Original source publication: Lopes, I. M. and F. de Sá-Soares (2012). Information Security Policies: A Content Analysis. Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems 2012, Paper 146. Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam).

The final publication is available here.

Information Security Policies: A Content Analysis

a Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Portugal

b University of Minho, Centre Algoritmi, Portugal

Abstract

Among information security controls, the literature gives a central role to information security policies. However, there is a reduced number of empirical studies about the features and components of information security policies. This research aims to contribute to fill this gap. It presents a synthesis of the literature on information security policies content and it characterizes 25 City Councils information security policy documents in terms of features and components. The content analysis research technique was employed to characterize the information security policies. The profile of the policies is presented and discussed and propositions for future work are suggested.

Keywords: Information Security Policies; Information Security; Content Analysis

1. Introduction

With the advent of information technology (IT) and the massive use of the Internet and its services, the number of threats to which information is subject is increasingly higher and, consequently, the need to protect information systems (IS) is becoming imperious. The coordinated set of efforts to protect information system’s assets is commonly referred to as information security management activity.

In order to protect information, an organization implements a set of measures, also known as security controls, countermeasures, or safeguards, which can take many forms, such as policies, procedures, guidelines, practices, and organizational structures [ISO/IEC 2009].

Given the centrality of ISPs, it is not surprising that the literature contains several contributions that aim to help organizations formulate, implement and review security policies. In addition to recommendations on the process of creating and implementing security policies, the literature includes studies whose authors discuss factors that enable the successful employment of security policies, as well as various guidelines on the content these documents should present.

Despite the significant number of studies on the topic of ISPs, until mid-2000s the literature revealed a limited number of empirical studies on this security measure. Indeed, some authors had pointed to limitations on the research performed, such as the inexistence of a coherent theory about information security policies [Hong et al. 2003] and the inexistence or low expression of empirical studies focusing on the adoption, content and implementation of information security policies [Fulford and Doherty 2003, Knapp et al. 2006]. Since the time when these observations were made, several studies have arisen on ISPs of empirical nature, such as Karyda et al. [2005] and a significant group of studies focusing on employee compliance with ISPs, among which are Boss et al. [2009], Bulgurcu et al. [2010], Herath and Rao [2009], Johnston and Warkentin [2010], Myyry et al. [2009], Siponen and Vance [2010], and Warkentin et al. [2011]. The majority of the works in this last set of studies promoted surveys that addressed the intentions and behaviors of employees, examining factors which facilitate or inhibit compliance with ISPs. These works, however, did not consider the specific ISPs documents held by organizations nor the connection between the wording in those documents and employees’ behaviors or intentions to protect information systems assets.

We argue that IS security literature may be enriched by inquiring on what organizations do in terms of ISPs, the reasons for their choices, the difficulties they face during their formulation and implementation and on how they eventually overcome those difficulties. Armed with empirical data on the use of ISPs by organizations, we may be able to make better recommendations for practice, to check if there is a gap between what the literature advocates and what organizations actually materialize and to reason about the relationship between ISPs documents and user compliance.

This work seeks to contribute to that purpose. Since it is not feasible, nor even conceivable, to address the whole thematic spectrum of ISPs, we decided to focus the work on the content of policies. The aim of the study is to characterize the documents that have been formally adopted by organizations as ISPs, centering the analysis on their content.

The paper is structured as follows. After this introduction, we review the literature on the content of ISPs. Then, the research questions are presented and the research strategy is described. Afterwards, we present the main results of the study and discuss them. The paper ends by drawing conclusions and suggesting future work.

2. Literature Review

A literature review on information security policies enabled the identification of three fundamental classes of meaning attached to this security control.

Condensing these three classes of meaning, in this study we define ISPs as documents that guide or regulate people or systems’ actions in the domain of information security [de Sá-Soares 2005].

Having clarified our understanding of ISP, and given the focus of this study, next we review the literature on information security policies content, organizing the contributions into two groups: features of policies and components of policies.

2.1 Features of Information Security Policies

The features of an ISP are the set of characteristics that the policy document presents. The literature review identified regularities among the works of several researchers with regard to the features an ISP should possess. Among the features that gather more consensus are its short length, accuracy and clarity, ease of understanding, high level of abstraction, durability and independence from the technology and specific security controls [Barman 2001; Hone and Eloff 2002b; Palmer et al. 2001; Peltier 2002; Pipkin 2000].

The length of a policy depends on the amount and complexity of the systems and agents that it covers, as well as the level of abstraction applied in its writing, since a document with a high level of abstraction will not come into extensive detail. Höne and Eloff [2002a] recommend a length ranging between one and five pages.

The way policies are written is another preponderant factor considered in the literature, which reinforces the need for the text to be accurate, clear and easily understood. All these formal features of policies suggest the concern that researchers place on the need of the recipients of these documents to assimilate them quickly, completely, and unambiguously. This concern is demonstrated by Simms [2009], by arguing that policy formulation must produce documents that are clear, simple and focused on the target audience and that they should include definitions of technical terms used in them, to minimize inconsistencies in their interpretation and to prevent that users do not comply with policy determinations due to a lack of understanding of the documents. This need to write policies in plain language and easy to understand had already been highlighted by Kee [2001], who advanced the SMART rule (acronym for Specific, Measurable, Agreeable, Realistic and Time-bound) as a guide for writing these documents.

The durability of policy documents points to the need to revise the wording in the policy at regular intervals. This implies that these documents should have an expected duration, after which they should be subject to assessment in order to determine their adequacy and timeliness. This feature enables that changes in IT or business are taken into account, as well as eventual inadequacies of policies’ provisions to the context for which they were originally conceived. While policies may consist of provisional documents, they should not be found in a continuous review process, since it is expected that these documents show a minimum stability over time. This stability of policies will depend, in part, on not being too dependent upon specific IT, which could happen if they included references or assumptions about the more technical aspects related to the implementation of security mechanisms, as these may vary over time [Hone and Eloff 2002b].

An additional feature of the policies is how they are structured, with different authors recognizing different forms of structuring. Lindup [1995] acknowledges the existence of organizational policies, which establish general guidelines for the information security program, and of technical policies, which establish the security requirements that a product or a computer system should observe. In turn, Whitman et al. [2001] acknowledge the existence of three fundamental structures for policies:

Individual policy—In this structure, the organization creates a separate and independent security policy for each technology and system used.

Complete policy—In this structure, which is the most common according to the authors, the organization centrally defines, controls and manages one single document which includes all the technologies used and provides general guidelines to all the systems used by the organization.

Modular complete policy—This policy is centrally controlled and managed as in the case of the complete policy, and it consists of general sections, with descriptions of the technologies used, and discussions about the systems responsible and appropriate use. It differs from the previous structure because it includes modular appendixes, which provide specific details on each technology and bring forward particular observations, differences, restrictions, and functionalities related to the use of technology which are not properly covered in the base policy document. For Whitman et al. [2001], this is the most effective structure for information security policies.

The medium in which the policy takes shape should be considered. It may be available printed or in electronic format, in which case it may be easier to change and disseminate by its recipients.

Finally, one may ask what kind of documents the policies are. The consideration of the policies’ titles and the analysis of their components may help typifying the documents.

2.2 Components of Information Security Policies

The components of an information security policy are the set of elements that the policy document contains, i.e., its constituent parts.

The attempt to generalize the elements that an ISP should include is hampered by the dependence that the composition of these documents presents on the nature of the organization, its size and goals [Dhillon 1999; Karyda et al. 2003]. Although it is accepted that an ISP may vary considerably from organization to organization, this possibility has not prevented some authors from moving forward with guidance on the elements that policies should typically include. Thus, Wood [1995] claims that ISPs should include general statements of aims, goals, beliefs and responsibilities, frequently accompanied by general procedures for their achievement.

Whitman [2004] argues that a good ISP should outline individual responsibilities, define which users are allowed to use the system, provide employees with an incident reporting mechanism, establish penalties for violations of the policy, and provide a policy updating mechanism.

Given the importance of currently available normative references for the information security management activity, the ISO/IEC 27000 series of standards should be taken into account, namely ISO/IEC 27002, with respect to the components of an ISP. According to this international standard, the policy document should establish the management commitment to information security and contain the following statements [ISO/IEC 2005]:

A definition of information security, its overall objectives, scope and the importance of security as an enabling mechanism for information sharing

A statement of management intent, supporting the goals and principles of information security aligned with the business strategy and objectives

A framework for setting control objectives and controls

A brief explanation of the security policies, principles, standards, and compliance requirements of particular importance to the organization (compliance with legislative, regulatory, and contractual requirements; security education, training, and awareness requirements; business continuity management; and consequences of information security policy violations)

A definition of general and specific responsibilities for information security management

References to documents which may support the policy, such as more detailed security policies and procedures for specific information systems or security rules users should comply with.

By comparing several information security standards, Hone and Eloff [2002a] isolated the following elements as generic components that ISPs should include:

Need for and Scope of Information Security

Objectives of Information Security

Definition of Information Security

Management Commitment to Information Security

Approval of the Information Security Policy

Purpose or Objective of the Information Security Policy

Information Security Principles (risk management, compliance, access control, etc.)

Roles and Responsibilities

Information Security Policy Violations and Disciplinary Actions

Monitoring and Review

User Declaration and Acknowledgement

Cross References (to other information security documents)

General Elements (authors, date of policy and review date of policy)

Among the studies reviewed, the components that collect more consensus are the purpose of the policy, its scope and the responsibilities it assigns to organizational agents. The purpose sets out the main objectives of the policy and the reasons that led to its formulation [Robiette 2001]. The scope identifies the systems to which the policy applies, the employees to whom it is addressed and the situations in which it is relevant [Hare 2004]. The responsibilities clarify the duties of managers, technicians and other employees with regard to information security [Kovacich 1998].

3. Research Questions

The aim of the study is to characterize the content of ISP documents that have been adopted by organizations. Its motivation was the intention to supplement accumulated knowledge with work grounded in the analysis of information security empirical materials.

Bearing in mind the goal of the work and how the literature review on the content of ISPs was organized, we seek to answer the following research question: What features and components do information security policy documents present in practice?

Linking this question with the main contributions of the literature allowed us to instantiate the specific questions that guided the analysis in terms of policies’ features and components. Thus, with respect to the features of policies, we will address the following issues:

What is the length of the policy documents?

How are the policies written?

What is the expected durability of the policy documents?

What is the structure of the policies?

In what medium are the policies delivered?

What kind of documents are the policies?

In what regards the policies’ components, we put forward the following specific questions:

What components do the policies contain?

Are there components that form part of all policy documents?

Are there components that are not present in any of the policy documents?

What is the purpose of the policies?

What is the scope of the policies?

What kinds of responsibilities do the policies determine?

The analysis of the provisions contained in the policies may also allow understanding of whether the adopted policies configure documents of a more descriptive or of a more prescriptive nature. Specifically, the analysis of the responsibilities component may clarify whether the policy documents, in practice, regulate behavior through the establishment of prohibitions or permissions.

The answer to these questions will enable to relate the features and components of the policies reviewed with the recommendations made in the literature with regard to the content that policy documents should display. This comparison will allow the assessment of the extent to which the documents adopted by organizations reflect the recommendations of the literature and, eventually, the identification of any discrepancies whose understanding may require further inquiry.

4. Research Strategy

Since this study aims to analyze ISP documents actually adopted by organizations, the first challenge to the design of this research was to obtain those documents. Given the intention of making a comparison between several policy documents, it was decided to restrict the collection of documents to a single organizational sector. With this option, we sought to minimize the possibility of documents belonging to different sectors having different features and components, due to particular characteristics of each of those sectors as well as specific information security needs.

The sector selected for the collection of policies was the local government in Portugal. This sector was selected for two major reasons. First, being one of the main investors in IT [Gartner 2009], the government sector offers an interesting case for studying information security, and among the various Public Administration institutional agents, City Councils assume a specific relevance, as they concentrate a growing demand from their citizens for quality information services and for the diversity and quantity of data they deal with in the performance of their duties. Considering the information they manipulate, the security of their IS is indispensable to their normal functioning and to the protection of personal data which they are entrusted with. The second reason relates to previous research undertaken by the authors on local government information security. Having conducted a survey on ISPs adoption, we found that 38 (12%) of the 308 Portuguese City Councils said to have adopted ISPs and 270 (88%) have not adopted any policy yet [Lopes and de Sá-Soares 2010].

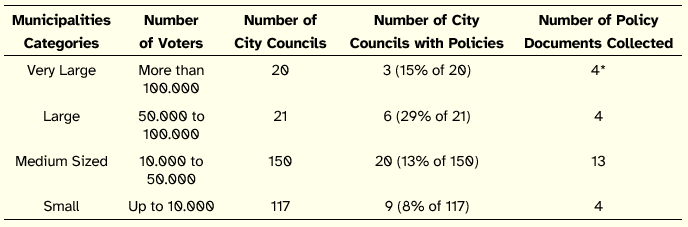

For the present study, we contacted those 38 City Councils and asked them to provide us the ISP document. This interaction resulted in the collection of 25 documents, which are the basis for this study. The distribution of the documents collected is presented in Table 1 (the figure marked with an asterisk is explained by the fact that one City Council had formulated an ISP, but was awaiting formal approval for its adoption at the time the research team asked the policy documents to City Councils).

Table 1: Distribution of Policy Documents Collected

The process of content analysis starts with the creation of a scheme of categories composed of the various analysis units. The more clearly formulated and well adapted to the problem and content under analysis the categories are, the more productive the studies using content analysis will be [Berelson 1952]. After the system of categories to use in the analysis has been established, it is possible to move on to the coding stage.

From a procedural point of view, the analysis of ISPs proceeded as follows:

Elaboration of the codebook—The second author elaborated a codebook to support the analysis of the documents. The codebook development followed the general guidelines provided by MacQueen et al. [1998]. The codes were defined based on an extensive review of the literature on ISPs and of nine standards in the field of information security. Besides the code identifier, each code has associated the following fields of information: code name, brief description, full description, when to use the code, and when not to use the code. The codebook is composed of 51 main codes. Some of these codes require the juxtaposition of subcodes, namely the targets of the policy as specified in its scope, specific responsibilities of the policy owner, entities to contact for specific purposes related to the policy, to whom a policy provision applies, the type of particular responsibilities and the information security object a particular provision of the policy refers to.

Elaboration of coding instructions—The second author prepared a document with instructions to guide the coding stage. These instructions include preparatory work to undertake before starting coding and the sequence of steps that should be performed by the coder when processing each policy document, including what to do if questions arise during the coding process.

Set up of coding team—A team of two coders was set up for analyzing the policies. One of the coders was the first author of this paper and the other coder was a third researcher. Both researchers were versed on information security.

Preparation of the coding team—The coding team performed several preliminary tasks before starting the coding process of the 25 policies. After a thorough study of the codebook and coding instructions, a meeting was set up with coders and the author of the codebook and coding instructions to answer questions that the study might have raised. Since the coding process can be made easier and more systematic by using text processing tools, in this study the coders resorted to the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti. Assisted by this program, the coders were trained using the codebook and coding instructions by coding four ISPs not pertaining to the 25 policies that form the basis of this study. A second meeting was held with the author of the codebook and coding instructions to jointly analyze the quality of the coding and to clarify any pending issues. Whenever the phrasing used in the codebook was considered ambiguous, the second author clarified it, producing a revised version of the codebook.

Preparation of the documents—The first author prepared the documents to comply with the coding instructions and to allow the use of qualitative data analysis software.

Coding process—Each coder individually coded the 25 ISPs. At the end of this process, the coders met to discuss specific dissimilarities in the output of the coding process and to make fine adjustments to some units of analysis in what concerns the degree of coding detail.

The time spent on coding by the two coders was approximately 120 hours, which corresponds to an average of 2.4 hours per policy document per coder.

5. Results

The length of the ISP documents analyzed ranges between a maximum of 26 pages and a minimum of one page. The average length is 8.8 pages, with standard deviation of 6.2 pages. For a 99% confidence interval, the population mean is in the range defined by 9 ± 2 pages. In terms of words, the documents range between a maximum of 5497 words and a minimum of 125 words, with an average length of 2180 words and standard deviation of 1468 words. For a similar confidence interval, the population mean is in the range defined by 2180 ± 485 words.

In the opinion of the coders, most of the policy documents are easy to read and to understand, properly structured and written in a clear, correct and intelligible language. Some of the documents that apply technical terms in the realm of information security provide a list of definitions for those terms.

The majority of the documents do not allow any inference in what regards its durability. Of the 25 documents, only one policy displays its default expected durability, by stating when the document should be reviewed.

All of the policy documents were provided in electronic version, except one that was sent printed by conventional mail. The examination of the policies showed that in five documents (20%), the policy determined what medium should be employed for its dissemination: three by electronic means (intranet and email) and two printed.

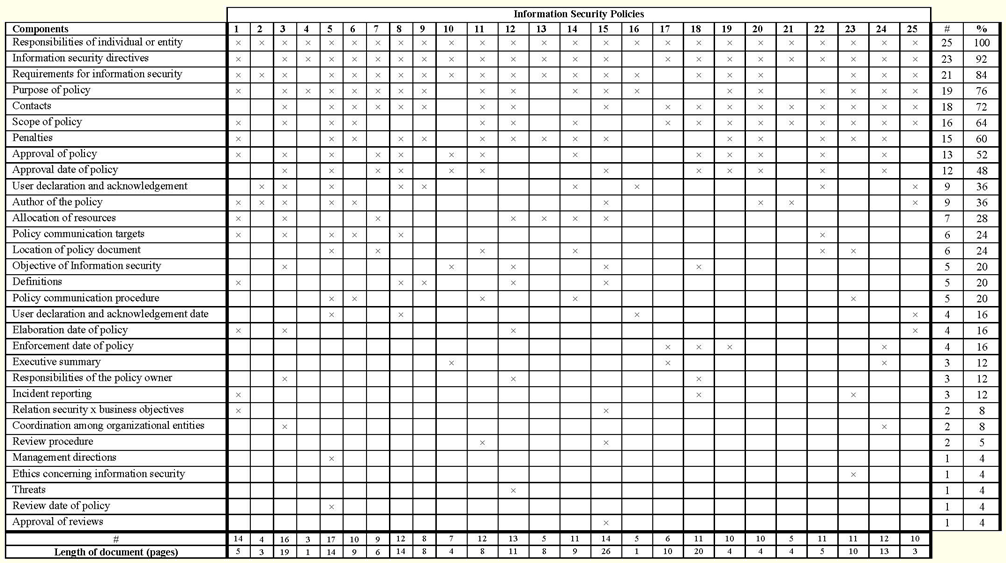

With regard to the components comprised in the policies, there is considerable variation among the documents analyzed. Although several potential components were taken into account in this study, in Table 2 we present the most frequent components that were found in the policies. The list was sorted in descending order of frequency.

Table 2: Components Contained in the Information Security Policies

In some documents, the purpose of the policy was stated as the reason for why the policy was formulated and in other documents to specify what the City Council wants to achieve with the policy. The incidences of the purpose are the IT resources (eight cases), internet and email (five cases), information (five cases), acceptable use of IT (three cases), and IT/IS resources optimization (two cases). Some of the documents specify purposes that fall in more than one of the previous categories.

Of the 13 documents where the scope of the policy is specified, nine apply to individual organizational collaborators, seven to IT systems and three to organizational units (the sum is greater than 13 because six documents include more than one scope target). None of the documents identifies information on its scope specification.

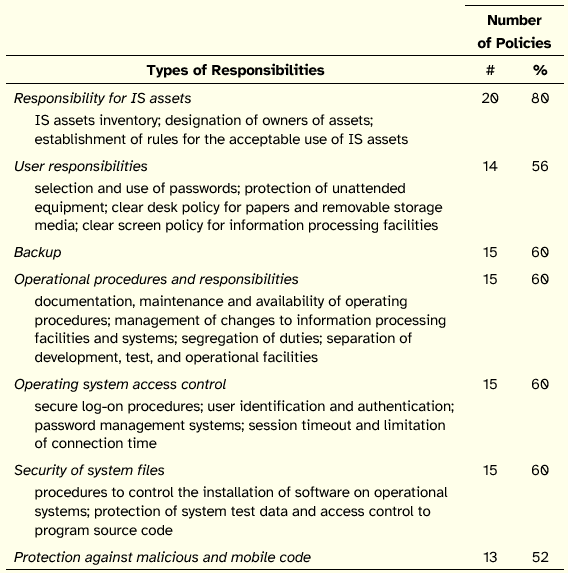

In what concerns responsibilities, the major types of responsibilities allocated to users or organizational units, i.e., those that appear in more than half of the documents, are listed in Table 3, alongside with the absolute and percent number of documents mentioning the type in question.

Table 3: Major Types of Responsibilities

It should be stressed that the recommendations contained in the information security policies vary according to the type of user they refer to. There are provisions, such as operational procedures and responsibilities, whose targets are IT/IS technicians. The responsibility for maintaining, monitoring compliance, and reviewing the information security policy usually rests on a specific IT/IS unit (the IT/IS unit). Considering generic users (all those that manipulate information in the organization and that use IT equipment), the analysis of the documents revealed there are a set of responsibilities that can be said to be transversal to most of the documents, namely those regulating the use of email, internet use, IT equipment use, software protected by copyright and internal computer network use.

6. Discussion

The average length of the policies exceeds what is recommended by some authors as being the ideal length. Two documents are very brief (one page long), merely setting rules for internet and email use. Nine policies are lengthy (more than nine pages long) and include detailed provisions for a wide range of IT/IS and address different audiences (generic users, IT/IS technicians, organizational units). Typically, these documents consist of internal regulations, organized into chapters and articles. In these documents information security related provisions go along with other types of determinations, such as the IT/IS unit’s organization, competencies and responsibilities and the role IT plays in the organization. Therefore, several of the documents analyzed do not confine to ISPs, including other provisions associated to IT/IS, besides those related to information security.

The analysis revealed that the main recipients of the documents are generic users of IT/IS and IT/IS technicians. Given the heterogeneity of generic users covered by the policies, the language used in the documents is clear and easy to read. Most of the longer documents target the two types of recipients. The coexistence of these two types of recipients in the same document may decrease its effectiveness since it puts together audiences with different responsibilities, knowledge, skills, and requirements in the context of IS security. Keeping apart generic users from IT/IS specialized users, by developing two separate documents, could increase the effectiveness of policies. Alternatively, City Councils could choose to structure their ISP documents as modular policies, where a root and general document is supplemented by modular appendixes which may be suited to different targets and situations.

The type of the policy document appears to depend on the type and diversity of its recipients: whenever there is a wider access to IT/IS, this access is controlled by regulation, which will have to be approved by the Municipal Assembly in order to be effective by law; whenever the IT/IS are accessed only by and for the City Council employees, the control is established by norms, job instructions, policies, or rules. Whatever the case, the titles of the documents are aligned with the specific praxis and universe of discourse of public administration agencies.

Most of the documents analyzed are fundamentally IT/IS acceptable use policies, focusing on the daily work routine of employees in what concerns the manipulation of information and IT. The priorities of this acceptable use are concentrated on the compliance with legal requirements (e.g., respect for copyrights, using IT resources only for business related activities and not participating in abusive or illicit use of IT/IS), secure information exchange (e.g., not opening suspicious email attachments, not downloading software from the internet and maintaining the antivirus application updated), definition of responsibilities for IS assets, and management of users’ access to IT/IS. It is also expected that the responsible use of IT/IS will lead to an optimization of IS/IT resources, including freeing the IT/IS unit from time consuming tasks resulting from user misuse of systems and applications.

The option for printed documents seems to be justified by the need for users to sign a term of acknowledgement and responsibility concerning information security provisions.

With regard to the components found in the ISPs, there is an oscillation in variety and frequency (cf. Table 2). Behind this finding may be the fact that City Councils differ in terms of information security management maturity levels. The intensity and complexity of their use of IT/IS may also play an important role in the degree of sophistication of their security policies. Whatever the case, the City Councils that have a complete ISP document in the light of the literature are few in number. This may result from a lack of clear and coherent ISP models which can be adopted by City Councils according to their own security needs (to date in Portugal there was no generic ISP document issued by a central governmental agency that City Councils had to adopt). Exploring the association between the length of policies and the number of components present, one finds Pearson r = 0.64 (for the length in pages) and r = 0.63 (for the length in words—calculating the association between the natural logarithm of the number of words and the number of components increases r to 0.68), both values for p < 0.001. The corresponding coefficient of determination amounts to 40%, suggesting that an increase in the length of policy is associated with an increase in the components present in the ISP document. To some extent this could be expected—longer documents may just contain more elements, but it raises questions regarding the size of ISP documents that is actually needed to accommodate the number of policy components suggested in the literature.

In only one case there is a reference to the time scope in which the policy should be revised. This may result in a potential gap between the policies’ provisions and the risks that continuously appear along with the technological and business evolution. Other components, though not totally absent, are only found on a subset of the documents, such as who approved the policy document (when present, the approval is mainly obtained in the Council meeting), how security objectives serve business objectives, and the mechanism to report information security incidents.

Bearing in mind the number of prohibitions and obligations that stand out in the policies, the documents show a clear tendency to a more imposing or imperative character of behavior adoption or abstention concerning IT/IS users and technicians. Although the policies reveal a high degree of behavior and conduct imposition or prescription, thus having an undeniably prescriptive character, if one considers the high level of detail enclosed in several policies, these documents also assume a descriptive character. The descriptive parts of the documents educate and inform readers on issues such as the importance of IT to City Councils’ missions, responsible use of IT, internal organization of the IT/IS unit, applicable legal requirements, and general security directives.

7. Conslusion

This study involved the characterization of 25 information security policies adopted by Portuguese City Councils in terms of components and features. This work contributes to the literature by analyzing information security empirical materials and bringing more practical and practitioner oriented perspectives to information security research. By focusing on the substance and form of actual ISPs, it elucidates an area of information security research that has been largely ignored, in spite of its practical relevance for the improvement of information security by organizations and supplements the literature whose traditional focus has been on individual intentions towards ISPs. Besides comparing the recommendations in literature concerning ISPs content with the practice performed by organizations, the paper laid groundwork for assessing the connection between ISP content and ISP compliance. The work also resorted to a less-utilized method in information security research, evidencing that content analysis is a well suited approach to examine ISP documents.

This research work has some limitations, namely with regard to the number of documents collected. Although we believe that the 25 policies generated enough data to serve the purpose of the work, we also believe that a larger number might result in a richer and more sustained data set. Nevertheless, it should be noted that information security policies are generally considered reserved documents by organizations, which makes hard the access to this kind of security control.

Another limitation of this paper regards the delimitation of the study to one organizational sector and to the national territory. This prevents conclusions concerning differences related to the missions as well as the functioning of other types of organizations as well as possible cultural differences regarding City Councils or other organizations in other countries or cultures.

Among the possible works to be carried out in the future, we point out the proposal of an ISP template, so that it may be used as a potential model in an attempt to invert the reduced number of existing policies in the Portuguese City Councils.

Another future work stemming from one of the limitations is to analyze ISP documents of organizations belonging to other sectors. This would enable the comparison of policy documents’ content in terms of features and components, for instance between public sector organizations and private organizations.

Lastly, it would make sense to promote research focusing on the process of adopting ISPs by City Councils, namely in what relates to the formulation and implementation of policies. By studying how organizations develop their ISPs we may find out the reasons for these documents to present the features and components discussed in this paper. Similarly, by interviewing these organizations about ISP implementation we could be in a better position to relate ISP contents to ISP compliance by users, thus contributing to bridge the gap between information security theory and practice.

References

ACL (2001). Dicionário de Língua Portuguesa Contemporânea da Academia das Ciências de Lisboa. Lisboa: Verbo.

Babbie, E. (1999). Métodos de Pesquisa de Survey. Belo Horizonte: UFMG.

Barman, S. (2001). Writing Information Security Policies. Indianapolis: New Riders.

Baskerville, R. and M. Siponen (2002). An information security meta-policy for emergent organizations. Logistics Information Management 15 (5/6), 337–346.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content Analysis in Communications Research. New York: Free Press.

Bosch, C., J. Eloff and J. Carroll (1993). International Standards and Organizational Security Needs: Bridging the Gap. Proceedings of the IFIP TC11 Ninth International Conference on Information Security, 171–183

Boss, S. R., L. J. Kirsch, I. Angermeier, R. A. Shingler and R. W. Boss (2009). If someone is watching, I’ll do what I’m asked: mandatoriness, control, and information security. European Journal of Information Systems 18(2), 151–164.

Bulgurcu, B., H. Cavusoglu and I. Benbasat (2010). Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical Study of Rationality-Based Beliefs and Information Security Awareness. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 523–548.

Dhillon, G. (1999). Managing and controlling computer misuse. Information Management & Computer Security 7(4), 171–175.

Fulford, H. and N. F. Doherty (2003). The application of information security policies in large UK-based organizations: an exploratory investigation. Information Management & Computer Security 11(3), 106–114.

Gartner (2009). Dataquest Alert: Forecast, IT Spending in Industries, Worldwide, 3Q09 Update. October.

Gilbert, C. (2003). Guidelines for an Information Sharing Policy. SANS Institute.

Guel, M. (2007). A Short Primer for Developing Security Policies. SANS Institute.

Hare, C. (2004). Policy Development. In Tripton, H. F. and M. Krause (Eds.), Information Security Management Handbook, fifth edition. 925–944. Boca Raton: Auerbach.

Herath, T. and H. R. Rao (2009). Protection motivation and deterrence: a framework for security policy compliance in organisations. European Journal of Information Systems 18(2), 106-125.

Higgins, H. N. (1999). Corporate system security: towards an integrated management approach. Information Management & Computer Security 7(5), 217–222.

Höne, K. and J. Eloff (2002a). Information security policy—what do international information security standards say? Computers & Security 21(5), 402–409.

Höne, K. and J. Eloff (2002b). What makes an effective security policy? Network Security 6(1), 14–16.

Hong, K. S., Y. P. Chi, L. R. Chao and J.-H. Tang (2003). An integrated system theory of information security management. Information Management & Computer Security 11(5), 243–248.

ISO/IEC (2005). ISO/IEC 27002—Information technology—Security techniques—Information security management systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

ISO/IEC (2009). ISO/IEC 27000—Information technology—Security techniques—Information security management systems—Overview and vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization/International Electrotechnical Commission.

Johnston, A. C. and M. Warkentin (2010). Fear Appeals and Information Security Behaviors: An Empirical Study. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 549–566.

Karyda, M., S. Kokolakis and E. Kiountouzis (2003). Content, Context, Process Analysis of IS Security Policy Formation. In Gritzalis, D., S. D. C di Vimercati, P. Samarati and S. K. Katsikas (Eds.), Security and Privacy in the Age of Uncertainty, 145–156. IFIP TC11 International Conference on Information Security (SEC2003), IFIP Conference Proceedings. Amsterdam: Kluwer.

Karyda, M., E. Kiountouzis and S. Kokolakis (2005). Information systems security policies: a contextual perspective. Computers & Security 24(3), 246–260.

Kee, C. (2001). Security Policy Roadmap—Process for Creating Security Policies. SANS Institute.

King, C. M., C. E. Dalton and T. E. Osmanoglu (2001). Security Architecture: Design, Deployment, and Operations. Berkeley: Osborne/McGraw-Hill.

Knapp, K., R. Marshall, K. Rainer and N. Ford. (2006). Information Security: Management’s Effect on Culture and Policy. Information Management & Computer Security 11(1), 24–36.

Kovacich, G. L. (1998). The Information Systems Security Officer’s Guide: Establishing and Managing an Information Protection Program. Woburn: Butterworth-Heineman.

Lindup, K. R. (1995). A New Model for Information Security Policies. Computers & Security 14(8), 691–695.

Lopes, I. and F. de Sá-Soares (2010). Information Systems Security Policies: A Survey in Portuguese Public Administration. Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference on Information Systems, 61–69. Porto.

MacQueen, K. M., E. McLellan, K. Kay and B. Milstein (1998). Codebook Development for Team-Based Qualitative Analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods 10(2), 31–36.

Myyry, L., M. Siponen, S. Pahnila, T. Vartainen and A. Vance (2009). What levels of moral reasoning and values explain adherence to information security rules? An empirical study. European Journal of Information Systems 18(2), 126–139.

Palmer, M. E., C. Robinson, J. C. Patilla and E. P. Moser (2001). Information Security Policy Framework: Best Practices for Security Policy in the E-commerce Age. Information Systems Security 10(2), 13–27.

Peltier, T. R. (2002). Information Security Policies, Procedures, and Standards: Guidelines for Effective Information Security Management. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications.

Pfleeger, C. P. (1997). Security in Computing, second edition. London: Prentice-Hall International.

Pipkin, D. L. (2000). Information Security: Protecting the Global Enterprise. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall PTR.

Robiette, A. (2001). Developing an Information Security Policy. JISC, http://www.jisc.ac.uk/aboutus/howjiscworks/committees/subcommittees/pastcommittees/jcas/jcaspaperssecurity.aspx

de Sá-Soares, F. (2005). Interpretação da Segurança de Sistemas de Informação segundo a Teoria da Acção. PhD Thesis, University of Minho, Guimarães.

Schneier, B. (2000). Secrets and Lies: Digital Security in a Networked World. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Shorten, B. (2004). Information Security Policies from the Ground Up. In Tripton, H.F. and M. Krause (Eds.), Information Security Management Handbook, fifth edition, 917–924. Boca Raton: Auerbach.

Simms, D.J. (2009). Information Security Optimization: From Theory to Practice. ARES–International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, p. 675-680.

Siponen, M. and A. Vance (2010). Neutralization: New Insights into the Problem of Employee Information Systems Security Policy Violations. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 487–502.

Warkentin, M., A. C. Johnston and J. Shropshire (2011). The influence of the informal social learning environment on information privacy policy compliance efficacy and intention. European Journal of Information Systems 20(3), 267–284.

Weber, R. (1990). Basic Content Analysis, second edition. Sage University Paper.

Whitman, M. E. (2004). In Defense of the Realm: Understanding Threats to Information Security. Informational Journal of Information Management 24(1), 3–4.

Whitman, M. E., A. M. Townsend and R. J. Aalberts. (2001). Information Systems Security and the Need for Policy. In Dhillon, G. (Ed.), Information Security Management: Global Challenges in the New Millennium. Idea Group Publishing.

Wood, C. C. (1995). Writing InfoSec Policies. Computers & Security 14(8), 667–674.