Original source publication: Dhillon, G., R. Chowdhuri and F. de Sá-Soares (2013). Secure Outsourcing: An Investigation of the Fit between Clients and Providers. In Janczewski, L. J., H. B. Wolfe and S. Shenoi (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th IFIP TC 11 International Conference—Security and Privacy Protection in Information Processing Systems—SEC 2013, 405–419. Auckland (New Zeland). Springer 2013 IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, ISBN: 978-3-642-39217-7.

The final publication is available here.

Secure Outsourcing: An Investigation of the Fit between Clients and Providers

a Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, USA

b Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Abstract

In this paper we present an analysis of top security issues related to IT outsourcing. Identification of top issues is important since there is a limited understanding of security in outsourcing relationships. Such an analysis will help decision makers in appropriate strategic planning for secure outsourcing. Our analysis is conducted through a two-phase approach. First, a Delphi study is undertaken. Second, an intensive study of results from phase one is conducted through in depth interviews with key decision makers.

Keywords: Secure Outsourcing; Congruence; Client Vendor Fit; Delphi Study

1. Introduction

Information security is a significant sticking point in establishing a relationship between Information Technology (IT) outsourcing vendors and clients. While statistics related to outsourcing risks and failures are abound, there has been a limited emphasis on understanding information security related reasons for outsourcing problems. We believe that many of the problems stem from a lack of fit between what IT outsourcing vendors consider to be the key success factors and what outsourcing clients perceive to be critical for the success of the relationship. It is important to undertake such an investigation because of two primary reasons. First, majority of IT outsourcing projects fail because of a lack of appreciation as to what matters to the clients and the vendors [Barthélemy 2001; Kaiser and Hawk 2004]. Second, several IT outsourcing projects fall victim to security breaches because of a range of issues—broken processes, failure to appreciate client requirements [Earl 1996], among others. If strategic alignment between IT outsourcing vendors and clients were maintained many of the security challenges could be overcome.

A first step in ensuring a strategic fit with respect to information security is to identify as to what is important for the vendors and the clients respectively. In this paper we undertake an extensive Delphi study to identify information security issues related to both the vendors and the clients. This is followed up by an intensive analysis of the issues through in depth interviews with several client and vendor firms.

2. Informing Literature

In recent years there have been several security breaches where privacy and confidentiality of data has been compromised largely because there was a lack of control over the remote sites. In 2011 an Irish hospital reported breach of patient information related to transcription services in the Philippines. In another US Government Accounting office survey it was reported that at least 40 percent of federal contractors and state Medicare agencies experienced a privacy breach (see GAO-06-676)1. While it is mandatory for the contractor to report breaches, there is limited oversight. Given the challenges many corporations have begun implementing a range of technical controls to ensure security of their own infrastructures rather than rely on the vendors.

In addressing the security challenges in outsourcing relationships or for that matter any kind of a risk, management of client-vendor relationship has been argued as important. Dibbern et al. [2004] provide references to the literature that mainly discuss the phases of relationship between client and vendor and the issues involved in each of the phases. For example, Relationship Structuring involves issues deemed important when the outsourcing contract is being prepared, Relationship Building discuss issues that contribute to strengthening the relationship between client and vendor, and Relationship Management involve issues that are relevant to drive the relationship in the right direction. Lacity et al. [2010] list 25 independent variables that can impact the relationship between outsourcing client and vendor. The most cited factors include effective knowledge sharing, cultural distance, trust, prior relationship status, and communication.

Studies related to secure outsourcing have been few and far between. In majority of the cases the emphasis has been on contractual aspects of the relationship between the client and the vendor. And many researchers have made calls for clarity in contracts as well as selective outsourcing [Lacity and Willcocks 1998]. Managing the IT function as a value center [Venkatraman 1997] has also been proposed as a way for ensuring success of outsourcing arrangements. There is no doubt that prior research has made significant contribution to the manner in which advantages can be achieved from outsourcing relationships, however there has been limited contribution with respect to management of security and privacy.

Kern et al. [2002] considered security of internet as one of the technological risks. Khalfan [2004] reported the results of a study in which security issues related to data confidentiality, integrity and availability emerged as the topmost concerns in an outsourcing arrangement. While few surveys report computer networks, regulations and personnel as the highest security threats to organizations [Chang and Yeh 2006] others recognize that not only technical but also non-technical threats can be detrimental to an engagement [Chang and Yeh 2006; Dlamini et al. 2009; Pia and Basu 2007]. However, most of the work cited under the domain of IS outsourcing risks is generic and has a very limited focus on security [Earl 1996; Sakthivel 2007]. Several researchers have provided the frameworks to identify the organizational assets at risk and to use financial metrics to determine priority of assets that need protection [Bojanc and Jerman-Blazic 2008; Osei-Bryson and Ngwenyama 2006]. Colwill and Gray [2007] provide a list of security threats prevalent in an outsourcing or offshore environment and review risk management models. The political, cultural and legal differences between supplier and provider environment are supposed to make the environment less favorable for operators. Doomun [2008] proposed a multi-layer security model to mitigate the security risks in outsourcing domains. Eleven steps in an outsourcing arrangement are divided across three layers of security: identification, monitoring and improvement, and measurement. And each layer addresses both technical and nontechnical requirements of security.

Wei and Blake [2010] provided a comprehensive list of information security risk factors involved in an outsourcing IT projects and also provide safeguards for IT offshore outsourcing. Mostly, the risks identified in the study were borrowed from previous literature. More recently, Nassimbeni et al. [2012] categorized the security risks into three phases: strategic planning, supplier selection and contracting, implementation and monitoring. However, the set of issues have been mainly borrowed from existing literature. Some of the researchers have also classified the risks as external and internal threats to an organization and human and non-human risks. Nontechnical concerns such as employees, regulations, trust have emerged as more severe than the technological risks [Loch et al. 1992; Posthumus and von Solms 2004; Tickle 2002; Tran and Atkinson 2002]. As such few studies are concerned with a specific type of security concern such as policies [Fulford and Doherty 2003].

While the prevalent IT outsourcing research has certainly helped in better understanding the client-vendor relationships, an aspect that has largely remained unexplored is that of organizational fit. In the IT strategy domain organization fit has been explored in terms of alignment between IT strategy and the business strategy [Henderson and Venkatraman 1993]. In the strategy literature it has been studied in terms of the fit between an organization’s structure and its strategy. Even though [Livari 1992] made a call for understanding organizational fit of information systems with the context, little progress has been made to date.

In the context of IT outsourcing the notion of the fit between a client and the vendor has also not been well studied. Nightingale and Toulouse [1977] have suggested that fit can be understood through the elements of congruence theory, which explains the interactions among organizational environment, values, structure, process and reaction-adjustment. Based on congruence theory, an outsourcing environment thus can be defined as the existence of any condition such as culture, regulations, provider/supplier capabilities, security, and competence that can determine the success of an outsourcing arrangement. Organizational values determine the acceptable and unacceptable behavior. In this respect factors such as trust, transparency and ethics fall under the value system of an organization. Structure of an outsourcing arrangement defines the factors such as reporting hierarchy, ownership and processes for communication. Additionally reaction-adjustments are required, which entail the feedback and outcomes of an engagement and the related modifying strategy in response to the reactions of clients for a better strategic fit and alliance between outsourcing clients and vendors.

Clearly the existing literature on identification and mitigation of security risks is rich. The security risks at technical, human and regulatory levels are well identified; many of the studies highlight that non-technical risks are more severe than the technical ones. However, the literature is short of two perspectives: First, gap analysis of how outsourcing clients and outsourcing vendors perceive the security risks does not exist. Second, the existing literature does not discuss much about the congruence among different concepts in an outsourcing arrangement, particularly in the security domain. Hence to determine a fit between suppliers and clients, we need to understand as to what security issues are important to the clients and the vendors and then to establish a basis for their congruence.

3. Research Methodology

Given that the purpose of this study was to identify security concerns amongst outsourcing clients and vendors, a two-phased approach was adopted. In the first instance a Delphi study was undertaken. This helped us in identifying the major security issues as perceived by the clients and the vendors. In the second phase an in depth analysis of clients and vendors was undertaken. This helped us in understanding the reasons for significant differences in their perceptions.

3.1 Phase 1—A Delphi study

To ensure a reliable and validated list of issues that are of concern to the organizations, both from client and provider perspective, a process to inquire and seek the divergent opinions of different experts is provisioned in the first phase. A ranking method based on Schmidt’s Delphi methodology, designed to elicit the opinions of panel of experts through controlled inquiry and feedback, is employed [Schmidt 1997]. Delphi study allowed factors to converge to the ones that really are important in outsourcing information technology security.

Panel Demographics

To account for varying experiences, and role of experts, both outsourcing vendors or providers and outsourcing clients or suppliers were chosen as the target panelists. A total of 11 panelists were drawn from the pool of 21 prospective participants. We identified senior IS executives from major corporations and asked them to identify the most useful and experienced people to participate in the survey. The participants were divided into two groups—Outsourcing Providers (5) and Outsourcing Suppliers (6). The panelists had impressive and varied experiences in IT outsourcing and management. The number of panelists suffices the requirement of eliciting diverse opinions and prevents the panelists from being intimidated with the volume of feedback. Moreover, the comparative size of the two panels is irrelevant since it doesn’t have any impact on the response analysis. For detecting statistically significant results, the group size is dependent on the group dynamics rather than the number of participants; therefore, 10 to 11 experts is a good sample size [Okoli and Pawlowski 2004].

Data Collection

The data collection phase is informed by Schmidt’s [1997] method, which divides the study into three major phases. The first round - brainstorming or blank sheet round—was conducted to elicit as many issues as possible from each panelist. Each participant was asked to provide at least 6 issues along with a short description. The authors collated the issues by removing duplicates. The combined list was sent to panelists explaining why certain items were removed and further asked the panelists for their opinion on the integrity and uniformity of the list. In the second round we asked each panelist to pare down the list to most important issues. A total of 26 issues were identified which were sent to panelists for further evaluation, addition, deletions and/or verification. This is to ensure that a common set of issues is provided for the panelist to rank in subsequent rounds. Ranking of the final 26 issues was done in phase 3. During this phase each panelist was required to rank the issues in order of importance with 1 being the most important security issue and 26 being the least important security issue in outsourcing. The panelists were restricted to have the ties between two or more issues.

At the end of every ranking round, five important pieces of feedback were sent to panelists: (1) mean rank for each issue; (2) level of agreement in terms of Kendall’s W; (3) Spearman correlation rho, (4) P-value; (5) relevant comments by the panelists.

Data Analysis

The analysis of the results was performed in two parts: First, an analysis of aggregated Delphi study treats all respondents as a global panel and thus presents the unified ranking results. Second, an analysis of partitioned Delphi study presents the ranking results based on respondents group, i.e. outsourcing providers and outsourcing clients.

3.2 Phase 2—Probing for Congruence using Qualitative technique

The second round of data collection was based on two workshops with representatives from Fortune 500 companies. There were 11 individuals with an average of 8 years of work experience who participated in these workshops. The workshops were conducted from May 2012 to July 2012. In the first workshop, each participant was required to answer three questions for all 26 issues. Suitable probes were added following each question. This helped in developing a rich insight.

What do you think about the issue?

Why do you think it is important for outsourcing provider?

Why do you think it is important for outsourcing client?

The second workshop was concentrated to achieve congruence between outsourcing suppliers and outsourcing providers. Different ranks assigned by clients and vendors to particular issues were highlighted. The participants were asked answer two questions so as to elicit their opinions on the gaps identified in the ranking sought by clients and providers for the issues.

Explain what do you think is the reason for assigning different ranks by outsourcing clients and outsourcing providers?

Explain what can be done to resolve the difference in order to seek a common ground of understanding between clients and providers?

4. Findings from the Delphi Study

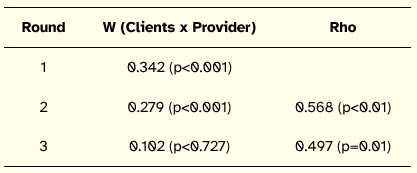

For phase one, the results were analyzed from a global or aggregated view and partitioned or client vs. vendor view. The global panel reached a weak consensus by third ranking round (see Table 1).

Table 1: Global Consensus

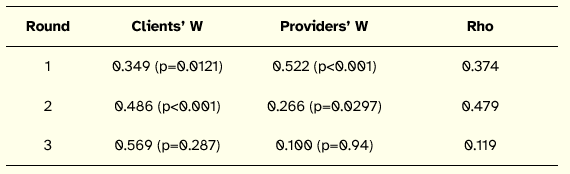

On the other hand, by the third ranking round, Clients had fair agreement whereas vendors had very weak agreement. Moreover, a weak positive correlation exists between round 2 and round 3 in global ranking as well as between clients and providers by round 3 (see Table 2).

Table 2: Client and Vendor Consensus

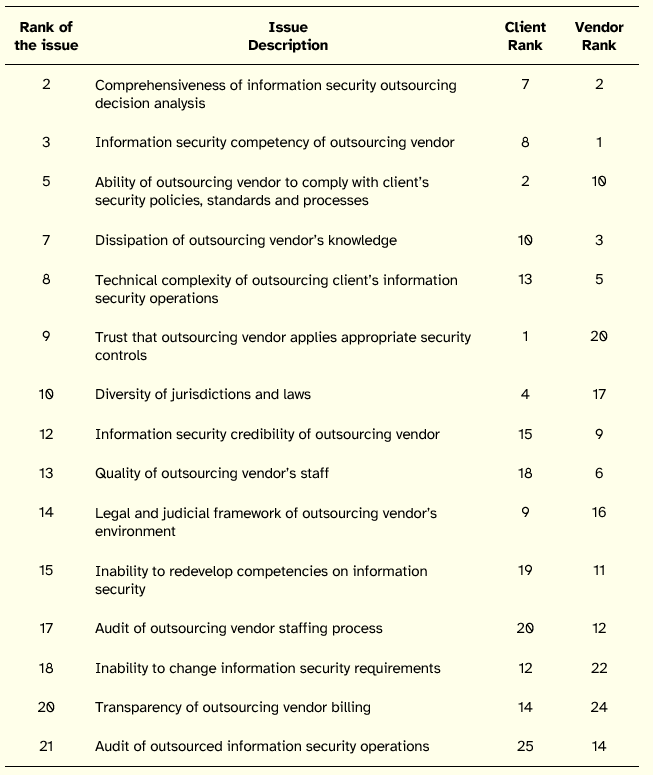

The weak consensus in global ranking clearly suggests that outsourcing clients and outsourcing vendors have conflict of interest. Moreover, the weak consensus within vendors indicates that not all vendors perceive the importance of security at same level. And finally the difference between ranks assigned to each issue by clients and vendors further highlight the conflict of interest between two. Table 3 presents a comparison of the ranks from client and vendor perspectives and shows a significant divide between the two groups. The issues are sorted compositely; however, given the significant difference for few of the issues, the composite rank is irrelevant. For this paper we assume a difference of more than three between the ranks sought by client and vendors as significant. Thereby, a total of 16 issues out of 26 show significant difference between the rankings of two groups.

Table 3: Comparison of Client and Vendor ranks (only significant issue are presented)

5. Reviewing Congruence amongst Issues

It is interesting to note that there is a significant difference in the client and vendor perspectives of the top secure outsourcing issues. In this section we explore these issues further to develop a better understanding of secure outsourcing. In terms of managing security of outsourcing it makes sense to develop a fit between what the clients and the vendors consider important.

Two issues that seem to be of significant concern for both the client and the vendors is of diversity of laws and the legal and judicial framework of the vendor’s environment. Both these concerns are indeed significant. Our discussions with a CIO of a major bank in the US, which has outsourced significant amount of IT services to India, suggest jurisdictional issues to be a major concern. The CIO noted:

I can say with absolute certainty that we have our outsourcing experience has been very positive. We found significantly high level of competence in our vendor. However there are constant challenges of dealing with the regulatory environment. Laws in the US are rather strict in terms of disclosure and we feel that to be an impediment to getting our work done.

The literature has reported similar concerns, albeit with respect to mainstream outsourcing issues rather than security. Pai and Basu [2007] have argued that there are issues of conformance and contractual violations, which can have a detrimental impact on outsourcing relationships. It is interesting to note though that both issues 10 and 14 rank higher amongst the clients than the vendors. It seems that regulatory compliance and prevalence of a judicial framework is more of a concern to the outsourcing clients than the vendors. Another IT manager in our study commented:

Increased transparency regarding the laws governing the vendor may mitigate the risk for the client. However, the burden is on the vendor to reassure the client that the risk is minimal. Therefore the vendor should be supplying as much information to reassure the client that they are working under the same legal context and that their legal agreements are mutually beneficial.

In the literature several calls have been made that suggest clarity of legal and regulatory frameworks (e.g. [Raghu 2009]). Beyond clarity however there is a need to work on aligning the legal and regulatory frameworks at a national level. Country specific institutions shall play a critical role ensuring such alignment (e.g. NASSCOM in India). To better mitigate the risks and to ensure that the interest of both parties are secured, there needs to be increased transparency in legal structure. The burden lies on the supplier though. Therefore the vendor should be making available as much information to reassure the client that they are working under the same legal context and that their legal agreements are mutually beneficial. As a principle we therefore propose:

Principle 1—Reducing the diversity of laws and ensuring congruence of legislative controls ensure security in outsourcing.

Another issue, dissipation of outsourcing vendors knowledge, emerged to be significant. While this issue seems more critical for the vendors, there are some significant implications for the client firms as well. Vendors believe that because of the untoward need to comply with the whims and fancies for the clients, there is usually a dissipation of the knowledge over a period of time. One of the members of our intensive study was the country head for a large Indian outsourcing vendor. When asked to comment of this issue, he said:

The outsourcing industry has a serious problem. While we have our own business processes, we usually have to recreate or reconfigure them based on our client needs and wants. We are usually rather happy to do so. However in the process we lose our tacit knowledge. From our perspective it is important to ensure protection of this knowledge. Many of our security and privacy concerns would be managed if we got a little better in knowledge management.

Perhaps Willcocks et al. [2004] are among the few researchers who have studied the importance of protection of intellectual property. Most of the emphasis has however been on protecting loss of intellectual property–largely of the client firm. Management of knowledge to protect tacit knowledge has also been studied in the literature (e.g. see [Arora 1996], [Norman 2002]), though rarely in connection with outsourcing.

It goes without saying that poor knowledge management structures will disappoint the prospects of procuring of new contracts. In comparison, the clients seem to either assume that the supplier has a sustainable structure that prevents or minimizes the loss of intellectual capital and ensures confidentiality or client is ready to bear the risk for the perceived potential benefits. Clients expect skilled resources as a contract requirement. As the risk for clients is minimal, therefore they rank this in less importance in comparison to the vendor. As Willcocks et al. mention that for the better management of expectations, both clients and suppliers need to understand the utility of knowledge management, implications of loss and the structural requirement. This is also reflected in the comments of one of security assurance manager:

Suppliers need to minimize staff turnover and find ways to ensure staff retention and knowledge sharing. There are many methods to achieve this such as better wages, benefits, flex time, encouragement, knowledge repositories, education opportunities, etc. They should pair veteran staff member with new staff members to improve their understanding of confidentiality, integrity and availability.

As a principle we therefore propose:

Principle 2—Tacit knowledge management and ensuring the integrity of vendor business processes is a pre-requisite for good and secure outsourcing.

Our research also found information security competency of outsourcing vendor as a significant issue. Many scholars have commented on the importance of vendor competence [Goles 2001; Levina and Ross 2003; Willcocks and Lacity 2000]. Levina and Ross [2003] in particular have argued that value based outsourcing outcome should be generated and transferred from the vendor to the client. However, as is indicative from our study, clients and vendors differ in their opinions on what is most important when selecting and promoting outsourcing security services. While, vendors often believe that proving their competency through a large list of certifications, awards, and large clientele is important to have to prove their competency, the client’s perspective is geared towards the application and utilization of supplier competency. One of the IT managers from a bank noted:

The vendor is expected to be competent in their area of expertise, so the client needs to make clear to the vendor that a basic expectation should not be at the top of their list as there are more important factors that will be used to differentiate the vendors from one another.

As is rightly pointed out by the IT Manager, the issue with managing competence is not to present a baseline of what the vendor knows (i.e. the skill set), but a demonstration of the know-that (see [Dhillon 2008]). Assessment of competence is outwardly driven and hence a presentation of some sort of maturity in security management is essential (e.g. ISO 21827). As a principle we propose:

Principle 3—A competence in ensuring secure outsourcing is to develop an ability to define individual know-how and know-that.

It is great that a company can claim they are competent in providing outsourced information security but it means nothing to the client unless the client perceives their specific policies as being effectively applied by the provider.

To eliminate the gap, processes and policies need to be comprehensive enough and the contracts need to emphasize the implications of non-compliance. For the sake of continued alliance, the responsibility lies more on vendor to ensure process compliance and governance. Another manager from a client organization commented:

Clients are usually outsourcing to relieve their workload and performing a comprehensive analysis is viewed as adding to the existing workload they are trying to relieve. The more a potential supplier is willing to be an active partner and point out the pros and cons of their own proposals as well as the others, the smaller the gap will be.

As a principle, we propose:

Principle 4—Establishing congruence between client and vendor security policies ensures protection of information resources and a good working arrangement between the client and the vendor.

If leveraging the core competency of suppliers is the main motive to outsource security operations, the lower ranking by clients for the issue—audit of outsourced information security operations—is justified. Clients expect competency of the outsourcing vendor to be in place. However, clients also seem to lack consensus on the need for continued monitoring and governance procedures. Auditing is one of the means for the client to verify whether the vendor is adhering to the security policies. Vendors by virtue of providing a higher rank in comparison to clients, appear to be aware of the importance of proving continued compliance with agreements. Providing audited or auditable information relating to the clients data and processes is a must for establishing trust. Much of the research in IS outsourcing has focused on different dimensions of governance procedures including contracts, and non-contractual mechanisms of trust building [Miranda and Kavan 2005]. Auditing and third party assurance, which leads to increased trust (see issues 4 and 9 in our study), typically do not seem to be touched upon.

A related issue (and also connected to principle 4 above) is that of a competence audit. Any audit of vendor operations must include several aspects including—overall competence in information security (issue 15 in our study) and quality of vendor staff (issue 13). Our research subjects reported several instances where there was a general loss of competence over a period of time. This usually occurs when either the vendor organization gets too entrenched with one client and hence overlooking the needs of the other or when internal processes are patched and reconfigured in a reactive manner to ensure compliance with the expectations of a given client (refer to issue 5 in our study). One Chief Information Security Officer from a healthcare organizations commented:

There seems to be this half-life of a security competence. I have seen that after a contract has been signed, there is a somewhat exponential decay in quality.

In the literature there is some mention of such decay in quality, although not directly in relation to outsourcing (e.g. see [Sterman et al. 1997]). Sterman et al [1997] found that many of the quality improvement initiatives can interact with prevailing systems and routines to undercut commitment to continuous improvement. While our research does not suggest this to be the case in terms of secure outsourcing, the differences in opinion between the clients and the vendors seem indicative. As a principle we therefore propose:

Principle 5—An internal audit of both the client and vendor operations is critical to understand current weaknesses and potential problems there might be with respect to information security structures, procedures and capabilities.

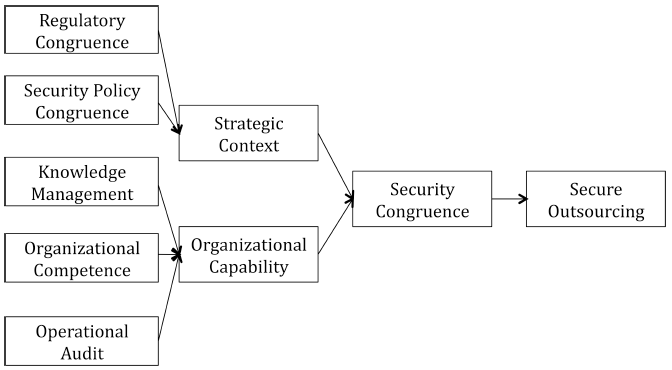

Based on our research, two major constructs seem to emerge–strategic context of secure outsourcing and organizational capability in outsourcing (Figure 1). The strategic context is defined by legal/regulatory congruence and security policy alignment. In our context organizational capability is a function of knowledge management, competence and audit. Combined together, our constructs define security congruence. The level of congruence however can only be assessed through outcome measures (secure outsourcing). Such outcome measures could include reduced incidents of security breaches, high ranks from external vetting organizations etc.

Figure 1: Modeling Security Congruence

In the context of security of information resources, the need to develop a fit between outsourcing partners seems to be appropriate. Significant variations in the rankings on part of vendor raise some doubts: if they value the sensitivity of client data; if they ensure adequate protection of the assets; if the vendor is aware of the vulnerabilities in their processes. All these issues would also raise concern about the attitude of the client, particularly in relation to shunning responsibilities. This can indeed be a classic example of strife between factions of affordability and availability.

In order to achieve the congruence between clients and vendors, the discussion so far leads to the emergence of one main theme—managing expectations. In the purview of congruence theory this requires elimination of gaps between the two parties and eventually align the two organizations (in our case around strategy and capability as per figure 1). Figure 1 provides a conceptual design of such an aligned organization. For better management of expectations, the supplier and vendor organizations need to communicate and coordinate their respective operations.

6. Conclusion

In this paper we have presented an in depth study of secure outsourcing. We argued that while several scholars have studied the relative success and failure of IT outsourcing, the emergent security issues have not been addressed adequately. Considering this gap in the literature we conducted a Delphi study to identify the top security outsourcing issues from both the clients and the vendors perspectives. Finally we engaged in an intensive study to understand why there was a significant difference in ranking of the issues by the vendors and the clients. This in depth understanding lead us to propose five principles that organizations should adhere to in order to ensure security of outsourcing relations. A model for security congruence is also proposed. While we believe there to be a positive correlation amongst the proposed constructs, clearly further research is necessary in this regard.

Secure outsourcing is an important aspiration for organizations to pursue. There is no doubt that many businesses thrive on getting part of their operations taken care of by a vendor. It not only makes business sense to do so, but it also allows enterprises to tap into the expertise that may reside elsewhere. Security then is simply a means to ensure smooth running of the business. And definition of the pertinent issues allows us to strategically plan secure outsourcing relationships.

References

Arora, A. (1996). Contracting for tacit knowledge: the provision of technical services in technology licensing contracts. Journal of Development Economics 50(2), 233–256.

Barthelemy, J. (2001). The hidden costs of IT outsourcing. MIT Sloan Management Review 42(3), 60–69.

Beth, T., M. Borcherding and B. Klein (1994). Valuation of trust in open networks. Computer Security—ESORICS 94, 1–18.

Bojanc, R. and B. Jerman-Blažič (2008). An economic modelling approach to information security risk management. International Journal of Information Management 28(5), 413–422

Chang, A. J. T.a nd Q. J. Yeh (2006). On security preparations against possible IS threats across industries. Information Management & Computer Security 14(4), 343–360.

Colwill, C. and A. Gray (2007). Creating an effective security risk model for outsourcing decisions. BT Technology Journal 25(1), 79–87.

Dhillon, G. (2008). Organizational competence in harnessing IT: a case study. Information & Management 45(5), 297–303.

Dhillon, G. and G. Torkzadeh (2006). Value‐focused assessment of information system security in organizations. Information Systems Journal 16(3), 293–314.

Dibbern, J., T. Goles, R. Hirschheim and B. Jayatilaka (2004). Information systems outsourcing: a survey and analysis of the literature. ACM SIGMIS Database 35(4), 6–102.

Dlamini, M. T., J. H. Eloff and M. M. Eloff (2009). Information security: The moving target. Computers & Security 28(3), 189–198.

Doomun, M. R. (2008). Multi-level information system security in outsourcing domain. Business Process Management Journal 14(6), 849–857.

Earl, M. J. (1996). The risks of outsourcing IT. Sloan Management Review 37, 26–32.

Fulford, H. and N. F. Doherty (2003). The application of information security policies in large UK-based organizations: an exploratory investigation. Information Management & Computer Security 11(3), 106–114.

Goles, T. (2001). The Impact of Client-Vendor Relationship on Outsourcing Success. University of Houston, Houston, TX.

Henderson, J. C. and N. Venkatraman (1993). Strategic alignment: leveraging information technology for transforming organisations. IBM Systems Journal 32(1), 4–16.

Kaiser, K. M. and S. Hawk (2004). Evolution of offshore software development: From outsourcing to cosourcing. MIS Quarterly Executive 3(2), 69–81.

Kern, T., L. P. Willcocks and M. C. Lacity (2002). Application service provision: Risk assessment and mitigation. MIS Quarterly Executive 1(2), 113–126.

Khalfan, A. M. (2004). Information security considerations in IS/IT outsourcing projects: a descriptive case study of two sectors. International Journal of Information Management 24(1), 29–42.

Lacity, M. C. and L. P. Willcocks (1998). An Empirical Investigation of Information Technology Sourcing Practices: Lessons from Experience. MIS Quarterly 22(3), 363–408.

Lacity, M. C., S. Khan, A. Yan and L. P. Willcocks (2010). A review of the IT outsourcing empirical literature and future research directions. Journal of Information Technology 25(4), 395–433.

Levina, N. and J. W. Ross (2003). From the vendor’s perspective: exploring the value proposition in information technology outsourcing. MIS Quarterly 27(3), 331–364.

Livari, J. (1992). The organizational fit of information systems. Information Systems Journal 2(1), 3–29.

Loch, K. D., H. H. Carr and M. E. Warkentin (1992). Threats to information systems: today’s reality, yesterday’s understanding. MIS Quarterly 16(2), 173–186.

Miranda, S. M. and C. B. Kavan (2005). Moments of governance in IS outsourcing: conceptualizing effects of contracts on value capture and creation. Journal of Information Technology 20(3), 152–169.

Nassimbeni, G., M. Sartor and D. Dus (2012). Security risks in service offshoring and outsourcing. Industrial Management & Data Systems 112(3), 4.

Nightingale, D. V. and J. M. Toulouse (1977). Toward a multilevel congruence theory of organization. Administrative Science Quarterly 22(2), 264–280.

Norman, P. M. (2002). Protecting knowledge in strategic alliances: Resource and relational characteristics. The Journal of High Technology Management Research 13(2), 177–202.

Okoli, C. and S. D. Pawlowski (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management 42(1), 15–29.

Osei-Bryson, K.-M. and O. K. Ngwenyama (2006). Managing risks in information systems outsourcing: an approach to analyzing outsourcing risks and structuring incentive contracts. European Journal of Operational Research 174 (1), 245–264

Pai, A. K. and S. Basu (2007). Offshore technology outsourcing: overview of management and legal issues. Business Process Management Journal 13(1), 21–46.

Posthumus, S. and R. von Solms (2004). A framework for the governance of information security. Computers & Security 23(8), 638–646.

Raghu, T. (2009). Cyber-security policies and legal frameworks governing Business Process and IT Outsourcing arrangements. Indo-US Conference on Cybersecurity, Cyber-crime & Cyber Forensics.

Sakthivel, S. (2007). Managing risk in offshore systems development. Communications of the ACM 50(4), 69–75

Schmidt, R. (1997). Managing Delphi surveys using nonparametric statistical techniques. Decision Sciences 28(3), 763–774.

Sirdeshmukh, D., J. Singh and B. Sabol (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. The Journal of Marketing 66(1), 15–37.

Sterman, J. D., N. P. Repenning and F. Kofman (1997). Unanticipated side effects of successful quality programs: Exploring a paradox of organizational improvement. Management Science 43(4), 503–521.

Tickle, I. (2002). Data integrity assurance in a layered security strategy. Computer Fraud & Security 2002(10), 9–13.

Tran, E. and M. Atkinson (2002). Security of personal data across national borders. Information Management & Computer Security 10(5), 237–241.

Venkatraman, N. (1997). Beyond outsourcing: managing IT resources as a value center. Sloan Management Review 38(3), 51–64.

Wei, Y. and M. Blake (2010). Service-oriented computing and cloud computing: Challenges and opportunities. Internet Computing 14(6), 72–75.

Willcocks, L. and M. C. Lacity (2000). Relationships in IT Outsourcing: A Stakholder Perspective. In Zmud, R. (Ed.), Framing the Domains of IT Management, 355–384. Pinnaflex Inc., Ohio.

Willcocks, L., J. Hindle, D. Feeny and M. Lacity (2004). IT and business process outsourcing: The knowledge potential. Information Systems Management 21(3), 7–15.

Wüllenweber, K., D. Beimborn, T. Weitzel and W. König (2008). The impact of process standardization on business process outsourcing success. Information Systems Frontiers 10(2), 211–224.

Endnotes

1 http://www.gao.gov/assets/260/251282.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2013