Original source publication: Carvalho-Silva, M., M. T. T. Monteiro, F. de Sá-Soares and S. Dória-Nóbrega (2018). Assessment of Forecasting Models for Patients Arrival at Emergency Department. Operations Research for Health Care 18, 112–118.

The final publication is available here.

Assessment of Forecasting Models for Patients Arrival at Emergency

Department

a Department of Production and Systems, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

b Algoritmi R&D Center, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

c Department of Information Systems, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

d Hospital de Braga—Escala Braga, Sociedade Gestora do Estabelecimento, S.A., Braga, Portugal

Abstract

The unpredictability of arrivals to the Emergency Department (ED) of a hospital is a great concern of the management. The existence of more complex pathologies and the increase in life expectancy originate a higher rate of hospitalization. The hospitalization of patients via ED upsets previously programmed services and some cancellations may occur. The Hospital’s ability to predict turnout variations in the arrivals to the ED is fundamental to the management of the human resources and the required number of beds. Braga Hospital, in Portugal, is the subject of this work. Data for ED arrivals in 2 years (2012–2013), the test period, was studied and forecasting models based on time series were built. The models were then tested against the real data from the evaluation period (2014). These models are of ARIMA (AutoRegressive-Integrated-Moving Average) type, used software was the Forecast Pro.

Keywords: Forecasting Models; Emergency Department; Optimization; Health Costs

1. Introduction

In all societies, health resources are evaluated according to the populations’ perceived added value of the services they provide [Bernstein et al. 2009]. One of the main features of the National Health System is the Hospital, which is a complex system of services divided in medical specialties relying on proficient practitioners and advanced technological equipment. The Emergency Department (ED) of public hospitals are an essential part of the Health System. Its primary objective is to provide immediate and accurate health care. Situations involving long-term care are forwarded for hospitalization or for follow-up in outpatient regimen. The growing demand for urgent consultations spring from the gradual aging of the population and the lack of accessibility to primary health care, within the framework of the National Health Service. Overcrowding of emergency services is an international phenomenon that, if not correctly solved, impacts negatively on the quality of care provided, on clinical outcomes and on users’ satisfaction [Boyle et al. 2010; Hoot et al. 2009]. Several researchers have been working in this subject studying forecasting strategies to preview the arrivals to ED [Billings et al. 2013; Diaz et al. 2001; Hoot et al. 2007; Hoot and Aronsky 2008; Jones and Joy 2002; Kam et al. 2010]. The influence of some environmental variables like temperature or precipitation is also the focus of some works [Linares and Daz 2008].

Improper use of ED services is one of the most serious problems threatening their capacity to respond to acute situations, those that require an intervention of assessment and/or correction (curative or palliative) in a short period of time. According to data collected in 2010 by the reassessment of the National Network of Emergency/Urgency [CRRNEU 2012], only 54% of the cases addressed in the emergency services of Continental Portuguese hospitals were cataloged as urgent, very urgent or emergent, so yearly estimation is that 6 million episodes can be derived from overuse of Hospital Emergency Services. This ratio fluctuates on a regional basis, and the northern region presents the lowest ratio of use of Emergency Services, about 547 episodes per thousand inhabitants.

ED admissions represent more than 50% of the admissions in hospital wards, 9% of patients coming to ED will need to stay inhospital care. The in-hospital logistics must be adjusted to the everyday needs of new patients (number of beds, work teams, medications, food, etc.). The unpredictability of arrivals to the ED of a hospital is the main motivation of this work—it is crucial to the hospital’s management team have a forecasting mechanism of these arrivals.

From all the scientific articles reviewed, none of them uses data from a real production system as in this work. In this article, more than 350,000 arrivals to the ED of the Braga Hospital, a Portuguese public hospital, were collected and analyzed, and some efficient methods for their prediction based on time series are studied. This is the innovative approach of this work: to forecast the ED arrivals of the Braga Hospital, helping the Production Management team, to reach an optimum level of service.

The article is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a description of the Emergency Department of the Braga Hospital, describing how the actual system for arrivals is done. In Section 3 some definitions and information about the data are presented. The statistical experiments are reported in Section 4. Section 5 synthesizes the forecasting methods, commonly used in this type of situation [Wiler et al. 2011]. The main motivation of this work is in Section 6 - the best forecasting model and its results are presented, being compared the reliability of resulting short-term estimates to the real inflow to the ED of the Braga Hospital. Some conclusions are carried out in Section 7.

2. The Emergency Department of the Braga Hospital

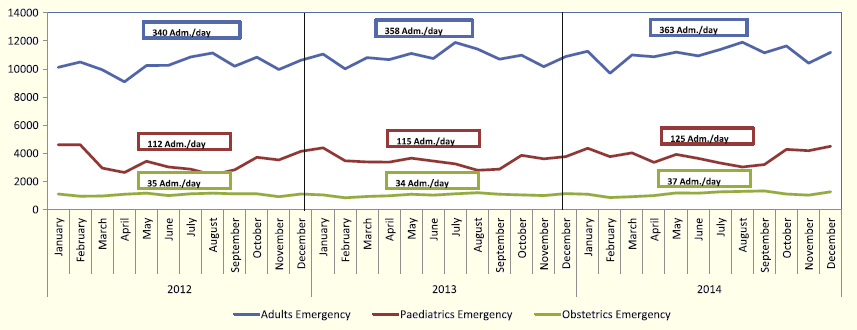

Since 2011 the Braga Hospital operates in its new facilities, directly covering a population of 275,000 and acting as second line response to the 1,100,000 inhabitants of Minho region. It features a multi-purpose emergency service that develops into three autonomous units, namely, general emergency, pediatric emergency and gynecological/obstetric emergency. For the past 3 years there has been a sustained growth of activity, mainly in general and pediatric emergencies (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Admissions to the General, Pediatric and Obstetric Emergency (2012–2014), at Braga Hospital

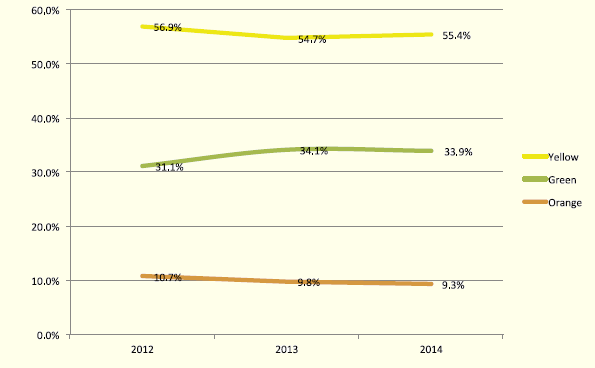

From the severity point of view, based on the Manchester Triage [GPT 2018], 65% of Braga Hospital admissions are either very urgent or urgent, but there is a slight increase in 2013 and 2014, comparing to 2012, of admissions due to matters of little urgency (green line) as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Proportional Distribution of Severity Levels through the Manchester Triage (2012–2014), at Braga Hospital

The arrival of patients to the hospital can be done in two ways: either elective, an activity programmed days or weeks in advance, or emerging, when a patient arrives at the ED in an unplanned manner. This arrival can be for reasons associated with epidemiological factors (aging population, chronicity of diseases), environmental factors (cold or heat weather peaks), economical factors (economic crisis, circumvention on payment of user fees, a decreasing use of private services) or social factors (systematic recourse to emergency services on certain days of the week and hours of the day). Studies show that the turnout to the ED is not a random process [Abraham et al. 2009; Champion et al. 2007] and very often peaks in demand are related with seasonality of pathologies, to public or school holidays, or to the time of day or day of the week. The occupation of hospital beds is broken down between elective admissions, planned in advance, and admissions through the ED (about 56% of the total hospitalizations). It is accepted as good practice that patients are admitted within 6 h from arrival at the ED (about 9% of the total patients that come through the ED). The affluence of patients through the ED raises the level of uncertainty for the need of beds to a point that frequently same-day surgical activities have to be canceled and the typology of operative plans have to be changed, favoring outpatient surgeries instead of surgical patients due to beds unavailability. As there are funding restrictions, a balance between cost and effectiveness must be obtained in resources allocation. The ability to predict the volume of demand in the ED would, in the short term, enable the correct allocation of clinical teams for emergency service assuring suitable waiting times for care, and adjusting the availability of beds in the hospital for the appropriate response to the influx of severe and urgent clinical pictures.

3. Methods

3.1 Definitions

We consider arrivals all episodes in which the patient goes through the administrative registration process, regardless of when he leaves. Upon arrival to the ED, the patient is examined by a nurse in the triage process, and is headed for a medical specialist to start the diagnosis and handling of complaints. The expectation is that his stay in the hospital will be less than 24 h, except in more complex situations that require a more prolonged clinical approach, in which case he will be forwarded to the inpatient admission. The reasons for a patient to be disqualified without completing the process are: when the patient is treated and sent back home with indications of continuity addressed to the family doctor/specialist in outpatient regimen programmed; transferred to another hospital, when the clinical situation is stabilized and the patient should return to the hospital source, in his area of residence; referenced for internment in the hospital; and, very rarely, when the patient is deceased during the episode. All episodes of abandonment, after having been administratively registered, account to the metric of arrivals to the urgency.

3.2 Study Design

From January 2012 there is reliable data for arrivals to the ED of the Braga Hospital. This information includes the patient’s name, age, gender, date and time of arrival, triage sorting, destination after triage, date and time of release, and release justification. The first phase of this work consisted in the collection and processing of the data. The predictive model will work on data collected from January 2012 to December 2013 (test period), with 177,769 arrivals on 2012 and 185,132 arrivals on 2013; the results thus obtained will be compared to the data from 2014 (evaluation period), in order to determine the accuracy of the estimates obtained by prediction of the number of arrivals.

4. Statistical Experiments

The variable under study is the arrival of users to the ED. The data from 2012 and 2013, more than 350,000 records, was treated and statistical tests were performed. All statistical analysis were performed using IBM SPSS v21 [Field 2013] and Excel 2010 [Burns and Bush 2007].

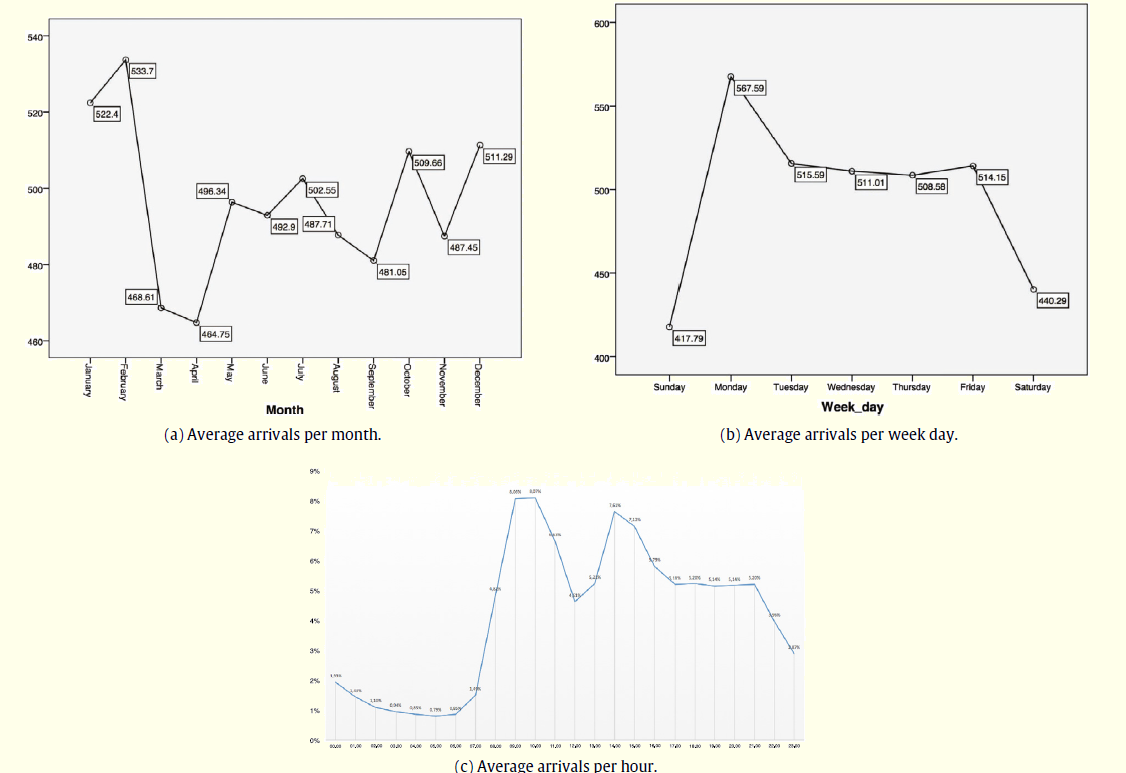

Users’ arrival to the ED was analyzed regarding the month of the year, the day of the week and the time of the day. To give an idea about the magnitude of the data, Figure 3 shows the day-average arrivals distribution per month (a), per week day (b) and along the day (c) (considering data from January 2012 to December 2013). This figure shows that the greatest demand is in February (533.7 arrivals per day), on Monday (567.6 arrivals per day) and during the day there are two peaks for increased demand which are at the start of the morning and early afternoon.

Figure 3: Average Number of Arrivals (January 2012–December 2013)

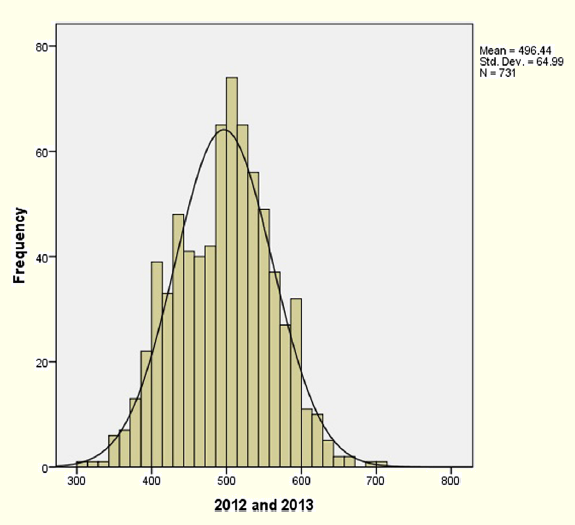

The daily arrivals distribution during the test period, Figure 4, presents an almost perfect normal distribution.

Figure 4: Arrivals Distribution during the Test Period (2012–2013)

4.1 Correlation Tests

Some authors [Diaz et al. 2001; Kam et al. 2010; Linares and Jaz 2008] suggest that maximal, minimum, mean temperature and humidity are the environmental variables that can influence the ED arrivals. Jones and Joy [2002] also use temperature and precipitation. Marcilio et al. [2013], McCarthy et al. [2008] and Wargon et al. [2010] refer that using precipitation this gives some uncertainty to the model giving also almost no improvements to the precision on the forecast. As stated in [Marcilio et al. 2013] one of the motives for different opinions on introducing or not the temperature on the forecast models are the fact that the different studies occur in different geographical areas with the ED showing different characteristics as well.

In this work several environmental variables were studied in order to identify their relation to the ED arrivals. Those that showed greater correlation were the precipitation and the maximum temperature but even these were not significant in relation to the correlation of the arrivals.

The Pearson bivariate Correlation test in SPSS produces a coefficient r that quantifies the strength and direction of the relation between two variables. The Pearson correlation also assesses the presence of statistical evidence of a linear relationship between the same time series, represented by the ρ value. The Pearson test was used to study the correlation between the arrivals to the ED and the environmental variables precipitation and maximum temperature whose data is from Underground [2001]. Regarding precipitation and arrivals, the result was r(ρ) = −0.102(0.006). This correlation coefficient characterizes a weak negative linear relationship between the variables, i.e., arrivals decrease with an increased level of precipitation. Regarding arrivals and maximum temperature there is no correlation, according to the result r(ρ) = −0.028(0.457). The same tests were made for the holidays, and the results obtained r(ρ) = −0.188(p) with p < 0.01, concludes for the existence of a

weak correlation.

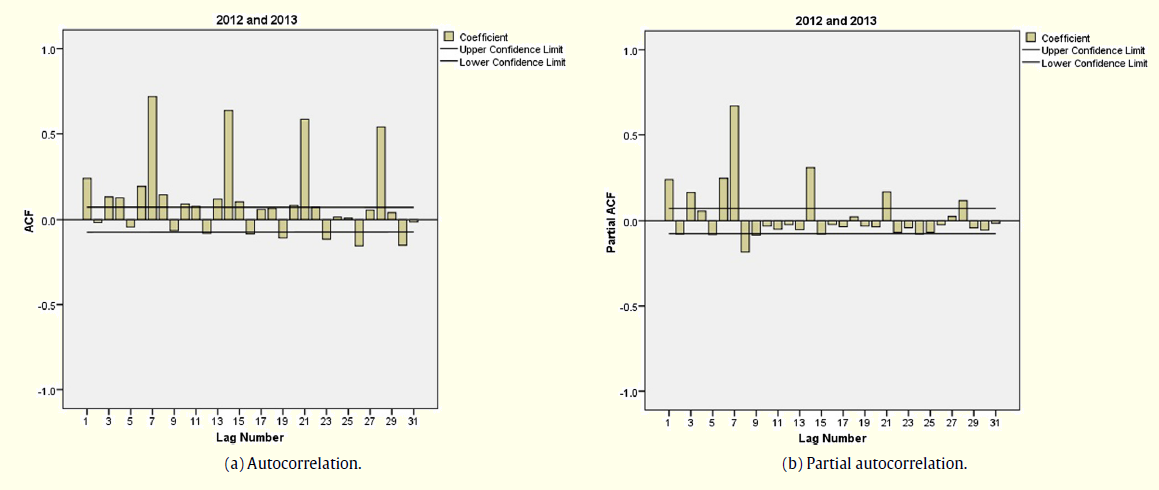

4.2 Autocorrelation Test

Autocorrelation is the self linear dependence of a variable in separate moments. It is a statistical measure that indicates the relation between values of the same variable separated in time. For example, the autocorrelation of period 1 measures the ratio between consecutive values of the variable while the autocorrelation of period 12 indicates the relationship between values separated by 12 periods of time. These tests measure the degree of association between two observations, Yt and Yt−k, when the effects of the periods prior to k(1, 2, 3, . . . , k − 1), are eliminated.

The tests showed a strong correlation on 7 days’ time series of arrivals. A partial autocorrelation was identified, heightening the correlation between each 7 days period, with even greater emphasis on adjacent days (Figure 5). The results obtained in the autocorrelation tests will be a determining factor for the construction and improvement of the prediction model to implement.

5. Forecasting Methods

Statistical tests having been carried out, the next step would be the definition of a forecasting model for the number of arrivals to the ED. There are several types of models, such as the Moving Average, the Exponential Smoothing, the Holt-Winters, the ARIMA, among others. These models have been used in areas such as Finance, Statistics, Economics, Operations Research, Industry and Health [Wargon et al. 2010].

Several types of forecast models were tested, and final choice was for ARIMA type models (Auto Regressive-Integrated-Moving Average) [Gerolimetto 2010], so these will be further explained. ARIMA models provide an approach to time series and forecasting and are one the most widely-used methodologies to time series forecasting, providing complementary approaches to the problem. ARIMA models aim to describe the autocorrelations in the data and use the following

notation:

ARIMA(p, d, q)

where p is the order of the autoregression process (AR), d is the degree of differentiation involved (I) and q is the order of the Moving Average process (MA). To make the time series stationary (trend removal), it is previously made d differences between the data. The mathematical expression for this kind of models

is:

Yt = φ1Yt−1 + φ2Yt−2 + ... + φpYt−p + et − θ1et−1 − θ2et−2 − ... − θqet−q

where Yt is the variable value at time t, φ and θ are the model parameters for the autoregressive and moving average terms, respectively, and et are the residual term representing random disturbances that cannot be predicted [Makridakis 1989]. Although there is no limit to the variety of ARIMA models, in practice it is seldom necessary to use values of p, d and q above 2. It is worth noting that only three values 0, 1 or 2, to the parameters p, d and q, are sufficient to represent the wide range of time series, from the most diverse contexts.

ARIMA models are also capable of modeling a wide range of seasonal data. The seasonal ARIMA model is formed by including additional seasonal parameters and is written as follows:

ARIMA(p, d, q)(P, D, Q)s

where P, D and Q represent the same as p, d and q for the seasonal part of the model, and s is the number of periods in a seasonal cycle.

These models have the following characteristics: theoretically they are suitable for most data series; they are able to model variations, trends, autoregressiveness and seasonally moving average; an univariate approach method, it requires no external data; also, the statistical software is widely available.

5.1 Accuracy Measurements

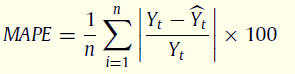

In this study, accuracy was used as the main criterion for selecting a forecasting method, and our assessment of forecast accuracy is based on the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) metric:

where Yt and Ŷt are the real arrivals and the forecasted arrivals in time t, respectively and n is the number of time units. This measure was used to evaluate and compare the performance of the studied models in the test period. An independent scale statistic as the MAPE enables the direct comparison of a model forecast over multiple time series.

Figure 5: Autocorrelation Test

6. Results

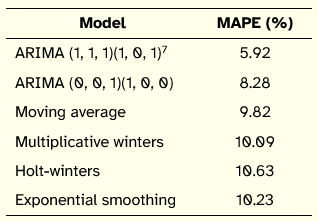

Experiments were made with various types of models using Oracle Crystal Ball software [Gentry 2008] and Forecast Pro V 3.0 [Delurgio 2005]. In the Table 1 are the MAPE values for some of these models, using test period arrivals (2012–2013).

Table 1: MAPE Values for Six Models

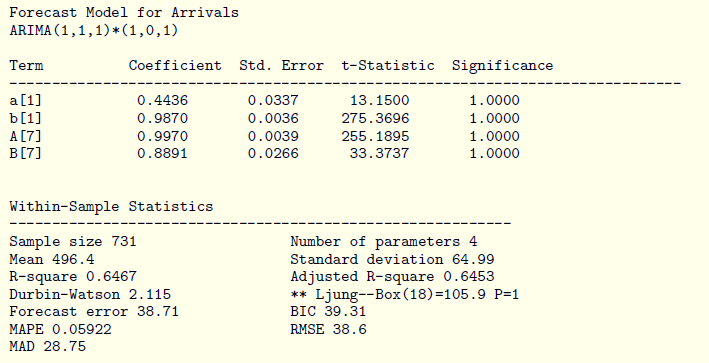

The best model for the test period was the ARIMA (1, 1, 1) (1, 0, 1)7 with MAPE = 5.92%:

Yt = 0.4436Yt−1 − 0.9870et−1 + 0.9970Yt−7 −0.8891et−7 + et (2)

followed by ARIMA (0, 0, 1)(1, 0, 0) with MAPE = 8.28%:

As already identified in the autocorrelation test, the s value, number of periods in a seasonal cycle, is 7 days. The report provided by the software Forecast Pro for ARIMA (1, 1, 1)(1, 0, 1)7 model (2) is:

Using the ARIMA (1, 1, 1)(1, 0, 1)7 model (2), the forecast for the evaluation period (2014), gives MAPE= 6.34%. The fact that the arrivals for 2014 is actual data, allows to evaluate the performance level of the forecast model.

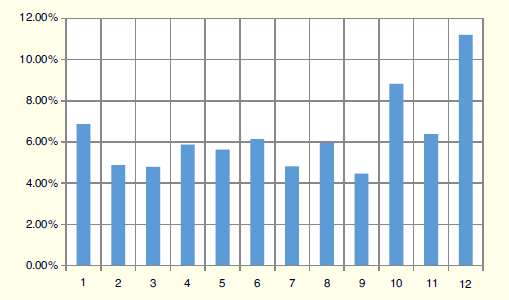

Figure 6 displays the monthly values of MAPE for 2014. As shown, there are 4 months with a lower than 5% MAPE forecast. The increase in the error throughout the year denotes possible relevance to obtain short-term estimates, taking into account the variability influx of ED, which is independent of seasonality.

Figure 6: Monthly MAPE Values Forecast for 2014

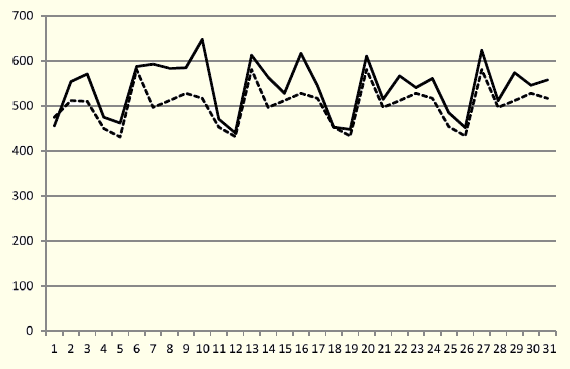

Figure 7: Forecasted Values (dashed line) vs. Actual Data (solid line) for January 2014

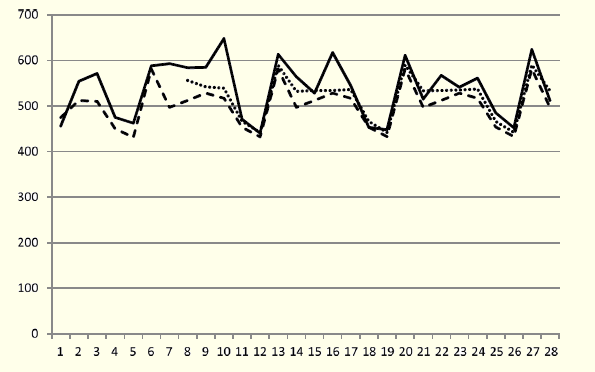

Figure 8: Forecasted Values (dashed line, dotted line) vs. Actual Data for the Last Three Weeks of January 2014

Aiming to only predict arrivals next week the model behaves with very good performance. This observation shows that the knowledge of the previous week’s arrivals is very important for a more accurate forecast.

7. Conclusions

Due to the high complexity of resources associated with the operation of the ED, the importance of forecasting models of arrivals is absolutely critical for resource planning in the hospital. The obtained model allows predictions for a week or a month with a very good quality level. Accurate forecasting of ED arrivals decreases the cancellations of planned admissions and optimizes

the beds allocation to the real demand. The human resources allocation is also adjusted according to the needs of beds and the number of work stations to patient care in the ED, with the aim of providing universal access to healthcare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) by the ALGORITMI R&D Center and project PEST-OE/EEI/UI0319/2014. The authors are very grateful to the Hospital de Braga—Escala Braga, Sociedade Gestora do Estabelecimento, S.A., for providing the data.

References

Abraham, G., G. B. Byrnes and C. A. Bain (2009). Short-term forecasting of emergency inpatient flow. IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine 13(3), 380–388.

Bernstein, S. L., D. Aronsky, R. Duseja, S. Epstein, D. Handel, U. Hwang, M. McCarthy, K. J. McConnell, J. M. Pines, N. Rathlev, R. Schafermeyer, F. Zwemer, M. Schull and B.R. Asplin (2009). The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes, society for academic emergency medicine, emergency department crowding task force. Academic Emergency Medicine 16(1), 1–10.

Billings, J., T. Georghiou, I. Blunt and M. Bardsley (2013). Choosing a model to predict hospital admission: An observational study of new variants of predictive models for case finding. BMJ Open 3(8)..

Boyle, J., M. Jessup, J. Crilly, D. Green, J. Lind, M. Wallis and G. Fitzgerald (2010). Predicting emergency department admissions. Emergency Medicine Journal 29(5), 358–365.

Burns, A, C. and R. F. Bush (2007). Basic Marketing Research using Microsoft Excel Data Analysis. Upper Sadle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Press.

CRRNEU (2012). Reavaliação da Rede Nacional de Emergência e Urgência. Comissão de Reavaliação da Rede Nacional de Emergência/Urgência

Champion, R., L. D. Kinsman, G. Lee, K. Masman, E. May, T. M. Mills and R. J. Williams (2007). Forecasting emergency department presentations. Australian Health Review 31(1), 83–90.

Delurgio, S. (2015). Guide to Forecast Pro from Windows. http://forecast.umkc.edu

Diaz, J., J. C. Alberdi, M. S. Pajares, C. Lopez, R. Lopez, M. B. Lage and A. Otero (2001). A model for forecasting emergency hospital admissions: effect of environmental variables. Journal of Environmental Health 64(3), 9–15.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th edition. London, England: SAGE Publications.

Gentry, B., D. Blankinship and E. Wainwright (2008). Crystal Ball User Manual 11.1. Oracle.

Gerolimetto, M. (2010). ARIMA and SARIMA Models. http://www.dst.unive.it/margherita/TSLectureNotes6.pdf

GPT (2018). Sistema de Triagem de Manchester. Grupo Portugus de Triagem. http://www. grupoportuguestriagem.pt

Hoot, N. R. and D. Aronsky (2008). Systematic review of emergency department crowding: Causes, effects, and solutions. Annals of Emergency Medicine 52(2), 126–136.

Hoot, N. R., C. Zhou, I. Jones and D. Aronsky (2007). Measuring and forecasting emergency department crowding in real time. Annals of Emergency Medicine 49(6), 747–755.

Hoot, N. R., S. K. Epstein, T. L. Allen, S. S. Jones, K. M. Baumlin, N. Chawla and D. Aronsky (2009). Forecasting emergency department crowding: An external, multicenter evaluation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 54(4), 514–522.

Jones, S. A. and M. P. Joy (2002). Forecasting demand of emergency care. Health Care Management Science 5(4), 297–305.

Kam, H. J., J. O. Sung and R. W. Park (2010). Prediction of daily patient numbers for a regional emergency medical center using time series analysis. Healthcare Informatics Research 16(3), 158–165.

Linares, C. and J. Daz (2008). Impact of high temperatures on hospital admissions: Comparative analysis with previous studies about mortality (Madrid). European Journal of Public Health 18(3), 317–322.

Makridakis, S. and S. C. Wheelwright (1989). Forecasting Methods for Management, fifth edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Marcilio, I., S. Hajat and N. Gouveia (2013). Forecasting daily emergency department visits using calendar variables and ambient temperature readings. Academic Emergency Medicine 20(8), 769–777.

McCarthy, M. K., S. L. Zeger, R. Ding, D. Aronsky, N. R. Hoot and G. D. Kelen (2008). The challenge of predicting demand for emergency department services. Academic Emergency Medicine 15(4), 337–346.

Underground, C. W. (2001). Weather underground. http://portuguese.wunderground.com

Wargon, M., E. Casalino and B. Guidet (2010). From model to forecasting: a multicenter study in emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine 17(9), 970–978.

Wiler, J.L, R. T. Griffey and T. Olsen (2011). Review of modeling approaches for emergency department patient flow and crowding research. Academic Emergency Medicine 18(12), 1371–1379.