Original source publication: Fernandes, I. X., F. de Sá-Soares and A. Tereso (2022). Modelling and Analyzing Product Development Processes in the Textile and Clothing Industry. Proceedings of the International Conference Innovation in Engineering—ICIE 2022, Guimarães (Portugal).

The final publication is available here.

Modelling and Analysing Product Development Processes in the Textile and Clothing Industry

a Master’s in Industrial Engineering, University of Minho, Campus de Azurém, Guimarães, Portugal

b Centre ALGORITMI, Department of Information Systems, University of Minho, Campus de Azurém, Guimarães, Portugal

c Centre ALGORITMI, Department of Production and Systems, University of Minho, Campus de Azurém, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

The textile and clothing industry is one of the most important sectors in the Portuguese economy, operating in a market that is increasingly competitive, globalized and characterized by short lifecycles and consumer volatility. This leads to an increased need for agility and speed by manufacturers, in order to respond to the market demands. Thus, it becomes important to companies in the sector to understand and diagnose its product development processes in order to identify opportunities for improvement, potentially changing the organisation conventional routines. This work adopted a case study research strategy to critically analyse and discuss the product development process of a major player in the fashion retail sector. For that goal, processes were mapped using business process modelling tools such as Business Process Model and Notation, highlighting the problems and opportunities in the development of new products in the textile and clothing industry, and providing context for the consideration of new measures to enhance its efficiency.

Keywords: Process Modelling; Product Development; Textile and Fashion Industry

1. Introduction

Headed to exportation, the Textile and Clothing Industry (TCI) remains as one of the most important Portuguese industrial sectors [CITEVE 2012]. After a period of decline, boosted by the global economic crisis, the sector has been recovering, currently representing 10% of total national exports and 8% of volume of business with 19% of the employability of the manufacturing industry [ATP 2019]. This is an industrial sector characterized by a high commitment to innovation, design and quality, in order to face a global and increasingly competitive market [Cardoso and Quelhas 2018]. The fashion retail sector is characterized by very short life cycles, instability in consumer preferences and a high heterogeneity of supply, leading to increased competitiveness in the market. Therefore, this sector presents a volatile and risky market, with product life cycles planned to be short, in order to capture consumer interest [Dapiran 1992]. Fashion apparel producers face the need to permanently deliver new products to fulfil the orders requested by retailers, boosted by consumer market trends. Due to the reduced life cycle of these products, their development must be fast and efficient, in order to develop a competitive advantage in the market. Characterized by the need for agility, the process of developing new products in the fashion clothing sector requires the adoption of practices that enhance efficiency. To pursue that excellence, the process of clothing development needs to be carefully understood and diagnosed, in order to find out opportunities for its improvement.

We argue that Business Process Management is a valuable tool for the modelling the Product Development Process (PDP) in the sector, assisting in the understanding of how the development of new products in the TCI is processed, and providing a basis for the projection of new measures that enhance its efficiency.

sThis paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review, addressing relevant topics, namely Product Development and Business Process Management; Section 3 describes the research methodology followed; Section 4 explores the results of the study; finally, Section 5 concludes the paper, underlining some limitations and presenting relevant future research.

2. Literature review

2.1 Product Development

The reference to a new product happens when a product or concept is totally new to the market, or totally new to the company, despite the existence of similar products on the market [Panwar and Bapat 2007]. In an increasingly competitive market, the development of new or improved products and services is crucial for the survival and prosperity of organizations [Kahn et al. 2013]. Product development is increasingly considered a critical business process for the competitiveness of companies, especially with the growing internationalization of the market, increasing diversity and variety and reducing the life cycle of products [Rosenfeld et al. 2006].

The design of a product is the process that takes place at the beginning of its life cycle, which includes moments of research, experimental development, and marketing [OECD and EUROSTAT 2005]. Therefore, it consists in the sequence of steps or activities that an organization takes to conceive, design and market the product [Ulrich and Eppinger 2016], in order to convert needs into technical and commercial solutions [Smith and Morrow 1999]. Product development activities start with the perception of a market opportunity and end with the production, sale, and distribution of a product. The precise and detailed definition of a PDP is useful and important because it [Ulrich and Eppinger 2016]:

Ensures higher quality of the process;

Stimulates coordination between the elements involved in the process;

Keeps the process planning updated;

Allows managing process performance; and

Promotes continuous improvement of the organization’s PDP.

Product development in clothing and fast-fashion

The PDP is a divergent process, which varies depending on the context of the organization. Since this work is based on the TCI, and more specifically on the production of clothing for the fast-fashion market, it is important to know the characteristics of this market in order to understand its specific needs and the particularities of its product development process.

In the last 20 years, the textile and clothing industry has evolved significantly. Mass production began to disappear and products with a shorter life cycle appeared and the number of collections increased, forcing manufacturers to change their supply chain in order to be able to produce at a lower cost and with greater flexibility, quality and speed to market [Bhardwaj and Fairhurst 2010]. In part, this explains the instable nature of the clothing industry, due to the seasonality and subjectivity of the factors that lead to the purchase of products. Thus, to keep up with the complexity of the fashion apparel product, manufacturers need to understand and adopt the most efficient methods, in order to create and produce differentiated models in the shortest possible time [Parker-Strak et al. 2020]. The fast-fashion concept emerged to follow the trend of changing the paradigm of this sector, representing a market that is difficult to predict, with a high buying impulse, shorter life cycles and high volatility in demand [Bhardwaj and Fairhurst 2010]. This concept means that organizations must be able to react to new fashion trends in periods as short as 15 days to 1 month, in order to allow them to remain competitive in the market [Tran et al. 2011], unlike the traditional cycles, in which two annual collections were presented according to the seasons, increasing the number of cycles per year from 2 to approximately 50 [WRI 2021]. Given these characteristics of the market, the product development process has to respond accordingly. Senanayake [Senanayake 2015] identifies the main differentiating characteristics of the fast-fashion clothing PDP as being:

Pull strategy, given that the products developed will be products based on what the market is looking for and asking for at the moment, instead of push production in which the manufacturer introduces products to the market based on history.

Design and development of small productions of multiple styles in short cycles, in order to respond to the market, providing a variety of options in smaller quantities to increase purchase motivation and increase sales.

Speed in design approval, in order to fulfil an efficient validation process and reduce the waiting time until delivery to the customer.

Prefabricated raw material, to guarantee a flexible flow of material for the development of the part.

Close relationship between the elements of the supply chain, since they will be elements that will work closely to develop the product and it is necessary that they are integrated and aligned, so that quickly, and in collaboration, they can respond to the dynamics of the market.

Multidisciplinary in the development teams, since it is a process that goes through several stages, intervening in different areas of action, and thus will require the integration of several elements, with experience in different themes.

Thus, the PDP in the textile and clothing sector, particularly with production for fast-fashion, will have to follow the complexity of the product, creating and producing differentiated models, in a short period of time, while following the trends of the fashion market [Moretti and Braghini Junior 2017].

2.2 Business Process Management

Originating from the Latin processus, process represents a set of interrelated activities and tasks, which are initiated in response to an event, and which aim to achieve a specific result for the process consumer [von Rosing et al. 2014]. A business process is distinguished from other processes since, as its name implies, it is a process applied in a business. Hence, a business process is defined as a set of activities, logical and sequential, that allow the transformation of inputs into outputs, in order to deliver value to the customer [Harrington et al. 1997]. Business processes are coordinated activities that create a final product or service, with inputs and outputs, as well as a defined beginning and end [von Rosing et al. 2014].

In a business, it is possible to classify its processes in three different ways [ABPMP 2013]: primary processes (essential processes of the organization, responsible for adding value to the customer); support processes (support the organization’s primary processes); and management processes (with the objective of measuring, analysing, monitoring, and coordinating all processes of an organization). Each one with its objective, all the processes of the organization are necessary for its proper functioning, and therefore its management is necessary, and hence the need for Business Process Management (BPM). Despite the different definitions of BPM, it is possible to reconcile them as the discipline that involves any combination of modelling, automation, execution, control, measurement, and optimization of an organization’s process flow [von Rosing et al. 2014]. As a result, there is a set of methods, techniques and tools for the design, interaction, control, and operational analysis of business processes, involving people, organizations, applications, documents, and other sources of information.

To represent business processes, visual tools are commonly used which consist of diagrams representing the process, namely, Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN), that allows to illustrate, document, and shape the way an organization develops its business across all its levels, i.e. at the strategic, tactical and operational level [von Rosing et al. 2014].

Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN)

BPMN was introduced in 2004 as a standard language for business process modelling. It is a visual representation that serves to model and represent the operational flows of an organization [vom Brocke and Rosemann 2014]. This tool has the main objective of providing a notation that is understandable by any user of the process, being simple to use and allowing to create flow diagrams that are independent of the type of business they represent [OMG 2013].

The BPMN language is grouped into four major categories of elements [vom Brocke and Rosemann 2014]:

Flow objects

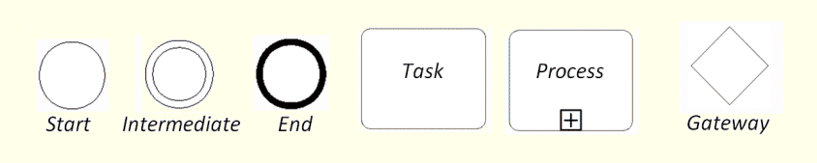

These elements allow to build the business processes, and include the activities (squares), events (circles) and gateways (rhombus), as shown in Figure 1 [Ciaramella et al. 2009]:

Figure 1: Flow Objects at BPMN

Activities—Work units to be carried out during the business process. Among the activities we can have processes, subprocesses and tasks. An activity is a discrete action with a well-defined beginning and end, that is, a function that is performed continuously is not an activity in the BPMN context. Among tasks, one may find several types, depending on their purpose, and they can be distinguished by the use of icons in the upper left corner of the activity element.

Events

—Something that occurs in the process and how the process responds to this event (in the case of being a “ “ Gateways—Decisions in a process, being used to demonstrate the convergence or divergence of the flow of control between activities, events, among others. They are graphically represented by a rhombus and again, depending on their type, take different graphical representations.

Connection objects

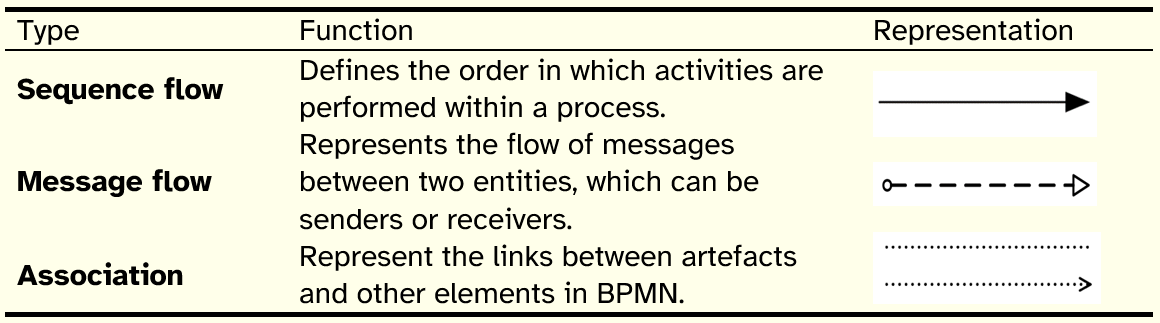

Elements used to connect the flow objects and represent the relationships between them. There are three types of connection objects, depending on their function [OMG 2013] (Table 1).

Table 1: Types of Connection Objects

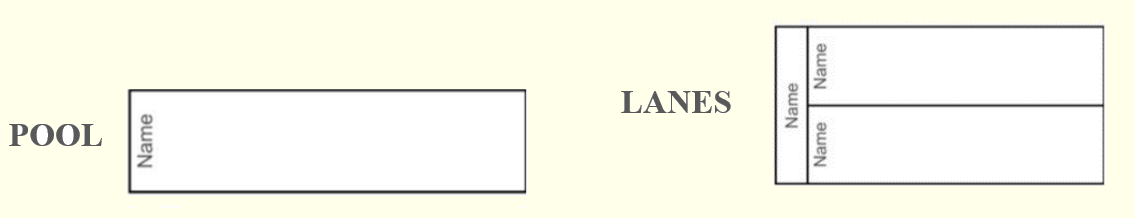

Swimlanes

Elements used to denote a participant in a process and group all the activities carried out by that same participant. Subdividing the pool into lanes allows the activities to be organized and categorized by each entity that performs them (Figure 2). The concepts pool and lane, serve exactly, as their names indicate, to replicate the operation of a pool, in which each swimmer stays in his lane, just like each process contained in its element.

Figure 2: Pool and Lanes in BPMN

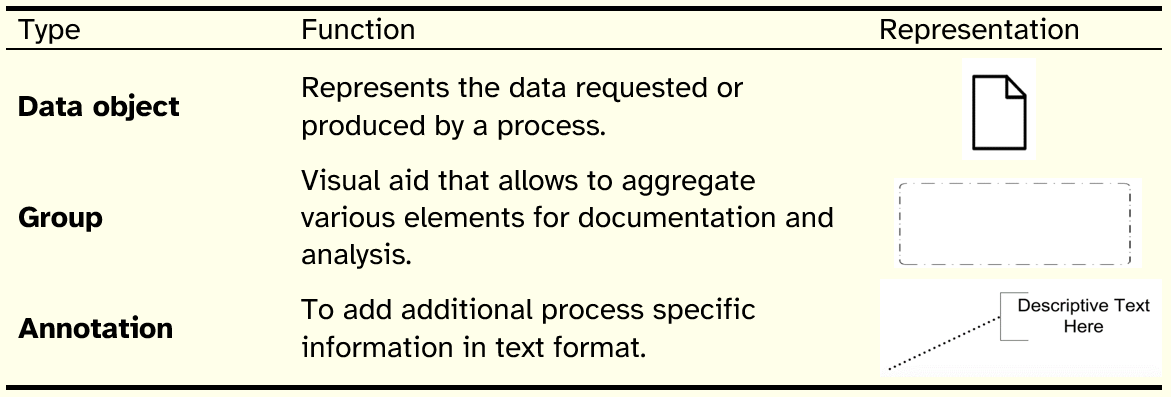

Artefacts

Elements with the purpose of providing complementary information about the represented process. They can be data objects, groups or annotations and each one has a specific purpose, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Types of Artefacts in BPMN

3. Research Methodology

In this context, the case study strategy was applied in a group of companies that stands out in the TCI sector as one of the largest Portuguese textile groups. This group is one of the few complete vertical units worldwide, controlling its production from spinning to confection, and following the entire transformation process of the raw material, from the cotton wool to the finished garment. It is one of the largest suppliers of the Inditex Group worldwide, and therefore its production needs to fit the requirements of the fast-fashion market, with speed and agility being the watchwords in its operation.

To support the findings in this case study, the technique of participant observation was employed. Participant observation is based on collecting data from the point of view of user and researcher active in the work. This technique made it possible to monitor the processes of key users. To enhance the relevance of the data collected, users were selected, taking into account their role in the processes under study. This selection was made together with the company’s production director, based on her extensive knowledge of the process.

4. Results

4.1 Resources

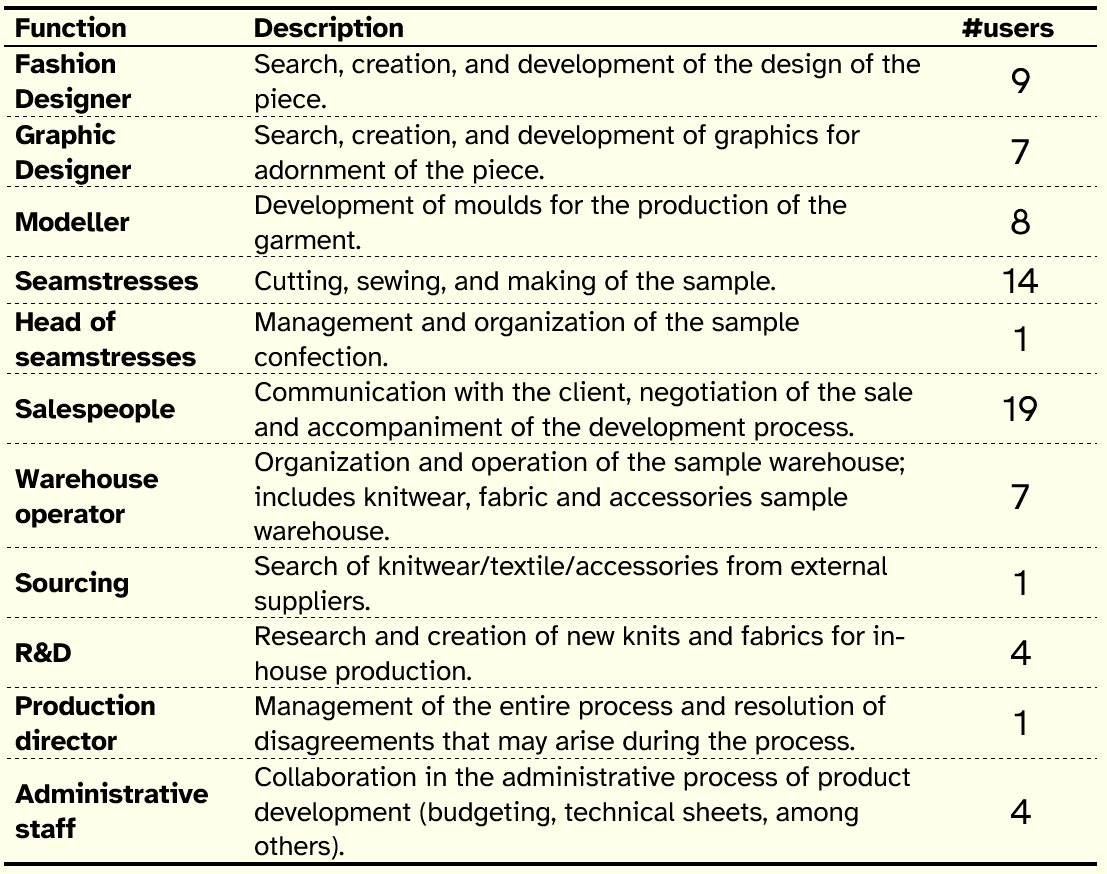

To carry out the PDP, the company makes use of various resources, namely human and material. In terms of human resources, the PDP relies on its employees and external resources. Regarding internal employees, Table 3 provides a summary of the relationship between their functions and quantities.

Table 3: Human Resources involved in the PDP

The process is organized into teams, with each team being assigned to departments according to the customers with whom the group works. Each team has at least one salesperson, one fashion designer, one graphic designer and one modeller. Eventually, when there is a department with a greater flow of work, there may be a reinforcement of employees in the functions described. In collaboration with the sales teams, there are elements that are transversal, collaborating with all the development teams, namely the

R&D team–responsible for searching and creating new knit and woven fabrics, in order to produce the bases for the development of new pieces (new compositions, weights, mixtures, among others); the sourcing team–responsible for sourcing raw materials when they do not exist internally, be it knitwear, fabrics or accessories; the operators of the samples warehouse, both for fabric and knitwear–responsible for organizing the materials and preparing the quantities requested by the developers; and the seamstresses of the samples production–responsible for making the samples.

In what concerns material resources involved in the process, the raw material for garment manufacture and the operational resources that will support the employees involved in the process must be addressed. In relation to raw materials, the general components handled in the PDP are knitwear, fabrics, and accessories. The operational resources to make the garments, such as sewing machines, will also be used, as well as computers running creative development software.

Regarding the periodicity of the process, it is characterized by its variability, following the volatility of the market in which it is inserted. Thus, it is difficult to predict or estimate the time interval in which a new development will be necessary. The process was monitored over the time. Development requests were formalized in the form of collections of 15 to 30 models, with an interval of approximately 15 to 20 days. According to the employees involved, this is an adequate estimate of their periodicity, but it should not be taken as stationary, given its intrinsic instability.

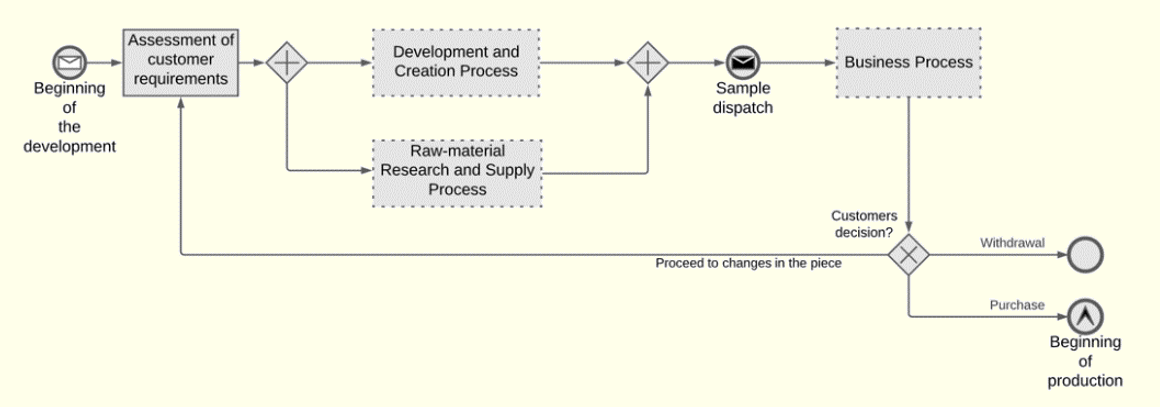

4.2 General Process

Maintaining its core business in the garment trade, the creative development of new designs and products is essential for the company production activity, and consequently, its survivability. This process consists of a preliminary stage to production, in which the creative development teams, together with the sales teams and all other stakeholders, create and negotiate the piece with the customer, in order to result in a purchase and therefore start the group’s production process. Throughout this process, the design of the garment, its patterns, its textile material, its accessories, and the details of its manufacture will be defined, according to the customer’s wishes, following a cyclical process until final approval, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: General Overview of PDP

Given the complexity of the PDP, it was important to categorize the activities in three sub processes Product Development and Creation Process, Business Process and Raw Material Search and Supply Process. As mentioned, the process begins with a contact with the customer and the identification of their needs. Given that contact, the creative development process is triggered–Development and Creation Process, namely design and modelling; as well as the search for materials to compose the piece–Raw Material Search and Supply Process. This process culminates in the confection of the sample, which will be sent to the customer. The next step depends on the customer’s decision: to make changes to the garment (and thus start a new development cycle); to buy the garment (and start the production process) or to give up the development (and terminate the process). Each of these processes were modelled using BPMN, highlighting the dynamics between the different participants in the process.

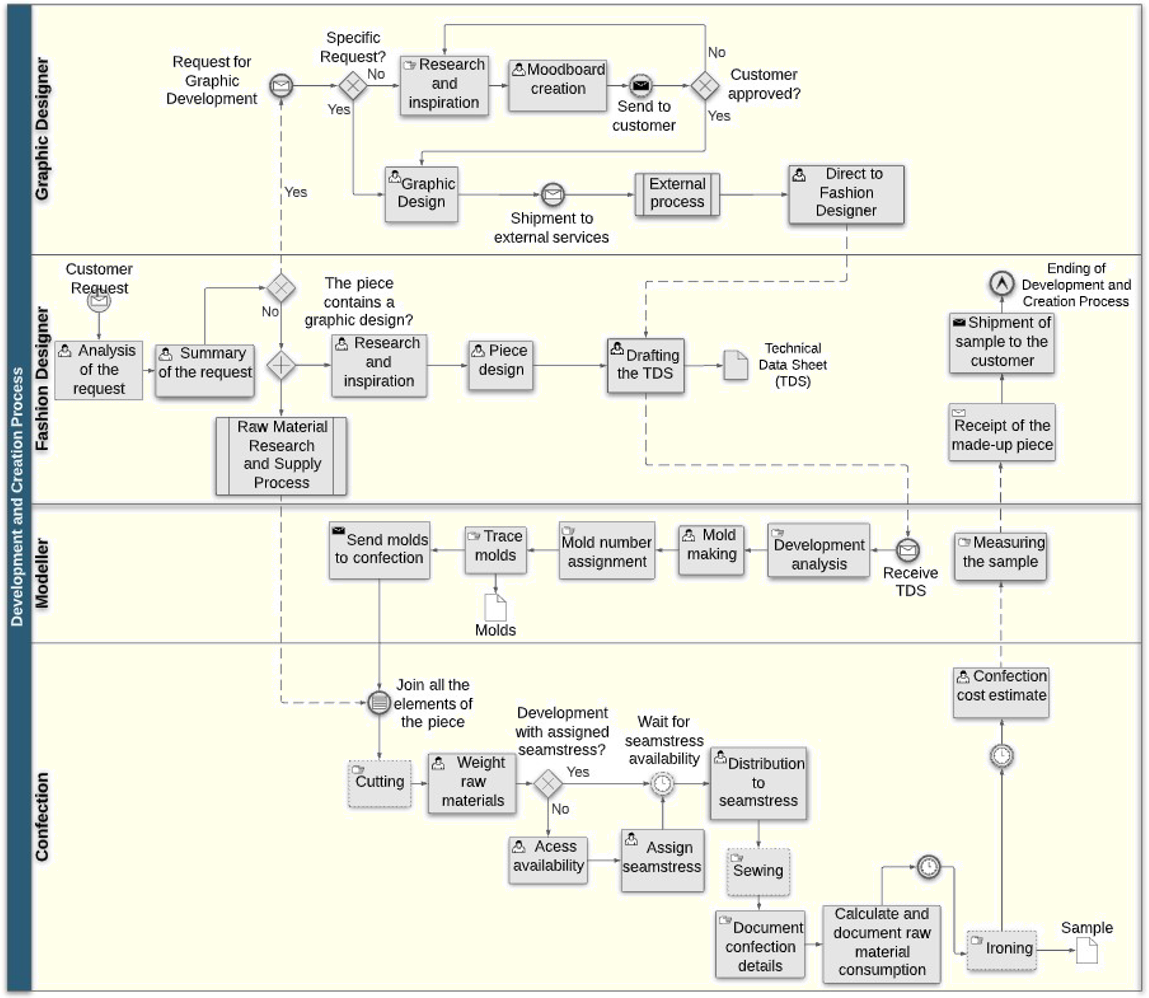

Development and Creation Process

This is the most creative part of the process, which relies on the support of various collaborators who aim to create the concept of the garment and explore their creative abilities to do so. It involves fashion designers, graphic designers, modellers, and confection. Figure 4 depicts the process at a general level.

Figure 4: BPMN—Development and Creation Process

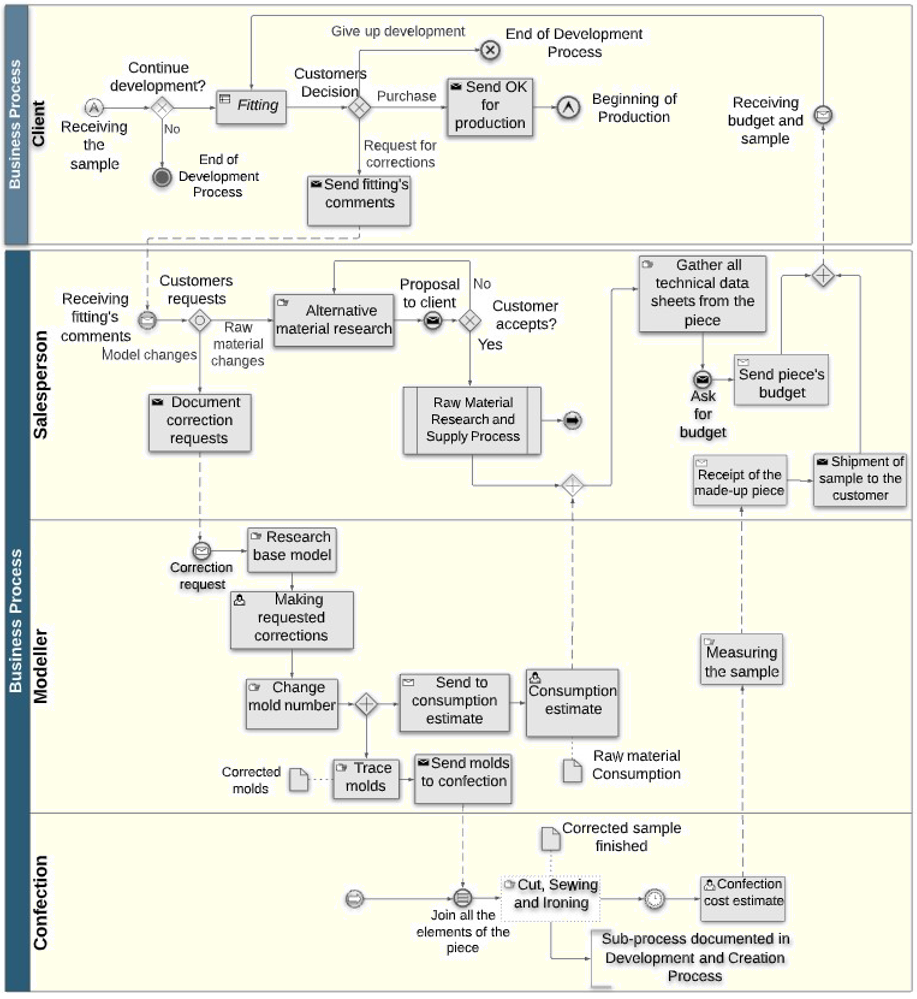

Business Process

Regarding the business process, its main focus is the role of the salesperson. It is through him that customer’s wishes are discussed and worked on, until the developed item is purchased. Figure 5 displays the BPMN structure of this activity.

Figure 5: BPMN—Business Process

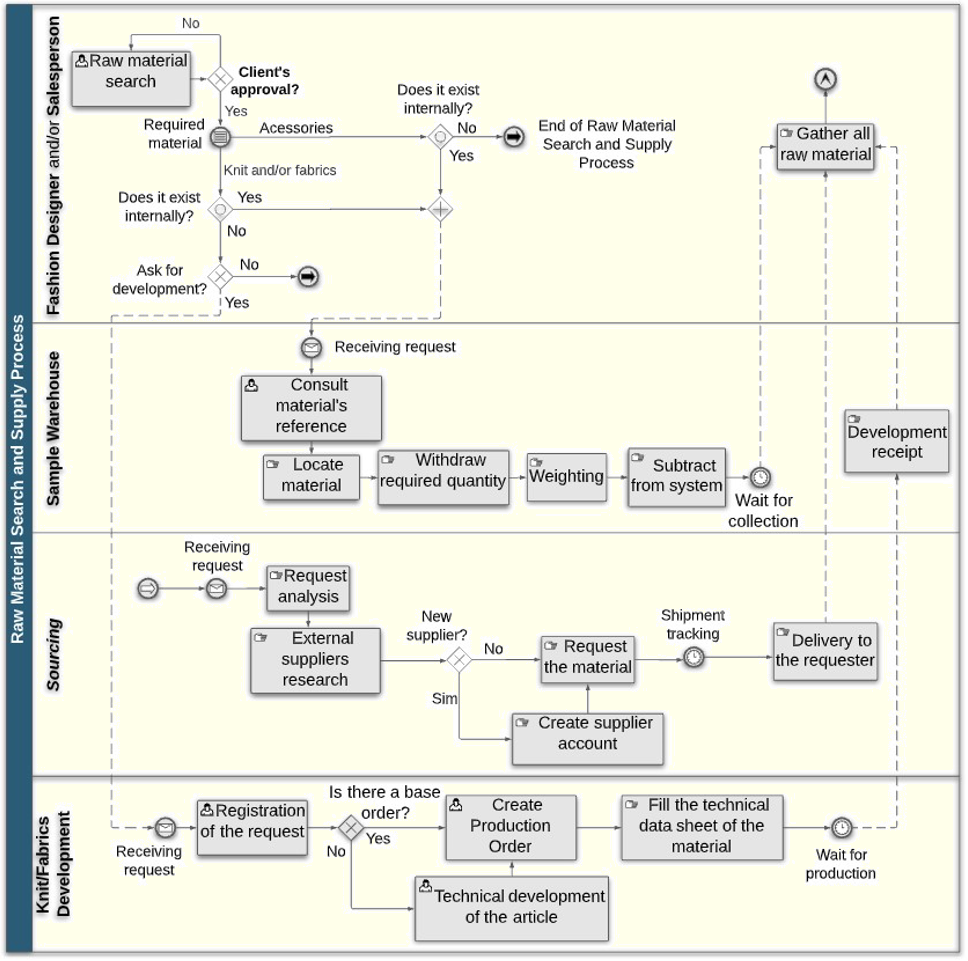

Raw Material Search and Supply Process

Finally, it becomes essential to address the Raw Material Search and Supply Process (Figure 6) where the activities required to supply the components necessary for the part are represented, with a highlight to the users of sample warehouses, as well as to the sourcing and the R&D department.

Figure 6: BPMN—Raw Material Search and Supply Process

4.3 Discussion

In this section, we identify and discuss the main lessons learned from the development of this work, which aimed at understanding the working environment in the PDP, in order to identify its key processes, diagnose its main problems, and find out opportunities for improvement.

The PDP analysed in the case of study is weakly formalized and controlled, being in an embryonic state regarding its maturity in efficiency. Thereafter, there is a need for action in order to spot possible opportunities for improvement. Indeed, the monitoring of the agents of the DPD and the mapping of their roles and activities, made possible the assimilation of crucial problems whose mitigation was required. Among these problems, the dispersion of information in the process, the informal working method and procedure, and the lack of visibility of the process stand out. These characteristics can be observed through the BPMN diagrams where, for example, the various documents that circulate in the process are represented, showing the dependence on paper and the possibility of misinterpreted information, as well as the difficulty of sharing information between different contributors to the process, represented by the diagram’s lanes.

With regard to the dispersion of information, this is due to the existence of multiple communication channels, often even in the employees’ personal communication channels, making it impossible to maintain a communications history and to record information. Additionally, the use of paper, as a method of transmitting information, increases the dispersion of information and the transmission of incorrect information due to misinterpretation. The informal working method, with no standard working procedures, is also a critical problem in the process. This problem is verified, for example, in the inexistence of task management processes and the lack of process control points. Finally, the lack of visibility of the process status is also a major problem in PDP. Both from the perspective of visibility of the state of a development, and from the perspective of visibility of all the developments occurring at the moment and historically. As for the status of a development, the lack of visibility leads to a constant need to query other users to understand at what stage the development is, interrupting their work and consequently decreasing productivity. Additionally, the lack of visibility of all the work is worrying in two ways: the first being the lack of understanding of all the work being developed at the moment, preventing the management of priorities; and the second being the lack of a record of all the work already developed, hindering data analysis and consequently the management and performance control of the process.

The PDP was performed without standardization, leading to disperse working methods. However, the need and the benefits of introducing new practices in PDP were recognized by employees and management. Regarding the life cycle of a PDP, the process scrutinized in this study was limited to the actual product development, excluding any pre-development and post-development phases, corresponding respectively to the initiation/planning, and closing of the process, therefore disregarding the potential benefits of each of those phases.

5. Conclusion

The purpose of this work was to diagnose and analyse PDP practices in the TCI, modelling the PDP of the case of study, in order to identify improvement opportunities and provide context to adopt practices that improve its functioning. The participant observation of the employees’ routines, with the objective of mapping the PDP, enabled a closer look of those involved in the process, which facilitated the understanding and documentation of their practices and concerns.

As known, case studies intend to provide insight in a specific case, so it has its limitations since the findings of this paper may not correspond to the reality of PDP processes in all CTI and therefore this point should be emphasized. Accordingly, the next step would be to perform the same study in other manufacturers, making it possible to assess comparative lines between the various organizations and be able to create a management model adapted to the sector where they operate, and then create common metrics and performance indicators that allow the performance of the process to be critically evaluated.

At this case study, product development took place without method and standardization. According to what was mapped throughout this work, it is noted the division of new product development into three macro processes: the Development and Creation Process (where the graphic and fashion designers develop their work), the Business Process (mainly explored by the salespeople with the help of administrative technicians) and the Raw Material Search and Supply Process (carried out by all internal and external raw material suppliers). These processes are carried out, in general, in a manual way and with dependence on paper, with no standardized processes throughout its development.

This work contributes to the adoption of practices that enhance the efficiency of the PDP in the TCI, increasing the knowledge about its activities, so that improvement opportunities might be identified and seized upon.

Acknowledgement

This work has been supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia within the R&D Units Project Scope: UIDB/00319/2020.

References

ABPMP (2013). BPM CBOK Versão 3.0: Guia para o Gerenciamento de Processos de Negócio.

ATP (2019). Portuguese Textile Indicators. Accessed: Jan. 09, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://atp.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Indicadores-de-Gestão-Atualiz.-Relatorio-19-06-2019.pdf.

Bhardwaj, V. and A. Fairhurst (2010). Fast fashion: Response to changes in the fashion industry. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 20(1), 165–173. DOI: 10.1080/09593960903498300.

vom Brocke, J. and M. Rosemann (2014). Handbook on Business Process Management, second edition. Springer.

CITEVE (2012). Indústria Têxtil e do Vestuário: Roadmap para a Inovação 2012-2020. CITEVE: Vila Nova de Famalicão.

Cardoso, C. and V. Quelhas (2018). Indústria Têxtil e de Vestuário—uma referência a nível mundial. Portugal Global, 12–23.

Ciaramella, A., M. G. C. A. Cimino, B. Lazzerini and F. Marcelloni (2009). Using BPMN and tracing for rapid business process prototyping environments. Proceedings of ICEIS 2009—11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems. DOI: 10.5220/0002005002060212.

Crowe, S., K. Cresswell, A. Robertson, G. Huby, A. Avery and A. Sheikh (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 11(1), 1–9. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100.

Dapiran, P. (1992). Benetton—Global Logistics in Action. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 22(6), 7–11. DOI: 10.1108/EUM0000000000416.

Harrington, J. H., E. K. C. Essling and H. van Nimwegen (1997). Business Process Improvement Workbook: Documentation, Analysis, Design, and Management of Business Process Improvement.

Kahn, K. B., S. E. Kay, R. J. Slotegraaf and S. Uban (2013). The PDMA Handbook of New Product Development, third edition.

Moretti, I. C. and A. Braghini Junior (2017). Reference model for apparel product development. Independent Journal of Management & Production 8(1), 232–262. DOI: 10.14807/ijmp.v8i1.538.

OECD and Eurostat (2005). OSLO Manual—Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data. Third.

OMG (2013). Business Process Model and Notation. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-33155-8.

Panwar, J. and D. Bapat (2007). New Product Launch Strategies: Insights from Distributors’ Survey. South Asian Journal of Management 14(2), 82.

Parker-Strak, R., L. Barnes, R. Studd and S. Doyle (2020). Disruptive product development for online fast fashion retailers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 24(3), 517–532. DOI: 10.1108/JFMM-08-2019-0170.

Rosenfeld, H., F. A. Forcellini, D. C. Amaral, J. C. de Toledo, S. L. da Silva, D. H. Alliprandini and R. K. Scalice (2006). Gestão de Desenvolvimento de Produtos—Uma Referência para a Melhoria do Processo. São Paulo, Brasil: Editora Saraiva.

von Rosing, M., H. von Scheel and A. W. Scheer (2014). The Complete Business Process Handbook: Body of Knowledge from Process Modeling to BPM, Volume 1.

Saunders, M., P. Lewis and A. Thornhill (2008). Research Methods for Business Students, fifth edition. Edinburgh: Pearson Education Limited.

Senanayake, M. (2015). Product Development in the Apparel Industry, Volume 2. Elsevier.

Smith R. P. and J. A. Morrow (1999). Product development process modeling. Design Studies 20(3), 237–261. DOI: 10.1016/s0142-694x(98)00018-0.

Tran, Y., J. Hsuan and V. Mahnke (2011). How do innovation intermediaries add value? Insight from new product development in fashion markets. R&D Management 41(1), 80–91. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9310.2010.00628.x.

Ulrich, K. T. and S. D. Eppinger (2016). Product Design and Development, sixth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

WRI (2017). The Apparel Industry’s Environmental Impact in 6 Graphics. World Resources Institute, 2017. https://www.wri.org/insights/apparel-industrys-environmental-impact-6-graphics (accessed May 27, 2021).

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research: Design and methods, sixth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.