Original source publication: Palas Nogueira, J. and F. de Sá-Soares (2012). Trust in e-Voting Systems: A Case Study. In H. Rahman, A. Mesquita, I. Ramos and B. Pernici (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems MCIS 2012—Knowledge and Technologies in Innovative Information Systems, 51–6. Guimarães (Portugal). Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, Volume 129, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, ISBN: 978-3-642-33243-2.

The final publication is available here.

Trust in e-Voting Systems: A Case Study

University of Minho, Centre ALGORITMI, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

The act of voting is one of the most representative of Democracy, being widely recognized as a fundamental right of citizens. The method of voting has been the subject of many studies and improvements over time. The introduction of electronic voting or e-voting demands the fulfillment of several requirements in order to maintain the security levels of the paper ballot method and the degree of trust people place in the voting process. The ability to meet those requirements has been called into question by several authors. This exploratory research aims to identify what factors influence voters’ confidence in e-voting systems. A case study was conducted in an organization where such a system has been used in several elections. A total of 51 e-voters were interviewed. The factors that were found are presented and discussed, and proposals for future work are suggested.

Keywords: e-Voting; Trust, Electronic Voting Systems; e-Voting Requirements

1. Introduction

The act of voting is a key part in democracy and one of its cardinal rights. The evolution that occurred in the voting process over times enables present day free elections to be framed in a well defined set of stages and requirements, which when properly implemented and enforced confer the fundamental characteristics of credibility and trust to all involved in the election—promoters, developers, electoral commissions, auditors, and most importantly, candidates and voters.

The method of voting has undergone changes in the various stages that make up its life cycle in order to improve its speed, security, flexibility, availability, and cost, especially during the authentication of the voter, the casting of the vote, and the tabulation stages.

As illustrations of the improvements implemented over time, there is the use of paper ballots, the development of specific legislation to streamline the voting process, and the introduction of mechanical means that made the process faster. In the recent past, we have witnessed the introduction of information technologies (IT) in the voting process, not without ups and downs along the way, seeking the transformation of the traditional voting system (paper ballot) in an electronic voting system.

However, the introduction of these technological elements in the elections has not been easy or consensual, especially with regard to the suspicions that they raise, their ability to meet the requirements that made paper ballot method trustworthy, and to a set of new questions concerning basic values like the anonymity of the vote and the accuracy of the system.

IT systems are currently used in many sensitive areas of society, such as for processing personal data, clinical data, or financial transactions. However, it seems these areas gather a greater consensus and apparently greater confidence on the use of IT by those involved than the introduction of these same technologies in the voting process.

In fact, electronic voting systems (EVS) are not yet widely used in elections of greater relevance and we observe countries moving forward and backward in implementing EVS for national elections: while some countries are already using EVS for several years, others banned its use. Between these extremes, there are cases of success and failure in the use of EVS [Dill et al. 2003; Granneman 2003; Mercuri 2001; Schneier 2004a; Schneier 2004b; Schneier 2006].

Among the various aspects that may facilitate or inhibit the success of EVS, trust has been recognized as a key factor [Antoniou et al. 2007; Grove 2004]. Along the quest for a completely trustworthy e-voting system—one that does not lose, add, alter, disregard, or disclose ballots—there is also the need to ensure that voting stakeholders also trust the system really has those properties [Randell and Ryan 2006].

The ability to demonstrate that EVS are trustworthy has a direct impact in the legitimacy and acceptance of the voting results, and it may be considered a prerequisite for shifting from the traditional voting systems to the voting systems on the Internet. Indeed, the integral acceptance of EVS must encompass all of society, including all voters and not just those who are predisposed to use them. If there is a large number of voters skeptical about this method of voting, trust in democracy may be compromised [Jones 2000; Schneier 2006].

The relevance of trust in e-voting may also be appreciated if one considers the potential goals of a deliberate attack launched against EVS, namely to produce an incorrect tabulation of votes, to prevent electors to cast their votes, to raise doubts about the legitimacy of the results of the election, to delay the promulgation of the results, and to violate the anonymity of the vote [McDaniel et al. 2007]. The possibility of any of these goals being achieved or the actual verification of their satisfaction casts a shadow of doubt among the electorate, severely affecting their confidence in those systems.

The belief that trust plays a major role in the adoption and acceptance of EVS as innovative technological systems with social impact motivated the execution of this work. Knowing what instills confidence into electors regarding the use of EVS will help to understand voters’ attitude towards e-voting and to devise better ways to design and deploy these systems.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify what factors influence voters’ trust in EVS.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Voting Systems

The voting systems are the means used by people who have the right to vote (the voters) to freely choose between different options.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the elections were conducted without much control and privacy [Jones 2001]. Everybody swore before a judge to be entitled to vote and having not already done, and the act of voting was exercised verbally, which means that a trust relationship was established between the voters and those who led the election (the judges). It was by then that were laid the foundations of the now widely accepted voting system.

Worldwide, the most used and accepted voting system is the paper ballot voting system (PBVS). Briefly, the voter attends in person (with some exceptions referred to in the legislation) and makes a mark in his or her choice of vote on paper and puts it in a ballot. At the end of the period stipulated for the voting process, the votes cast in the ballot are manually counted.

This voting system is mature and has been used innumerous times, which gives it a high degree of confidence for all to see. However, it still has certain limitations, both in terms of assuring the satisfaction of certain requirements (e.g., ensure that only those registered may vote or that the content of the vote is not eliminated during or after the voting period) and when compared to other voting systems (e.g., the delay and potential errors in the manual counting of the votes or the mandatory presence of voters in pre-established places in order to vote). Therefore, it is not surprising that other alternatives to the traditional system of voting have emerged, such as EVS.

Electronic voting or e-voting is a voting system that uses in any of its phases electronic means to assist the voting process. In the context of e-voting we may consider two main voting systems: poll-site electronic voting systems (PEVS) and remote electronic voting systems (REVS). The former, as in PBVS, implies the presence of the elector to vote in a pre-defined and controlled place by the electoral commission. The latter does not imply the presence of the voter in a previously defined place: the vote can be cast anywhere using the Internet as a medium of communication between the system and the voter. This study focuses on this type of electronic voting systems.

Regardless of the voting system used, in order to have quality and to transmit the necessary confidence to those involved in the voting process, the voting system will have to satisfy a set of requirements.

2.2 Requirements of Voting Systems

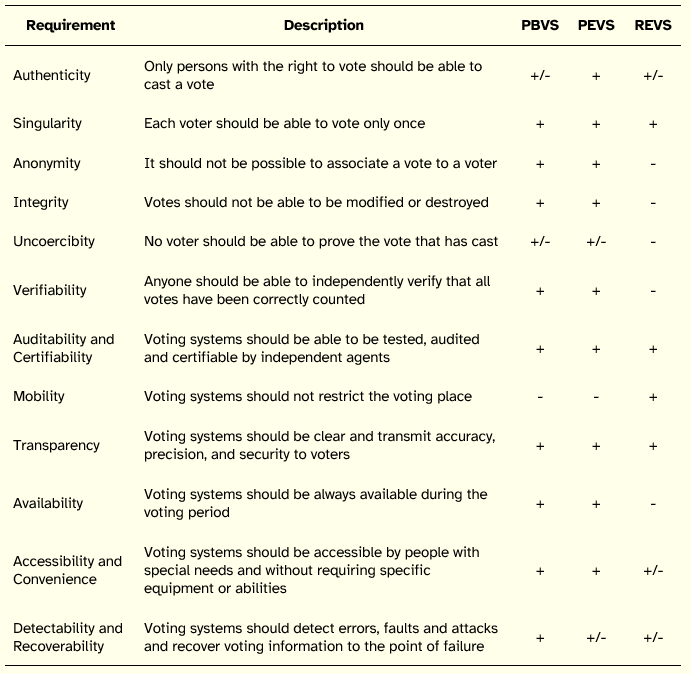

The literature review enabled the identification of a set of 12 core requirements against which voting systems should be analyzed and evaluated in order to judge their adequacy [ACE 2001; Antunes 2008; CE 2004; Crane et al. 2004; Cranor and Cytron 1997; Frith 2007; Gritzalis 2002; Hall 2008; Jones 2000; Mercuri 2000; Monteiro et al. 2001; Neumann 1993; Shamos 1993; Strauss et al. 2005].

Table 1 presents those requirements. The order in which requirements are listed intends to signal the importance that researchers have attributed to each one of the requirements, from the most important to the least important, based on the survey of the literature. The table is divided into five columns: the first includes the designation of the requirement, the second briefly describes it and the remaining columns provide a classification of the three voting systems considered in terms of requirements satisfaction. In these last three columns, a + sign indicates that the system generally satisfies the requirement, a - sign indicates that the system falls short of meeting the requirement, and a +/- sign indicates that currently the system does not meet the requirement, but may meet it in the short term.

Table 1: Relationship between Voting Requirements and Voting Systems

None of the voting systems satisfies all requirements, with systems that best meet certain requirements falling short of meeting other requirements.

2.3 Trust and Voting

In the realm of voting systems, trust may be conceived as the certainty, held by all electoral stakeholders, that the whole process takes place observing the desired assumptions, specifically with regard to the requirements that voting systems must meet, thus attesting the quality of the system and ensuring compliance with security parameters [Hall 2008].

If there is no trust by the stakeholders of a voting process, a voting system will hardly succeed and any suspicion that falls on the system precipitates its discredit and may jeopardize the elections. Indeed, several cases of misconduct in EVS led to a significant decrease of citizens’ trust on e-voting [Neumann 2004]. The literature provides details about several of those cases. A set of illustrative examples follows. In 1993, during the trial of two EVS, it was found that in an industrial precinct in which there were no registered voters, the system indicated 1,429 votes for the incumbent mayor, who incidentally won the election by 1,425 votes [Mercuri 2001]. In 2002, in the realm of a presidential election, an electronic voting machine attributed to a candidate a final vote count of negative 16,022 votes [Schneier 2004b]. In the same year, in the second round of a presidential election, the final result of the election was decided by five votes, however it was found that the e-voting system had not registered 78 votes [Dill et al. 2003]. One year later, an electronic voting system reported results of 140,000 votes, when only 25.000 residents were eligible to vote [Schneier 2004b]. In 2006, an election was won by only 386 votes out of about 150.000, losing the trail to 18.000 votes [Schneier 2006]. In 2007, several EVS were tested resulting in tabulations whose values differed from those derived from manual tabulation in 56.1% of the votes counted [Open Rights Group 2007]. Any of these incidents has the potential to undermine the trust that people place in e-voting, raising doubts about its value and increasing people’s reluctance to use such systems, in light of the dangers and risks they entail.

The concept of trust requires that there has to be a risk to the parties involved in the trust process and an interdependence between the parties since at least the interests of one of the parties can only be achieved if there is collaboration from other party [Brei and Rossi 2005]. Not being static, trust is situational, evolves based on the ability to predict the behavior of the other and it typically emerges and builds up based on past experiences.

In voting systems, as important as meeting the requirements, systems need to convey that those requirements are effectively satisfied.

In the case of e-voting, there are authors who advocate the printing of electronic votes and the transparency of the system by opening the source code as a way to transmit the necessary confidence to voters [Crane et al. 2004; Dill et al. 2003].

For remote electronic voting systems, the difficulties of ensuring and demonstrating trust seem to become more acute. In a 1999 study, 69% of the voters surveyed believed that secure Internet voting would take many years to become reality or perhaps would never be achieved [Jones 2000]. One decade later, there is still no EVS architecture able to reasonably provide a sufficient degree of trust to the electoral stakeholders. In fact, the simple consideration of the differences in terms of the scaling of voting systems structure shows that an attack in PBVS usually affects a limited number of ballots (those circumscribed to a ballot box), whereas in the case of EVS a simple modification may change the content of thousands of votes [Mercuri 2002].

After pondering on e-voting literature, we advance the following issues as potentially influencing trust in electronic voting systems:

Information made available—the quantity and quality of information and briefings sessions about the e-voting system may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

History of use—the number of times an electronic voting system was used without presenting significant errors may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

Open source code—the ability to inspect the source code of the system may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

Scope of election—different elections will make voters trust differently in the system

Tests—the quantity and quality of the tests made to the system may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

Audits and Certifications—the existence of audits and certifications from the system development process up to the elections may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

Development team—the recognition and reputation of the team that developed the system may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

Ability to meet requirements—the ability of a system to meet requirements, especially those related to the anonymity of the voter’s ballot, may influence the voters’ confidence in the system

This list of issues forms the starting point for the identification and analysis of the factors that may influence the confidence in EVS. It will be important to determine whether the proposed issues are relevant to voters and whether there are other factors that voters consider imperative.

3. Research Design

The purpose of this study is to identify the factors influencing voters’ confidence in EVS. This goal could only be accomplished through the involvement of voters. Since the focus is on trust in EVS, it would be important that the study’s subjects possessed experience of using these systems as this would allow drawing conclusions based on the use of EVS rather than on the intention to use EVS.

To this end, it was necessary to identify individuals who already had used EVS in situations of real elections. The authors knew a Portuguese university that had developed and regularly used a remote electronic voting system. After granting access to this research site, the inquiry was designed based on the existence of that population of voters.

The first version of the aforementioned remote e-voting system was developed ten years ago and the system has been used in several internal elections at the departmental and school levels of the university, with a number of voters ranging from few tens to half a thousand. The typical users of the system are the professors of the institution. The system was one of the first of its kind to obtain the positive opinion of the Portuguese Data Protection National Commission and it is equipped with a set of security mechanisms that aim to instill transparency in the system.

Methodologically, the study consisted in a case study. For the delimitation of the case we defined as subjects of interest all the professors who, belonging to the engineering school of that university, had used at least once the remote e-voting system to exercise their voting rights in the context of a real election.

In carrying out the study we applied two research techniques: collection of documents and semi-structured interviews. The first technique involved the collection of documentation on the system in order to understand its architecture, features, and functionality. The second technique was the main instrument to generate data on the factors that may influence the confidence of voters in EVS.

Previously to conduct the interviews, we developed the interview script, tested the quality of the script by asking two voters to review its wording, and elaborated a preliminary version of the codebook that would support the coding stage.

The script of the interview was structured around the following five themes:

Assessment of the use of the remote electronic voting system

Opinion on EVS before using an electronic voting system and after its use

Key requirements that remote electronic voting systems should satisfy

Use of EVS at national elections or referendums

Main factors influencing the confidence in EVS

The preparation of the preliminary codebook involved the definition of a set of codes based on the literature review and on the questions that made up the interview script.

It was also decided that the first four interviews would serve as pilot, to ensure that the script enabled the generation of data with enough quality to feed analysis.

At the beginning of each interview we would request the respondent if we could audio record the interview. Then, interview records would be transcribed and coded. In order to facilitate mechanical procedures associated with coding and analysis we would use Atlas.ti qualitative data analysis software.

4. Description of Study

The documents on the remote e-voting system were obtained from the system development team, which was composed of technical elements from the IT area and elements from the legal area.

Regarding the interviews, 259 emails were sent to the faculty of seven departments of the school with an invitation to participate in the study. The emails asked professors an interview related to their use of the system. Of the 259 invitations sent, 26 were directed to the department faculty where the system best fit in terms of scientific area, namely the department of information systems and technologies. We attempted to promote a significant number of interviews with professors pertaining to other departments, in order to avoid that findings would be based on a too technical view of the system.

In the invitation email we described the study, emphasized the importance of voters’ collaboration, and assured the anonymity of the participants and that the data collected would only be used in the study. Although we asked for an individual interview in person, we also suggested as an alternative the possibility of interviews being conducted with the use of online communication tools, or as a last resort to the possibility to send the questions by email and receive the answers also by email.

Of the 259 invitations sent, we got 51 acceptances to participate, 24 indications from professors who so far had not used the system (and therefore did not constitute subjects of the study), six responses from professors who were not available to schedule the interview for the period stipulated for the interviews and 14 system messages of email undelivered due to inexistent or full mailboxes.

Most interviews were conducted in person at the professors’ offices during June and July 2011. The distribution of the 51 respondents by scientific area of the department is as follows: 15 (29.4%) from information systems and technologies, 9 (17.6%) from electronics, 9 (17.6%) from civil engineering, 9 (17.6%) from production engineering, 5 (9.8%) from mechanical engineering, and 4 (7.8%) from textile engineering (one of the departments to which we had sent 23 invitations provided no feedback).

At the beginning of each interview we recalled the aim and scope of the study, reinforcing that the answers would be treated anonymously and solely for purposes of the work, and the absence of any linkage between the researchers and the development, maintenance, or promotion of the system. Next, we requested permission to audio record the interview.

Fifty interviews were in person and one was held via Skype. Four respondents did not allow the audio recording of the interview. Interviews amounted to a total of about 10 hours, with an average of 40 minutes per interview, and originated 434 pages of transcripts.

As already mentioned, we started the coding stage with a provisional codebook, since it was not possible to establish a priori all the categories in which the responses of participants would be classified. Therefore, as the analysis of the interviews progressed, we extended the codebook as required, in a process inspired by Grounded Theory. Whenever a new issue arose in the interview, a new code was created and defined in the codebook. Sometimes the addition of the code to the codebook required the review of previous classifications, especially when the introduction of this new code led to an explosion of an existing code into subcodes (the readiness of retrieving previously coded units of text with a certain code provided by Atlas.ti greatly simplified this task). At the end of the coding stage, the codebook contained 166 codes, of which 35 were super codes.

5. Results

The presentation of the main results of the study will follow the five structural themes listed in the research design section.

Overall, the respondents assessed positively the remote electronic voting system they had used. Regarding the usability of the system, 82.7% of the interviewees were satisfied. Those that criticized the system pointed to difficulties in finding the email message they had received with details regarding the election, to prefer that this message had been sent from an institutional email address, and to issues with the web browser interface or the need to install a browser add-on for the system to work properly.

With regard to the information provided about the voting process, 70.6% of the interviewees did not retain much more than basic information about the system (username, password, and URI). Still, 84.4% considered to be perfectly clear with the information received.

On the composition of the system development team, there was unanimity among respondents that the team should include elements from the legal area, in addition to elements from the IT area. In what concerns the need to integrate into the team elements from other areas, 61.1% of respondents did not consider that additional areas of knowledge were in need in the development team, 16.7% claimed that it would make sense to integrate elements from psychology, and 11.1% suggested the inclusion of elements from sociology and ethics.

Given that the Portuguese Data Protection National Commission had issued an opinion on the system, we tried to find out if voters knew it and how they regarded it. Only 9.8% knew the opinion and its contents, 78.4% were unaware of its existence, and 11.8% knew of its existence, but were unaware of its contents. After informing the voters about that opinion and its positive result, 74.5% of the participants considered it very positive and important for promoting confidence in the system.

In order to increase the transparency of the voting process, the system allows the provision to the voter of a numeric code for confirmation of the vote cast in the system. Questioned about this system’s feature, 48.6% of the interviewees stated to be unaware of it. Among those who knew it, 21.6% resorted to this mechanism and verified that the system correctly indicated the voting option they had expressed, and 16.2% did not experiment the functionality. Concerning the importance of this mechanism, 65.7% of the interviewees considered it an important measure, 14.3% classified it as a minor feature. However, of the remaining 20% respondents who disagreed with the usefulness of the measure, 8.6% peremptorily argued that this feature might indicate an insecure system, since it allowed to associate codes, to voters and to votes.

The second theme of the interview script concerned the participants’ opinions on EVS before using an e-voting system and after its use. Regarding the opinion prior to the use of such a system, 44.6% stated they had never thought about it before the use, 28.6% indicated having a favorable opinion, and 26.8% reported some suspicion and apprehension. After using the system, 93.0% of the respondents considered that they felt so confident using EVS as if they had used the traditional voting system. This view is reinforced by the fact that only 8.3% of the participants would select the traditional voting system if they could choose between the two systems. Curiously, when questioned whether the vote may be more compromised when EVS are used instead of the traditional system (in the sense of a third party knowing the voting option of a voter), 14.6% of the interviewees considered that the vote is no more compromised in the case of e-voting, 43.8% thought it may be more compromised, and 33.3% stated that although personally they did not think so, they conceived that this could be the understanding of other people.

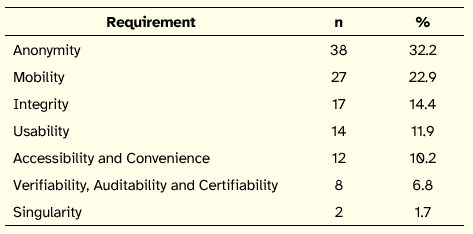

Regarding the main requirements that an e-voting system should satisfy (the third theme of the interview), the respondents provided 118 indications categorized as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Main Requirements of e-Voting Systems

Still concerning the requirements of EVS, we asked if respondents had verified or tried to verify if the remote electronic voting system that they had used met the requirements they pointed to. Only 11.1% stated they had examined, albeit very superficially, some of the requirements. The remaining 88.9% asserted they had not carried out any verification.

The fourth theme relates to the possibility of using EVS at the national level. With regard to the use of REVS, half of the participants believed that their use would not be desirable, mainly because there is a set of requirements that can not be met due to the existence of various risks, such as those related to the technical infrastructure, coercion, large scale, and voters’ authentication. On the other hand, 35.4% of respondents considered that using EVS would be possible and 4.2% considered it possible, but as an alternative method operating in parallel to the traditional voting system. In the case of PEVS, 23.9% replied negatively to the application of these systems since they would add little value to the voting process, 41.3% provided a positive response, 4.3% considered it possible, but as an alternative method to the traditional voting system, and 30.4% had no opinion.

We also asked participants if they would be willing to give up of some requirements, such as anonymity, integrity of the vote, or uncoercibility, in order to have mobility, increased speed, and reduced costs with the voting process. Surprisingly, 75.6% of respondents answered affirmatively.

The fifth and final theme was related to the factors that would influence voters’ confidence in EVS.

With regard to the availability of the system source code, 40.4% of respondents believed that the code should be closed, except for the auditors, 25.0% advocated open source systems, and 25.0% stated to be indifferent.

On the nature of EVS certifications, and given that the Data Protection National Commission’s opinion reflected a strictly legal assessment without relying on a technical (IT) evaluation of the system, 77.6% participants stated that the legal evaluation should be complemented by a technical evaluation, while 22.4% considered that the technical evaluation was not needed or was not essential.

Another question aimed to establish if the electoral commission which promotes and monitors the electoral process could influence the confidence in the system, i.e., if the reputation and idoneity of its members could instill in voters greater confidence. Faced with this question the opinions were divided: 56.3% of respondents believed that this could be the case, while 43.8% considered that those were independent factors.

Interviewees were also asked whether they were aware of negative past experiences with other EVS and whether these negative experiences could shake the confidence of voters, particularly during the debate on the possible adoption of EVS at national level. Approximately 70% of respondents were not aware of those experiences. Faced with factual accounts of some of the experiments, 70.2% reported that such information might adversely affect public opinion and demolish any attempt to implement EVS at national level. On the other hand, 29.8% of the respondents believed that each system should be treated as a separate system, and although these experiences might be used as political weapons in a debate on the adoption of EVS, people would be able to distinguish between the situations.

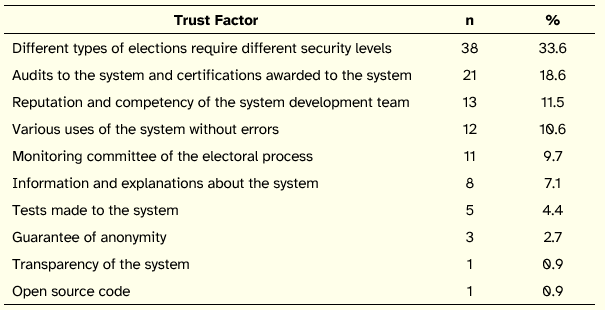

Regarding the main factors that influence the confidence of respondents in EVS, the analysis of the interviews led to the aggregated results in Table 3.

Table 3: Main Factors Influencing Trust in EVS

6. Discussion

The positive assessment of the electronic voting system is supported in a large majority of respondents that claimed to trust the system. To this general opinion we may oppose the fact that a significant number of respondents did not check if the system met the requirements, was unaware of certain features of the system and that the system had been certified by the Data Protection National Commission. The explanation for this apparent inconsistency may rest on participants placing their confidence in the system development team and in the electoral commission, and on the acknowledgment that they did not have major concerns on using the system given the limited scope of the elections.

Before using the system, many participants had not formed an opinion on evoting since they had never reflected on this subject, others indicated they had some apprehension about this particular technology and the risks it entails, still others were more receptive to the use of e-voting, perhaps because they had greater propensity to the use of IT. After using the system, the majority of participants were more confident in this type of systems, with less apprehension, but revealed that after going through the process it remained the feeling that the freedom to vote may be more compromised in EVS than in the traditional system. Therefore, a perception that when using EVS something can go wrong and that the vote that was expressed may be revealed and so the voter may suffer the consequences does persist.

The possibility of using e-voting in broader elections also raises divisions. On the one hand, there is a more conservative line of participants that advocated a gradual transition, from the traditional voting system to PEVS and then to REVS. On the other hand, a large proportion of respondents considered that PEVS are no longer attractive. Finally, there is a large group that thinks it is very difficult to use REVS in national elections.

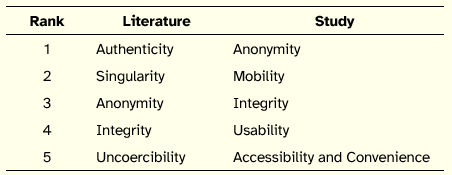

By comparing the five core requirements of EVS that were extracted from the literature with the five requirements most cited by participants we find significant differences, as illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4: Comparison of Core Requirements of EVS

Although a definitive conclusion might not be possible (the ordering of requirements extracted from the literature resulted from the authors’ interpretation of the relative importance researchers attribute to the requirements and the participants’ ordering is limited to the case analyzed), we find that only two requirements are common. Albeit respondents may have taken for granted certain requirements, it stands out the importance attributed to anonymity and mobility, as well as the emphasis placed on REVS usability, a requirement less stressed in the literature.

The issues initially proposed as potentially influencing voters’ confidence in EVS were expressed by participants as relevant to the process of building trust in EVS.

The most cited factor by voters during the interviews was the scope of the elections: elections with different scope and relevance demand different levels of trust in the system, so that the degree of confidence in the system will vary with the election in question.

In the second place come system audits and certifications. For the other factors which influence confidence in EVS opinions are divided. One example concerns if the system source code should be open or closed. A large group of participants argued that the code should be closed, except for audit purposes. Another significant group of respondents (closest to the IT area) only conceived confidence in this type of systems if the source code was open.

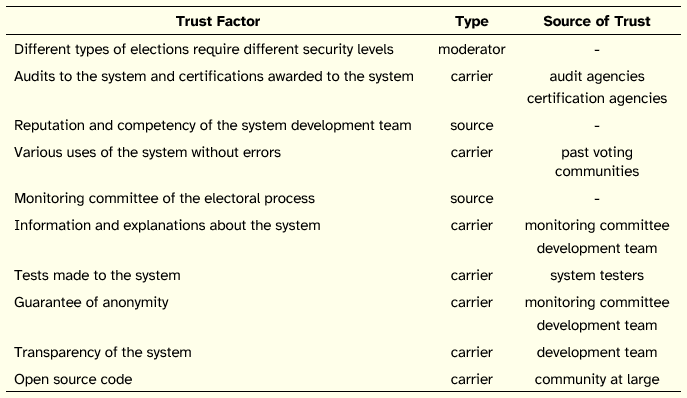

The factors that were identified as influencing trust in EVS are inherently different. The first factor—the scope of the election—acts as a moderator of trust: the larger the electorate and the more important elections are the greater the demands of voters to trust the system. Other factors, such as the system development team and the monitoring committee, represent sources of trust, i.e., entities that directly instill voters with trust in the system. The remaining factors may ne viewed as carriers of trust, i.e., technologies and procedures that convey confidence in the system. These carriers serve as propagators or transmitters of trust from the sources of trust. Hence, in the case of audits and certifications, the sources of trust are the agencies that assess and certify the electronic voting systems, the audit reports and the certificates are the vehicles (carriers) of trust of those sources.

Applying this interpretation regarding the nature of trust factors leads to the characterization shown in Table 5, where each factor was classified in terms of type (moderator, source of trust, or carrier of trust). For the carrier factors, we suggest the corresponding sources of trust.

Underlying these factors there is a set of beliefs held by people. For instance, regarding the scope of the election there is the belief that elections with higher number of voters have higher levels of complexity and increased risks. Given this escalation, voters require stronger evidence that the system remains worthy of trust. The case of open source code is also illustrative: it can be argued that underlying this factor is the belief that if the system source code is made publicly available, the community as a whole (actually a very limited and specialized subset of that community) may scrutinize it, or if an individual of that community modifies the code, the community will detect it and react against the modification. An alternative belief is that if the code is open is can be more easily exploited by malevolent individuals who will then be able to attack the system. According to this belief, source code should be carefully protected, namely by keeping it closed.

Table 5: Characterization of EVS Trust Factors

In the end, we may be able to reduce the phenomenon of trust in EVS to the credibility that voters attach to the sources of trust and to the reliability they recognize carriers of trust possess. The sources of trust that a voter chooses and the carriers of trust that a voter favors both depend on the beliefs of the voter. Isolating these beliefs, identifying the sources of trust, and assessing the carriers of trust may be the way to understand the degree of confidence voters place in an e-voting system and to provide the means to build and deploy trustworthy EVS.

7. Conclusion

In this study we identified the factors that influence voters’ confidence in electronic voting systems by undertaking a case study on the use of a remote electronic voting system in which 51 voters were interviewed.

The main contribution of this work is the list of factors that voters consider influence their confidence in EVS, in order of relevance and characterized according to the role they play in the process of instilling trust in voters. Another contribution of this study is the set of requirements that respondents claimed to be essential to EVS to satisfy, and its comparison with the set of requirements extracted from the literature.

The findings of the case study embody a set of recommendations to be taken into account in the implementation of voting processes using IT systems.

We also argue that by considering the nature of each of the factors—moderator of the degree of trust, source of trust, or carrier of trust—we are better equipped to understand the degree of confidence that voters place in this type of systems, as well as the processes underlying the formation of voters’ attitudes in what concerns the adoption and use of EVS.

The work enriches the literature by focusing on the factors that electors favor as definers of their confidence in EVS. This complements several propositions of EVS architectures found in the literature that seek to address specific security requirements from a technical point of view. Hence, the findings provide context mfor the use of EVS by voters. By knowing what fosters trust on EVS from the perspective of voters, we will be in a better position to design trustworthy voting processes and systems, as well as to devise improved procedures to verify and audit their technical properties.

The study has several limitations. Although it is not easy to find voters who have already used remote electronic voting systems, a larger number of interviews would allow a deeper understanding of the processes and conditions that lead to the establishment of a relationship of trust between voters and EVS.

Another limitation relates to the characteristics of the case study, since the elections analyzed refer to a small universe of voters, have a restrict scope and were promoted within a controlled and culturally homogeneous environment. In addition, the participants in this study are extremely qualified individuals with a high cultural level, so this group of voters is not representative of the electorate.

This paper reports an exploratory study on EVS trust factors which leaves open many opportunities for future work. We restricted the study’s subjects to voters and it would be worthy to obtain a view of other stakeholders in the process of EVS adoption, such as developers and auditors, and to find out whether the factors that these groups recognize as influencing trust in e-voting differ from those found in this study.

Another work would be to build a variance model based on the trust factors identified and test the causal relationships with a research design that involved a representative sample of the electorate at the national level.

A more qualitative research would be to build a model to explain the process of formation, maintenance, and deterioration of stakeholders’ trust in EVS.

Besides these proposals for future work, there are specific issues that arose during the study and that require a better explanation, such as the reasons that led some voters to consider that the vote might be more compromised in EVS than in the traditional voting system and the extent to which voters are willing to sacrifice certain requirements of the voting process in favor of other requirements.

These are research opportunities worth pursuing so that we can better understand trust in e-voting systems and to improve the chances of EVS being successful.

References

ACE (2001). Opportunities, risks and challenges of e-voting. ACE Project, The Electoral Knowledge Network. http://aceproject.org/

Antoniou, A., C. Korakas, C. Manolopoulos, A. Panagiotaki, D. Sofotassios, P. Spirakis and Y. C. Stamatiou (2007). A Trust-Centered Approach for Building E-Voting Systems. In Wimmer, M.A., J. Scholl and A. Grönlund (Eds.), EGOV LNCS 4656, 36–377. Heidelberg: Springer.

Antunes, P. (Ed.) (2008). Voto Electrónico—Discussão técnica dos seus problemas e oportunidades. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

Brei, V .A. and C. A. V. Rossi (2005). Confiança, valor percebido e lealdade em trocas relacionais de serviço: um estudo com usuários de Internet Banking no Brasil. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 9, 145–168.

CE (2004). Legal, Operational and Technical Standards for e-Voting. Recommendation Rec. (2004) of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe Publishing.

Crane, R. E., A. M. Keller, A. Dechert, E. Cherlin and D. Mertz (2004). A Deeper Look: Rebutting Shamos on e-Voting. http://www.acm.org/crossroads/xrds2-

4/voting.htmlCranor, L. F. and R. K. Cytron (1997). Sensus: A Security-Conscious Electronic Polling System for the Internet. Proceedings of the Hawai International Conference on System Sciences. Wailea.

Dill, D. L., B. Schneier and B. Simons (2003). Voting and Technology: Who Gets to Count Your Vote? Communications of the ACM 46(8), 29–31.

Frith, D. (2007). E-voting security: hope or hype? Network Security 11, 14–16.

Granneman, S. (2003). Electronic Voting Debacle. Security, http://www.securityfocus.com/columnists/198

Gritzalis, D. A. (2002). Principles and requirements for a secure e-voting system. Computers & Security 21(6), 539–556.

Grove, J. (2004). ACM Statement on Voting Systems. Communications of the ACM 7(10), 69–70.

Hall, J. L. (2008). Policy Mechanisms for Increasing Transparency in Electronic Voting. PhD Dissertation. University of California at Berkeley, USA.

Jones, B. (2000). A Report on the Feasibility of Internet Voting. California Internet Voting Task Force, Sacramento, USA.

Jones, D. W. (2001). Voting and Elections. The University of Iowa, USA. http://www.divms.uiowa.edu/~jones/voting/

Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis and F. D. Schoorman (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review 20(3), 709–734.

McDaniel, P., A. Aviv, D. Balzarotti, G. Banks, M. Blaze and K. Butler (2007). EVEREST—Evaluation and Validation of Election-Related Equipment, Standards and Testing. http://www.patrickmcdaniel.org/pubs/everest.pdf

Mercuri, R. (2000). Questions for Voting System Vendors. http://www.notablesoftware.com/checklists.html

Mercuri, R. (2001). Electronic Vote Tabulation: Checks & Balances. PhD Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, USA.

Mercuri, R. (2002). A better ballot box? IEEE Spectrum 39(10), 46–50.

Monteiro, A., N. Soares, R. M. Oliveira and P. Antunes (2001). Sistemas Electrónicos de Votação. Technical Report, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal.

Neumann, P. G. (1993). Security Criteria for Electronic Voting. Proceedings of the 16th National Computer Security Conference. Baltimore.

Neumann, P. G. (2004). Special Issue: The problems and potentials of voting systems. Communications of the ACM 47(10), 28–30.

Open Rights Group (2007). May 2007 Election Report—Findings of the Open Rights Group Election Observation Mission in Scotland an England. http://www.openrightsgroup.org/wpcontent/uploads/org_election_report.pdf

Randell, B. and P. Y. A. Ryan (2006). Voting Technologies and Trust. IEEE Security and Privacy 4(5), 50–56.

Schlienger, T. and S. Teufel (2002). Information Security Culture: The socio-cultural dimension in information security management. Proceedings of the IFIP TC11 International Conference on Information Security, 191–202.

Schneier, B. (2004a). Getting Out the Vote: Why is it so hard to run an honest election? San Francisco Chronicle, October 31.

Schneier, B. (2004b). What’s wrong with electronic voting machines? OpenDemocracy, http://www.opendemocracy.net/media-voting/article_2213.jsp

Schneier, B. (2006). Did Your Vote Get Counted?, http://www.schneier.com/essay-133.html

Shamos, I. (1993). Electronic Voting—Evaluating the Threat. Proceedings of the Third Conference on Computers, Freedom and Privacy, 3.18–3.25. Burlingame.

Strauss, C., D. Mertz and K. Dopp (2005). Electronic Voting System Best Practices. http://electionmathematics.org/em-votingsystems/Best_Practices_US.pdf