Original source publication: Lopes, I. M. and F. de Sá-Soares (2013). Applying Action Research in the Adoption of Information Systems Security Policies. In Ramos, I. and A. Mesquita (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies, 219–226. Guimarães (Portugal). Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited, ISBN: 978-1-909507-30-2.

Applying Action Research in the Adoption of Information Systems Security Policies

a Departamento de Informática e Comunicações, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Bragança, Portugal

b Centro Algoritmi, Universidade do Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

Information Systems Security (ISS) is a critical issue for a wide range of organizations. This paper focuses on organizations belonging to a particular sector, namely Local Public Administration, where public and personal information must be protected by those in charge, and where there must be a concern to view security as a priority. There are several measures which can be implemented in order to ensure the effective protection of information assets, among which stands out the adoption of ISS policies. A recent census concluded that among the 308 Town Councils in Portugal, only 38 indicated to have an ISS policy. The conclusion drawn from that study was that the adoption of ISS policies has not become a reality yet. As an attempt to mitigate this fact, an academic-practitioner collaboration effort was established regarding the implementation of ISS policies in three Town Councils. These interventions were conceived as Action Research projects.

This article aims to constitute an empirical study on the applicability of the Action Research method in information systems, more specifically through the implementation of an ISS policy in Town Councils where previous attempts to adopt a policy have failed. The research question we intend to answer is to what extent this research method is adequate to reach the proposed goal.

The results of the study suggest that Action Research is a promising means for the institutionalization of ISS policies adoption. It can both act as a research method, improving the understanding among researchers about the issues that hinder such adoption, and as a change method, assisting practitioners to overcome barriers that have prevented the implementation of ISS policies.

Keywords: Action Research; Information Systems Security Policies; Information Systems Security Policy Adoption; Information Security

1. Adoption of Information Systems Security Policies

Nowadays, Information Systems Security (ISS) is a critical issue for a wide range of organizations. The centrality of information in the operations and management of organizations raises concerns regarding the protection of information systems’ (IS) assets, including hardware, software, data, processes, and people.

In order to adopt an ISS policy, an organization must follow a sequence of steps, beginning by writing the policy, followed by its implementation, and then, at predefined moments or when circumstances require it, by reviewing its provisions, which may prompt modifications in the policy. Indeed, this sequence of steps may be viewed as a cycle of formulation—implementation—revision of the policy.

Although there is a considerable agreement in the literature regarding the main role played by ISS policies, there is evidence that organizations often fail in the adoption of this security control. Focusing their attention in a particular type of organizations, namely Local Public Administration, Lopes and de Sá-Soares [2010] surveyed the 308 Town Councils in Portugal to find out that only 38 (12%) indicated to have an ISS policy. However, it was also found that 177 (66%) of the respondents had thought or were considering formulating an ISS policy, but were not yet able to reach the state of having adopted that security measure. The conclusion drawn from the study was that the adoption of ISS policies has not become a reality yet, suggesting there is still a long way to go before the institutionalization of ISS policies measure that group of organizations.

This state of affairs promptly raised several questions to the researchers, such as the reasons for such a low level of adoption and the obstacles that have prevented the Town Councils to successfully apply ISS policies. Shortly after the conclusion of that survey, the heads of the IT departments of several municipalities that still hadn’t adopted an ISS policy contacted the first author of this paper requesting assistance for the implementation of an ISS policy. Although the specialized literature provided general guidelines regarding the content for the policy documents as well as several recommendations for writing, implementing, and reviewing ISS policies, the authors were faced with a methodological decision, i.e., how to do it. After considering several alternatives, such as promoting workshops or just plain consultation work, a decision was made to propose the Town Councils an Action Research (AR) intervention.

This article aims to constitute an empirical study on the applicability of the Action Research method in the field of IS, more specifically analyzing the implementation of ISS policies in Town Councils where previous attempts to adopt a policy had failed, according to the tenets advocated by AR. Hence, the research question that guided this work was to answer to what extent AR methodology is adequate to support the process leading to the adoption of ISS policies.

Structurally, this paper is organized as follows. After this contextualization of the subject, we review the main tenets and characteristics of AR, in general and in the field of IS. Then, we describe the collaborative efforts that were promoted to adopt ISS policies in three Town Councils, followed by a discussion. Finally, we enumerate the papers’ main contribution, limitations, and suggestions for future work.

2. Perspectives on Action Research

The description of a research method application, as well as the lessons learned from that application, benefit from several previous clarifications. Among them are the way researchers understand the research method, the indication of the method’s main characteristics, and the explanation of how the method applies to the targeted practice context.

Although different authors may have different perspectives concerning the application of AR, there is consensus with respect to the method general architecture. Briefly, AR starts with the detection of a problem, from which changes are projected in order to solve the problem. This process has a cyclic nature and, once it is applied to organizations or other social groups, it will hardly be seen as definitely solved. It will rather suffer changes and require new interventions. As a result, AR is considered a change-oriented methodological approach: it is not restricted simply to the understanding of phenomena but it deliberately aims at changing those phenomena.

Although the exact characterization of AR varies with the authors, Dick [2000] isolated a set of aspects which seem to be consensual among authors:

It acts on an existing situation with the dual aim of improving it and expanding the knowledge on the subject.

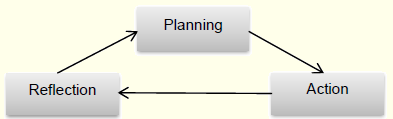

It possesses a cyclic nature: a number of steps are performed repeatedly. The cycle varies with the author but, at least, it includes the steps: Planning—Action—Reflection.

It admits the participation of the research subjects, although this condition is not unanimously considered as mandatory.

It possesses a reflexive nature: a critical reflection on the research process itself as well as on the results obtained is an important part of each cycle.

It is predominantly qualitative, although quantifications are possible in some situations.

The AR method completes an interactive cycle made up of a series of stages whose number and designation depend on the author. Considering the review of literature carried out, three illustrative models were identified, varying in terms of structural complexity.

Cunha and Figueiredo [2002] present a model adapted from Dick [1992], that includes three stages: Planning, Action and Reflection, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Three Steps AR Cycle

Source: Cunha and Figueiredo [2002]

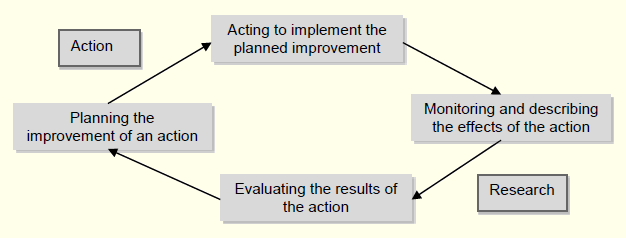

Tripp [2005] conceives the execution of AR in four phases: Planning, Acting, Describing, and Evaluating, as represented in Figure 2. In AR a change is planned, described and evaluated viewing the improvement of an action. Throughout the process, further learning takes place, both concerning the action and the research itself.

Figure 2: Four Steps AR Cycle

Source: Tripp [2005]

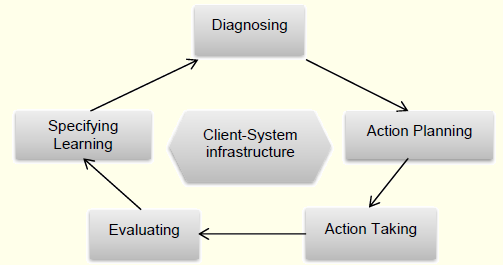

Associated with each of the stages included in this model are the following goals:

Diagnosing—Identification of a problematic situation, related to the need of change of a certain organization;

Action Planning—Specification of the organizational actions which must be undertaken in order to solve the problems identified in the diagnostic;

Action Taking—Implementation of the actions previously planned which will supposedly lead to changes;

Evaluating—Assessment of the intended goals achievement and solution;

Specifying Learning—Specification of the knowledge acquired with the introduced change. Although this stage appears as the last in the scheme, it consists of a permanent process.

Figure 3: Five Steps AR Cycle

Source: Susman and Evered [1978]

3. Action Research Applied to Information Systems

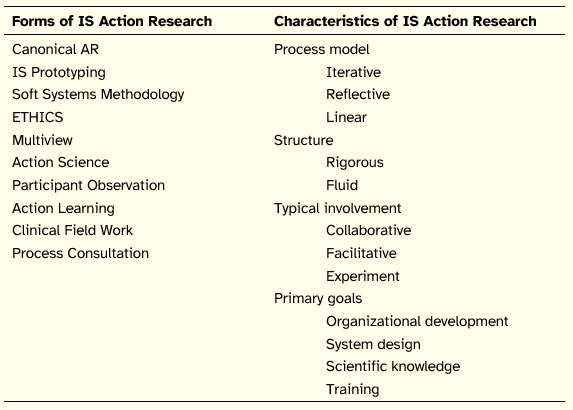

According to Baskerville [1999], AR was explicitly introduced in the IS community as a pure research method by Wood-Harper [1985]. Reviewing the uses of AR in IS, Baskerville and Wood-Harper [1998] were able to identify ten forms of AR in IS, differing in terms of several characteristics, which were organized into four groups: Process model; Structure; Typical involvement; and Primary goals. Table 1 shows these forms and characteristics.

Table 1: IS Action Research Forms and Characteristics

Adapted from Baskerville and Wood-Harper [1998]

From the exposed structures on works carried out in the field of IS using AR, we can see the variety of practices intervened, as well as the different types these interventions have assumed from the methodological point of view.

In the context of qualitative research in IS, Estay and Pastor [2000] consider AR operates over two realities, a scientific/academic one and a practical one. Thus, two different main types of AR cycles can be identified:

Cycles looking to solve problems in IS projects: These projects frequently consist of developing an IT artifact, with the researcher focusing on the solution of specific IS development problems. In this case, the purpose of AR is the creation of knowledge useful to the subjects and the improvement of a certain practice in which they are involved. The method is applied to build models, theories and knowledge, but in a way that is informed and biased by the reality upon which it is intended to act. In this cycle, the interest in solving a specific problem generates interest in researching the practice associated with that problem.

Cycles looking to inquiry in research projects: These projects are intentional research efforts in search of a result, in which AR acts as a structuring working method and as a reason for approaching a certain reality with the aim of testing a theory or hypothesis. In this case, the primary intention is to produce new knowledge in the field of IS, enabling the improvement of the researchers themselves. In this cycle, the interest in researching generates the interest in solving specific problems.

4. Action Research Applied to the Adoption of Information Systems Security Policies

The option for AR as the fundamental methodological guidance for the ISS policy adoption process resulted from the assumption of a set of propositions, partly supported in the literature and partly stemming from the results of the survey previously mentioned.

Given the reported difficulties of formulating a policy, as well as the evidence regarding the resistance of users on observing the policy, a joint, collaborative effort was the preferred way to move forward. By involving researchers and practitioners in a dialogue, we hoped to be able to transfer some best practices and theoretical knowledge to the users, while users explained the context factors that may facilitate or inhibit the success of the ISS policy and elaborate on their specific requirements in terms of IS protection.

It was also hoped that the cyclical structure of AR could better capture the advocated steps for the adoption of ISS policies, from formulation, to implementation, and then to revision. It would be easy to make that sequence of steps as a natural progression, wherein after its culmination, a new cycle of formulation, implementation and revision of ISS policies could be triggered. Underlying this cycle would be a learning process, where users and researchers could enhance the chances of learning what was working as expected, and what fell short or was counterproductive.

As the cycle of AR starts with the detection of a problem, the perception of such problem was clear in this study, namely the low level of ISS policies adoption by Portuguese City Councils.

After detecting this problem, intervention projects were started in three City Councils, aiming the introduction of changes towards the adoption of ISS policies. The whole process was structured according to the model proposed by Susman and Evered [1978] (cf. Figure 3).

In the first stage—Diagnosing—a problematic situation was identified, namely the non-adoption of an ISS policy by the City Council. This situation was made worse by the fact that the problem had been isolated previously and the head of the IT department had not been able to invert that situation. In other words, although the problem was known and assumed, the organizations had not been able to create the context to change the situation. This finding reinforced the conviction that AR might prove to be particularly appropriate to change the ongoing practice.

The first author came into contact with the reality of the three City Councils, starting her intervention by meeting the head of the IT department, and immediately trying to identify the reasons for not having managed to implement an ISS policy previously.

In one of the cases, the main reason was that they had not found any ISS policy model that they could adapt to the City Council reality. In another case, there had been some resistance from a council executive regarding the adoption of an ISS policy. In the third case, it was due to the fact that the ISS policy document had been made available on the Council intranet by the IS function, without being approved by the executive and therefore, the implementation consisted only on making the document available online without any other type of contract with the users of the City Council IS.

Besides the identification of the problem and the reasons inherent to the previous adoption failures, it was also during this stage that the real need for an ISS policy in the City Council was assessed. It was consensual that City Councils must stop worrying only about crackers’ attacks or about the implementation of firewalls or anti-virus, and start focusing on the creation of an ISS policy which can promote not only the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information, but also the responsibility, integrity, trust, and ethics towards information.

In the second stage—Action Planning—the organizational actions which must be executed to solve the problems identified in the diagnostic were specified. This process started by drawing the ISS policy document. The first author and the City Council IT Department Head started by assessing whether one policy would be enough or more than one would have to be drawn. We studied the possibility of drawing two policies, one aimed at the IT technicians and another at the users. However, bearing in mind that technicians are also users, although with different specifications, we chose to write only one broader policy document. We planned to draw the policy based on a model proposed by the first author and adapted to each City Council following the indications of elements from the IT department.

In the third stage—Action Taking—the planned actions were implemented, in the hope that these would lead to a change in the organization. In the face of the risk that ISS policies may not respond to the ISS requirements of an organization if they become obsolete due to changes in the business or threats to which the organization is submitted, some factors, such as auditing, were included in the implementation stage, in order to allow an assessment of the conformity with what was defined in the policy. The implementation also considered the management of incidents which, besides treating ISS incidents, enables to verify whether the policy manages to respond to the incidents or on the contrary, it does not include some important aspect, thus resulting in the need to implement the policy again or review its formulation. Depending on the importance or severity of the incidents or unconformities detected, relevant elements would be available for an eventual reformulation. To a certain degree, it is possible to draw a parallel between the integration of these audit and incident management tools and the subsequent sages of AR, as they enable an easier evaluation of the implemented actions, and might be useful to launch new AR cycles viewing the practical improvement of the implemented ISS policies.

In the fourth stage—Evaluating—we assessed the achievement of the intended goals of the ISS policy implementation. This evaluation required a review of the policy, which must take place periodically and especially whenever significant changes occur, in order to guarantee that the policy continues to meet the goals for which it was adopted. The evaluation was carried out by assessing the users’ compliance with the rules set by the policy. The subsequent modification of the policy was not found necessary for the time being.

The last stage—Specifying Learning—concludes the cycle, although in fact, this stage accompanies the whole process cycle of AR. The learning which took place throughout the whole cycle worked as a starting point to a new planning and, therefore, to the beginning of a new cycle sequence.

5. Discussion

The implementation of an ISS policy following the AR method was aimed at the construction of a solution to generate new knowledge, which was useful to the participants, on how to implement an ISS policy and improve its practice through successive evaluations and associated changes when necessary. At the same time that researchers cooperate in that process, they also aimed to add to accumulated knowledge, trying to understand the hindrances faced by organizations in the process of ISS policy adoption and to investigate the effectiveness of initiatives put on practice to overcome those difficulties. By participating in several of those processes, the research team collected evidence that may prove useful on projecting future interventions in other organizations of the same type. This dual interest of researchers—helping to change the specific context of practice (Action) and adding to the general knowledge of the ISS policy adoption process (Research)—raises some questions. Since the intervention is based on a cooperative structure, and since the control of the intervention by researchers is limited, the clear articulation and negotiation of the goals, views, and interests of the two groups of participants is particularly relevant.

In the present application of AR, these aspects were born in mind so as to guarantee higher accuracy and validity as well as lower limitations concerning the conclusions obtained in general. There was an effort to not manipulate or control, but to present users with alternative solutions, to draw their attention to issues that may go unnoticed or that although problematic for the users, should be addressed. Similarly, particular attention was devoted to the situational factors that characterize the context of practice, both in terms of work routines and of security actions that users have to counterbalance.

Given the collaborative nature of this study, the insights of the participating researcher were often debated and brought to reflection in order to produce a shared understanding that led to the change. Indeed, it was not intended that the researcher would unilaterally propose a change plan, but to build such a plan with the other actors involved in the transformation, namely the Town Council IT Departments.

The organizational culture of the Town Council and the level of training of its IT Department technicians play an important role in the implementation of an ISS policy, both in terms of awareness and training sessions required and in terms of users’ resistance to the provisions of the policy. Also, the size of the Town Council dictated how the policy document was disseminated among IS users.

The most critical aspect in the adoption of an ISS policy by a Town Council is the ISS awareness level of its executives. This is a paramount factor for explaining delays or blockages in the adoption, as well as processes that lead to a quick adoption of a policy.

In all three interventions, the actors believed that having an ISS policy model they could adapt to their reality increased the chances of successfully implementing an ISS policy.

Among the cases of application studied, we found evidence that the adoption of ISS measures, namely policies, must go beyond the implementation of hardware or software devices which protect what is stored in the organization databases and files and which, quite often, do not offer the necessary or expected security due to functioning, parameterization or installation flaws [Peltier 2002]. Besides the technological component, the human element constitutes the core of ISS. The difficulty in managing that element and in making it the main responsible for an effective protection of information assets is what makes ISS one of the most difficult and arduous aspects of many organizations management.

The institutionalization of ISS policies implies that the users observe the provisions of these policies on a daily basis, or, not of less importance, that they identify the aspects of the policy which lead to a lower protection level. By contemplating the specificities of each organization and by promoting the cooperation among researchers and users regarding the projection of actions which will affect them, AR acts both as a research and change method particularly promising for the adoption of ISS policies. On the one hand, it helps researchers understand the usefulness and limitations of the existing knowledge, opening new avenues to a better understanding of the ISS policies adoption phenomenon. On the other hand, and as a change method, it enhances the sense of property and co-responsibility of those who need to put into practice or review the procedures set in the ISS policies on a daily basis.

Situating the interventions according to the classification presented in Table 1, the studies configure canonical AR projects, grounded in an iterative process model guided by a rigorous structure, with the participating researcher playing a facilitative role, and having organizational development as their primary goal in the form of adopted ISS policies.

6. Conclusion

This study involved three City Councils through direct contact with the correspondent IT departments and indirect contact with the municipal executive as well as the users of the municipality IS. This work reports on the use and appropriateness of AR applied to the adoption of ISS policies, thus contributing as an empirical study on the application of that method in the field of IS.

This research work presents limitations, namely with respect to the number of City Councils involved. Although we believe that the study carried out in the three City Councils generated enough data to serve the goal of the work, we also believe that a larger number might result in a more sustained set of data. Nevertheless, we highlight that the application of the action research method requires the researcher’s direct involvement, thus requiring a substantial amount of time.

Another limitation of this work is related to the delimitation of the study within an organizational sector and a specific national reality.

Among the works which might be carried out in the future, we highlight the proposal of an ISS policy model, thought up for the national municipal reality, and which may work as a starting point to the adoption of ISS policies by the City Councils, so as to invert the reduced number of policies existent in the Portuguese City Councils. The provision of that document by the City Councils and the use of AR as a method for planning and promoting change, in which researchers and practitioners project actions, implement them, and evaluate their impacts, may prove to be two important tools for the institutionalization of ISS policies in organizations.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by FEDER funds through Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade—COMPETE and National funds by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia under Project FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-022674.

References

Baskerville, R. (1999). Investigating Information Systems with Action Research. Communications of the AIS 2(19), 1–32.

Baskerville, R. and A. T. Wood-Harper (1998). Diversity in Information Systems Action Research Methods. European Journal of Information Systems 7(2), 90–107.

Baskerville, R. and A. T. Wood-Harper (1996). A Critical Perspective on Action Research as a Method for Information Systems Research. Journal of Information Technology 3(11), 235–246.

Cunha, P. R. and A. D. Figueiredo (2002). Action Research and Critical Rationalism: a Virtuous Marriage. Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Information Systems. Gdansk (Poland).

Dick, B. (2000). A beginner’s guide to action research. Southern Cross University, Australia. http://www.scu.edu.au/schools/gcm/ar/arp/guide.html

Dick, B. (1992). Qualitative action research: improving the rigour and economy. Proceedings of the Second World Congress on Action Learning. University of Queensland. Brisbane (Australia).

Estay, C. and P. Pastor (2000). Towards a Project Structure for Action-Research in Information Systems. Proceedings of the 10th Annual Business and Information Technology Conference. Manchester.

Jönsson, S. (1991). Action Research. In Nissen, H.-E., H. Klein and R. Hirschheim (Eds.),Information Systems Research: Contemporary Approaches & Emergent Traditions, 371–396. Amsterdam:North-Holland.

Kemmis, S. and R. McTaggart (Eds.) (1988). The Action Research Planner, third edition. Deakin University Press, Victoria.

Lopes, I. and F. de Sá-Soares (2010). Information Systems Security Policies: A Survey in Portuguese Public Administration. Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference on Information Systems. Porto.

Peltier, T. R. (2002). Information Security Policies, Procedures, and Standards: Guidelines for Effective Information Security Management. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications.

Rapoport, R. N. (1970). Three Dilemmas in Action Research. Human Relations 23(4), 499–513.

de Sá-Soares, F. (2005). A Theory of Action Interpretation of Information Systems Security. PhD Thesis. University of Minho, Guimarães.

Susman, G. and R. Evered (1978). An Assessment of the Scientific Merits of Action Research. Administrative Science Quarterly 23(4), 582–603.

Tripp, D. (2005). Pesquisa-ação: uma introdução metodológica. Educação e Pesquisa 31(3), 443–466.

Wood-Harper, T. (1985). Research Methods in Information Systems: Using Action Research. In Mumford, E., R. Hirschheim, G. Fitzgerald and T. Wood-Harper (Eds.), Research Methods in Information Systems, 169–191. Amsterdam: North-Holland.