Original source publication: Lopes, I. M. and F. de Sá-Soares (2014). Institutionalization of Information Systems Security Policies Adoption: Factors and Guidelines. IADIS International Journal on Computer Science and Information Systems 9(2), 82–95.

The final publication is available here.

Institutionalization of Information Systems Security Policies Adoption: Factors and Guidelines

a Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Portugal

b Centro ALGORITMI, Departamento de Sistemas de Informação, Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Abstract

Information systems security policies are pointed out in literature as one of the main controls to be applied by organizations for protecting their information systems. Despite this, it has been observed that, in several sectors of activity, the number of organizations having adopted that control is low. This study aimed to identify the factors which condition the adoption of information systems security policies by organizations. Methodologically, the study involved interviewing the officials in charge of information systems in 44 Town Councils in Portugal. The factors facilitating and inhibiting the adoption of information systems security policies are presented and discussed. Based on these factors, a set of recommendations to enhance the adoption of information systems security policies is proposed. The study used Institutional Theory as a theoretical framework.

Keywords: Information Systems Security Policies Adoption; Information Systems Security; Institutionalization; Institutional Theory

1. Introduction

Although the essentiality of ISS policies is claimed by most authors, the truth is that there is, simultaneously, the perception that a significant number of organizations have not yet adopted this ISS control. In order to assess the validity of this perception, Lopes and de Sá-Soares [2010] have collected empirical data on organizations’ effective adoption of ISS policies. In this regard, they carried out a census in Local Public Administration in Portugal, whose results show that among the 308 existing Municipalities, only 12% (38) indicated the possession of ISS policies. The results of that census provided support for the perception that there is still work to be done before the generalized adoption of ISS policies by organizations becomes a reality. The conclusions of that work motivated the accomplishment of this study focused on the adoption of ISS policies by Portuguese Municipalities. Besides giving continuity to previous works, the selection of the Local Public Administration sector offers an interesting opportunity for the study of ISS. On the one hand, citizens increasingly look for quality public information services, and, on the other hand, Town Councils (the local government of municipalities) manipulate high volumes of very diverse information, which makes ISS efforts essential for the normal functioning and for the protection of personal data which they are trusted with. Additionally, choosing Public Administration organizations as the targets of research will contribute to a better understanding of the commonalities and differences between public and private sector organizations in the realm of information systems and in the specific field of ISS research.

In the face of the results obtained from the study carried out in the 308 Municipalities, the working proposition brought forward is that the present situation in the Portuguese Local Government represents a non-institutionalization of the adoption of ISS policies. This conception of the research problem prompted the application of Institutional Theory as a theoretical framework in order not only to better understand the reduced adoption of policies by the Municipalities but also to delineate actions which can enhance this adoption, i.e., which can enhance the institutionalization of ISS policies in the Portuguese Municipalities. Thus, the following two research questions were formulated in order to guide the research work:

Which factors condition the adoption of an ISS policy in the Portuguese Municipalities?

Which recommendations might be put forward so as to enhance the adoption of ISS policies by Portuguese Municipalities?

The answer to the first question aims to know the positive and negative conditioning factors influencing the adoption of an ISS policy by organizations. In the possession of these elements, it will be relevant to produce a set of recommendations which enable the adoption of that ISS control by organizations.

As far as structure is concerned, this work is organized as follows. After this introduction, Institutional Theory is briefly revised as the interpretive lens of this work. After this, the study which was carried out is described and its main results are presented. Based on the analysis of the results, a set of guidelines is suggested for the institutionalization of ISS policies. Finally, the main contributions of this paper are indicated, as well as its limitations and suggestions for future works.

2. Institutional Theory as an Interpretive Lens

Changes in technology and in the economy generate modifications in the organizational environment. In the face of this, the search for innovation represents one way for the survival of organizations. The success of the organization is then measured by the capacity to survive, change, and anticipate the market needs [Brown and Eisenhardt 1998]. Therefore, organizations gradually institutionalize organizational practices in order to face new realities, which cannot be faced using the previously existing organizational practices.

The Institutional Theory considers the processes through which structures (e.g., frameworks, rules, norms, and routines) are established as trustworthy guidelines for social behavior. Also, it accounts for the way these elements are created, spread, adopted, and adapted throughout time and space, as well as the way they fall into decline and disuse [Scott 2004]. Institutions may be conceived as high resilient social structures that enable and constrain the behavior of social actors and that provide stability and meaning to social life [DiMaggio and Powell 1991; North 1990; Scott 2008].

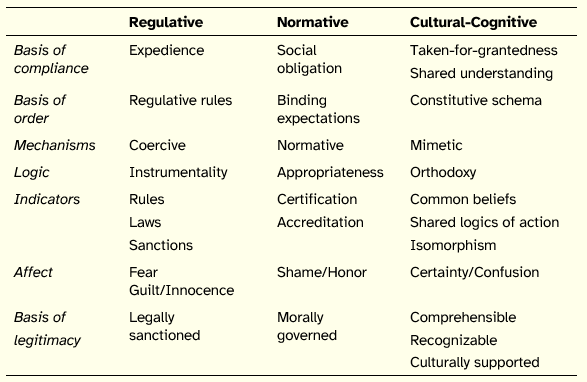

The Institutional Theory classifies into three pillars the way structures or mechanisms of diverse nature, which are essential for the creation of new institutions or for the change of existing institutions, can be created, maintained, altered, or destroyed. Those three pillars of institutions are the regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive pillars, and their main features are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Pillars of Institutions

Source: Scott [2008, p. 51]

The regulative pillar constrains and regulates behavior through formal rules, sanctions and punishments. Therefore, the legitimacy of actors’ actions is based on the compliance with the legally sanctioned instruments. In the normative pillar, emphasis is given to a deeper moral legitimating basis, in which values and norms are highlighted as elements capable of pressing organizational action, thus turning into a social obligation through daily use. The third pillar, the cultural-cognitive structures, sustains meanings which are shared among the actors about the regulative and normative structures, that is to say, about the reality which surrounds the actors while they continuously build and negotiate that social reality, within a context that includes symbolic, objective and external structures which offer guidance for understanding and action.

Just as it is possible to analyze the evolution of a certain institution within an organization, it is also possible to interpret evolutions in other levels of analysis, such as in industrial sectors and societies. Since its inception, Institutional Theory has been used to analyze and make sense of institutionalization processes in organizations, industries and societies. Viewed as projections of organizations in what concerns their information manipulating activities [Carvalho 2002], information systems have also constituted fertile ground for the application of Institutional Theory. Illustrative studies of this application are the works by Orlikowsky [1992], King et al. [1994], Premkumar et al. [1997], Chatterjee et al. [2002], Teo et al. [2003], Baptista [2009] and Bharati and Chaudhury [2012].

This study resorts to Institutional Theory to examine and classify the factors that influence the adoption of ISS policies by organizations. Our goal was to consolidate the main influencing factors from the organizational level of analysis located at each Town Council to the level of the Portuguese Local Government as a whole. The result of that consolidation forms the basis for the proposal of a set of guidelines aimed to enhance the institutionalization of ISS policies in Portuguese Local Government. Besides our stated immediate goal for this work, we are also responding to the challenge launched by Björck [2004] to use the theoretical lens of Institutional Theory to interpret ISS related issues. And for that matter, we argue that Institutional Theory may be of use not only to understand why organizations have adopted ISS policies, but also to shed a light on why a large number of organizations have still not institutionalized that routine. If we reach a better understanding for these two distinct situations, then we could, with the additional expectation of using the same theoretical lens, base a set of recommendations that may put organizations in the path of adopting ISS policies.

3. Description of the Study

In order to answer the first research question, a field study was carried out through face-to-face semi-structured interviews with the officials in charge of the information systems in the Town Councils, most of which had the position of Chief Information Officer.

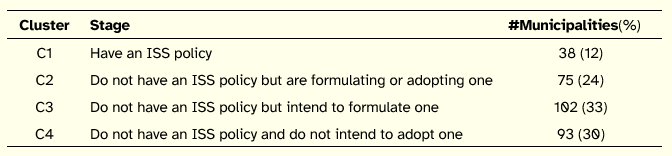

In regard to the adoption of an ISS policy by Municipalities we were able to identify four different stages of policy uptake, namely those Municipalities who have already adopted an ISS policy, the ones that do not have an ISS policy but are in the process of formulating such a document or are in the verge of adopting it, those that do not have an ISS policy but intend to formulate one and, finally, the ones that do not have an ISS policy and do not intend to adopt one. These stages allowed us to subdivide the 308 Municipalities into four clusters, as depicted in Table 2. As previously noted, we consider that currently the Portuguese Local Government, as a whole, has not institutionalized the adoption of ISS policies, although a minority of Municipalities has already initiated the institutionalization process.

Table 2: Clusters of ISS Policy Adoption

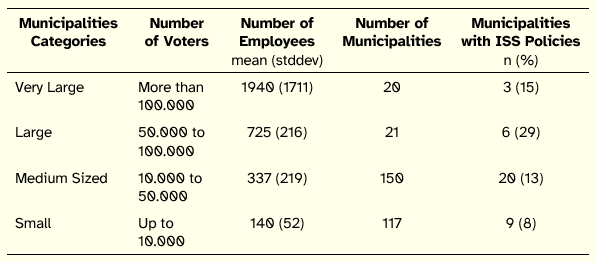

Besides the four clusters, the number of voters in each Municipality was also considered so as to translate the size and complexity of the corresponding Town Councils. Table 3 represents the distribution of the 308 Municipalities according to the number of voters. In the Table we also include information regarding the average number of employees by municipality category (the mean for all Town Councils is 393 employees).

Table 3: Distribution of Municipalities according to Size of the Electorate

In order to gather a wider and more complete panel of officials to be interviewed, the two criteria mentioned above were combined (cluster and size of the electorate). This way we expected to contact different realities and potential different visions regarding ISS, and at the same time to include into the analysis the eventual impact of organizational size and the amount of resources available on the efforts towards protecting information systems’ assets.

Altogether 44 municipal officials were interviewed, distributed equitably among the four clusters. Each cluster contributed with 11 interviews, with the respondents being randomly selected from each cluster. In terms of size of the electorate, that distribution comprised five very large municipalities, seven large municipalities, 27 medium sized municipalities, and five small municipalities. The average duration of the interviews was 40 minutes.

As far as process is concerned, the field study was developed through the following steps:

Elaborating the interviews guides–four guides were drawn, one for each cluster.

Elaborating the codebook–in order to guide the interview codification process, a codebook containing 49 codes was designed according to the previously defined interviews guides. The structuring of the codebook followed the model proposed by MacQueen et al. [1998], who have suggested that the following information should be associated to each code: the code name, a brief description, a detailed description, indication of when to use the code, indication of when not to use the code, and an example of application of the code.

Elaborating coding instructions–along with the codebook, a set of coding instructions was defined describing the procedures that operationalized the codification work.

Doing the interviews–all interviews were conducted face-to-face, in the facilities of the Town Halls, and they were audio recorded, after obtaining the interviewees authorization.

Transcribing the interviews–all interviews were fully transcribed.

Codifying the interviews–the codification of all interviews was done with the support of a data analysis application.

Analyzing results–after the interviews codification, the results were analyzed in the light of Institutional Theory, namely by consolidating a general list of factors, and afterwards by classifying them as follows in the next section.

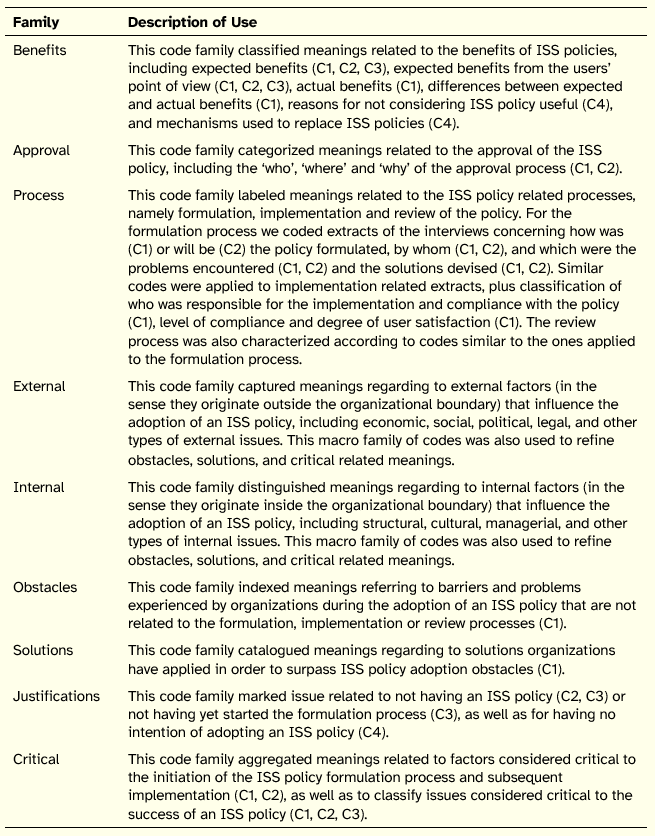

Given our decision to use Institutional Theory as an interpretative lens to assist in the understanding of why some organizations have adopted ISS policies and others have not, we elaborated the interview guides with pivotal questions according to the distinctive features of each cluster. Subsequently, we defined a set of codes that could help us analyze the content of the interviews from an Institutional Theory viewpoint. In Table 4 we list the main families of codes that composed our codebook, providing for each family a brief description of its use (when some codes only applied to particular clusters of organizations we signaled that by using Cx, where x denotes the number of the cluster as defined in Table 2).

Table 4: Families of Codes

4. Conditoning Factors

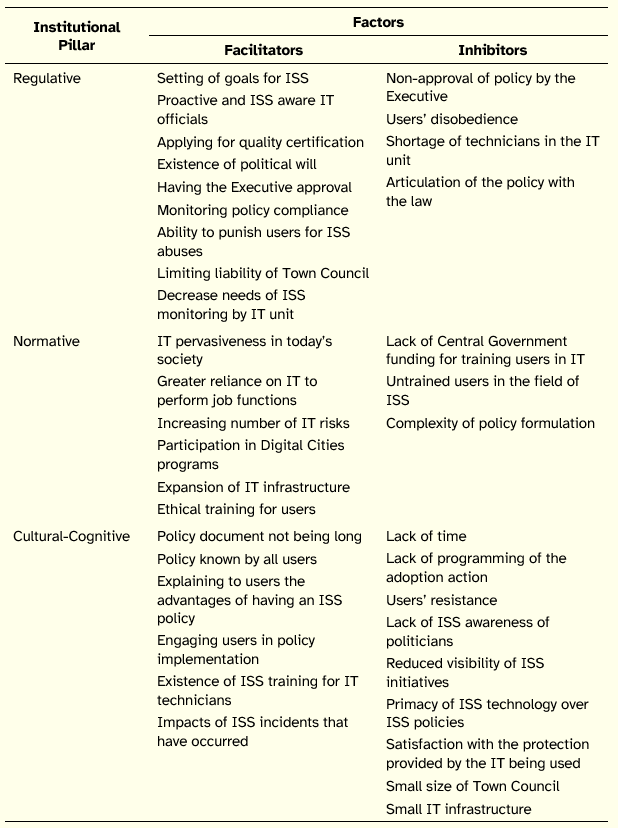

The analysis of the interviews led to the identification of various conditioning factors to the adoption of ISS policies by the Portuguese Municipalities. Part of these factors is positive, facilitating the adoption of such policies. Another part is negative, inhibiting the adoption of policies. According to the nature of the identified factors, it was possible to categorize them according to the three pillars of institutions, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Conditioning Factors in the Adoption of ISS Policies

At the regulative pillar, among the factors facilitating the adoption of ISS policies are a previous definition of goals for ISS (which shows that ISS was deliberately considered by the Town Council), proactive and ISS aware information technology (IT) officials (in the majority of municipalities the IT officials are the pivotal elements for the ISS initiatives), the application for quality certification (a number of municipalities were developing quality certification processes that, in order to obtain the certificate, required the adoption of an ISS policy), the existence of political will for ISS (without which any efforts to protect IS assets are doomed to failure, both due to lack of resources and to lack of superior sponsoring and authorization) and the policy document must have superior approval (which formalizes the adoption of the policy by the Town Council and shows the document legitimacy to users). Besides these factors, we found that interviewees considered monitoring policy compliance an important issue, since it signalized the importance of the policy determinations, along with the ability to punish users for ISS abuses, a situation that is only achievable if the Town Council has a formal document making explicit the allowed and forbidden behaviors of users in the realm of information manipulation activities. Two additional factors play an important role on the adoption of ISS policies by Municipalities, namely the intention to limit liability of the Town Council in ISS related issues and the expected decrease in the needs of ISS monitoring by the IT unit, releasing its technicians to other tasks.

At the normative pillar, the facilitating factors derive, fundamentally, from the Town Councils making part of the current organizational environment, where the pervasiveness of IT is paramount and the reliance of Town Councils employees on IT to perform their jobs keeps increasing. Thus, the need to deliberately consider the protection of IS should become a natural concern of the Town Councils, whose first formal step generally translates into the adoption of an ISS policy. This is reinforced by IT officials recognizing an increase in the number of IT risks, prompting them to take a more systematic approach in protecting IS assets. A similar pattern to the involvement in quality certification processes was found, namely the participation in Digital Cities programs, where Town Councils may voluntarily associate with. Among the initiatives that the participating Municipalities agreed to undertake is the adoption of an ISS policy. The expansion of IT infrastructures (be it by internal acquisition of hardware and software, or by outsourcing services or equipment) not only enables a better information protection (new servers, backup systems, anti-virus) but also works as a booster to the formulation of the ISS policies themselves (the underlying reasoning is that using more complex, diversified, and capable IT systems results in greater expectations and obligations to consider ISS). Finally, the existence of ethical training for users is pointed out by some interviewees as a relevant facilitator for the adoption of ISS policies, since it makes users aware of the main directives for an ethical behavior in the domain of ISS, favoring the adoption of an ISS policy by all users.

At the cultural-cognitive pillar, and still concerning the facilitating factors, the focus is mainly on people’s role in their daily adoption of the policy. The factors highlighted were the need for the policy document not to be extensive (under penalty of diluting the essential among the accessory and overloading users cognitively), for the policy to be known by all users, in order to which it must be made available and transmitted by the intermediate management officials; showing users the advantages of complying with the policy (as or even more important than knowing how to use a certain technology, users must know and understand the goals of ISS which are at the base of its adoption), commitment to the implementation of the policy (in order to avoid that the policy goes unheeded due to lack of the resources needed for its achievement) and IT technicians must be trained (so that they are skilled in the domain of ISS and thus are able to give a comprehensive answer to the implementation needs implied in the adoption of the policy). One last factor regards the impacts of ISS incidents that have occurred in the Town Council in the past. The consequences of these incidents play an important role in increasing the awareness of users to ISS, as well as garnering the support of the Executive for the ISS program.

As far as the inhibiting factors are concerned, in what regards the regulative pillar, and besides the non-approval of the policy by the Executive (reason enough to prevent the adoption of the policy), other factors are highlighted such as users’ disobedience, shortage of technicians in the IT unit, and articulation of the policy with the law. Indeed, converting mere recommendations for ISS into normative acts of imperative character, followed by the application of sanctions or restrictions for those who do not comply with them, can be strong inhibiting factors in the adoption of ISS policies, leading to users’ disobedience. In various Municipalities this disobedience stemmed from a concern among users that the policy was being used as an instrument of surveillance and monitoring of users’ behaviors. The scarcity of human resources in the IT unit presents an obstacle for a number of Town Councils revealing that it may be hard to put the ISS concern in the Town Councils’ political agenda or they simply are not able to allocate expertise to make ISS programs evolve. The aforementioned factor of articulating the policy with the law results from the difficulty that some Town Councils face in aligning the provisions they want to instill in the policies with the determinations of the law, namely regarding compliance with privacy and protection of personal data requirements.

At the normative pillar, the inhibiting factors are related to conditions largely transversal to the Portuguese Municipalities that hamper the adoption of ISS policies. Regarding training, the interviewees noticed the lack of Central Government funding for training users in IT, which is adverse to the integral exploitation of IT capacities, and the generic situation of users being untrained in ISS matters, making it difficult for users to assess and recognize the risks of IT and the potential counterproductive effects of their behaviors in terms of IS protection. A third observation advanced by the majority of the interviewees was the view that ISS policy formulation is a complex process, requiring specialized know-how and experience in order to achieve a written document well attuned to the specificities of each Town Council.

Finally, in the set of inhibiting factors and in what concerns the cultural-cognitive pillar, we found five sets of factors. The first set relates to the secondary importance of ISS in some Town Councils, manifested in lack of time for considering ISS issues in face of the need to address pressing daily IT issues, and lack of programming of the ISS policy adoption action. The second set concerns users’ resistance, a phenomenon that generally has to be taken into account when there are changes in users’ working routines, and the adoption of a policy is no exception, usually requiring the abandonment of old habits and the assimilation of new ones. Indeed, interviewees observed that resistance from users would drop as soon as the ISS policy promoters were able to demonstrate that information would be more secure by adopting the policy. The third set of factors concerns the conceptions regarding ISS held by the Town Councils’ politicians, who lack awareness of ISS and that do not recognize the impact (namely in terms of image) of ISS initiatives, mainly due to their reduced visibility and support nature (it is worth mentioning that these perceptions are common when the organization did not experience any serious security breach, situation that apparently relegates ISS to a non-strategic concern in some of the Town Councils). The fourth set of factors consists of beliefs maintained by some IT units conveyed by the opinion that their organizations have enough IT to guaranty an adequate ISS level, as well as the primacy given to ISS technology over ISS policies, which make the latter redundant in face of the former. As a result, they argue there is no need for additional IS protection actions, namely adopting ISS policies. The fifth set of factors concerns size. We found that two explanations provided by interviewees pertaining to Municipalities that did not adopt an ISS policy were the small size of the Town Council and the small IT infrastructure in use, reasoning there would be no need for adopting an ISS policy.

5. Guidelines of the Information Systems Security Policies Institutionalization

Considering the identified factors influencing the adoption of ISS policies, we argue that the institutionalization of ISS policies in Portuguese Municipalities will be a process of several stages, shaped by pressures of regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive nature.

With respect to the regulative pillar, we suggest the formulation of an ISS policy based on a generic model subsequently adapted to each Municipality. Such policy must have superior approval, and must be followed by a policy implementation plan and the establishment of sanctions and punishments for users who, without a justification, do not comply with its provisions. The existence of a generic model for the ISS policy document for Town Councils, perhaps conceived under the aegis of the National Association of Municipalities, may be an important tool to break the initial inertia of the formulation process, mitigating the difficulties that some Councils might experience due to resources limitation or lack of technical knowledge for the formulation of a policy. The generic model of the policy must include a set of directives which guide users towards information protection and the secure use of IT.

With regard to the normative pillar, the policy legitimization in the daily organizational activity must be boosted. For this, we suggest the identification of power users who, through their example, can serve as models for other users, as well as the definition of an awareness program concerning ISS aimed at users. Establishing compensations for users who behave according to the ISS policy provisions will also be a means to highlight the values and norms underlying ISS. An ISS certification process launched by the Central Government and targeting Municipalities can also signal the priority given to ISS.

As far as the cultural-cognitive pillar is concerned, the most immediate measure which could be adopted is programming training sessions in the scope of ISS, in which users are trained to have behaviors which protect IS. These sessions should not follow a lecturing training model, but rather a participative model, in which the good ISS practices can be applied to users’ daily tasks, and in which they can discuss and challenge the ISS provisions that they consider less effective or that conflict with their other attributions. The creation of forums of free discussion of the ISS determinations impact may also help to enhance an ISS culture, in which all feel involved and in which the ISS success can be perceived as a responsibility shared by all. Of the same importance is to widen the adaptation of the generic model mentioned above to the several Town Council pressure groups. This way, it will be possible to create, from the beginning, a sense of property over the ISS policy, thus avoiding the perception of it as a top-down directive. The dissemination of successful cases of adoption of ISS policies in certain Municipalities may work as a mimetic mechanism for other Municipalities, thus influencing their predisposition to adopt ISS new rules and procedures.

The conjunction of these actions to enhance the adoption of ISS policies in Portuguese Municipalities can be summarized in six essential points: defined, approved, published, communicated, understood, and evaluated. The ISS policy must be correctly defined and written in order to meet the intended organization’s characteristics, according to its nature, target-public, goals, and culture. Superior approval is essential to show superior commitment, thus making its implementation more effective and legitimating its acceptance by users. The document must be published and communicated to all users. Making sure that users understand the provisions and reasons underlying the ISS policy is essential for compliance. In order to maintain the policy appropriateness and updating, the policy must be evaluated regularly and modified when necessary.

The strategy based on agents is a way to enhance the institutionalization of ISS policies in Municipalities. The main agents who may play an active part in this process are the National Association of Municipalities, the Town Council Executive/Municipal Assembly and the IT unit officials.

The first agent mentioned is the one who interacts the most directly with Municipalities at a national level. Although this association does not have imposing power of norms or regulations, it is the one that most easily communicates with the Town Councils and therefore can raise awareness towards the importance of adopting ISS policies, as well as suggest models which can be adapted to the various Portuguese municipalities. Its action would, therefore, fit essentially in the normative pillar.

The second agent also plays an essential part in the adoption of an ISS policy. Without the involvement of the Town Council Executive or Municipal Assembly in the process of adoption of a policy, from its formulation to its revision, including its implementation, policy adoption will not become a reality. This agent will primarily act within the regulative pillar.

The officials in charge of the Town Councils’ IT units are normally the main agents boosting ISS policies adoption initiatives. These agents need to build bridges among the several actors in the ISS policies adoption process (politicians, technicians, and users), in order to find a balance between purely technical views and business and management views and concerns. Due to their knowledge in the ISS domain and of the reality of the Town Council in which they operate, and as they are usually the ones in charge of programming IT management and improvement initiatives, they play a central role in the cultural-cognitive pillar.

6. Conclusion

The improvement of IS protection levels in organizations depends on the implementation of a set of ISS controls, among which ISS policies play an essential part. The importance given to this security control by literature does not always extend to organizations, where often such a document does not exist or despite existing, has no reflection whatsoever in the organizations’ activities.

This study identified a set of factors which condition the adoption of ISS policies in Portuguese Municipalities. Besides this contribution, this paper brought forward guidelines which are believed to enhance the institutionalization of ISS policies in the organizational area of Local Government in Portugal. We also argue that the use of Institutional Theory as a support to the interpretation of the adoption stage of ISS policies by organizations and as a support to the projection of guidelines which enhance the institutionalization of these ISS controls in organizations represents a promising means for research.

The delimitation of the study to the Portuguese reality represents one of its limitations. A further limitation regards the professionals who were interviewed, since we restricted the collection of views to those in charge of the Town Councils’ information systems.

As a future work, it would be relevant to assess the adoption level of ISS policies in other sectors of activity, in other countries and in different cultures. Additionally, it would be important to look into the factors which might have facilitated or inhibited the adoption of policies in those contexts, taking into consideration the views of several stakeholders, namely chief information officers, information technology technicians, top and line managers, and users. The accumulation of knowledge on the adoption of policies in different types of organizations would represent a privileged way for the construction of a theory on ISS policies.

References

Baptista, J. (2009). Institutionalisation as a Process of Interplay between Technology and Its Organisational Context of Use. Journal of Information Technology 24(4), 305–320.

Bharati, P. and A. Chaudhury (2012). Technology Assimilation Across the Value Chain: An Empirical Study of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Information Resources Management Journal 25(1), 38–60.

Björck, F. (2004). Institutional Theory: A New Perspective for Research into IS/IT Security in Organisations. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1–5. Hawaii.

Bowen, P., J. Hash and M. Wilson (2007). Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers—NIST SP 800-100. Gaithersburg, MD (USA).

Brown, S.L. and K. M. Eisenhardt (1998). Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Bulgurcu, B., H. Cavusoglu and I. Benbasat (2010). Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical Study of Rationality-based Beliefs and Information Security Awareness. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 523–548.

Carvalho, J. Á. (2002). Strategies to Deal with Complexity in Information Systems Development. Proceedings of the ISAS-CSI 2002—6th World Multiconference on Systems, Cybernetics and Informatics, 42–47. Orlando, FL (USA).

Chatterjee, D., R. Grewal and V. Sambamurthy (2002). Shaping up for E-commerce: Institutional Enablers of the Organizational Assimilation of Web Technologies. MIS Quarterly 26 (2), 65–89.

DiMaggio, P. and W. Powell (1991). Introduction. In Powell, W.W. and P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, 1–38. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Höne, K. and J. Eloff (2002). Information security policy—what do international information security standards say? Computers & Security 21(5), 402–409.

Ifinedo, P. (2011). An Exploratory Study of the Relationships between Selected Contextual Factors and Information Security Concerns in Global Financial Services Institutions. Journal of Information Security and Privacy 7(1), 25–49.

ISO/IEC (2013). ISO/IEC 27002:2013—Information technology—Security techniques—Code of practice for information security controls. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

King, C., E. Osmanoglu and C. Dalton (2001). Security Architecture: Design, Deployment, and Operations. Berkeley: Osborne/McGraw-Hill.

King, J. L., V. Gurbaxani, K. L. Kraemer, F. W. McFarlan, K. S. Raman and C. S. Yap (1994). Institutional Factors in Information Technology Innovation. Information Systems Research 5(2), 139–169.

Lopes, I.M. and F. de Sá-Soares (2010). Information Systems Security Policies: A Survey in Portuguese Public Administration. Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Information Systems 2010, 61–69. Porto (Portugal).

MacQueen, K. M., E. McLellan, K. Kay and B. Milstein (1998). Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods 10(2), 31–36.

North, D. C., 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Orlikowski, W. J. (1992). The Duality of Technology: Rethinking the Concept of Technology in Organizations. Organization Science 3(3), 398–426.

Peltier, T. R. (2002). Information Security Policies, Procedures, and Standards: Guidelines for Effective Information Security Management. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications.

Premkumar, G., K. Ramamurthy and M. Crum (1997). Determinants of EDI Adoption in the Transportation Industry. European Journal of Information Systems 6(2), 107–121.

de Sá-Soares, F. (2005). A Theory of Action Interpretation of Information Systems Security. PhD Dissertation. University of Minho, Guimarães (Portugal).

Scott, W. (2004). Institutional Theory. Encyclopedia of Social Theory, 408–414. Thousand Oaks:SAGE.

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests, third edition. Thousand Oaks:SAGE.

Shorten, B. (2004). Information Security Policies from the Ground Up. Information Security Management Handbook, 5th edition, 917–924. Boca Raton: Auerbach.

Soares, D. (2009). Information Systems Interoperability in Public Administration. PhD Dissertation. University of Minho, Guimarães (Portugal).

Teo, H., K. K. Wei and I. Benbasat (2003). Predicting Intention to Adopt Interorganizational Linkages: An Institutional Perspective. MIS Quarterly 27(1), 19–49.

Tolbert, P. S. and L. G. Zucker (1996). The institutionalization of institutional theory. Handbook of Organization Studies. London: Sage.