a greater number of matches.

We argue that the absence of matches with the principles of the To Be dimension should not prompt the removal of the corresponding principles or be interpreted as a sign of subsidiarity of those principles in relation to all the other principles. The common view in InfoSec points people as the weakest link of the InfoSec protection efforts, thus implying that a special consideration of the role of people should be taken into consideration. As a complement to that view, we argue that people is also the strongest link of the InfoSec protection efforts: not only the quality and appropriateness of security controls are a function of the individuals that design, implement, interpret, and maintain those controls, but also the members of the organization form the last line of defense against threats not addressed or only partially covered by technical safeguards. Instead of discarding the To Be principles, we urge to the development of an encompassing catalog of threats that takes into account the personal and social dimensions of InfoSec.

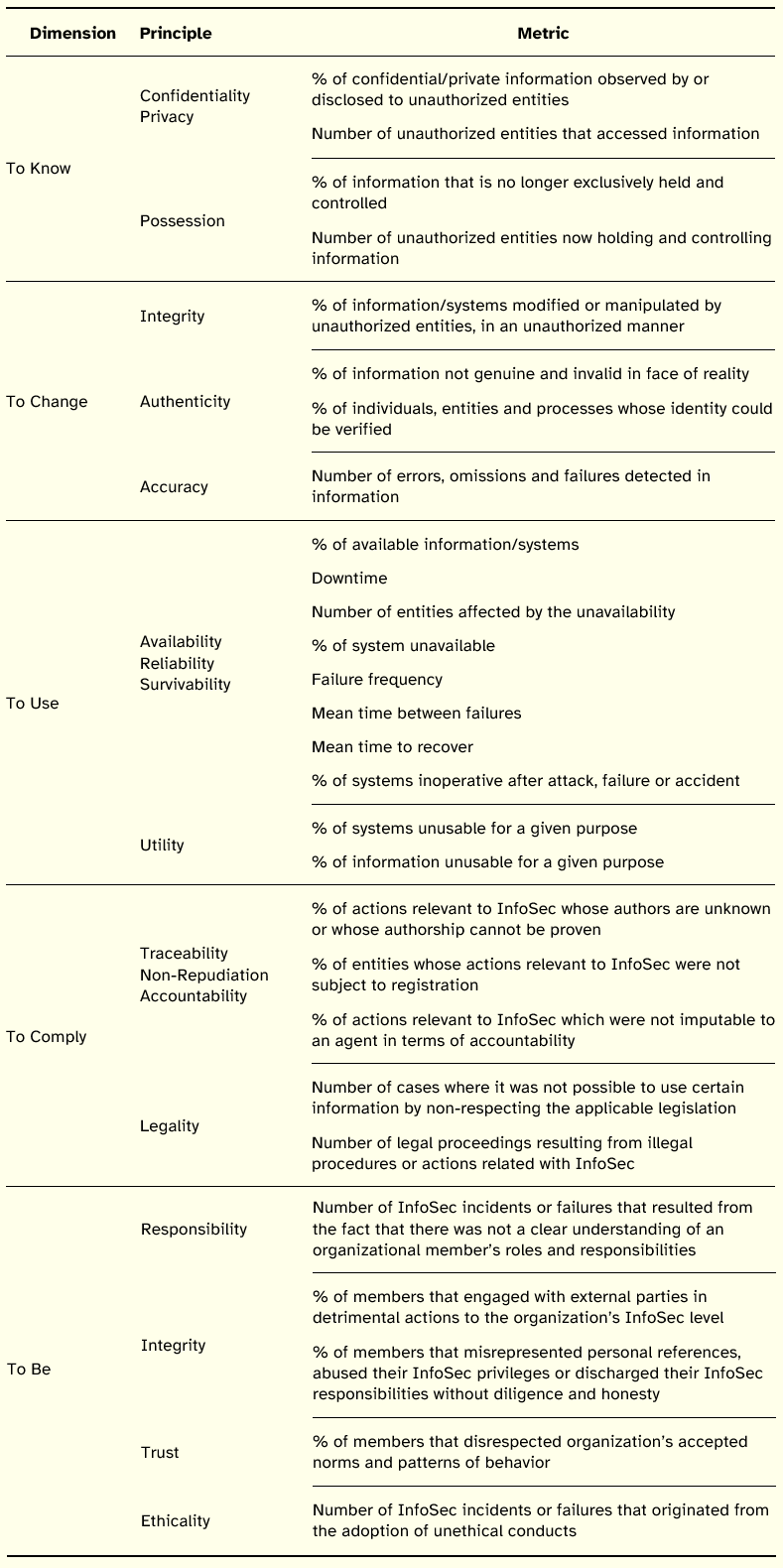

5. Metrics for the Information Security Principles

After presenting the revised framework of InfoSec principles, we are now in position to address the issue of measurement. In this section we suggest for each principle metrics that may assist, in case of attack or failure, to assess the extent to which that principle was compromised.

It should be noted from the beginning that the suggested metrics are purely conceptual resulting directly from the definitions adopted for each of the InfoSec principles and lacking tests in real environments. Basically, it is an initial effort to mitigate the gaps identified in the literature on InfoSec metrics, and to assign measures directly to the InfoSec principles.

Research on InfoSec metrics is relatively recent and there are no consolidated references widely accepted by the scientific community, InfoSec professionals and managers to assess the level of InfoSec of an organization [Pfleeger 2009].

The inexistence of measurement references accrue from several factors, including the difficulty of measuring InfoSec [Pfleeger and Cunningham 2010]; dependence on subjective, human and qualitative inputs, illusory means to obtain measurements; lack of understanding of information security mechanisms [Jansen 2011], immaturity of research efforts and fragmentation of the knowledge areas that need to combine efforts to produce a holistic model for InfoSec measurement [Savola 2007]. This does not mean, however, the absence of important contributions for InfoSec evaluation over time, such as TCSEC, SSE-CMM (Systems Security Engineering Capability Maturity Model), and Common Criteria, as well as proposals of high level taxonomies for InfoSec metrics (cf. Chew et al. [2008], CISWG [2005], Savola [2007], Seddigh et al. [2004]).

Besides these contributions, NIST and ISO have produced two major works regarding InfoSec metrics, namely NIST SP 800-55 Rev. 1 and ISO/IEC 27004, which provide guidelines for the development, selection and implementation of InfoSec measures. These documents include illustrative and candidate InfoSec measures to evaluate the effectiveness and quality of organizations information security protection efforts. This stated purpose for evaluation is consistent with several definitions of InfoSec metrics, such as quantitative measurements of trust indicating how well a system meets the security requirements [Wang 2005] and measurable standards to monitor the effectiveness of goals and objectives established for IT security [Patriciu et al. 2006].

According to Wang [2005], the InfoSec metrics that have been developed suffer from five limitations: security metrics are often qualitative rather than quantitative, subjective rather than objective, defined without a formal model as an underlined support, there is no time aspect associated with the current security metric definitions, and traditional two-value logics are not suitable for security analysis.

To counteract this state of affairs regarding InfoSec measures, Jaquith [2007] and Jansen [2011] proposed several characteristics that metrics should show in order to be useful, effective, and objective. Among the characteristics that metrics should have are the following: to be consistently measured, to have a low cost of implementation, to be expressed numerically or as a percentage, to use a unit of measurement, and to be relevant for those who are going to analyze them.

With these features in mind, and aiming to evaluate the extension of compromise of the InfoSec principles, we propose the basic set of metrics listed in Table 18.

Table 18: Metrics for Information Security Principles

As noted, the metrics flow directly from the definitions that were adopted for the InfoSec principles and form a first iteration to achieve a set of metrics that shows the ideal characteristics previously enumerated. In future versions, more sophisticated formulations of the metrics should take into account issues such as the value of information affected, the criticality of systems impaired, the costs of the incident, and the effect of time.

Two of the main features of the set of proposed metrics are its simplicity and ex post nature. The metrics are simple to understand and to quantify, although some require the collection of based data and the establishment of the corresponding data collection structures [e.g., to measure confidentiality related breaches it is needed to previously perform an information inventory, to classify information and to define the entities authorized to access information). They are also a posteriori or ex post measures, i.e., they focus on after the fact events, since they provide indications regarding compromise of InfoSec principles. This implies that the accuracy of the measures is totally dependent on the detection capabilities of the organization: if a breach is not known or acknowledged by the organization, the respective measure will not reflect it.

In contrast to other InfoSec proposed measures, such as the ones advanced in NIST SP 800-55 Rev. 1, the suggested set of metrics does not provide an indication of the estimated quality and efficacy of InfoSec protection efforts. Actually, it complements those kinds of measures. Instead of measuring the budget devoted to information security, the percentage of high vulnerabilities mitigated within organizationally defined time periods after discovery, the percentage of security personnel that have received security training, or the percentage of systems that have conducted annual contingency plan testing, it gives evidence of the actual effectiveness of InfoSec protection efforts. An important future line of research would be to define an alternative set of metrics, directly connected to the InfoSec principles, that instead of assessing the extent to which each of the principles has been compromised, indicates how well a particular security control contributes to the preservation of those principles.

6. Conclusion

The growing dependence of organizations on information and IT justifies the existence of updated references that assist organizations to protect their informational assets. Over time, several authors have argued for an update group of principles that may guide the information security efforts of organizations, both by reviewing the meanings of current principles, and by suggesting additional principles that help InfoSec stakeholders to keep up with the evolution of business requirements, threats, and technology.

In view of this continual need to reconsider the foundations that define information security, we proposed a revised framework of information security principles structured in five dimensions containing thirteen principles and five sub-principles. Each of the components of the framework was defined and supplemented with a basic and initial set of metrics.

We hope that these contributions may prove useful for the management of information security in organizations, assisting its stakeholders to engage in a dialogue regarding the goals of information protection and the means that best accomplish the attainment of an appropriate information security level.

The proposed framework of information security principles is not final and should be open to debate and revision. It is our expectation that it may prompt the development of an updated catalog of information security threats closely related or rooted in those principles, as well as the emergence of new insights regarding more mature and sophisticated InfoSec effectiveness metrics.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by FEDER funds through Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade—COMPETE and National funds by FCT—Fundao para a Cincia e Tecnologia under Project FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-022674.

References

ACL (2001). Dicionário da Lingua Portuguesa Contemporânea da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Lisboa: Verbo.

Al-Kuwaiti, M., N. Kyriakopoulos and S. Hussein(2009). A comparative analysis of network dependability, fault-tolerance, reliability, security, and survivability. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 11(2), 106–124.

Alter, S. (1999). A general, yet useful theory of information systems. Communications of the AIS 1 (3es). 3

Alter, S. (2008). Defining information systems as work systems: implications for the IS field. European Journal of Information Systems 17(5), 448–469.

Avizienis, A., J.-C. Laprie and B. Randell (2001). Fundamental Concepts of Dependability. Department of Computing Science Technical Report Series.

Avizienis, A., J.-C. Laprie and B. Randell (2004a). Dependability and its Threats: A taxonomy. 18th IFIP World Computer Congress.

Avizienis, A., J.-C. Laprie, B. Randell and C. Landwehr (2004b). Basic concepts and taxonomy of dependable and secure computing. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 1(1), 11–33.

Berghel, H. (2005). The Two Sides of ROI: Return on Investment vs. Risk of Icarceration. Communications of the ACM 48(4), 15–20.

BITS (2004). Kalculator: Bits Key Risk Measurement Tool For Information Security Operational Risks. http://www.bits.org/publications/doc/BITSKalcManage0704.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2013

Bowen, P., J. Hash and M. Wilson (2006). NIST SP 800-100: Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers. NIST Special Publication.

Bowen, T/, D. Chee, M. Segal, R. Sekar, T. Shanbhag and P. Uppuluri (2000). Building survivable systems: an integrated approach based on intrusion detection and damage containment. Proceedings DARPA Information Survivability Conference and Exposition—DISCEX00, 84–99.

BSI (2005). BSI: IT-Grundschutz Catalogues. Federal Office for Information Security. https://www.bsi.bund.de/EN/Topics/ITGrundschutz/ITGrundschutzCatalogues/itgrundschutzcatalogues_node.html (Accessed 24 Jan 2013)

Chew, E., M. Swanson, K. M. Stine, N. Bartol, A. Brown and W. Robinson (2008). NIST SP 800-55 Rev. 1.: Performance Measurement Guide for Information Security. http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-55-Rev1/SP800-55-rev1.pdf (Accessed 7 Apr 2013)

Clarke, R. (2006). Whats Privacy? http://www.rogerclarke.com/DV/Privacy.html (Accessed 8 Jan 2013)

Cohen, F. (1997). Information system attacks: A preliminary classification scheme. Computers & Security 16(1), 29–46.

Cole, E. (2009). Network Security Bible. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing.

CISWG (2005). Report of the best practices and metrics team. Corporate Information Security Working Group. http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/CSD3661.pdf (Accessed 18 Apr 2013)

Deutsch, M. S. and R. R. Willis (1988). Software Quality Engineering: A Total Technical and Management Approach. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Dhillon, G. (2007). Principles of Information Systems Security: Text and Cases. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Dhillon, G. and J. Backhouse (2000). Information system security management in the new millennium. Communications of the ACM 43(7), 125–128.

Dobson, G. and P. Sawyer (2006). Revisiting Ontology-Based Requirements Engineering in the age of the Semantic Web. Dependable Requirements Engineering of Computerised Systems at NPPs. Halden: Institute for Energy Technology (IFE).

DoD (2002). Department of Defense Directive Number 8500.01E. USA Department of Defense.

EC (1991). Information Technology Security Evaluation Criteria (ITSEC). Publications of the European Communities, Brussels: ECSC-EEC-EAEC.

Ellison, R. J., D. Fisher, R. C. Linger, H. F. Lipson, T. Longstaff and N. Mead (1997). Survivable Network Systems: An Emerging Discipline. Technical Report, CMU/SEI-97-TR-013, ESC-TR-97-013.

ISO/IEC (2005). ISO/IEC 27001—Information technology Security techniques—Information security management systems Requirements. International Organiza-tion for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

ISO/IEC (2009). ISO/IEC 27000—Information technology Security techniques—Information security management systems—Overview and vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

ISSA (2004). Generally Accepted Information Security Principles (GAISP). http://all.net/books/standards/GAISP-v30.pdf (Accessed 6 Dec 2012)

ITGI (2007). COBIT 4.1—Framework, Control Objectives, Management Guidelines, Maturity Models. Rolling Meadows: IT Governance Institute.

Jansen, W. (2011). Research Directions in Security Metrics. Journal of Information System Security 7(1), 3–22.

Jaquith, A. (2007). Security Metrics: Replacing Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt. Upper Saddle River: Addison-Wesley.

Lategan, F. A. and M. S. Olivier (2000). Enforcing Privacy by Withholding Private Information. Proceedings of the IFIP TC11 Fifteenth Annual Working Conference on Information Security for Global Information Infrastructures, 412–430. Kluwer.

Lazzaroni, M., V. Piuri and C. Maziero (2010). Computer security aspects in industrial instrumentation and measurements. Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Technology Conference, 1216–1221.

M-W (2012). Merriam-Webster Dictionary and Thesaurus. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary

Microsoft (2007). Microsoft Threat Analysis & Modeling v2.1.2. http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=14719 (Accessed 9 Mar 2013)

Neumann, P. G. (1995). Computer Related Risks. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Parker, D. B. (1998). Fighting Computer Crime: A New Framework for Protecting Information. New York: J. Wiley.

Patriciu, V.-V., I. Priescu and S. Nicolaescu (2006). Security metrics for enterprise information systems. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 151–159.

Pfitzmann, A. and M. Hansen (2010). A terminology for talking about privacy by data minimization: Anonymity, Unlinkability, Undetectability, Unobservability, Pseudonymity, and Identity Management. http://www.elopio.net/sites/default/files/Anon_Terminology_v0.34.pdf (Accessed 25 Feb 2013)

Pfleeger, C. P. and S. L. Pfleeger (2003). Security in Computing. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Pfleeger, S. L. (2009). Useful Cybersecurity Metrics. IT Professional 11(3), 38–45.

Pfleeger, S. L. and R. K. Cunningham. Why Measuring Security Is Hard. IEEE Security & Privacy Magazine 8(4), 46–54.

Posthumus, S. and R. von Solms (2004). A framework for the governance of information security. Computers & Security 23(8), 638–646.

Prosser, W. L. (1960). Privacy. California Law Review 48(3), 383–423.

Rannenberg, K. (1993). Recent Development in Information Technology Security Evaluation—The Need for Evaluation Criteria for Multilateral Security. Proceedings of the IFIP TC9/WG 9.6 Working Conference, 113–128.

Savola, R. (2007). Towards a Security Metrics Taxonomy for the Information and Communication Technology Industry. International Conference on Software Engineering Advances (ICSEA 2007).

Seddigh, N., P. Pieda, A. Matrawy, B. Nandy, J. Lambadaris and A. Hatfield (2004). Current trends and advances in information assurance metrics. Proceedings of PST2004: The Second Annual Conference on Privacy, Security, and Trust, 197–205. New Brunswick.

Stamp, M. (2006). Information Security: Principles and Practice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Stewart, J. M., E. Tittel and M. Chapple (2011). CISSP: Certified Information Systems Security Professional Study Guide. Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing.

Stoneburner, G., C. Hayden and A. Feringa (2004). NIST SP 800-27 Rev A—Engineering Principles for Information Technology Security (A Baseline for Achieving Security), Revision A. NIST Special Publication. http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/PubsSPs.html (Accessed 4 Jan 2013)

Trivedi, K. S., D. S. Kim, A. Roy and D. Medhi (2009). Dependability and security models. Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop on Design of Reliable Communication Networks, 11–20.

Wang, A. J. A. (2005). Information security models and metrics. Proceedings of the 43rd Annual ACM Southeast Regional Conference—ACMSE.

Westin, A. F. (1970). Privacy and Freedom. London: Bodley Head.

Westmark, V. R. (2004). A definition for information system survivability. Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Whitman, M. E. and H. J. Mattord (2010). Management of Information Security. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Whitman, M. E. and H. J. Mattord (2011). Principles of Information Security. Boston: Cengage Learning.