Original source publication: Carvalho, J. Á. e F. de Sá-Soares (2022). Sistemas de Informação—Uma Reflexão sobre a Natureza da Área Científica de Sistemas de Informação: Da Investigação Científica à Prática Profissional. In Ramos, I., R. D. Sousa e R. Quaresma (Eds.), Sistemas de Informação—Diagnósticos e Prospetivas, pp. 21–44, Lisboa: Edições Sílabo.

The final publication is available here.

Information Systems—A Reflection on the Nature of the Scientific Field of Information Systems: From Scientific Research to Professional Practice

University of Minho, Portugal

Note: Chapter translated from Portuguese to English.

1. Introduction

We can consider that the scientific field of information systems (IS) emerged in the 1960s with the realization that the use of computers (electronic, digital) to process information in organizations/enterprises constitutes itself a distinct field of academic interest. Being a young scientific field, it is not surprising that its nature and legitimacy might be, from time to time, questioned or, sometimes, not at all understood. Indeed, its inherent interdisciplinarity makes its scope diffuse and allows the existence of different perspectives, anchored in each one of the multiple fields that contribute to it.

This article should be understood as an essay in which the nature of the scientific field of IS is presented and justified, revealing the position of its authors on the subject. Therefore, it does not correspond to a report of empirical research. It will present and debate the objects of interest of the scientific field, the professional profiles to which it is associated and the methods of scientific inquiry it uses.

The point of mentioning professional profiles associated with the IS field is significant. On the one hand, the IS field has been associated with vocational training concerns since its inception—the preparation of professionals that, in enterprises, make it easier to obtain and use information technology (IT)—computers and related technologies—to achieve some kind of business benefit. On the other hand, it is easy to recognize that a significant part of the body of knowledge that constitutes the field has a clear orientation towards actions that seek the success of entities that use IT in order to, somehow, process the information they are dealing with.

2. The Emergence of the Scientific Field of Information Systems

The name used—management information systems (MIS)—reflects the initial focus of the field: the use of computers to produce information capable of improving decision-making and increase managers’ control of enterprises. It could be said that this focus replaces a previous concern centered on efficient information processing, associated with designations such as automatic data processing or electronic data processing. However, as the scope of computers application expanded, new areas of interest have emerged [Bacon and Fitzgerald 1996]. Decision Support Systems, Strategic Information Systems, End-User Computing, Information Resource Management and Information Systems Management are examples of designations that have been emerging in the subsequent decades and that reflect new concerns about the use of computers in enterprises. At the same time, in reaction to the repercussions that the operation of computer and platform applications have been having in contexts other than that of enterprises, the IS field has been incorporating other concerns and interests, such as e-democracy, information society, smart cities, cyber warfare, etc.

3. Characterization of the IS Field

3.1 Objects of Interest and Relevant Phenomena

What we now call IS is therefore a scientific field that involves any manifestations of IT (computers and other concomitant technologies of automatic processing of information, either in terms of applications and infrastructures), which includes different types of information objects, and which encompasses a diverse range of situations and contexts where information technologies are used in information processing.

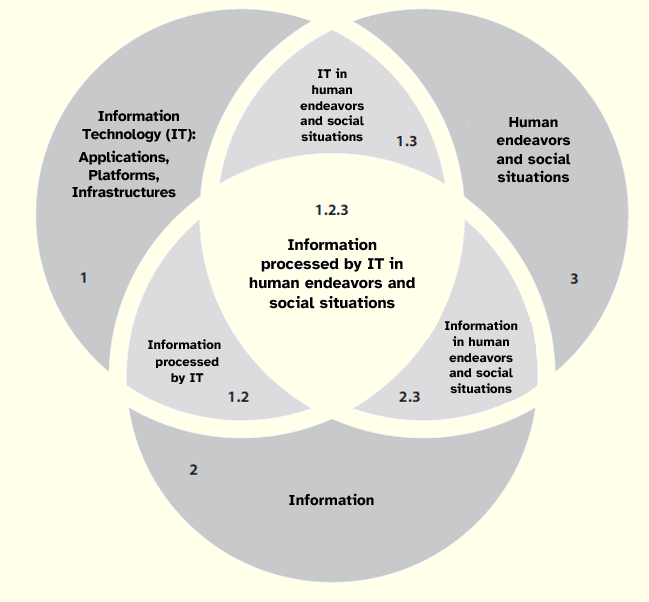

IS thus involves the combination of three areas of interest: IT, information, and the human endeavors and social situations in which IT operates. Figure 1 seeks to illustrate that the combination of these three areas leads to the emergence of a space, of an interdisciplinary nature, where IS objects of interest are included—area marked 1.2.3 in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The cientific field of Information Systems (IS) as a space where three areas intersect (interdisciplinary) whose objects of interest are information technologies, information, and human endeavors and social situations

Figure 1 also shows the possibility of intersecting spaces, which involve only two of those areas (1.2, 1.3 and 2.3). These are hinge spaces that are both recognized as IS and also as part of any of the other areas involved. The Figure also shows the spaces where each of those areas is considered in isolation, without intersecting with the others, i.e., without the elements of the other areas taking relevance. Consequently, these are spaces that are already outside the IS field.

The central area is particularly interesting and challenging. From the point of view of research involves addressing a combination of objects of interest—at different levels of analysis—which brings with it the need to resort to a wide variety of research methods. And, in the dimension of professional practice, implies the use of approaches that, because they include human and social aspects, as well as technical artifacts, are sometimes referred to as socio-technical approaches.

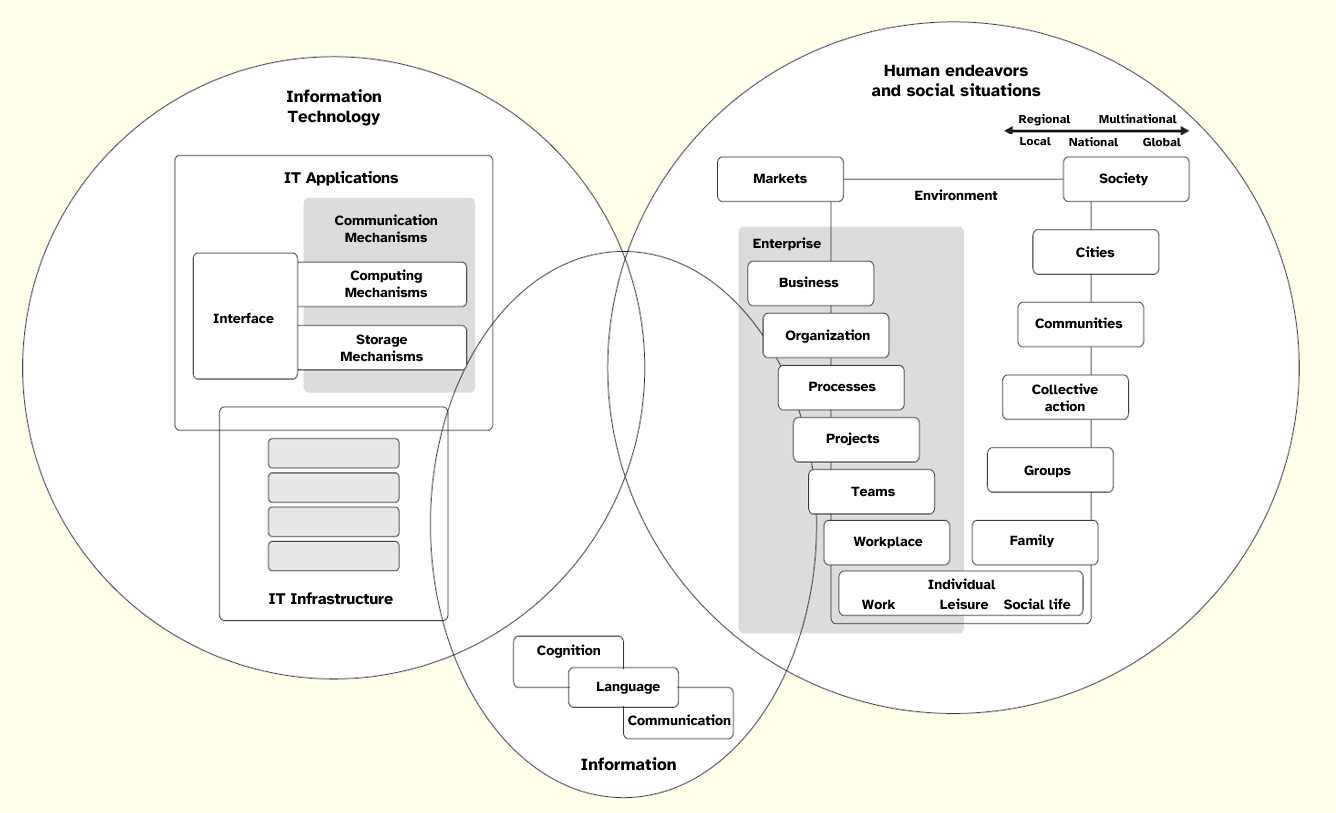

Figure 2 aims to complement the characterization of the IS field.

Figure 2: Units of Analysis in the Scientific Field of Information Systems

This characterization presents various possibilities for the units of analysis in IS. In the area of human endeavors and social situations there is the wide range of situations that contextualize the operation of IT that may be the object of attention in IS. Based on the individual, two aspects are considered: (i) the aspect that involves the individual in the context of work, carried out within the framework of a enterprise operating in a market, and (ii) the aspect of leisure and life in society that can be seen at various levels of involvement. In the background, the environment is also represented, the humanity’s common home, which has been dramatically affected by the activities of human beings and whose safeguarding is also of interest to the field of IS.

Finally, with regard to the IT area, Figure 2, on the left-hand side, begins by distinguishing between IT applications and IT infrastructure. The former include technologies that are directly related to the execution of business activities or other activities within the scope of human endeavors and social situations. The latter includes technologies that make it possible for the former to function, but which are not directly involved in those activities. Infrastructure technologies can be conceptualized in several layers, corresponding to successive levels of distance from IT applications (e.g., database management system, operating system, communications infrastructure, device drivers, firmware, and hardware). On the other hand, the components that typically make up an IT application (interface, computing mechanisms, storage mechanisms and communication or transmission mechanisms) are made explicit.

3.2 Activities on the Objects of Interest

The characterization of a scientific field cannot be limited to a description of its objects of interest and relevant phenomena. The nature of the activities on the objects of interest need to be defined. The question is whether the IS field should be understood as corresponding only to one area of research whose results essentially contribute to enriching understanding of the phenomena it encompasses, or whether it also involves activities in which its body of knowledge is applied by (IS) professionals to problem-solving and the creation of development opportunities for individuals, enterprises or society. This article takes the view that that the IS field comprises the two types of activities mentioned.

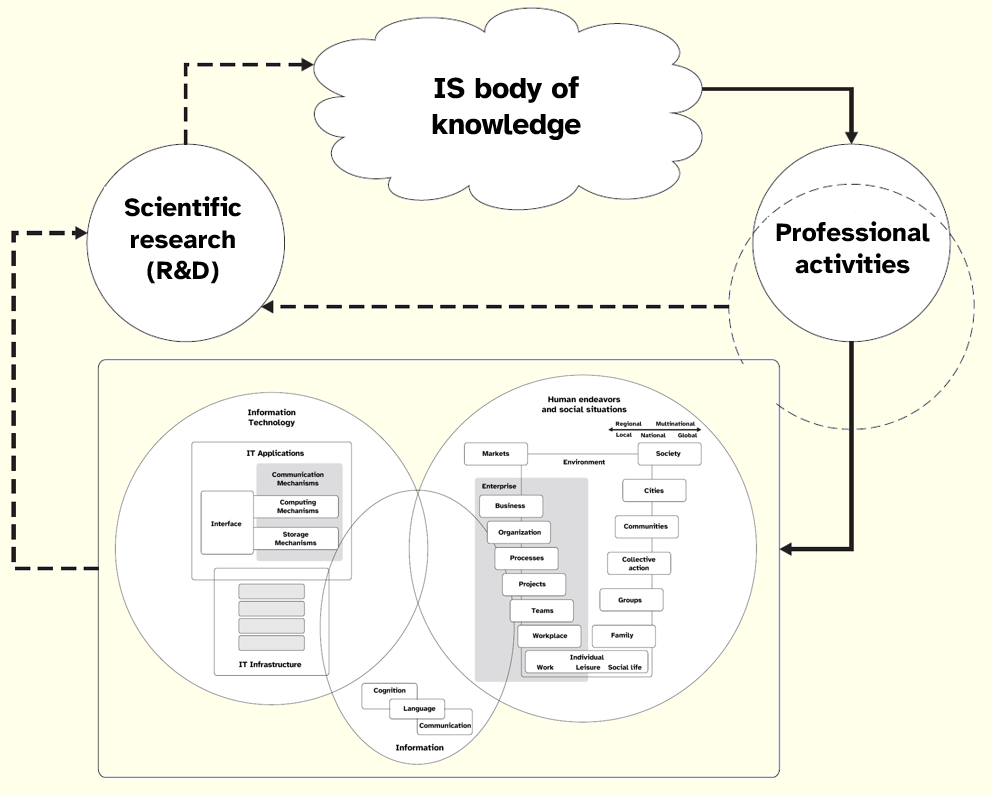

Figure 3 seeks to represent this understanding and illustrate the complementary role of these two types of activities and their relationship with the body of knowledge of the field. The left-hand side of Figure 3 illustrates the role of research and development activities to expand the body of knowledge of IS. The right-hand side shows the IS professional activities that apply that body of knowledge in interventions that, in some way, affect the objects of interest.

Figure 3: Scope of the IS scientific field, including research and development activities and professional intervention activities in situations involving the field’s objects of interest; the dashed circle on the right in the figure emphasizes that IS research also covers the activities of IS professionals

The assumption that the IS field encompasses a branch of research and development and a branch of professional activities has important consequences. On the one hand, it requires the definition of the typical functions of IS professionals. On the other hand, it requires broadening the range of forms of research to be considered under research and development activities, in order to contemplate the creation of knowledge related to the practices of IS professionals and the means and ways of working.

4. IS Professional Functions

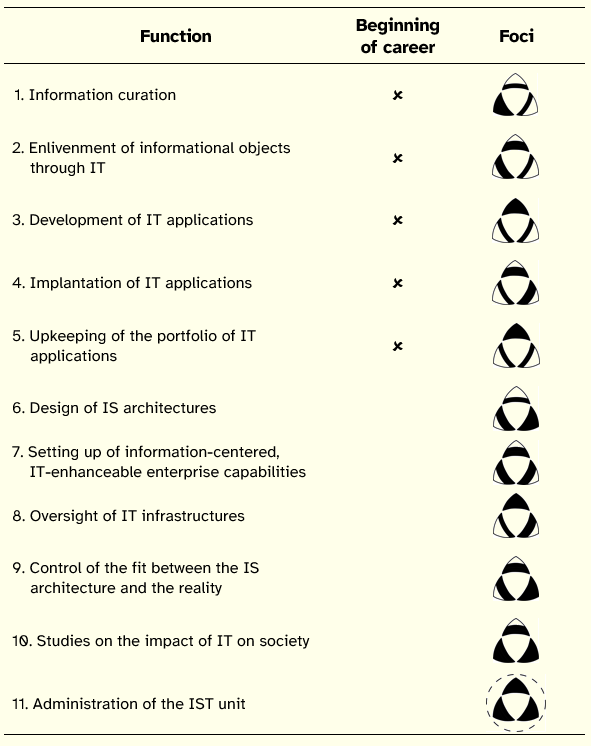

This section describes the typical professional functions of an IS professional. These functions focus on the objects of interest previously presented, thus involving the processing of information, by human and computational artifacts, within the scope of human endeavors and social situations. The functions considered are:1

1. Information curation

This function involves looking after an enterprise’s information, seeking to guarantee the availability of the information necessary for the well-being of the enterprise and the pursuit of its activities. It includes sub-functions, such as, cataloging and organizing information objects; organizing descriptions of information objects in order to facilitate their use, both by humans and by artifacts, and using computer languages that facilitate the presentation of information on digital supports.

2. Enlivenment of informational objects through information technology

It involves the use of IT to generate new information that brings benefits for the enterprise (goal-seeking entity) (solving existing problems, identifying opportunities, etc.). It includes sub-functions, such as, researching, selecting, installing and operating IT applications capable of processing and presenting information in a manner appropriate to the needs identified and the intended uses for the information; and searching, selecting, installing and exploiting IT platforms that support and enable collection, storage and retrieval, presentation and dissemination of information taking into account intended uses for information.

3. Development of IT applications

It involves designing and building IT applications, mainly by combining high-level components (content management platforms, database management platforms, workflow management platforms, component libraries, etc.). It covers the development of interface channels with users and other applications or services, mechanisms for information storage, computing mechanisms, and communications mechanisms. The development of IT applications includes establishment of the requirements that the application must meet; the requirements may have been previously defined (and will have to be interpreted and validated) or may have to be identified or defined. The development process of IT applications, in addition to establishing requirements, involves the design of the application architecture, its construction and the verification (test) that it meets the requirements.

4. Implantation of IT applications

It involves preparing and making IT applications available in the environment where they will be used. It encompasses the following sub-functions: selecting and acquiring or getting application packages—typically COTS products (Commercial-Off-The-Shelf)/RUSP (Ready to Use Software Products);2 installing and configuring IT applications; transferring existing information to the new IT application; verifying (tests) that the IT application exhibits the expected behavior and is able to meet the expectations of the intervention that frames the implantation process; adjusting the new IT application to the existing IT infrastructure and adapting this infrastructure to the new IT application; preparing the enterprise for operation of the new IT application.

The enterprise’s preparation for the operation of the new IT application focuses on organizational and social aspects, including: redefining processes/activities of the enterprise, training of the enterprise’s employees and managing organizational change.

5. Upkeeping of the portfolio of IT applications

This function seeks to ensure the proper functioning of all IT applications in operation in an enterprise. It includes related sub-functions with: ensuring integration or interoperability between IT applications; updating, upgrading, overhauling and tuning IT applications; optimizing IT applications with regard to efficiency, security, etc.

6. Design of IS architectures

The term design includes drawing up, updating and revising architectures of IS. IS architectures are representations that encompass the various aspects of IS—taking into account the purpose of the systems (and subsystems) and making explicit the interconnections between activities, information, external entities (environment), people and/or organizational units, IT applications and IT infrastructures.

IS architectures show the organizational structures related to information processing and make it easier to visualize the role that IT can play in these structures.

IS architectures are used in virtually all professional functions of IS and also play an important role in the participation of IS professionals in business interventions involving other specialties of enterprise management. Whether in interventions that require a holistic perspective of the enterprise (e.g., strategic planning, organizational design, etc.), or in interventions aimed at specific sectors of enterprises (e.g., production, marketing, sales, human resources, finance, etc.) or (transversal) aspects of the enterprise (e.g., implementation of mechanisms for quality managing, implementation of knowledge management and organizational learning mechanisms, promoting change in enterprise culture, etc.). In these interventions, IS architectures support the presentation of the potential of IT and the undertaking of activities that involve changing the processing of information, in particular those aimed at achieving the benefits arising from the use of information and IT.

7. Setting up of information-centered, IT-enhanceable enterprise capabilities

The smooth running and well-being of enterprises involves various capabilities centered on information that in some way contribute to their efficiency, autonomy, sustainability and adaptation to changes in the environment. It is not easy to identify a complete and coherent list of these capabilities. In fact, these capabilities are associated with different perspectives on the functioning of the enterprise that emphasize different facets of that functioning or that delimit some aspect of the enterprise in a different way. In some cases, different capabilities even correspond to different perspectives on the same aspect. What all capabilities have in common is that they are heavily dependent on information processing and exist in all enterprises, regardless of their size or activity sector.

The following list seeks to include capabilities that have been be the object of attention in the IS field: cooperation; coordination (by orchestration or by choreography); command and control; competitive intelligence; definition of policies; organizational design; process design; planning and control of projects; continuous improvement; business intelligence; knowledge management; organizational learning; and innovation. Underlying these capabilities, one can also consider the decision-making capability, which in turn involves: gathering information; identifying problems and opportunities; generating alternatives; choosing alternative; implementing the chosen alternative and monitoring the consequences of decisions taken. As all these capabilities are based on information processing, it is understood that they can be the object of (re)structuring (and even transformation) by the application of IT.

This function (7) involves: analyzing and diagnosing the capability in question; designing the organizational capability, taking into account the possibilities of IT; planning the organizational changes necessary in the enterprise to implement the new version of these capabilities and implementing these changes (in collaboration with other organizational experts).

8. Oversight of IT infrastructures

Oversight involves selecting, installing, configuring and adjusting IT platforms (e.g. DBMS, DW, WFMS, BI, etc.) that support IT applications; defining requirements (functional and performance) for services and IT platform infrastructure; negotiating requirements and service level agreements (SLA) for an enterprise’s IT infrastructure; and auditing of an installation and of compliance with the service level agreements of the IT infrastructure. It is considered that the design and implementation of the IT infrastructure for a personal installation or for a micro/small business are also functions of an IS professional.

9. Control of the fit between the information systems architecture and the reality

This function involves assessing the correspondence between the IS architecture (as a representation of the information system) and the way the enterprise effectively handles information. It also includes establishing and monitoring internal control mechanisms designed to prevent and detect the occurrence of errors and irregularities in information manipulation activities. In the event of significant gaps, inquiries and corrections are carried out. Scrutiny actions can focus on several aspects related to the enterprise’s information system, such as, the quality of the governance of IT and IS, the integrity of IS, the effectiveness of IT and IS with regard to meeting the enterprise’s objectives, the quality of information objects handled by the enterprise, the efficiency of IT and the need and sufficiency of the competencies, processes and resources assigned to the information systems and technology function. Conducting the evaluation activity requires special attention to provisions contained in legislation, regulations and contractual obligations that affect IS-related processes, as well as normative references which aim to standardize good practices in the management and exploitation of IT and IS.

10. Studies on the impact of information systems and technology on society

The studies help formulate policies (at local, regional, national, multinational or global level) in relation to the social, economic, political and cultural issues that might be affected by IT-related developments.

It involves activities such as: identifying impacts and influences (econometrics) of the use of IT in individuals, enterprises, markets or society; generating scenarios and exploring simulations on scenario representations, and producing justified recommendations to achieve desirable scenarios or to avoid undesirable ones.

11. Administration of the information systems and technology unit

Meta-function aimed at improving the productivity of the resources allocated to the information systems and technology function, taking into account the policies of the enterprise. It includes reporting to the enterprise’s executive management.

Table 1: Categorization of Information Systems Professional Roles

The set of functions described above forms the core of a profile that we denominate by engineering and management of information systems. Engineering and management are diffuse concepts that complement each other and that overlap. Both are related to identifying and solving problems. Both cases also involve the exercise of design in the sense used by Simon [1981] in his book The Sciences of the Artificial:

Engineering refers to functions related to artifacts whose nature, physical, chemical or biological, is a source of restrictions to its ideation, structuring, implementation and operation. For its part, management refers to looking after situations where humans are present. But it also includes deliberate structuring of such situations or influencing them so they evolve to some state considered preferable. Thus, engineering and management are distinguished.

The objects of interest in the IS field, as presented in Section 3, contribute to reinforcing the indistinctness mentioned above.

Firstly, because they include an artifact—information—which although lacks a substrate, it depends little on the laws to which that substrate is subject. The importance of this artifact lies in the meaning attributed to it by people in the context of human endeavors and social situations. Thus, although its concretization is affected by the laws of physics, in the ideation and structuring of information, the processes of cognition and communication where the information will be used are particularly important.

Secondly, the ideation, structuring and realization of the IT artifacts, although limited by physical elements—computers and their interconnections—is mainly restricted by aspects of information processing. These aspects are related to sequences of operations—algorithms—that follow rules of reasoning anchored in cognitive operations.

The engineer and manager of information systems, therefore, deals with aspects related to information processing, taking advantage of IT, in enterprises and other social situations (purposeful entities seeking to achieve goals).

5. IS Body of Knowledge

B1—Concept schemes, classifications and other forms of knowledge essentially descriptive, used to describe and characterize phenomena relevant to IS. This type of knowledge corresponds, globally, to the theories for analysis (type I theories) of Gregor’s [2016] classification.

B2—Theories that reflect an understanding of the relevant phenomena in IS. These theories cover the principles of information processing and the regularities in human and social behavior related to the information processing and the adoption and use of computer artifacts. These are theories that involve causal relationships or, at least association between the constructs involved. This type of knowledge corresponds to the theories of types II, III and IV of the classification of Gregor [2016], respectively: predominantly explanatory theories, predominantly predictive theories and explanatory/predictive theories.

B3—Methods, techniques and tools and any form of action-oriented knowledge, namely the actions inherent in the above functions enunciated (cf. Section 4), and also architectures (typical structure) of IT artifacts, both in terms of applications and infrastructure. This type of knowledge corresponds to type V theories (theories for design and action [Gregor 2016]). Methods, techniques and tools are means to achieve certain ends. They are not knowledge obtained by discovery, but by invention. This type of knowledge can thus be considered to correspond to technology [Ortega y Gasset 1983; Polanyi 1956].

C4

The development of the IS body of knowledge is the mission of the IS research activities discussed below.

6. IS Research

The nature of the objects of interest in the IS field, as well as their characteristic mutual interdependence, and the fact that it encompasses a dimension of professional practice, make the IS field particularly challenging in terms of scientific research and technological development. The challenges involve two fronts: the range of research activities that can exist and the range of applicable research methods.

6.1 Types of Research Activities and Research Results in IS

The following three types of research activities can be distinguished and correspond mainly to the production of knowledge types B2, B3, and B43 identified above and whose purposes are:

R1—Basic research: Understanding relevant IS phenomena. This type of research leads to the production of type B2 knowledge presented in Section 5.

R2

R3—Clinical research (evaluation of technology while it is being applied): Evaluating the effectiveness of the technology. This type of research leads to the production of C4 type of knowledge. Technology assessment focuses on technology that is at a high level of readiness, namely technology which is already available and in operation (TRL 9). This type of research corresponds to making the value test, i.e., it aims to establish in which conditions technology is a generator of value [Nunamaker et al. 2015]. The designation of clinical research, presented above, has its origins in the field of medicine where this type of research is well established. This designation makes it clear that this is a form of research that takes place in a real context—in clinical practice—involving professionals of the field (doctors in the case of medicine). In the case of IS field, this type of research requires the involvement of IS professionals who, in the context of their professional activities seek to contribute to the advancement of the body of knowledge of the field, evaluating the technology they apply. And not just the technology they provide to solve the problems they face, but also the technology they use in carrying out their professional functions.

Given the professional activity of the IS scientific field, it is important to consider the role of IS professionals in research. Not as objects of study (something that can also happen, particularly in type R1 research), but taking a leading role in the professional community in which they fit, translated into the involvement (possibly leadership) on research projects. It would be natural for these projects to be of type R2 or R3.

In the first case (type R2 projects), since they are aware of the situations faced by enterprises and the ways to deal with these situations, IS professionals will be particularly well placed to find new solutions to the problems and challenges faced by enterprises and also to design new methods, techniques and tools for their professional activities. In research conducted by IS professionals, it is understandable that the link between the new technology and the theoretical knowledge that supports and explains it is made a posteriori. In other words, the creation of technology (knowledge of type B3) does not result from a search for possible applications for knowledge of type B2. The creation of technology can appear intuitively. The connection with type B2 knowledge will be made after the creation of the technology, namely by understanding the new technology, its limitations and potential extensions.

In the second case (type R3 projects), the IS professional adopts a reflective and continuous improvement attitude. It reflects on its actions, seeking to measure the effectiveness, efficiency or usefulness—the value—of the technology it provides and/or of the methods, techniques and tools applied. In this way, IS professionals combine their professional action with the application of scientific inquiry methods and techniques in order to be able to measure accurately that value. This measurement will form the basis to understand the possible need to improve solutions and the existing resources and work tools.

It is also to be expected that research conducted by IS professionals will be in contexts other than laboratory research. These will be contexts in which the dimension of creating new knowledge (research) is combined with the resolution of concrete problems, such as the context of the s0-called Design Science Research (DSR), as described by Hevner et al. [2004]. Or contexts involving problem-solving in specific situations, with the participation of different stakeholders in these situations and the use of multidisciplinary approaches that make up mode 2 of knowledge production described by Gibbons [2000].

6.2 IS Research Methods and Approaches

Figures 1 and 2, which were used to characterize the IS field, are also useful for justifying that, in IS it is possible (and necessary) to use a wide range of research methods. These Figures explain the classes of phenomena that are objects of interest in the field—phenomena involving information, IT and human endeavors and social situations—and present some of the possible subclasses. The diversity of contexts in which IT operates stand out (see, for example, the right-hand side of Figure 2). These Figures also seek to illustrate the interdisciplinary nature of IS field.

It should come as no surprise, then, that in IS research it is possible to recognize the use of research methods typical of very different fields, which, since they operate at different levels of analysis, require specific research methods. Such fields include the human sciences (e.g., cognitive sciences and psychology), organization and management sciences, social sciences (e.g., sociology and economics), technology and engineering.

It is understandable, then, that in IS research it is possible to find the range of research methods established in all those fields, including: computer simulation; laboratory experiments, either involving simulating the relevant phenomena, or carrying out tests that enable the evaluation of the effectiveness of the technology (often using captured records in real situations that are used as benchmarks); field experiments (quasi-experimental studies), carried out in a basic research logic (R1), translational (R2) or clinical (R3); miscellaneous field studies, including case studies, surveys, or also the use of focus groups and other ways of obtaining opinions and perceptions from respondents recognized as privileged; studies based on documents; studies based on secondary data, with studies that use data corresponding to records created by sensors and other devices that integrate IT applications or platforms gaining importance.

The choice of one of the many methods listed depends, essentially, from the answers to two questions:

Is it possible to produce instances of the phenomena under study, so that they can be studied in a systematic and controlled way?

Is it possible to interfere with the phenomenon in some way by changing the conditions where it occurs?

Clearly, the confidence to be had in the results obtained depends on the research methods used. The hierarchy of research methods considering the quality of the empirical evidence they produce is still not common in the IS field, although it is well established in medicine (cf., for example, [GRADE 2004] and [Djulbegovic and Guyatt 2007]).

7. Conclusion

This article presents a perspective of the IS field that reflects the academic experience of their authors, namely their involvement in research, teaching and service activities, as well as in the creation/reformulation of teaching programs leading to academic degrees (study cycles/programs).

This academic experience takes place in a department—the Department of Information Systems—which is part of an engineering school—the School of Engineering at the University of Minho (UMinho). Thus, although in UMinho’s higher education in information systems also participates the School of Economics and Management, the design of teaching programs tends to follow the models of engineering education. On the other hand, the engineering school contributes to reinforcing the idea that the IS field integrates an aspect of professional activity.

With this essay, the authors seek to contribute to the ongoing efforts related to the definition of curricular recommendations for the IS field and for a debate on the cleavage between rigor and relevance that is recurrently addressed in the IS scientific community.

To follow on from the ideas presented here, the professional roles described in Section 4 can be used in various ways. Possible uses follow: to provide an additional point of view for the most recente recommendations curricula—MSIS 2016 [Topi et al. 2017] and IS 2020 [Leidig and Salmela 2021]; as a framework for analysis in order to identify which IS profiles intersect those included in the European ICT Professional Role Profiles6 or in competency frameworks such as SFIA7, and also as a framework for analysis to better understand the correspondence of the informatics engineering profession of the Order of Engineers with the IS profile [Machado and Amaral 2011].

On the other hand, this essay could contribute to repositioning the role of IS professionals in the production of knowledge, pointing out that rigor and relevance are both essential in the context of research that aims to produce empirical evidence of the technology’s effectiveness that can guide IS professionals in the various choices they have to make in their daily work.

References

van Aken, J. E. (2004). Management Research Based on the Paradigm of the Design Sciences: The Quest for Field-Tested and Grounded Technological Rules. Journal of Management Studies 41(2), 219–24.

Bacon, C. J. and B. Fitzgerald (1996). The field of IST: a Name, a Framework, and a Central Focus. Executive Systems Research Center Working Paper Series 96(5), 1–35.

Bubenko, Jr., J. (2009). Information Processing—Administrative Data Processing: The First Courses at KTH and SU, 1966-67. In Impagliazzo, J., T. Järvi and P. Paju (Eds.), History of Nordic Computing 2, Second IFIP WG 9.7 Conference, HiNC2, Turku (Finland), August 2007, 138–148.

Davis, G. (2015). Pioneering IS as an Academic Field. AIS Success Strategies Webinars 14. https://aisel.aisnet.org/success_strategies/14

Djulbegovic, B. and G. H. Guyatt H. (2017). Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. The Lancet 390(10092), 415–423.

Falkenberg, E. D., W. Hesse, P. Lindgreen, B. E. Nilsson, J. L. Han Oei, C. Rolland, R. K. Stamper, F. J. M. Van Assche, A. A. Verrijn-Stuart and K. Voss (1998). FRISCO—A Framework of Information System Concepts. IFIP—International Federation for Information Processing.

Gibbons, M. (2000). Mode 2 society and the emergence of context-sensitive science. Science and Public Policy 27(3), 159–163.

GRADE Working Group. (2004). Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The BMJ 328(7454), 1490.

Gregor, S. (2006). The Nature of Theory in Information Systems. MIS Quarterly 30(3), 611–642.

Hevner, A. R., S. T. March, J. Park and S. Ram (2004). Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly 28(1), 75–105.

Leidig, P. and H. Salmela (2021). IS2020: A Competency Model for Undergraduate Programs in Information Systems. The Joint ACM/AIS IS2020 Task Force. https://is2020.hosting2.acm.org/2021/02/07/is2020-final-report

Machado, R. J. and L. Amaral (2011). Sobre os Actos da Profissão no Âmbito do Colégio de Engenharia Informática. Revista INFO 23, 14–19.

Machlup, F. and U. Mansfield (Eds.) (1983). The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Nunamaker Jr., J. F., R. O. Briggs, D. C. Derrick and G. Schwabe (2015). The Last Research Mile: Achieving Both Rigor and Relevance in Information Systems Research. Journal of Management Information Systems 32(3), 10–47.

Ortega y Gasset, J., Thoughts on Technology. In Mitcham, C. and R. Mackey (Eds.) (1983). Philosophy and Technology—Readings in the Philosophical Problems of Technology 80. New York: The Free Press, 290–313.

Polanyi, M. (1956). Pure and Applied Science and Their Appropriate Forms of Organization. Dialectica 10(3), 231–242.

Reed, S. K. (1996). Cognition: Theories and Applications, fourth edition. Pacific Grove: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Simon, H. A. (1981). The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT press.

Stamper, R. (1973). Information in Business and Administrative Systems. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Stamper, R. (1996). Signs, information, norms and systems. In Holmqvist, B., P. B. Andersen, H. Klein & R. Posner (Eds.), Signs of Work: Semiosis and Information Processing in Organisations, 349–397. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Stanton, N. (1990). Communication, second edition. London: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Topi, H., H. Karsten, S. A. Brown, J. Á. Carvalho, B. Donnellan, J. Shen, B. C. Y. Tan and M. F. Thouin (2017). MSIS 2016 Global Competency Model for Graduate Degree Programs in Information Systems. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 40, Article 18. DOI: 10.17705/1CAIS.04018. Available at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol40/iss1/18

Vicente, M. R. and A. Novo (2014). An empirical analysis of e-participation. The role of social networks and e-government over citizens» online engagement. Government Information Quarterly 31(3), 379–387.

Endnotes

1 The description of functions is based on an understanding of various concepts, which, while supported in the IS literature, may not correspond to the most current uses of the terms they are associated with, namely:

Goal-seeking entity: an individual or collective entity with a goal. In pursuit of the goal, the goal-seeker manipulates information. Examples of goal-seekers are individuals, companies, non-profit organizations, associations, state services, government agencies and regulators.

Information: symbolic phenomena, objects or things, external to the human mind, deliberately created to be used in the context of human activities in operations that involve some kind of communication or cognition.

Information Technology (IT): hardware, software and their combinations.

Information Technology Infrastructure: information technology that provides the basis for the operation of information technology applications.

Information Technology Applications: computer-based artifacts that automate or support a goal-seeker’s information-related activities, such as capturing, storing and retrieving, transforming, transmitting and making information available.

Information System (IS): systemic view of the goal-seeker from an information perspective, i.e., focusing on the goal-seeker’s activities that manipulate information.

Information Systems Architecture: representation of the information system that shows the link between the goal-seeker’s purposes, activities, information, people, information technology applications and information technology infrastructure.

Information Systems and Technology Function: structure set up by the goal-seeker to boost the use of information in its activities.

2 An IT application implantation project may involve an IT application development sub-project. This will happen if it is understood that the development of a tailor-made IT application is necessary; because there are no suitable IT applications (COTS/RUSP), or because it is understood that it will be the best technical-social-economic option.

3 Note that type B1 knowledge is left out. B1-type knowledge establishes elementary aspects about things in the world, for example, ontologies and taxonomies and typologies. The production of this type of knowledge can take place either in basic research (R1) or in applied/translational research (R2).

4 The concept of technology readiness level was created at NASA in the 1970s. This article uses the technology readiness level scale in use in the European Union—https://enspire.science/trl-scale-horizon-europe-erc-explained

5 Following the publication of regulations that prevent the configuration of an integrated master’s degree in engineering, the Integrated Master’s Degree in Engineering and Management of Information Systems (MiEGSI) will soon be replaced by a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree that will retain the designation of Engineering and Management of Information Systems.

6 https://www.cen.eu/work/areas/ict/eeducation/pages/ws-ict-skills.aspx (based on the e-CF competency framework—https://www.ecompetences.eu).

7 https://sfia-online.org/en