Original source publication: Dhillon, G., R. Syed and F. de Sá-Soares (2017). Information Security Concerns in IT Outsourcing: Identifying (In)congruence between Clients and Vendors. Information & Management 54(4), 452–464.

The final publication is available here.

Information Security Concerns in IT Outsourcing: Identifying (In)congruence between Clients and Vendors

a Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

b University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA, USA

c Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

Abstract

Managing information security in Information Technology (IT) outsourcing is important. We conduct a Delphi Study to identify key information security concerns in IT outsourcing. A follow-up qualitative study was also undertaken to understand (in)congruence between clients and vendors with respect to the top information security concerns. In a final synthesis, our study found three central constructs to ensure information security in IT outsourcing: 1) competence of the vendor to ensure information security; 2) compliance of the vendor with client requirements and external regulations; and 3) trust that proprietary information is not abused and that adequate controls are in place.

Keywords: Information Security; Information Technology Outsourcing; Congruence; Delphi Study; Qualitative Interviews

1. Introduction

Globalization requires that organizations transcend national boundaries to collaborate among distributed teams. Such global collaborations have transformed organizational structures around virtual teams, offshoring, outsourcing, and open sourcing [Agerfalk and Fitzgerald 2008]. However, information security is a significant sticking point in establishing a relationship between Information Technology (IT) outsourcing vendors and clients. While statistics related to outsourcing risks and failures abound, there has been a limited emphasis on understanding information security concerns in outsourced projects from both client and vendor perspectives (see [Gonzalez et al. 2006] and [Lacity et al. 2010]). We argue that information security incongruence stems from the lack of fit between what IT outsourcing vendors consider to be the key success factors and what outsourcing clients perceive to be critical for the success of the relationship. It is important to undertake such an investigation because of two primary reasons: (1) There is a problem with the appreciation of the context within which IT vendors and clients operate. A majority of IT outsourcing projects fail because of a lack of appreciation as to what matters to the clients and the vendors [Barthelemy 2001; Kaiser and Hawk 2004]. (2) Lack of congruence often leads to broken processes and misaligned priorities, which are a consequence of an organization’s inability to manage the IT vendor-client relationship [Earl 1996]. We study the information security incongruence problem through the following research questions:

What are the key information security concerns that IT outsourcing clients and vendors face?

What is the extent of (in)congruence between IT outsourcing clients and vendors with respect to the top ranked information security concerns?

There are two classes of definitions that need clarity. First, in our research IT outsourcing refers to the arrangement between a client and a vendor

firm where a vendor may provide information technology related services to the client organization [Lacity and Willcocks 1998]. Second, in our research information security refers to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information or intellectual property pertaining to client and vendor firms engaged in IT outsourcing projects (see [Chowdhuri 2012] for a detailed review). In the context of this research, we are concerned with the nature and scope of information security concerns in ongoing IT outsourcing arrangements between clients and vendors.

In this paper, we present an analysis of a two-phase study to investigate the extent of (in)congruence between outsourcing clients and vendors. In the first phase, we conduct an extensive Delphi Study to identify major information security concerns in outsourced projects. We rank the information security concerns to identify the priorities of the clients and vendors for the concerns. In the second phase, we conduct an intensive analysis of the concerns through in-depth interviews with several client and vendor firms. Based on the analysis, we define a framework to ensure information security in IT outsourcing.

2. Informing Literature

In this research, we are informed by the mainstream IT outsourcing literature. Within this literature, we are particularly interested in research that has focused on identifying information security concerns. Such research falls into two broad categories: research focusing on relationships between clients and vendors and research focusing on outsourcing risk assessment.

One of the limitations of the Bachlechner et al. [2014] study is the a priori identification of the information security challenges. The challenges are too specific to ensure compliance with service level agreements. Liu et al. [2014] make some progress in this regard by developing a vendor selection method, which is based on security service level agreement. In a final synthesis, the authors present an automated algorithm for ranking trust levels. While this may be a very useful tool, problems arise with the identification of security terms in service level agreements. In some cases, the problem is the service level agreement itself. Clients and vendors interpret the contractual agreements differently and despite corrective actions, fail to rescue the outsourcing arrangement (see [Moe et al. 2014]).

The existing research on outsourcing risk assessment notes several factors that pose risks to IT outsourcing arrangements. For example, Internet Security has been considered as one of the technological risks [Kern et al. 2002], with data confidentiality, integrity, and availability as the topmost concerns in an outsourcing arrangement [Khalfan 2004]. Few surveys also report computer networks, regulations, and personnel as the highest security threats to organizations [Chang and Yeh 2006]. Other surveys recognize that not only technical but also non-technical threats can be detrimental to an outsourcing engagement [Chang and Yeh 2006; Dlamini et al. 2009; Pai and Basu 2007]. Some studies note that the influence of non-technical concerns such as employees, regulations, and trust is more severe than technological risks [Loch et al. 1992; Posthumus and von Solms 2004; Tickle 2002; Tran and Atkinson 2002]. As such few studies are concerned with a specific type of security concern such as security policies [Fulford and Doherty 2003]. Although these studies increase our understanding of the potential risks in IT outsourcing, there is limited focus on information security concerns from both client and vendor perspectives [Earl 1996; Sakthivel 2007].

Gonzalez et al. [2006] note that a majority of IT outsourcing topics are researched from four perspectives: clients, providers, relationship, and economic theories. Their analysis suggests that the outsourcing success factors and risks have received attention only from a client perspective. In another study, Lacity et al. [2010] identify information security as a common IT outsourcing risk, which could potentially be a cause of discordance between clients and vendors. However, the majority of other concerns deal with business risks that range from backlash from internal IT staff, breach of contract, lack of trust to issues of supplier power, turnover, and burnout.

Several researchers have also proposed frameworks to identify organizational assets at risk and financial metrics to determine the priority of assets that need protection [Bojanc and Jerman-Blažic 2008; Osei-Bryson and Ngwenyama 2006], Likewise, Doomum [2008] presented a multi-layer security model to mitigate the security risks, both at a technical and nontechnical levels, in outsourcing domains. Doomum’s framework arranges eleven steps in an outsourcing arrangement across three layers of security: identification; monitoring; and improvement and measurement. Although the proposed framework can be useful to identify, monitor, and evaluate information security risks in outsourcing arrangements, it lacks empirical validation. Furthermore, the framework is process-centric, focusing on how to manage information security rather than what needs to be managed. Wei and Blake [2010] provide a comprehensive list of information security risk factors and corresponding safeguards for IT offshore outsourcing. However, the issues have mainly been borrowed from the existing literature and lack empirical validity. More recently, Nassimbeni et al. [2012] proposed an assessment framework to identify security risk profiles of companies involved in outsourcing and offshoring IT projects. Their framework offers insights to manage intellectual property security risks in service outsourcing. The authors argue that unlike previous studies that focus on a single aspect of security, their framework provides a holistic analysis of security at technical, legal, and managerial levels. Although their framework could be very useful to understand security issues during different phases of outsourcing (e.g., strategic planning, supplier selection and contracting, and implementation and monitoring), it suffers from the lack of understanding in the existing literature about the security aspects [Nassimbeni et al. 2012].

We conclude that although there is a rich body of research on IT outsourcing, the literature has some deficiencies. First, several studies have highlighted the importance of client-vendor relationship [Bachlechner et al. 2014; Lacity et al. 2010], but not enough attention has been paid to the lack of appreciation of information security, which in turn could threaten the client-vendor relationship. Second, the research related to risk analysis mainly focusses on conceptual frameworks for managing risk factors and does not offer insights about the aspects of information security that need to be managed. Furthermore, few studies consider information security as one of the many types of risks in IT outsourcing (e.g., Lacity et al. [2010]). Our study identifies the information security concerns from both client and vendor perspectives and empirically assesses the (in)congruence between clients and vendors.

3. Research Methodology

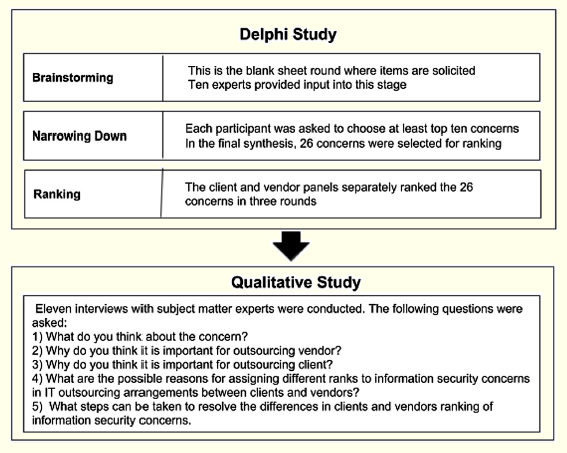

In this research, we used the Delphi technique to identify important information security concerns pertinent to an IT outsourcing relationship. We followed up by undertaking in-depth qualitative interviews with the subject matter experts to understand the differences in the rankings obtained from IT outsourcing clients and vendors. The schematic illustrating the methodological steps in presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sequence of Methodological Steps

3.1 The Delphi Study

The objective of this study is to develop a comprehensive list of key information security concerns in IT outsourcing and to understand the (in)congruence between clients and vendors for information security concerns in IT outsourcing. One of the approaches to elicit data is to engage a panel of experts who have significant knowledge and experience in IT outsourcing and information security. The Delphi method is a suitable way to elicit the opinions of the panels of experts through iterative feedback-based convergence and, identify and rank the concerns in order of importance. Delphi technique has some distinct advantages over other ranking methods. Okoli and Pawloski [2004] discuss the strengths and weaknesses of Delphi method with respect to other ranking approaches. In this study, we applied the Delphi method because of the following five reasons:

Delphi method allows to inquire and seek the divergent opinions and experiences of different experts and translate those into a reliable and validated list of information security concerns for both client and vendor organizations.

We employed a ranking method based on Schmidt’s Delphi methodology to elicit opinions of panels of experts through controlled inquiry and feedback [Schmidt 1997]. Delphi study allowed information security concerns to converge to the ones that are important for clients and vendors in IT outsourcing.

Delphi method is suitable if the participants are not co-located. The researchers collected data from global experts.

The findings from Delphi permitted us to conduct the second phase of the research inquiry leading to richer data collection and understanding of information security concerns in IT outsourcing.

As previously stated, there is a lack of knowledge about information security concerns in IT outsourcing and the importance of the concerns for clients and vendors. The Delphi method allowed us to understand the concerns from both client and vendor perspectives.

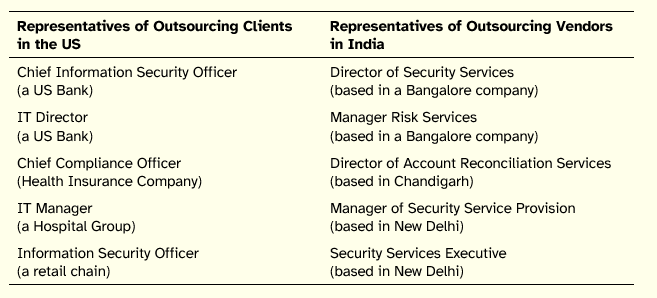

To select the participants, we started out by identifying existing outsourced arrangements between firms in the US and India. In our initial screening, we identified six companies in the US (two major banks, two healthcare companies, a hotel conglomerate, and a retail company), which had ongoing outsourcing arrangements with Indian counterparts. Indian vendor firms were located in three major cities—Bangalore, Chandigarh, and New Delhi. To account for the maximum diversity regarding the roles and experiences of globally distributed teams, we reached out to the senior executives for identifying and nominating subject matter experts. We dropped one of the dyadic arrangements because of the lack of participation by the nominated individuals. In the final count, we had 11 experts representing five firms in the US and five firms in India. The experts were divided into two panels—Outsourcing Clients (5) and Outsourcing Vendors (5). All experts had substantial experience in cross-border collaborations as well as in information security. The profile of our panelists is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Profile of Delphi Study Panelists

Our sample size conforms to the suggestions made by other scholars. For example, Schmidt [1997] suggests limiting the number of participants between 9 and 12 so as to prevent them from being intimidated with the feedback generated during ranking rounds. Likewise, Okoli and Pawlowski [2004 recommend a group size of 10 to 11 as the results are dependent on group dynamics rather than group size. Furthermore, the experts in this study represented multiple industries that allowed us to focus on the generic information security concerns in IT outsourcing rather than the concerns specific to a particular industry.

Based on Schmidt’s approach, data was collected in three rounds [Schmidt 1997]. In the first round, known as brainstorming or blank sheet round, the experts were asked to list at least six security concerns inherent to outsourced collaborations along with a short description of each concern. The authors collated the concerns by removing duplicates. The combined list was sent to the experts explaining why certain items were removed and further asked the experts for their opinion on the integrity and uniformity of the list. In the second round, we asked each expert to pare down the list to the most important concerns. The refined list was shared with the experts; reasons for merging or deleting a concern were provided. The authors sought a consensus on the final list of concerns so that a common agreed upon set of concerns are ranked in the subsequent rounds. In each round, the authors reduced the number of concerns to ones that were highly ranked for maintaining quality and preventing participant fatigue (see [Judd 1972] and [Schmidt et al. 2001]). Informed by Schmidt et al. [2001], experts were asked to choose at least ten concerns that they considered important in outsourced collaborations. The concerns that were chosen as important by more than half of the experts, i.e. concerns with a mode of > = 5 were retained, reducing the total number of concerns to 26. Ranking of the final 26 concerns was done in phase 3. The experts were divided into two panels: client and vendor. During this phase, each expert was required to rank the concerns in order of importance with 1 being the most important information security concern and 26 being the least important information security concerns in IT outsourcing. The panelists were restricted to have ties between two or more concerns.

3.2 Qualitative Interviews

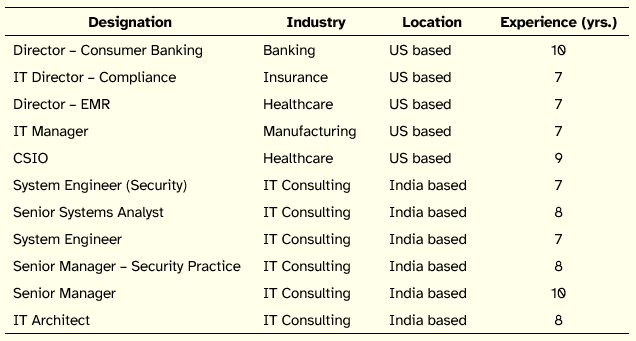

The second round of data collection was based on several qualitative interviews with representatives from Fortune 500 companies. These individuals were different from those in the Delphi study. A convenience sample of over two dozen companies, which had a relationship with the business school of one of the authors, was drawn. All individuals represented major corporations, which had ongoing outsourcing relationships with international vendors. To ensure that our interviewees had familiarity with information security concerns, we used two screening questions to narrow down the list of participants. These questions were: Have you ever been involved with an IT outsourcing project? Have you ever had to take decisions about protection of sensitive information in an IT outsourcing project? Fifteen of the twenty-four shortlisted individuals met the criteria. Finally, eleven agreed to participate in the study. The eleven participants had an average experience of about eight years and represented banking, insurance, healthcare, manufacturing, and consulting sectors. Five of the eleven worked for US based IT vendor firms. Table 2 summarizes the profile of the interviewees.

Table 2: Profile of Qualitative Interview Participants

Each participant was required to answer three questions for all 26 concerns: (1) What do you think about the concern? (2) Why do you think it is important for an outsourcing provider? (3) Why do you think it is important for the outsourcing client? Suitable probes were added following each question. This helped in developing a rich insight. Our interviews also focused on understanding the lack of congruence between outsourcing clients and outsourcing vendor with respect to the information security concerns. We shared the ranks obtained from the Delphi study with our participants. Two questions, with suitable probes, were asked to elicit their opinions on the gaps between the client and vendor rankings of the information security concerns: (1) What are the possible reasons for assigning different ranks to the information security concern in IT outsourcing arrangements between clients and vendors? (2) What steps can be taken to resolve the differences in clients and vendors ranking of the information security concerns? The findings are discussed in the next section.

4. Ranking of Information Security Concerns in IT Outsourcing

In this section, we present the results of Delphi study in two subsections. The first subsection presents the full list of the information security concerns in IT outsourcing identified by both clients and vendors. The second subsection presents rankings of the information security concerns provided by clients and vendors panels.

4.1 Identification of Information Security Concerns

The first objective of this study is to develop a comprehensive list of key information security concerns encompassing both clients and vendor perspectives. Our research found twenty-six concerns related to information security in IT outsourcing relationships. A brief discussion of these concerns follows in no specific order. We also discuss each concern in relation to the existing research.

Concern C1: Ability of outsourcing vendor to comply with client’s security policies, standards, and processes. An organization that wishes to outsource IT operations needs to view its security policies, standards, and processes being largely applied by the vendor, with some minor adaptations as needed. A large body of literature about employee compliance with information security policies have emerged over the years. Our research relates to the literature of employee awareness and intentions to comply [Bulgurcu et al. 2010; Herath and Rao 2009].

Concern C2: Audit of outsourced information technology operations. The outsourcing clients expect to have access to a clear audit trail of important and sensitive events and activities. Research shows that audit is one of the useful means for providing information about the occurrence of an undesirable event [Aubert et al. 2005].

Concern C3: Audit of outsourcing vendor’s staffing process. The outsourcing clients should be able to audit the staffing process of the outsourcing vendors. Our participants expressed concern that vendors could recruit good IT staff in the initial days of the contract but over a period loosen the quality of staff, over which clients do not have much control. In their study, Kern and Willcocks [Kern and Willcocks 2002] report that third-party audits discovered that vendors deliver the services as per the agreement, however, anomalies existed at multiple levels, including quality of staff.

Concern C4

Concern C5

Concern C6: Congruence between outsourcing vendor’s and client’s cultures. It refers to the cultural differences or similarities between the outsourcing vendors and clients in how the security policies and standards are embedded and enacted. Da Veiga and Eloff [2010] note that an information security-aware culture minimizes the risk of employee misbehavior and harmful interaction with information assets.

Concern C7

Concern C8: Dissipation of outsourcing vendor’s knowledge. An outsourcing vendor that has high staff rotation may experience a higher risk of knowledge dissipation, thus affecting the quality of the information security services provided to the client. Inkpen and Crossan [1995] regard the exchange of knowledge between strategic partners important for organizational learning, the absence of which could cause eventual knowledge dissipation.

Concern C9: Diversity of jurisdictions and laws. If the outsourcing vendor operates in a context with different international laws and jurisdictions, this may raise information security issues, such as the impossibility to release data to foreign workers employed by the vendor. Previous research reports similar concerns in IT outsourcing causing violations of conformance and contractual requirements [Pai and Basu 2007].

Concern C10: Failure of an outsourcing vendor to have in-depth knowledge of client’s business processes. The outsourcing vendor may fail to acquire in-depth knowledge of the client’s business processes and systems, which could prevent the vendors to provide innovative information security solutions. The need and mechanisms to support the effective knowledge transfer from clients at onshore locations to vendors at offshore locations are highlighted in the existing research (e.g. [Williams 2011]).

Concern C11: Financial viability of information technology outsourcing. Exposing intellectual property and company reserved data to any third party leads to an extra cost of introducing additional security measures that can make IT outsourcing financially unviable. Scholars argue that before establishing IT outsourcing relationship, the clients and vendors should ensure the long-term financial and managerial viability, the absence of which could abruptly exit the relationship [Miranda and Kavan 2005].

Concern C12: Governance ethics of outsourcing vendor’s context. Our client panelists were concerned if the outsourcing vendors operate in a context of trust, probity, and free from corruption. Meng et al. [2007] argue that effective service governance for both service outsourcers and service providers determine the success of IT outsourcing.

Concern C13: Inability to change information security requirements. Once IT services have been handed over to an outsourcing vendor, the outsourcing client may be unable to change information security requirements. Since the vendor may request project extensions, bill additional hours or out rightly reject the required changes, the outsourcing contract may get renegotiated. However, existing research acknowledges the need and challenges to elicit and integrate changing security requirements [Khalfan 2004]. Frameworks for security requirements engineering have also been suggested [Halley et al. 2008].

Concern C14: Inability to harness business knowledge on subsequent projects. Since the outsourcing client has no control of specific outsourced organizational resources, it is difficult to apply business knowledge and lessons learned on subsequent projects, which are then completed purely on a task to task basis without guarantee of quality and standards compliance. Existing literature notes that both clients and vendors need to understand the importance of knowledge management, implications of the loss of knowledge, and the structural requirements to maintain knowledge [Willcocks et al. 2004].

Concern C15: Inability to redevelop competencies on information security. Once an organization has outsourced IT, it will be difficult for the organization to develop competencies to insource information security in its IT systems. In one of the earlier research, Aubert et al. [1998] note the undesirable consequences of IT outsourcing. They argue that loss of organizational competencies involves loss of IT expertise, loss of innovative capacity, loss of control of the activity, and loss of competitive advantage.

Concern C16: Information security competency of the outsourcing vendor. When an organization looks to outsource IT, it should check the skills possessed by the outsourcing vendor in information security. The vendor should have a proven disciplined approach to security, including processes to identify and control security risks, policies and technological mechanisms to protect data, application of information security best practices, etc. Several scholars note that the vendor competence, in general, is important for outsourcing success [Willcocks et al. 2000], and the vendor competence to secure a client’s intellectual and informational assets is regarded as one of the decision factors to outsource [Yang et al. 2007].

Concern C17: Information security credibility of outsourcing vendor. As outsourcing vendor should be able to provide evidence, track record, external audit reports or certifications against standards in building and operating development and data processing events that have sufficient high-quality security controls. Information security management guidelines are used by organizations to demonstrate their commitment to security, apply for certification, accreditation, or a security-maturity classification [Siponen and Willison 2009]. However, much of the guidelines are generic and do not account for differences between organizations and the varying security requirements.

Concern C18: Legal and judicial framework of outsourcing vendor’s environment. This concern means that if the outsourcer operates in an environment with a sound framework of law and justice, which may be able to ensure proper enforcement of contract clauses regarding issues like data confidentiality. In the literature, several calls have been made that suggest clarity of legal and regulatory frameworks (e.g. [Raghu 2009]).

Concern C19: Legal and regulatory compliance. An outsourcing client who is regulated on information security and privacy (e.g., HIPAA for Healthcare, PCI for Merchants, etc.) must be able to verify that the outsourcing vendor can adequately meet and sustain those compliance needs. Dhillon et al. [2016] note that similar concerns emerge during organizational mergers. The incompatibility in the legal framework is reported to impact successful organizational transformation.

Concern C20: Quality of outsourcing vendor’s staff. This concern relates to the soundness of outsourcing vendor’s staffing processes regarding vetting, training, and monitoring of employees. Lacity and Hirschheim [1993] note several reasons for diminishing staff quality of vendors. In particular, the authors note that the vendors reduce the staff and make the remaining staff work extra hours, which makes people tired and prone to making mistakes. Moreover, vendors siphon their best employees to secure new contracts, which diminishes the overall staff quality.

Concern C21: Right balance of access. The outsourcing client needs to provide the right balance of access to the outsourcing vendor so that they can undertake their job. In the literature several techniques to provide adequate access to resources in outsourced IT projects have been proposed (e.g. [Hur and Noh 2011; Wang et al. 2009]).

Concern C22: Technical complexity of outsourcing client’s information technology operations. It may be difficult to understand the outsourcing client’s IT systems, processes, and services by the outsourcing vendor to the level necessary for identifying security vulnerabilities and breaches. Quélin and Duhamel [2003] argue that IT outsourcing operations are becoming increasingly complex as companies are increasingly outsourcing more mission-critical and complex operations. The complexity of the client’s business and systems poses severe challenges to the vendors.

Concern C23: Technological maturity of outsourcing vendor’s environment. The outsourcing clients are concerned if the outsourcing vendor operates in an environment that is technologically mature and confident. Willcocks and Kern [1998] suggest that the technical capability of vendors shape both structure of outsourcing contract and interpersonal relationship between clients and vendors.

Concern C24: Transparency of outsourcing vendor billing. The outsourcing vendor may utilize the resources of a particular client to the benefit of other clients, and the client is not guaranteed that the resources billed by the vendor are indeed used for their organization only. In their study, Lacity and Hirschheim [1993] note the service problems in outsourcing. Among many, authors note that vendors charge for low-quality resources same as that of highquality ones, bill non-productive hours such as group vendor meetings and training, and charge by hours rather than productivity.

Concern C25: Trust that outsourcing vendor applies appropriate security controls. The outsourcing clients trust that outsourcing vendors apply appropriate security controls to protect the data confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Existing research show that trust, in general, is a concern in IT outsourcing [Loch et al. 1992; Posthumus and von Solms [2004; Tickle 2002; Tran and Atkinson 2002], and a few studies indicate a lack of security in IT outsourcing as concerning [Fulford and Doherty 2003].

Concern C26: Trust that outsourcing vendor will not abuse client’s proprietary information and knowledge. The outsourcing clients trust that the outsourcing vendor will not abuse the proprietary knowledge exchanged as well as any other reserved information released required for outsourcing IT. In the literature, sharing proprietary information is reported to positively influence trust and commitment of vendors and clients [Lee 2001].

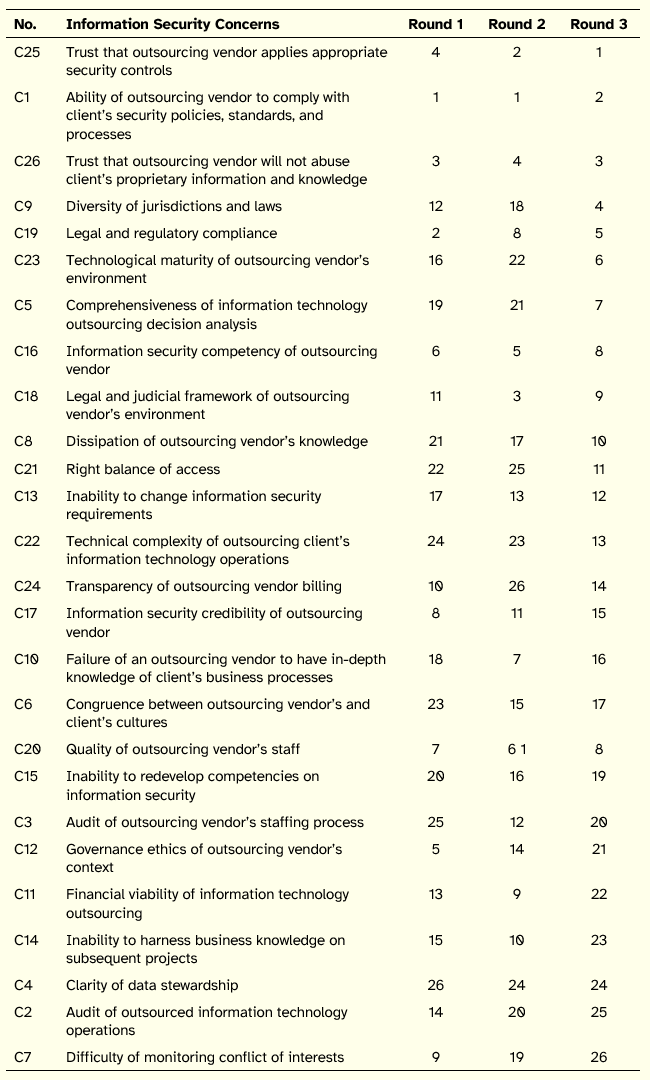

4.2 Ranking of Information Security Concerns

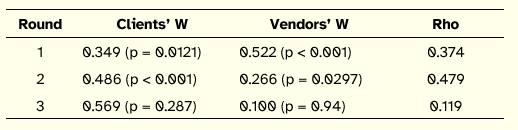

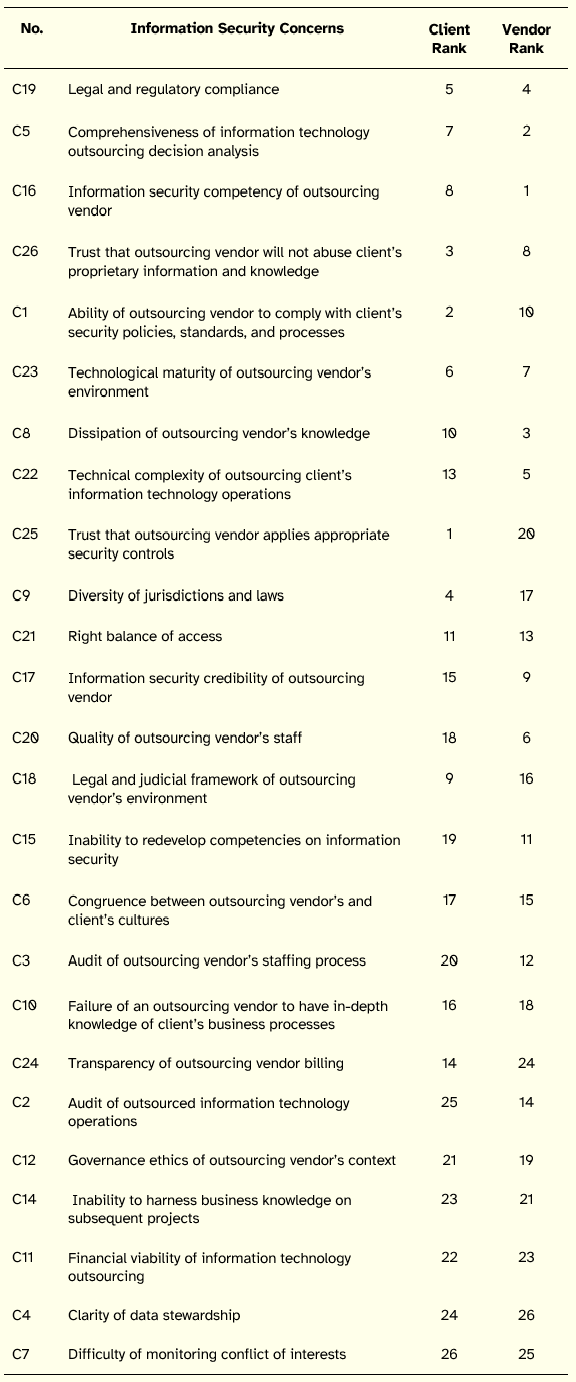

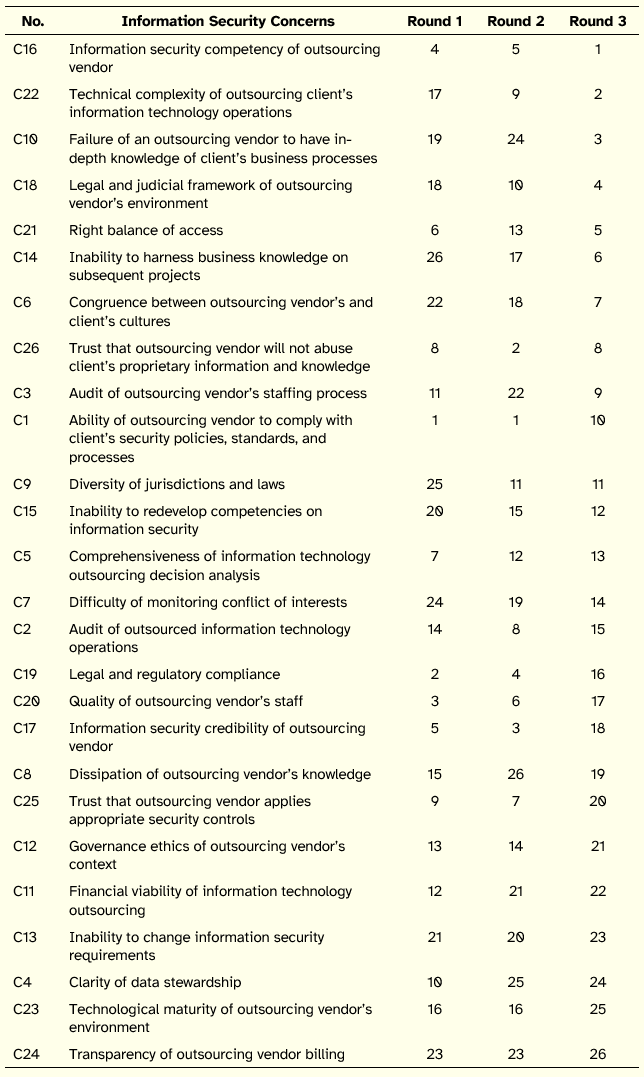

In this section, we present the analysis of the relative ranks provided by the two panels. The ranks of the concerns provided by clients and vendors panels that evolved in three ranking rounds are listed in the Appendix A. By the third ranking round, clients’ panel had a fair agreement whereas vendors’ panel had a very weak agreement. The weak consensus among vendors indicates that not all vendors perceive the importance of security at the same level. Moreover, the two panels have a weak positive correlation by round 3 (see Table 3), which suggests incongruence between the outsourcing clients and outsourcing vendors. Finally, the difference between the ranks assigned to each concern by the clients and vendors further highlights the incongruence between the two. Table 4 presents a comparison of the ranks from client and vendor perspectives and shows a significant divide between the two groups. Although the concerns are sorted compositely, the large differences between the client and vendor ranks for most of the concerns makes the composite rank less relevant.

Table 3: Client and Vendor Consensus

Table 4: Final Client and Vendor Ranks

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the findings pertaining to the two research questions of this study.

5.1 Research Question 1—What are the key information security concerns that IT outsourcing clients and vendors face?

In this section, we discuss the top three information security concerns identified by the clients and vendors. In the literature, a similar approach discussing top three concerns is also adopted by Liu et al. [2010]. We supplement the discussion with findings from indepth interviews with a panel of experts.

5.1.1 Top Three Concerns from a Client Perspective

Client Concern 1

I can say with absolute certainty that our outsourcing experience has been very positive. We found significantly high level of competence in our vendors. However, there are constant challenges of dealing with the regulatory environment. Laws in the US are rather strict regarding disclosure and we feel that to be an impediment to getting our work done.

The CIO went on to note:

One of the pressing issues in any outsourcing relationship is that of trust, yet trust needs to be verified. Given the highly regulated environment in which we function, it is important for vendors to apply appropriate [security] controls. But, we are never sure.

The literature has reported similar concerns, albeit on mainstream outsourcing issues rather than security. It has been argued that there are issues of conformance and contractual violations, which can have a detrimental impact on outsourcing relationships [Pai and Basu 2007]. Sabherwal [1999] also discusses the virtuous cycle of the structure, trust, and performance. He argues that distrust leads to poor quality.

Client Concern 2

It is great that an outsourcing vendor can claim they are competent in providing information security but it means nothing to the client unless the client perceives their specific policies as being effectively applied by the vendor.

To eliminate the gap, processes and policies need to be comprehensive enough and the contracts need to emphasize the implications of non-compliance. For the sake of continued alliance, responsibility lies more on the vendor to ensure process compliance and governance. Another manager from a client organization commented:

Clients are usually outsourcing to relieve their workload and performing a comprehensive analysis is viewed as adding to the existing workload they are trying to relieve. The more a potential vendor is willing to be an active partner and point out the pros and cons of their own proposals as well as of the others, the smaller the gap will be.

Establishing congruence between client and vendor security policies ensures the protection of information resources and a good working arrangement between the client and the vendor. Furnell and Thomson [2009] define levels of security compliance and noncompliance depending on the degree to which users deem information security important in a particular context. In terms of compliant behavior, there are four categories: culture, commitment, obedience, and awareness. At a cultural level, security becomes an implicit part of user’s behavior, whereas, at awareness level, users may be aware of the significance of security practice but don’t necessarily comply. In terms of non-compliant behavior, there are four categories: ignorance, apathy, resistance, and disobedience. While an ignorant user is unaware of security issues, a disobedient user intentionally works against security. As the characteristics of outsourced projects closely conform to those of a bureaucratic environment (see, [Weber 1978]), compliance could become a bureaucratic process with a little passion.

Client Concern 3: Trust that outsourcing vendor will not abuse client’s proprietary information and knowledge (C26). This concern is somewhat linked with the other two top most client concerns. While overall trust in instituting appropriate security controls is certainly an issue, the client organizations are even more concerned by losing their proprietary information. In the realm of the healthcare sector, loss of proprietary information can have a devastating effect, particularly because of HIPAA compliance issues. One of the Compliance Officers from a medical billing firm

noted:

We estimate medical billing costs to be at about 5% of our total costs. There is a natural tendency among small and medium-sized clinics to outsource some or all of their medical billing. However, there is also a constant worry of losing control and the possibility of a breach. Also, once we let go of our own ability to control the data, we also reduce our capability to handle such issues in the future.

While there are a few studies that focus on IT outsourcing and capability loss, there is, however, limited research on effects of proprietary information loss on the outsourcing relationship. Handley [2012] have hypothesized that more the capability loss experienced by the client firm, the more difficult and challenging it is to develop a cooperative relationship with the vendor firm. Nevertheless, findings from our study lay significant importance on loss of data by vendors as well as loss of capability by the client firm in their ability to manage information security following IT outsourcing.

5.1.2 Top Three Concerns from a Vendor Perspective

Vendor Concern 1: Information security competency of outsourcing vendor (C16). Our research found information security competency of the outsourcing vendor as a significant concern. Many scholars have commented on the importance of vendor competence [Goles 2001; Levina and Ross 2003; Willcocks and Lacity 2000]. It is argued that value based outsourcing outcome should be generated and transferred from the vendor to the client [Levina and Ross 2003]. However, as is indicative from our study, clients and vendors differ in their opinions on information security when engaging in IT outsourcing. While, vendors often believe that proving their competency through a large list of certifications, awards, and the large clientele is important to have to prove their competency, client perspective is geared towards the application and utilization of vendor competency. One of the IT managers from a bank noted:

The vendor is expected to be competent in their area of expertise, so the client needs to make clear to the vendor that a basic expectation should not be at the top of their list as there are more important factors that will be used to differentiate the vendors from one another.

As is rightly pointed out by the IT Manager, the issue with managing competence is not to present a baseline of what the vendor knows (i.e. the skill set), but a demonstration of the know-that (see [Dhillon 2008]). Assessment of competence is outwardly driven and hence a presentation of some maturity in security management is essential (e.g. ISO 21827). A competence in ensuring security is to develop an ability to define individual know-how and know-that. In the literature, Information Security Competence Maturity Model is proposed to measure the extent of provisions for information security in an organization [Thomson and von Solms 2006]. Such a model could serve as a benchmark to assess the competence of vendors.

Vendor Concern 2: Comprehensiveness of information technology outsourcing decision analysis (C5). Our research found that vendors expect the client organizations to have a comprehensive approach in their outsourcing efforts. A piecemeal approach tends to leave vendors wondering how the outsourcing relationship will proceed. Clients, on the other hand, seem to have a different view. Managing control of the data and implementation of appropriate controls seems to help build trust. One of the managers from a vendor firm noted:

In the literature, similar concerns have been noted. Dunkle [1996] discusses this aspect in the context of outsourcing of a library cataloging process. It is difficult to accurately predict security requirements in an IT outsourcing relationship. Hence, some clarity in the decision process is required. Similarly, Goo et al. [2007] found that decision uncertainty impacted the duration and quality of the IT outsourcing relationship. Our research did not find any studies that focused on information security or included security as an integral component of the outsourcing decision analysis. However, there clearly seems to be a sentiment amongst vendors that lack of clarity and comprehensiveness does have an impact.

Vendor Concern 3: Dissipation of outsourcing vendor’s knowledge (C8). While this concern seems more critical for the clients, there are some significant implications for vendor firms as well. Vendors believe that because of the untoward need to comply with the whims and fancies of the clients, there is usually a dissipation of the knowledge over a period. Country Head of a large Indian outsourcing vendor noted:

The outsourcing industry has a serious problem. While we have our own business processes, we usually have to recreate or reconfigure them based on our client needs and wants. We are usually rather happy to do so. However in the process, we lose our tacit knowledge. From our perspective, it is important to ensure the protection of this knowledge. Many of our security and privacy concerns would be managed if we get a little better in knowledge management.

Perhaps Willcocks et al. [2004] are among the few researchers who have studied the importance of protection of intellectual property. Most of the emphasis has however been on protecting loss of intellectual property—largely of the client firm. Management of knowledge to protect tacit knowledge has also been studied in the literature (e.g. see [Arora 1996] and [Norman 2002]), though rarely in connection with outsourcing.

It goes without saying that poor knowledge management structures will disappoint the prospects of procuring new contracts. In comparison, the clients seem to either assume that the vendor has a sustainable structure that prevents or minimizes the loss of intellectual capital and ensures confidentiality or the client is ready to bear the risk for the perceived potential benefits. Clients expect skilled resources as a contractual requirement. As the risk for clients is minimal, they rank this in lesser importance in comparison to the vendors. Existing literature mentions, that for the better management of expectations, both clients and vendors need to understand the utility of knowledge management, implications of loss and structural requirement [Willcocks et al. 2004]. This is also reflected in the comments of one of security assurance manager:

Vendors need to minimize staff turnover and find ways to ensure staff retention and knowledge sharing. There are many methods to achieve this; such as better wages, benefits, flex time, encouragement, knowledge repositories, education opportunities, etc. They should pair veteran staff member with new staff members to improve their understanding of confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

In the literature, exchange and interplay of knowledge between partners are regarded as important for fostering organizational learning, the absence of which could cause eventual knowledge dissipation [Inkpen and Crossan 1995]. The establishment and growth of global outsourcing hinge on the extent to which clients and vendors perceive a gain from such arrangements. To realize perceived benefits, scholars emphasize on several strategies such as to improve communication and coordination processes and to encourage sharing of resources and competencies among partners (see [Chen et al. 2008]). Tacit knowledge management and ensuring the integrity of vendor business processes is a prerequisite for good and secure outsourcing.

5.2 Research Question 2—What is the extent of (in)congruence amongst the IT outsourcing clients and vendors with respect to the top ranked information security concerns?

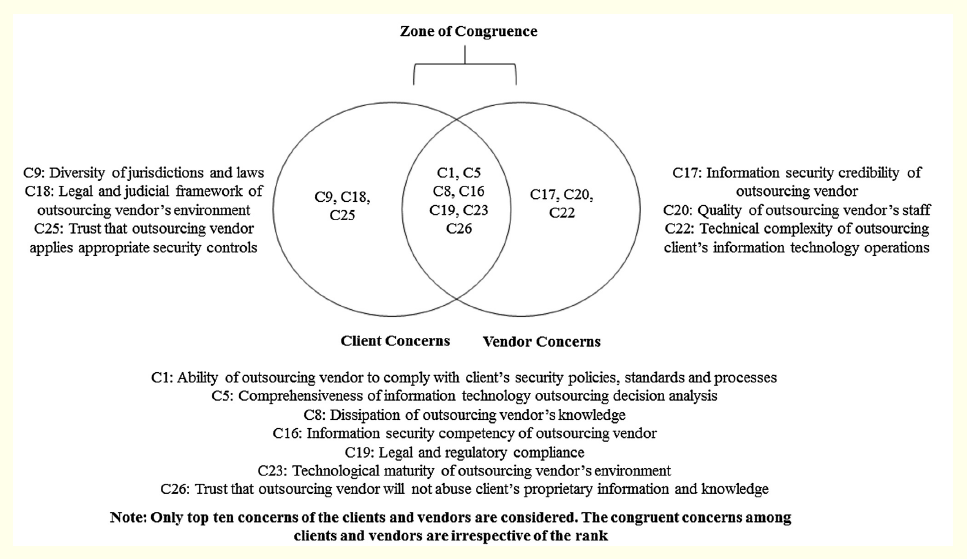

The results of our study suggest that there are zones of congruence and incongruences among clients and vendors perceptions of top information security concerns. We compared the rank ordered list of client and vendor concerns on information security in IT outsourcing relationships (see Table 4). Informed by Nakatsu and Iacovou [2009], we considered the top ten ranked concerns of each panel. Seven of the thirteen concerns fall in the zone of congruence. The results are presented in Figure 2 This means that both the client and vendor organizations agree on at least seven of the information security concerns. This does not, however, mean that they place equal importance. Client organizations had three concerns that were not regarded by the vendors in their top ten list. And vendor organizations had three concerns that do not fall within the list of top ten concerns of the client organizations.

Figure 2: Comparing Information Security Concerns of Clients and Vendors

Information Security concerns that fall in the zone of congruence are:

C1: Ability of outsourcing vendor to comply with client’s security policies, standards, and processes

C5: Comprehensiveness of information technology outsourcing decision analysis

C8: Dissipation of outsourcing vendor’s knowledge

C16: Information security competency of outsourcing vendor

C19: Legal and regulatory compliance

C23: Technological maturity of outsourcing vendor’s environment

C26: Trust that outsourcing vendor will not abuse client’s proprietary information and knowledge

Interestingly only five of the seven concerns from the zone of congruence are also listed among the top three concerns of the clients and vendors respectively. From a client perspective, ability of the outsourcing vendor to comply with client’s security policies, standards, and processes (C1) and trust that the outsourcing vendor applied appropriate security controls (C26), while being in the zone of congruence, but these are not among the top three concerns for vendors. The clients rank concerns C1 and C26 as 2 and 3 whereas the vendors rank them as 10 and 8 respectively. From a vendor perspective, comprehensiveness of information technology outsourcing decision analysis (C5), Dissipation of outsourcing vendor’s knowledge (C8), and information security competency of outsourcing vendor (C16) are in the zone of congruence concerns but do not show up among the top three concerns for the client organizations. The clients rank the concerns C5, C8, and C16 as 7, 10, and 8 whereas the vendors rank these as 2, 3, and 1 respectively.

5.3 A Framework to Ensure Information Security in IT Outsourcing

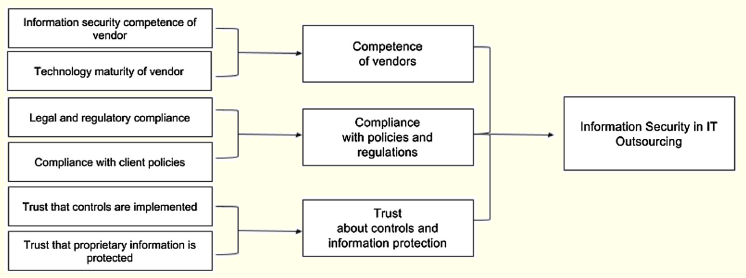

In light of our findings, we summarize our findings by proposing a framework to ensure information security in IT outsourcing (Figure 3). Based on our analysis, three major constructs that emerge are the competence of vendors; compliance with policies and regulations; and trust about controls and information protection. Together the three constructs define information security in IT outsourcing. The success of the framework is, however, dependent on the level of congruence between clients and vendors with respect to the three constructs.

Figure 3: A Framework to Ensure Information Security in IT Outsourcing

There can be several reasons for lack of agreement regarding the top concerns. First, the client and vendor organizations seem to have a different understanding of competence. As noted previously, vendors seem to believe if they have highly skilled staff, then they are competent. Clients, on the other hand, seem to suggest that the concept of competence went beyond that of good skills. Perhaps as argued by McGrath et al. [1995] and Dhillon [2008], competence in managing security is more about comprehension of the business processes and knowledge of what Weick and Roberts [1993] refers to as know-that. This is an aspect that certainly needs further investigation in future research.

Second, there seems to be a different importance placed on aspects of compliance; may it be compliance on the prevalent regulations or with the policies and procedures of the client organization. It appears to be more of a concern regarding international outsourcing because of different regulatory cultures. Clients seem to suggest that compliance is mandatory because of regulatory aspects in their respective countries. Clients also feel that the vendors need to be mindful and respectful of the confidential data. Vendors, on the other hand, recognize the regulatory and compliance aspects, but certainly do not rank them that high. As Furnell and Thomson [2009] argue, compliance depends on the degree to which clients and vendors regard information security important for IT outsourcing. Furthermore, the importance of compliance is dependent on culture, commitment, obedience, and awareness. How compliance varies across various IT outsourcing geographies is an interesting research opportunity to explore.

Third, the client organizations seem to gravitate towards the concern of trust—trust that the vendors are applying appropriate controls; trust that diverse laws and regulations are being respected. Both these concerns are critical, particularly in light of abuse of consumer information by rogue individuals and those with criminal intent. Trust is an important factor for establishing confidence among partners. Perhaps a way forward to achieve a higher degree of trust is to establish good communication and coordination mechanisms between client and vendor organizations [Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1999]. The impact of malicious or opportunistic behavior on trust and IT outsourcing presents another research opportunity.

5.4 Contributions, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

In this paper, we have systematically identified information security concerns that clients and vendors consider important in IT outsourcing relationships. To the best of our knowledge, this is perhaps one of the few studies that explicitly analyzes information security concerns in the context of IT outsourcing. The empiricaly grounded study allows us to theorize about information security in IT outsourcing. Methodologically the unique combination of an established Delphi technique with in-depth interviews allows us to develop unique insights into the subject matter. Our conceptualization of the concerns (Figure 3) does not necessarily focus on the zone of congruence or incongruence. Rather we develop insights based on the top concerns of clients and vendors and the congruent and incongruent concerns. The holistic perspective allows us to identify competence, compliance, and trust as central concepts to ensure information security in IT outsourcing.

Our study has important implications for practitioners. First, the list of 26 information security concerns identified by the experts provides IT managers with a comprehensive list that can be used to develop information security planning guidelines for IT outsourcing projects. This list has the merit of being comprehensive as it was derived by experienced panelists who are involved in global IT outsourcing projects. Second, our study provides insights about the lack of congruence between clients and vendors as one of the major risks in IT outsourcing. The findings from our study can help client and vendor managers identify and assess risks arising due to the incongruence between the client and vendor organizations, and strategize for the prevention and correction of any potential information security disruption.

The study is not without its limitations. We inherit the methodological limitations of the Delphi technique. When undertaking a Delphi study, considerable effort is required to get buy-in from the experts. It was very time consuming to identify client and vendor organizations and then get an agreement from the participants to be involved in the study. Furthermore, the follow-up interviews were conducted with the US based client and vendor

firms. As a consequence, one might question the representativeness of our experts. Our study also just focused on relationships between the US and India-based firms. It will be useful to extend the study to other contexts. While our research concludes by postulating certain relationships between competence, compliance, and trust, there is certainly a need to further

test the model empirically.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented an in-depth study of information security concerns in an IT outsourcing arrangement. We argued that while several scholars have studied the relative success and failure of IT outsourcing, the emergent security concerns have not been addressed adequately. Considering this gap in the literature, we conducted a Delphi study to identify the top information security concerns in IT outsourcing from both clients and vendors perspectives. Finally, we engaged in qualitative interviews to understand the in(congruence) between clients and vendors on the information security concerns. This in-depth analysis leads us to propose a framework to ensure information security in IT outsourcing. While we believe there should be a positive correlation amongst the proposed constructs, clearly further research is necessary in this regard.

Information security in IT outsourcing is an important aspiration for organizations to pursue. There is no doubt that many businesses thrive on getting part of their operations taken care of by a vendor. It not only makes business sense to do so, but it also allows enterprises to tap into the expertise that may reside elsewhere. Security then is simply a means to ensure a smooth running of the business. The definition of the pertinent concerns and the means to establish congruity allows us to strategically plan secure IT outsourcing.

Appendix A

Table A1: Evolution of Ranks Over Rounds: Vendors View of Concerns

Table A2: Evolution of Ranks Over Rounds: Clients View of Concerns

References

Agerfalk, P. and B. Fitzgerald (2008). Outsourcing to an unknown workforce: exploring opensourcing as a global sourcing strategy. MIS Querterly 32(2), 385–410.

Arora, A. (1996). Contracting for tacit knowledge: the provision of technical services in technology licensing contracts. Journal of Development Economics 50(2), 233–256.

Aubert, B. A., M. Patry and S. Rivard (2005). A framework for information technology outsourcing risk management. ACM SIGMIS Database 36(4), 9–28.

Aubert, B., M. Patry and S. Rivard (1998). Assessing the risk of IT outsourcing Proceedings of the Thirty-First Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 685–692.

Bachlechner, D., S. Thalmann and R. Maier (2014). Security and compliance challenges in complex it outsourcing arrangements: a multi-stakeholder perspective. Computers & Security 40, 38–59.

Barthelemy, J. (2001). The hidden costs of IT outsourcing. MIT Sloan Management Review 42(3), 60–69.

Bojanc, R. and B. Jerman-Blažic (2008). An economic modelling approach to information security risk management. International Journal of Information Management 28(5), 413–422.

Bulgurcu, B., H. Cavusoglu and I. Benbasat (2010). Information security policy compliance: an empirical study of rationality-based beliefs and information security awareness. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 523–548.

Chang, A. J. T. and Q. J. Yeh (2006). On security preparations against possible IS threats across industries. Information Management and Computer Security 14(4), 343–360.

Chen, H. H., Y. K. Kang, X. Xing, A. H. I. Lee and Y. Tong (2008). Developing new products with knowledge management methods and process development management in a network. Computers in Industry 59, 242–253.

Chowdhuri, R., G. Dhillon and M. A. Harris (2012). Understanding Information Security. Journal of Information Systems Security 8(2), 3–18.

Da Veiga, A. and J. H. P. Eloff (2010). A framework and assessment instrument for information security culture. Computers & Security 29(2), 196–207.

Dhillon, G. (2008). Organizational competence in harnessing IT: a case study. Information & Management 45(5), 297–303.

Dhillon, G., R. Syed and C. Pedron (2016). Interpreting information security culture: an organizational transformation case study. Computers & Security 56, 63–69.

Dlamini, M. T., J. H. Eloff and M. M. Eloff (2009). Information security: the moving target. Computers & Security 28(3), 189–198.

Doomun, M. R. (2008). Multi-level information system security in outsourcing domain. Business Process Management Journal 14(6), 849–857.

Dunkle, C. B. (1996). Outsourcing the catalog department: a meditation inspired by the business and library literature. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 22(1), 33–44.

Earl, M. J. (1996). The risks of outsourcing IT. Sloan Management Review 37, 26–32.

Fulford, H. and N. F. Doherty (2003). The application of information security policies in large UK-based organizations: an exploratory investigation. Information Management & Computer Security 11(3), 106–114.

Furnell, S. and K. L. Thomson (2009). From culture to disobedience: recognising the varying user acceptance of IT security. Computer Fraud & Security 2, 5–10.

Goles, T. (2001). The Impact of Client-Vendor Relationship on Outsourcing Success. University of Houston, Houston (TX).

Gonzalez, R., J. Gasco and J. Llopis (2006). Information systems outsourcing: a literature analysis? Information & Management 43(7), 821–834.

Goo, J., R. Kishore, K. Nam, H. R. Rao and Y. Song (2007). An investigation of factors that influence the duration of IT outsourcing relationships. Decision Support Systems 42(4), 2107–2125.

Haley, C. B., R. Laney, J. D. Moffett and B. Nuseibeh (2008). Security requirements engineering: a framework for representation and analysis. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 34(1), 133–153.

Handley, S. M. (2012). The perilous effects of capability loss on outsourcing management and performance. Journal of Operations Management 30(1), 152–165.

Herath, T. and H. R. Rao (2009). Encouraging information security behaviors in organizations: role of penalties, pressures and perceived effectiveness Decision Support Systems 47(2), 154–165.

Hur, J. and D. K. Noh (2011). Attribute-based access control with efficient evocation in data outsourcing systems. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 22(7), 1214–1221.

Inkpen, A. C. and M. M. Crossan (1995). Believing is seeing: joint ventures and organization learning. Journal of Management Studies 32(5), 595–618.

Jarvenpaa, S. L. and D. E. Leidner (1999). Communication and trust in global virtual teams. Organization Science 10, 791–815.

Judd, R. C. (1972). Use of Delphi methods in higher education. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 4(2), 173–186.

Kaiser, K. M. and S. Hawk (2004). Evolution of offshore software development: from outsourcing to cosourcing. MIS Quarterly Executive 3(2), 69–81.

Kern, T. and L. Willcocks (2002). Exploring relationships in information technology outsourcing: the interaction approach. European Journal of Information Systems 11(1), 3–19.

Kern, T., L. P. Willcocks and M. C. Lacity (2002). Application service provision: risk assessment and mitigation. MIS Quarterly Executive 1(2), 113–126.

Khalfan, A. M. (2004). Information security considerations in IS/IT outsourcing projects: a descriptive case study of two sectors. International Journal of Information Management 24(1), 29–42.

Lacity, M. C. and L. P. Willcocks (1998). An empirical investigation of information technology sourcing practices: lessons from experience. MIS Quarterly 22(3), 363–408.

Lacity, M. C. and R. Hirschheim (1993). The information systems outsourcing bandwagon. MIT Sloan Management Review 35, 73–86.

Lacity, M. C., S. Khan, A. Yan and L. P. Willcocks (2010). A review of the IT outsourcing empirical literature and future research directions. Journal of Information Technology 25(4), 395–433.

Lee, J. N. (2001). The impact of knowledge sharing, organizational capability and partnership quality on IS outsourcing success. Information & Management 38(5), 323–335.

Levina, N. and J. W. Ross (2003). From the vendor’s perspective: exploring the value proposition in information technology outsourcing. MIS Quarterly 27(3), 331–364.

Liu, S., J. Zhang, M. Keil and T. Chen (2010). Comparing senior executive and project manager perceptions of IT project risk: a Chinese Delphi study. Information Systems Journal 20(4), 319–355.

Liu, X., C. Xia, J. Cao, J. Gao and Z. Wei (2014). A security assessment framework and selection method for outsourcing cloud service. International Journal of Security and Its Applications 8(6), 375–388.

Loch, K. D., H. H. Carr and M. E. Warkentin (1992). Threats to information systems: today’s reality, yesterday’s understanding. MIS Quarterly 16(2), 173–186.

McGrath, R. G., I. C. MacMillan and S. Venkataraman (1995). Defining and developing competence: a strategic process paradigm. Strategic Management Journal 16(4), 251–275.

Meng, F. J., X. Y. He, S. X. Yang and P. Ji (2007). A unified framework for outsourcing governance. Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Conference on ECommerce Technology and the 4th IEEE International Conference on Enterprise Computing, E-Commerce, and E-Services, CEC/EEE, 367–374.

Miranda, S. M. and C. B. Kavan (2005). Moments of governance in IS outsourcing: conceptualizing effects of contracts on value capture and creation. Journal of Information Technology 20(3), 152–169.

Moe, N. B., D. Šmite, G. K. Hanssen and H. Barney (2014). From offshore outsourcing to insourcing and partnerships: four failed outsourcing attempts. Empirical Software Engineering 19(5), 1225–1258.

Nakatsu, R. T. and C. L. Iacovou (2009). A comparative study of important risk factors involved in offshore and domestic outsourcing of software development projects: a two-panel Delphi study. Information & Management 46(1), 57–68.

Nassimbeni, G., M. Sartor and D. Dus (2012). Security risks in service offshoring and outsourcing. Industrial Management & Data Systems 112(3-4), 405–440.

Norman, P. M. (2002). Protecting knowledge in strategic alliances: resource and relational characteristics. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 13(2), 177–202.

Okoli, C. and S. D. Pawlowski (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management 42(1), 15–29.

Osei-Bryson, K.-M. and O. K. Ngwenyama (2006). Managing risks in information systems outsourcing: an approach to analyzing outsourcing risks and structuring incentive contracts. European Journal of Operational Research 174(1), 245–264.

Pai, A. K. and S. Basu (2007). Offshore technology outsourcing: overview of management and legal issues. Business Process Management Journal 13(1), 21–46.

Posthumus, S. and R. von Solms (2004). A framework for the governance of information security. Computers & Security 23(8), 638–646.

Quélin, B. and F. Duhamel (2003). Bringing together strategic outsourcing and corporate strategy: outsourcing motives and risks. European Management Journal 21(5), 647–661.

Raghu, T. (2009). Cyber-security policies and legal frameworks governing business process and IT outsourcing arrangements. Indo-US Conference on Cyber-security Cyber-crime & Cyber Forensics.

Sabherwal, R. (1999). The role of trust in outsourced IS development projects. Communications of ACM 42(2), 80–86.

Sakthivel, S. (2007). Managing risk in offshore systems development. Communications of the ACM 50(4), 69–75.

Schmidt, R. C. (1997). Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decision Sciences 28(3), 763–774.

Schmidt, R., K. Lyytinen, M. Keil and P. Cule (2001). Identifying software project isks: an international Delphi study. Journal of Management Information Systems 17(4), 5–36.

Siponen, M. and R. Willison (2009). Information security management standards: problems and solutions. Information & Management 46(5), 267–270.

Spears, J. L. and H. Barki (2010). User participation in information systems security risk management. MIS Quarterly 34(3), 503–522.

Thomson, K. L. and R. von Solms (2006). Towards an information security competence maturity model. Computer Fraud & Security 2006(5), 11–15.

Tickle, I. (2002). Data integrity assurance in a layered security strategy, Computer Fraud & Security 2002(10), 9–13.

Tran, E. and M. Atkinson (2002). Security of personal data across national borders. Information Management & Computer Security 10(5), 237–241.

Vining, A. (1999). A conceptual framework for understanding the outsourcing decision. European Management Journal 17(6), 645–654.

Wang, W., Z. Li, R. Owens and B. Bhargava (2009). Secure and efficient access to outsourced data. Proceedings of the 2009 ACM Workshop on Cloud Computing Security, 55–66.

Weber, M. (1978). Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. University of California Press.

Wei, Y. and M. Blake (2010). Service-oriented computing and cloud computing: challenges and opportunities. IEEE Internet Computing 14(6), 72–75.

Weick, K. E. and K. H. Roberts (1993). Collective mind in organizations: heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly 38(3), 357–381.

Willcocks, L. P. and T. Kern (1998). IT outsourcing as strategic partnering: the case of the UK Inland revenue. European Journal of Information Systems 7(1), 29–45.

Willcocks, L. and M.C. Lacity (2000). Relationships in IT outsourcing: a stakholder perspective. In Zmud, R. (Ed.), Framing the Domains of IT Management, Pinnaflex Inc., Ohio, 355–384.

Willcocks, L., J. Hindle, D. Feeny and M. Lacity (2004). IT and business process outsourcing: the knowledge potential. Information Systems Management Journal 21(3), 7–15.

Williams, C. (2011). Client–vendor knowledge transfer in IS offshore outsourcing: insights from a survey of Indian software engineers. Information Systems Journal 21(4), 335–356.

Wüllenweber, K., D. Beimborn, T. Weitzel and W. König (2008). The impact of process standardization on business process outsourcing success. Information Systems Frontiers 10(2), 211–224.

Yang, D. H., S. Kim, C. Nam and J. W. Min (2007). Developing a decision model for business process outsourcing. Computers & Operations Research 34(12), 3769–3778.