Original source publication: Meira, B. and F. de Sá-Soares (2013). Trust Factors in the Adoption of National Electronic Health Records. Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services—Healthcom 2013. Lisbon (Portugal).

Trust Factors in the Adoption of National Electronic Health Records

Centro Algoritmi, Universidade do Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

In the area of health, the Electronic Health Record (EHR) is increasingly seen as essential not only to ensure interoperability between systems, but also to assume the patient as the central entity of the health information. The success of the EHR depends on several factors of diverse nature, such as technical, ethical, legal security and privacy. In the case of the adoption of new technology, an additional and particularly important class of factors is the one related to trust. The different entities that handle health information (doctors, patients, managers, etc.) have different needs and goals for the EHR and, therefore, evaluate their individual trust based on different factors. Assuming that the trust placed in the EHR by its main stakeholders is a relevant factor in its success, a set of factors influencing trust were identified and classified through a field study. The target of analysis was the Portuguese EHR initiative.

Keywords: EHR; Electronic Health Record; Trust; Trust in Technology; e-Health

1. Introduction

The adoption of a national Electronic Health Record (EHR) has significant impacts on the way citizens interact with the health system and the health professionals. To judge the success of an EHR, the initial degree of acceptance of the system by its intended users should be considered as well as the subsequent use of the system. Actually, the formal adoption of this type of systems is, in most cases, irreversible. What this means is that if the system does not adequately fit users ’ needs, it is rather unlikely that the health professionals and patients revert to whatever system they had previously. The most likely scenario would be that both health professionals and patients would make minimal use of the system, causing the system to fall short in terms of its promised benefits.

Besides key technical factors, other issues may influence the successful adoption of EHR by its stakeholders, particularly health professionals and patients. Considering the complexity and sensitiveness of the information manipulated by such a system, we postulate that trust factors also play an important role. Indeed, the literature show s there is a strong relationship between trust in a technological system and its use [Gefen et al. 2003; Kassim et al. 2010].

This study aims to identify and classify the main trust factors that have an influence in the adoption of the EHR by health professionals and patients. By knowing these factors, designers will be better prepared to project EHR systems aligned with users’ requirements and expectations, and implementers will increase their chances of correctly managing the change process associated with the introduction of this kind of systems.

The remaining sections of this paper are organized as follows: in Section 2 (Concepts) we review the core concepts for this work; in Section 3 (Methodology) the adopted methodology for the study is outlined ; in Section 4 (Study Description) we provide details about the conducted field study; in Section 5 (Results) we present our main findings; followed by their discussion in Section 6 (Discussion); and in Section 7 (Conclusion) we draw conclusions and suggest future work.

2. Concepts

To properly analyze the issue of trust in the EHR, it is important to concisely define both concepts.

Trust in the EHR implies trust at very different levels. The doctor patient relationship is a delicate one, and the implementation of an EHR adds new complexity to that relationship. Both clinician and patient (albeit for different reasons) need to trust in the EHR. If they do, both patient and clinician need to trust in who designed the EHR they are using, in who is responsible for maintaining the information and in the systems managing that information, among others. To trust in the EHR is to delegate discretionary powers (whether consciously or not) to additional entities.

Trust factors may be classified according to three dimensions: Dispositional, Institutional and Interpersonal [McKnight 2001].

The dispositional dimension relates to an individual’s disposition to trust others, and intends to capture ones assertions about its peers. In this dimension the entity that is the target of the trust is irrelevant.

The institutional (or structural) dimension captures the environment in which trust relationships occur. Similarly to the prior dimension, the institutional dimension relates to external factors that may influence, govern or limit any given trust relationship. In the particular case of the doctor patient relationship, the individual trust placed by a particular patient in a particular clinician is influenced by the ethical code to which the clinician adheres to.

The interpersonal dimension is the personal side of the trust relationship, and therefore relates to the individual perceptions and intentions of the trustor in regard to the trustee. In contrast to the previous dimensions, the interpersonal dimension is based on judgments and perceptions about specific entities. In a broad sense, the environment in which trust occurs and one’s perception about others influence one’s perceptions and intentions in relation to a particular subject. This dimension may be subdivided into perceptual, intentional and behavioral categories. Of these, the perceptual category is particularly relevant for this study since it captures the trusting beliefs of trustors regarding trustees. At the operational level it includes four aspects, namely competence (to be able to do for one what one needs done), benevolence (to act in one’s interest instead of opportunistically), integrity to make good faith agreements, tell the truth and fulfil l promises) and predictability (to forecast trustee’s actions based on the consistency of previous actions).

The combination of the three dimensions of trust influence ones behavior towards others. Therefore, the behavioral perspective of trust is the physical manifestation of trust (or the lack of it). As an ex ample, by sharing information with someone we are behaving as if we trust that someone.

Most of these concepts are usually expressed in terms of people trusting other people. However, this is not necessarily always so. Trust between people is often mediate d by institutions (Institutional dimension). Trustor and trustee often trust that a given institution can settle eventual disagreements. In the case of trust in technology, the same principles apply, with the exception that, contrary to humans, technology lacks free will and moral or ethical principles [McKnight 2005]. Apart from the lack of free will or moral, which impacts the interpersonal dimension of trust, the remaining aspects of trust are equally applicable to the analysis of trust in technological artifacts.

3. Methodology

The methods used in this study will be outlined in terms of data collection and data analysis. Regarding the collection of data, the chosen approach was a field study, in which a series of interviews were conducted. The technique used in these interviews can be described as Active Interviews [Holstein and Gubrium 1995]. The selected technique allows the subject of the interview a certain degree of freedom, and a higher interaction between the interviewee and the interviewer. Given the objective at hand, understanding what raises or lowers the user s trust in the EHR, a too strict approach (like a questionnaire) would raise some concerns. Namely, it would be very difficult to ascertain if the interviewee understood what was being asked of him and, also, it would not give the interviewee a chance of presenting problems or concerns not previously foreseen by the authors.

For the process of data analysis, the chosen approach was Content Analysis based on Grounded Theory, in which the propositions or theories are derived from a systematic data analysis process [Myers 2012]. The generic technique used for the data analysis process is known as coding , the process in which the interviewee s answers are grouped together by associating them with common ideas or concepts [Rubin and Rubin 1997]. This technique involved the definition of a codebook: a document containing the codes, their meaning and instructions for applying them. The basis for defining the codebook was the trust framework proposed by [McKnight 2001] and briefly reviewed in the previous section.

4. Study Description

The field study took place between the months of June and August of 2012 in Portugal. Briefly, and to put this study into context, in 2009 the Portuguese Government launched an initiative to implement a national EHR, named RSE (Registo de Saúde Eletrónico, in Portuguese). In 2011 the initiative was reconfigured to the implementation of a web based electronic service to access and manipulate EHR.

The number of subjects interviewed was 63, of which 17 (27%) are health professionals and 46 (73%) are patients. From the 17 health professionals, six are nurses, five are general practitioners, five are specialized doctors and one is a psychologist.

The average length of the interviews was 11 minutes for the patients (with a minimum, maximum and standard deviation of 5.3, 24.4 and 4.2, respectively) and 27 minutes for the health professionals (minimum, maximum and standard deviation of 14.4, 47.1 and 7.2, respectively). All interviews were conducted in places and times of the day chosen by the interviewees. All interviews were audio recorded.

Although we do not claim (neither intended) to have formed a statistically relevant sample (the selected methods alone would make this task significantly difficult), a n effort was made to assure there was a minimal correspondence between the patients’ profiles and national indicators regarding age and educational level.

Each of the two groups interviewed (patients and health professionals) had different interview scripts. The main difference between the two scripts was the focus of the topics. The patient script was more focused in determining the level of comfort with information technology, the level of awareness to patient rights regarding health information, the interaction between the patient and the health system and the patients’ opinions and thoughts on what they valued as important in the EHR. The health professional script was more focused in determining the level of awareness to the national e-Health initiatives, the normal workflow used by the professionals, the different kinds of records they worked with (electronic, paper or both), the acceptable uses given to the information and, as in the case of the patient script, their thoughts and opinions about the EHR. Both scripts approached some common topics such as with whom should this information be shared and what level of control should patients have. All interviewee s were welcomed to discuss topics not covered by the script (but connected to the interview theme) and the interviewer guaranteed anonymity for all participants.

The coding process was supported by appropriate software, and all the interviews were directly coded in audio format. On this subject, it is important to make a note regarding the dimensions used. Despite the warning made by [McKnight 2005], the integrity aspect of the interpersonal dimension was considered when the subject was referring to a computer system. That aspect was used as a measure of the user s expectations. This may be easily illustrated with regards to information access. There is a significant difference between the system s capacity (or competence in the terminology used by [McKnight 2001]) to handle multiple accesses to patient data and the righteous access to that same data. In the case of this study, system integrity serves as a mediator between the expected behavior of the system, and the eventual reality of the same system. The decision to include the integrity aspect was made during the analysis of the interviews, when it was noted that the focal point of the subjects was not the system s capacity, but their own perceptions of what the system should or should not permit. In line with [McKnight 2005], we did not consider that the benevolence aspect would make sense when analyzing trust in technology.

5. Results

A. Demographic Data

1) Patients

Regarding access to health services, the majority of interviewed patients (78%) use the national health service. Some patients resort both to public and private health services.

In terms of frequency of access to health services, the average is 3.6 times per year. The lower registered frequency is once every three years and the maximum registered frequency is between 24 to 36 times per year (cases of hemodialysis or similar situations).

Regarding appointment scheduling, the preferred method of scheduling is personal attendance (50%), followed closely by scheduling via phone call (44%). The less used channels of appointment scheduling are in loco (scheduling from one appointment to another 24%) and Internet scheduling (11%). Curiously, regular access to a computer, one of the indicators authors expected to be low, is actually quite high (93%), especially considering the age average of the interviewees (47 years). Even more curious is the fact that 63% of the patients claim they fell relatively confident in using a computer. The low use of the Internet for appointment scheduling may be explained by the general lack of knowledge of that possibility (only 24% of the subjects knew of that possibility) and for other factors like bad experiences in using the e-health platform for doing so, or by the fact that the patient does not have a State appointed general practitioner.

Regarding the knowledge of the legislation applicable to personal health data, only 7% of the interviewed patients are aware of it.

From all the 46 patients, none of them considered the RSE as a non-important e-Health initiate and all of them would, if they were given that choice, allow that their health information to be part of a national EHR.

2) Health Professionals

From the 17 interviewed professionals, 11 work in the public sector, one in the private sector and five in both sectors. From the 17 professionals only one (the psychologist) had not worked with electronic health records and did not have a daily access to his patients’ health records. From the remaining 16, all of them have a daily access to electronic health records, and 13 of those also access paper based health records. The average years of experience of the health professionals interviewed was 12 years, and the age average was 37 years.

The less-known e-Health initiative is the RSE, followed by the eAgenda initiative (the possibility of patients scheduling appointments with the State appointed general practitioner).

The applicable legislation to health data is also considerably unknown, 15 of the 17 professionals did not know the actual legislation.

Like the patients, all health professionals considered e-Health initiatives very important and all of them would make use of the RSE if it was implemented, some of them noting however that the definition and select ion of the appropriate technology and tools is not their concern, only the correct usage of those tools.

B. Trust Factors

1) Patients

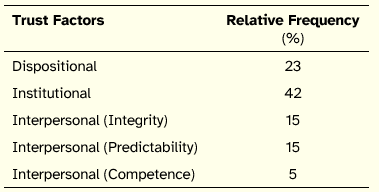

Regarding patients, a total of 152 trust factors and 25 distrust factors were found. Distrust factors are conceptually equal to trust factors (the only difference is the manner in which they are presented), and therefore were analyzed in the same way trust factors were. From these factors, 142 and 7 factors of trust and distrust respectively, are related with the use of information systems. Additionally, a total of 138 opinions about information sharing were registered and 56 opinions about patient access and control of their own health records. The relative frequency of the identified trust factors can be seen in Table 1 in the following tables all figures were rounded to the units).

Table 1. Relative Frequency of Trust Factors (Patients)

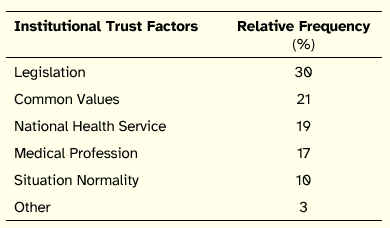

The institutional factors were subdivided in the categories included in Table 2.

Table 2. Relative Frequency of Institutional Factors (Patients)

These values indicate that the most import factor for patients is the compliance with legislation, with their common values (as a society) and with the national health service. It is possible to observe that these indicators have something in common with one another. The existence of a national health service is something that most Portuguese view as an essential common value, and the existence of a national health service is a right advocated in the Portuguese Constitution. Besides these three factors, the remaining ones are divided between trust in the medical profession, and the acceptance of the current trend of modernizing existing structures through information technology (situation normality).

For the patients, the most significant inter personal factors are those related to integrity and to predictability. In the first group, system integrity represents 43%, information integrity 30% and system access integrity 26%. Regarding predictability, the most relevant factor is access to information (59%).

Regarding information sharing, 75% of patients’ opinions are towards full sharing of health information between professionals. However, this does n o t mean that the patient agrees to give unconditional access to the professionals. It means that if the professional requires that access, the access should be to the totality of the record. The remaining 25% maintain that access to some of the information should be restricted. Additionally, 76% of opinions indicate that information sharing with the private sector should be restricted or non-existent (52% incidence on restricted).

On the topic of access and control over one’s EHR, 70% of opinions indicate that patients would like some form of control over their own EHR. The remaining 30% do not wish to have any kind of control over their own EHR.

2) Health Professionals

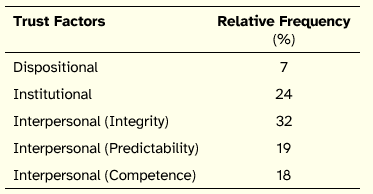

From the health professionals’ interviews, a total of 65 trust and 11 distrust factors were gathered. From these factors, only two distrust factors are not related to the use of EHR. A total of 41 and 27 opinions about information sharing and access or control by the patient of his own EHR were isolated, respectively. The relative frequency of trust factors is displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Relative Frequency of Turst Factors (Professionals)

In the case of the health professionals, there is a significant shift towards the characteristics of the information system, with the interpersonal factors reaching 69%. Among these, integrity related factors are the most relevant, distributed into the following three issues: information integrity (71%), system integrity (17%), and system access integrity (12%).

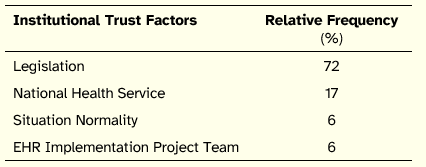

Still, the institutional factors are very significant. This group of factors can be further subdivided in the categories depicted in Table 4.

Table 4. Relative Frequency of Institutional Factors (Professionals)

Compliance with legislation is a significantly relevant factor. In the case of the health professionals, the National Health Service factor also relates with the compliance of the RSE with the principles of public health. It is important to note that, in both cases (patients and health professionals), a relevant issue included in this indicator is the fact that the RSE is a public initiative.

Regarding information sharing, 62% of the health professionals’ opinions indicate that information sharing should have some restrictions, namely that a professional should not have access to the totality of the record. The topic of public private sharing between health professionals is a sensible one, with 42 % indicating that there should n o t be any significant difference between both sectors, and 42 % indicating that there should be restrictions to private public sharing. 17% of opinions also indicate that there should n o t be any sharing of any kind with the private sector (i.e. direct sharing of the EHR).

Finally, on the topic of patient access to and control of their own health record, 93% of collected opinions show that professionals consider patients should have access and/or control over their own EHR. Most of them note however, that caution must be taken to prevent situations where the patient, while exercising this right, may inadvertently contribute negatively to his own health status.

6. Discussion

The results of the study suggest that the two groups interviewed differ in terms of the trust factors they most value. For patients, the most relevant factors are those of institutional nature. For the health professionals, the interpersonal dimension collects the issues most frequently reported. These differences may be explained by considering the distinct concerns of the two groups of EHR stakeholders. Health professionals put greater emphasis on the EHR systems’ features, highlighting the EHR as a pivotal instrument for their job. With respect to patients, they focus the provision of health care, valuing the alignment of the EHR with the national health service by showing compliance with legislation and congruence with common values.

The integrity related factors also hold a strong position, with a bigger emphasis in the health professionals group. However, these factors are also tightly related to what both groups consider as being just, fair and adequate. Actually, it may be impossible to separate these factors from the Portuguese identity and common values. In any case, that same relationship should be valid across different health systems and different national identities, only the core values in question could be different. This study shows that, in the particular case of Portugal, the RSE should not be contrary to what the system is trying to enhance and improve. In short, the RSE should not condemn the required conditions for its own thriving.

The methodology used in this work also helps on the effective prioritization of requirements for the EHR, enabling an efficient match between users’ expectation s and implementation priorities. In order to prioritize requirements for the EHR, the findings can be matched with standards such as [ISO/TC215 2004].

7. Conclusion

Assuming trust is a relevant factor for technological adoption and system use, this paper presented a study that aimed to find out what the users value most concerning trust in EHR. The implementation of a national EHR is a complex and delicate process, with a low margin for error. For that reason alone, understanding what makes patients and health professionals trust an EHR is important. The value of an EHR is directly linked with its use. If the EHR does not comply with its main users expectations, it will most likely be misused or under used.

The trust factors presented in this work do not represent the totality of concerns about e Health initiatives. Nevertheless, given the relationship between use of a system and trust in that system, they form a significant group of aspects to consider that may contribute strongly to the adoption and use of e-Health systems.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it is important to note that its findings are partially limited to the Portuguese culture. The Portuguese people are, in general, strong advocates of a national health system, which is not necessarily true in other countries. Nevertheless, only the core social values should differ, the methodology should remain valid. Addition ally, as it was noted before (cf. section 4 Study Description), we do not claim to have used probability based sampling methods to form our pool of participants.

Three avenues for further research are suggested. The first involves extending the study to collect the views from health system managers. This could prompt a discussion between an eventual utilitarian view of the EHR and the benefits and risks of using the EHR as perceived by health professional s and patients. The second suggestion for future work is related to the replication of this study in a post implementation scenario of the RSE. This would allow a comparison between ex ante trust factors and ex post trust factors, enabling to contrast the intended use of the system with the actual use of the system. The third suggestion regards the sharing of health information between the public and private sector. Besides identifying the information that should or could be transfer red between the two sectors, it would be interesting to reflect on the technical and organizational security challenges and solutions involved in that sharing process.

References

Gefen, D., E. Karahanna and D. W. Straub (2003). Trust and TAM in Online Shopping: An Integrated Model. MIS Quarterly 27(1), 51–90.

Holstein, J. A. and J. F. Gubrium (1995). The Active Interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

ISO/TC215 (2004). ISO/TS 18308 Health informatics—Requirements

for an electronic health record architecture. International

Organization for Standardization.ISO/TC215 (2005). ISO/TR 20514 Health informatics—Electronic Health Record Definition, Scope and Context. International Organization for Standardization.

Kassim, E., N. Zamzuri, S. F. A. Kader and H. Hanitahaiza (2010). Investigating information technology adoption success: the influence of fit and trust. IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation and Technology (ICMIT) 2010, 35–39.

Lewis, J. D. and A. Weigert (1985). Trust as a Social Reality. Social Forces 63(4), 967–985.

Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis and F. D. Schoorman (1995). An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Academy of Management Review 20(3), 709–734.

McKnight, D. H. (2005). Trust in information technology. Blackwell Encyclopedia of Management 7, 329–331.

McKnight, D. H. and N. L. Chervany (2001). Trust and distrust definitions: One bite at a time. Trust in Cyber-societies, 27–54.

Myers, M. D. (2012). Qualitative Research in Information Systems.

http://www.qual.auckland.ac.nz/#Qualitative%20Research%20MethodsRubin, H. J. and I. Rubin (1997). Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.