Original source publication: Brito, M. A. and F. de Sá-Soares (2014). Assessment Frequency in Introductory Computer Programming Disciplines. Computers in Human Behavior 30, 623–628.

The final publication is available here.

Assessment Frequency in Introductory Computer Programming Disciplines

Department of Information Systems, Centro Algoritmi, School of Engineering, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

Introductory computer programming disciplines commonly show a significant failure rate. Although several reasons have been advanced for this state of affairs, we argue that for a beginner student it is hard to understand the difference between know-about disciplines and know-how-to-do-it disciplines, such as computer programming. This leads to failure because when students understand they are not able to solve a programming problem it is usually too late to catch all the time meanwhile lost. In order to make students critically analyse their progress, instructors have to provide them with realistic indicators of their performance. To achieve this awareness and to trigger corrective actions in a timely manner there is a need to increase assessment frequency. This paper discusses how this can be done, analyses benefits of the proposed approach and presents data on the effects of changes in assessment frequency for a university first year course in fundamentals of computer programming.

Keywords: Assessment Frequency; Computer Programming; Constructivism; Learning

Novice Students; Programming Education

1. Introduction—Reasons for Failure

The literature identifies several reasons for students failure when learning to program [Robins et al. 2003], with some addressing the curriculum, others focusing on methodologies [Cook 2008], on resources, or on the best first programming language to use [Duke et al. 2000]. The inherent difficulty of programming [Teague and Roe 2008; Winslow 1996] and controlling what kind of mistakes students are more likely to make [Spohrer and Soloway 1986] are also addressed.

However, a well-known empirical truth about teaching programming is that a motivated student needs little guidance so he will succeed no matter how bad are the overall conditions, teachers included. Similarly, a student not motivated to spend some weekly hours practicing will fail no matter what the teacher says or how well the teacher explains all about computer programming.

Our teaching practice also led us to note that many students do not have a realistic idea about their effective study performance.

Some think that understanding the solutions presented by the teacher or book is enough. They will probably try to solve their first problem during the assessment itself.

Others go a little further and do some exercises but stop training as soon as they reach a solution for a certain kind of problem. However, being able to solve a 10-min problem in a couple of hours is far from sufficient and probably the student is not even sure how the solution works.

A more insidious kind of problem emerges with students that always study in a (same) group. Frequently, what happens is that although everyone follows and contributes to the solution, it is always the same student that performs the first step from the problem statement. The others just follow the lead and genuinely believe they can alone solve the problem from the very beginning.

In this paper the main concern is to address the need to persuade students to critically analyse their study methodology and progress over the semester. So the focus is on failure reasons that can be overcome by tuning computer programming methodology of study.

Papers about difficulties in computer programming learning can be found in the literature [Jenkins 2002]. In [Gomes and Mendes 2007] difficulties are divided into five categories:

The teaching methods—this addresses the lack of personalized supervision and immediate feedback. Teachers must ensure students follow the most appropriate learning approach while respecting different learning styles, such as individual vs. group study.

The focus on syntactical details instead of promoting problem solving capabilities also needs to be addressed.

The study methods—learning computer programming is a very experimental and intense task, much different of other disciplines students are used to that are based on formulas or procedures memorization. Programming demands a lot of extra class work.

The student’s abilities and attitudes—there is a students’ generalized lack of problem solving capabilities. They read the problem description instead of analyzing it and jump to solve something prior to understand the problem. They also lose many learning opportunities because when facing a difficulty they simply give up or ask for help which basically leads to the same outcome.

The nature of programming—the high level of abstraction needed and the syntax complexity are also mentioned as difficulties.

The job of programming requires skills such as analytical thinking, creative synthesis, and attention to detail. An additional fundamental skill is the ability to abstract, consisting in ‘ ‘ The syntax complexity of programming languages raises several difficulties to novice programming students, since they may have to simultaneously struggle with the inherent complexity of the problem that has to be solved and the syntactical specificities of the programming language used to convey the computational solution to the problem.

Psychological effects—the lack of motivation for several possible reasons, being well known that an unmotivated student will hardly succeed. This is aggravated by the fact that programming courses usually gain a reputation that passes from student to student of being difficult that so many of them start already feeling defeated. There is also the fact that computer programming is usually taught at the very beginning of higher education courses, coinciding with a transition and instability period in the students’ life [Teague 2008].

2. Constructivism in Education

Constructivism is a learning theory in which Jean Piaget argues that people (and children in particular) build their knowledge from their own experience rather than on some kind of information transmission.

Later, based on Piaget’s insights on the experiential learning paradigm, important works have been developed, such as Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model [Kolb and Fry 1975] which reinforces the role of personal experiment in learning and systematizes iterations of reflection, conceptualization, testing and back again to new experiences. A rich set of works about constructivism in education can be found in [Steffe and Gale 1995].

Meanwhile, the discussion was brought to the computer science education field, with the claim that real understanding demands active learning on a lab environment with teacher’s guidance for ensuring reflection on the experience obtained from problem solving exercises. In other words, passive computer programming learning will likely be condemned to failure [Ben-Ari 1998; Hadjerrouit 2005; Wulf 2005].

Indeed, effective learning according to the constructivist perspective demands the mental construction of viable models. As argued by [Lui et al. 2004], learning to program is a difficult endeavour because the learning process is susceptible to several hazards. Although all students face these hazards [Lui et al. 2004] observe that weak students get stumbled and stalled more easily when they encounter such hazards. From our experience of teaching computer programming courses, we think that the characteristics of weak students that magnify the impacts of those learning hazards are, to some extent, shared by

the average novice student of computer programming—the student population target of this paper. Those characteristics include lack in training in abstraction processes, lack of a prior foundation for anchoring the construction of new knowledge, and low levels of confidence in themselves, in the teachers, and in the study materials or practices.

The main reason for the authors’ concern with constructivism is the conviction that teaching must always be focused on the people learning process. Even in organizations in general, there is already the belief that the integration of knowledge has achieved limited success primarily because it has focused on treating knowledge as a resource instead of focusing on the people learning process [Grace and Butler 2005].

3. Why Weekly Assessment

An interesting study that crosses students’ individual cognitive level with the types of errors made [Ranjeeth and Naidoo 2007] suggests the need to adopt innovative strategies in order to counter the seemingly perpetual rate of failure and at the same time increase the intensity for students with better cognitive level.

Whatever the reason, the ultimate truth is that a lot of things can go wrong when learning computer programming, especially in undergraduate courses.

So it is virtually impossible to prevent them all, mainly because students tend to overestimate their own understanding [Lahtinen et al. 2005] and usually they are not very open to follow teacher’s good advices, especially if following those advices means more work.

This leads to the only winning strategy we have found so far: fail fast to learn sooner. If frequent assessment opportunities are given to the student, no matter the reason why he is eventually performing badly, two important goals are immediately achieved:

there is still time to change student’s study methodology and

the teacher finally gets some real attention from the student to his good advices.

Even for students who do not need to fail to correct eventual study errors, we observe that weekly assessment is an extra motivation for not postponing study and consequently they will also attend next class better prepared [Becker and Devine 2007].

Other medium term issues related with tuning the discipline from year to year are also addressed by weekly assessment. The ordering of different concepts by difficulty [Milne and Rowe 2002] can be inferred from final examinations or by directly asking students and teachers, but if we have automated weekly assessments this kind of data is readily available. So it is easier tuning the classes’ distribution along the year, dedicating more time and exercises to those issues we know students need more time to assimilate and eventually to concentrate easier subjects in less classes.

4. How Weekly Assessment

Weekly assessment involves several dimensions. First we need a methodology and then implementation resources. For the methodology we have a set of supposedly good advices and tutorial support during classes but in this context it is enough to focus on the method the students need to follow each week (those implementation resources, advices and tutorial support will be addressed in future research reports).

4.1 Our Method

Our learning methodology includes a method of weekly work composed of the following steps:

First read the book: the students should always read the main reference of the course before attending the class. This is a well known way of preparing the brain to the concepts that will be discussed in class. It is not intended or expected that the students understand everything but they will have a precious idea of the main concepts and techniques addressed in the current week.

Participate in the class: in the subsequent class, concepts and techniques will be put in context, examples will be given and expected difficulties will be dealt with. Although students need to practice to learn to program, they should leave the class with the concepts and techniques well known. They now knowabout, they have an idea of how-to-do-it, they are prepared to go on and try to do it by themselves.

Try everything: then go back to the book and class notes and believe nothing—code everything and experiment in the programming environment. Revisit everything that was read and said, always coding it. Introduce changes in the exercises and check if the outcome matches the expected result. Solve and run the associated exercises. The biggest problem is not understanding the basic concepts or techniques but rather learning to apply them [Lahtinen et al. 2005].

Use the laboratorial classes to self assessment: a special set of exercises is weekly prepared for the students to perform a self assessment. The laboratorial class is usually used for that purpose.

Assessment: finally, the weekly assessment gives feedback to the student about the effectiveness of his work that week. This is very important for several reasons such as avoiding study relaxation, creating a timely alert to students’ ineffective study, and pinpointing the parts of the syllabus that require revision by the student.

Tutorial guidance: with the feedback provided by the assessment it is crucial to discuss the success of each student so far. Computer programming is to some extension a yes or no competence. This means that grades near zero and grades near hundred per cent are usually normal. So in the first weeks, grades bellow 80% should be carefully analyzed—what happened that justifies that the student did not reach 100%? Not enough study? Not enough experimental practice? Should he study not more but better? The role of the lab sessions teacher is crucial at this point. There are different students’ capabilities and the teacher must have answers to all of them, even if they are spread by different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy [Lister and Leaney 2003]. He must diagnose and address the personal difficulties of each student giving him guidance and self confidence.

Besides the already mentioned advantages from each step of the method, the whole set addresses main constructivism claims since it provides systematic progressive interactions with the same concepts and techniques under teacher’s guidance and consequently facilitating students’ reflection and apprehension.

4.2 Self Assessment

Students have a weekly project composed of exercises similar to the ones in the weekly assessment. Once their weekly study is done, and only then, they try to solve all the questions in order to self assess their knowledge.

In case of difficulties they should go back to the book or ask teacher for guidance.

The resolution of the project is submitted to teachers for control purposes.

4.3 The Weekly Assessment

The weekly assessment is not just a weekly assessment—it is a weekly assessment with weekly feedback, i.e., the main goal is not just to put some pressure on the students. It would not be the same if the students did weekly assessment but only obtain the grades at the end of the term. An important feature is that each student gets immediate feedback and can still correct in time his study methodology.

Unfortunately, it is incredibly simple for a very well intentioned student to diverge from the success path without notice.

We are dealing with novice first year undergraduate students and it is never too much to stress that we are dealing with novice first year undergraduate students... This means an extra charge of distractions aside from the inherent adaptation issues.

Completely out of that path of success is the temptation to stop studying after understanding a problem’s solution, but before knowing how to do it himself. Even if the student gets to the solution of a kind of problem he must consider the time that was necessary to do it—usually, it is still a long way between the points I-can-solve-it and I-can-solve-it-fast-enough.

It is also not rare that students study a lot and know very little, just because they are not doing it well. For instance, a student can spend daily hours studying syntax issues, solving problems and theoretical questions without really solving any problem himself. This translates into a deficient level of knowledge with the aggravating circumstance of inducing the student in a pseudo state of accomplishment.

Nevertheless, if by any chance an already rare student perceives or suspects of flaws in his study methodology the normal tendency will be to postpone eventual corrective measures even if he knew one and generally that is not the case.

But even worse than that is the situation of a student that has the chance to have an attentive teacher that diagnosis one of those described issues and gives the student guidance and concrete corrective measures... nevertheless the standard student will not trust the teacher’s diagnosis.

All these issues can be solved in time if one gives the student the opportunity to fail fast if something is going wrong. This opportunity is called weekly assessment and in our view it constitutes the differential factor that allows the student:

To perceive that there is an issue to address.

To believe the issue should be addressed.

To believe the issue will not disappear by itself.

To address it in time.

Weekly assessment will give the student the opportunity to correct whatever may be wrong without having to wait till next (year or semester) edition of the course.

4.4 Implementation Resources

Some authors ([Costello 2007; Duke et al. 2000]) agree on the merits of frequent assessment but have a small enough number of students or a big enough number of teacher x hours.

We do not have such resources and have almost 200 students and only a lab sessions teacher. Nevertheless, a third factor in the equation may be automated testing of the problems solved by students.

As discussed further in this document, the use of an expanded learning management system (LMS) helped solving the lack of resources issue, but also turned out to be a central point of information that the students appreciate. As concluded in [Grace and Butler 2005], LMS benefits are wide and include:

Users empowerment in managing their own learning.

Facilitating the creation of learning structures and processes.

Encouraging the routinisation of learning.

Promoting a learning culture.

5. Our outcomes with weekly assessment

Since we introduced weekly assessment the number of retained students was dramatically reduced.

However, this is not possible without some extra resources. In the case we choose to invest in automated assessment.

5.1 Addressed Reasons for Failure

Weekly assessment proved to be a powerful tool in addressing computer programming learning difficulties. Even when not directly involved, sometimes facilitates dealing with those issues.

Following the above identified five categories of reasons for computer programming learning failure, weekly assessment virtues are here analyzed:

The teaching methods: the immediate feedback provided by automated tests allows the teacher to analyse each student situation individually and to give the consequent best guidance to the student. Weekly assessment does not address the eventual excessive focus on syntactical details but gives the teacher the possibility of being aware in time of student’s eventual lack of problem solving capabilities. Anyway in this course syntax would never be an issue because of the programming language that is used.

The study methods: learning computer programming is a very experimental and intense task. It is hard to keep the rhythm week after week because a lot of distractions may occur in the student’s life. Weekly assessments mark the cadence and even in bad weeks the student will make an extra effort to keep

the pace.The student’s abilities and attitudes: the lack of problem solving capabilities is indeed a major issue. Weekly assessment gives the teacher the opportunity to repeatedly, week after week, identify students with this kind of difficulty and insist in analyzing methodologies that hopefully will tend to pay still in time. Fast opportunity of failure is good to get the student attention but also carries out repeated opportunities for changing or improving less positive attitudes.

The nature of programming: the high level of abstraction needed and the syntax complexity have already been addressed in this discussion. For those students with more difficulty at this level we do not know alternatives to practice a lot. In this sense, the rhythm imposed by weekly assessment is a great help, assisting in the formation of sound study habits by the students.

Psychological effects: it is our experience that the above mentioned psychological effects may be addressed in great extent. Weekly grades force the students to talk and exchange experiences which avoid silent postponing of anguish and suffering. Once again it also furnishes the teacher with the knowledge and the opportunity to quickly point the light at the end of the tunnel.

5.2 Success Evolution

A first and strong indicator of the weekly assessment success is the evolution of the percentage of students that stay till the end, i.e., that do not drop at the middle of the semester.

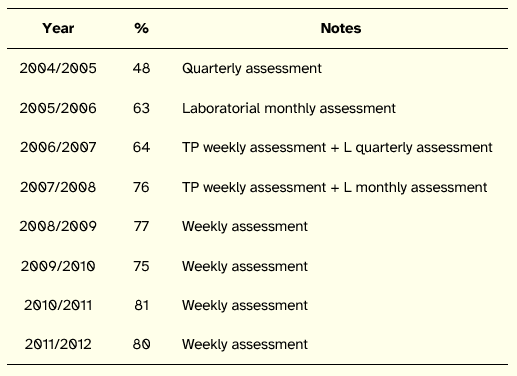

Table 1 shows this evolution for the last eight years. The reading of this table is not completely linear because some other factors changed meanwhile, such as instructors, programming language, and the redesign of the study plans due to the Bologna process. However, the evolution is quite clear and shows that the efforts in increasing the assessment frequency resulted in greater percentage of students that stick till the end of semester.

Table 1: Students that Stick Till the End of Semester Percentage Evolution

In 2004/2005 a small project was quarterly assessed; i.e., there were two assessment points per semester.

During 2005/2006 small problems resolution in computers’ lab were added to the assessment on a monthly basis.

In 2006/2007 a weekly automated theoretical-practical (TP) assessment was implemented and complemented with a quarterly laboratorial (L) assessment.

During 2007/2008 the frequency of laboratorial assessment was increased to monthly.

Finally, 2008/2009 was the year when the whole assessment was automated and weekly performed.

The ratio of approval is also growing—4% in 2005/2006, 2% the year after, 1% in 2007/2008 and finally a huge 13% jump on 2008/2009 with the weekly fully automated assessment—a 20% total improvement in five years! Since then, the ratio has stabilized in the range 75–80%. It should be mentioned that this evolution was achieved neither by shrinking the syllabus nor by decreasing the level of rigor imposed to the course over the years.

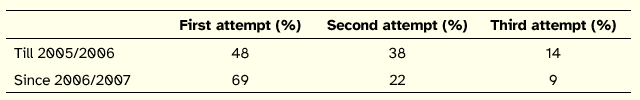

Another important indicator is the number of students being able to succeed the discipline on first attempt or better said the number of attempts a student needs in order to succeed.

For Table 2 construction we considered the division success-before and success-after weekly assessment implementation.

Table 2: Percentage of Approvals in First, Second and Third Attempts

(each attempt takes place in a different academic year)

Achieving success in first attempt is very important for several reasons. There is an associated cost for the student which is both monetary and functional. For teachers and university second attempts represent an increased complexity in resources and management.

Consequently, a 21% increment in first attempt success is a very positive result.

5.3 Students’ Opinion

Weekly testing is a key factor for success in our methodology and it has proven results. Nevertheless, results can still be reinforced with the students’ perceptions–after all they are a highly involved and interested part in this process.

Our Farewell questionnaire asks for the students’ opinion and they agree with us. When asked about, in the whole discipline, what they consider to be the most positive factor, almost 25% of the students indicate weekly testing.

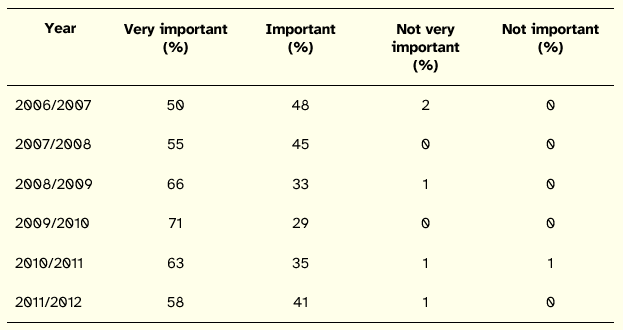

When directly asked about weekly testing, students are almost unanimous in their answers as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3: Farewell Question—Importance of Weekly Testing

The growing strength of favorable opinions about weekly testing is probably influenced by the yearly improvement in the automated testing platform. In fact, our programming extension began to be just a submit-once-without-feedback scheme which provoked many wrong answers due to very small errors, such as syntactical ones. I 2008/009 we achieved a version that allows multiple solution submissions of the same problem during the available time. Although the system does not tell the student where the errors are located, it informs the student that the proposed solution is not correct, providing him with the opportunity to search for and correct mistakes in the programming code, before grading the answer.

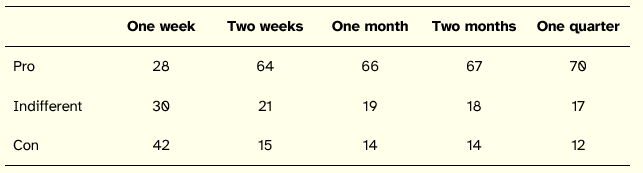

We find automated tests not to be the ideal solution but a needed one. Nevertheless, students appear to like or at least not to dislike this solution. To evaluate the possibility of doing manual assessment by enlarging the interval between assessments, i.e., doing fewer assessments, we were surprised by the fact that just a minority of students was against automated testing even in the case of being possible to perform weekly manual assessments. Obviously, as suggested by Table 4, that presents average results from 2008/2009 to 2011/2012, for a total of 480 responses, more students prefer automated tests if the alternative is to decrease the number of assessments, but even with a large number of manual assessments they still prefer automated assessment.

Table 4: Farewell Question—Weekly Automated vs. Manual Assessment

That is 64% of the students prefer a weekly automated assessment than a manual one with a two weeks interval; only 15% prefer this manual assessment. When asked about a quarterly manual assessment the percentage of students preferring automated assessment grows to 70% and the percentage against decreases to 12%.

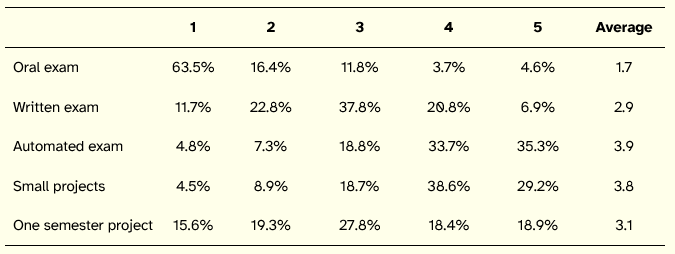

These somehow unexpected results led us to the introduction of a new question in 2008/2009, to explicitly ask students for their preferable way of assessment regardless of any other considerations.

Using a Likert scale with five positions, from one (I totally dislike) to five (It is my favourite assessment type) the students’ feedback is resumed in Table 5 (data reports to last four years, for a total of 480 responses).

Table 5: Farewell Question—Favourite Assessment Type

This confirmed students’ preference for automated tests assessment type. Although we do not have profound answers for these preference (for instance, one could argue that a manual assessment of their answers should be more accurate and fair than an automated assessment) the informal feedback we have from students indicates that the instantaneous grade which automated tests give is probably the main reason for these preference when compared with a manually assessed written examination.

6. Final Remarks and Future Work

We find weekly assessment one of the most effective ways of leading students by the success path in the realm of introductory computer programming disciplines.

With a substantial number of students and a reduced number of teachers the only way to get it done demands automated assessment help.

Surprisingly, what we initially thought to be the lesser of two evils turned out to be perceived by students as an additional benefit (cf. Table 4 discussion).

The frequency of assessment that we advocate in introductory computing disciplines is the nodal factor of our approach to computer programming learning. Some of the benefits we found with the application of this teaching methodology where addressed in this paper and may be synthesized as following. First, it creates a methodical study rhythm among students which puts in centre stage the need for practice in know-how-to-do-it disciplines such as computer programming. Second, it allows the students to explicitly acknowledge that they are not able to solve a programming problem fast enough and by themselves. Third, it creates the opportunity for the students, assisted by the teacher, to critically analyse their study methodology and to adjust it in a timeframe that maximizes the probability of recovery. Fourth, it assists in the building of students’ computer programming knowledge from their own experience, consolidating knowledge when the assessment is positive and launching the student in a knowledge reconstruction process when the assessment is negative.

All the experiments reported in this document have been supported by the multi-paradigm programming language that brings additional positive synergies to the whole process, not discussed in this paper. Next steps include instantiating the application of the method to more classic paradigms using C, Java and other imperative languages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Miss Sónia Valente, secretary of the Information Systems and Technology Systems undergraduate program board for her kind support in obtaining some extra data about program past editions.

This work is financed with FEDER funds by the Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade—COMPETE and by Fundos Nacionais via FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia for the project: FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-022674.

References

Becker, D. A. and M. Devine (2007). Automated assessments and student learning. International Journal of Learning Technology 3, 5–17.

Ben-Ari, M. (1998). Constructivism in computer science education. SIGCSE Bulletin 30, 257–261.

Cook, W. R. (2008). High-level problems in teaching undergraduate programming languages. SIGPLAN Notices 43, 55–58.

Costello, F. J. (2007). Web-based electronic annotation and rapid feedback for computer science programming exercises. In O’neill, G., S. Huntley-Moore and P. Race (Eds.), Case Studies of Good Practices in Assessment of Student Learning in Higher Education. Dublin.

Duke, R., E. Salzman, J. Burmeister,J. Poon and L. Murray (2000). Teaching programming to beginners—Choosing the language is just the first step. Proceedings of the Australasian conference on computing education. Melbourne(Australia).

Gabriel, R. P. (1989). Draft report on requirements for a common prototyping system. Sigplan Notices 24, 93–165.

Gomes, A. and A. J. Mendes (2007). Learning to program—Difficulties and solutions. International Conference on Engineering Education—ICEE 2007. Coimbra (Portugal).

Grace, A. and T. Butler (2005). Learning management systems: A new beginning in the management of learning and knowledge. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning 1, 12–24.

Hadjerrouit, S. (2005). Constructivism as guiding philosophy for software engineering education. SIGCSE Bulletin 37, 45–49.

Jenkins, T. (2002). On the difficulty of learning to program. 3rd Annual Conference of LTSN-ICS.

Kolb, D. and R. Fry (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. In Cooper, C. (Ed.), Theories of Group Process. London: John Wiley.

Lahtinen, E., K. Ala-Mutka and H.-M. Järvinen (2005). A study of the difficulties of novice programmers. Proceedings of the 10th annual SIGCSE Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education. Caparica (Portugal).

Lister, R. and J. Leaney (2003). Introductory programming, criterion-referencing, and Bloom. Proceedings of the 34th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education. Reno, NV (USA).

Lui, A. K., R. Kwan, M. Poon and Y. H. Y. Cheung (2004). Saving weak programming students: Applying constructivism in a first programming course. SIGCSE Bulletin 36, 72–76.

Lytras, M. D. and M. A. Sicilia (2005). The knowledge society: A manifesto for knowledge and learning. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning 1, 1–11.

Milne, I. and G. Rowe (2002). Difficulties in learning and teaching programming—views of students and tutors. Education and Information Technologies 7, 55–66.

Ranjeeth, S. and R. Naidoo (2007). An investigation into the relationship between the level of cognitive maturity and the types of errors made by students in a computer programming course. College Teaching Methods and Styles Journal 3, 31–40.

Robins, A., J. Rountree and N. Rountree (2003). Learning and teaching programming: A review and discussion. Computer Science Education 13, 137–172.

Spohrer, J. C. and E. Soloway (1986). Novice mistakes: Are the folk wisdoms correct? Communications of the ACM 29, 624–632.

Steffe, L. P. and J. Gale (Eds.) (1995). Constructivism in Education. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Teague, D. and P. Roe. (2008). Collaborative learning: Towards a solution for novice programmers. Proceedings of the Tenth Conference on Australasian Computing Education. Wollongong, NSW (Australia).

Winslow, L. E. (1996). Programming pedagogy—A psychological overview. SIGCSE Bulletin 28, 17–22.

Wulf, T. (2005). Constructivist approaches for teaching computer programming. Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Information Technology Education. Newark, NJ (USA).