Original source publication: Brito, M. A. and F. de Sá-Soares (2010). Computer Programming: Fail Fast to Learn Sooner. In Lytras, M. D., P. O. De Pablos, D. Avison, J. Sipior, Q. Jin, W. Leal, L. Uden, M. Thomas, S. Cervai and D. Horner (Eds.), Proceedings of the First International Conference TECH-EDUCATION 2010—Technology Enhanced Learning: Quality of Teaching and Educational Reform, 223–229. Athens (Greece). Communications in Computer and Information Science 73. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN: 978-3-642-13165-3.

The final publication is available here.

Computer Programming: Fail Fast to Learn Sooner

University of Minho, Department of Information Systems, Guimarães, Portugal

Abstract

Computer programming is not only to know about the languages or the processes, it is essentially to know how to do it. This involves a constructivist approach in learning. For a newbie in computer programming it is hard to understand the difference between know-about disciplines and the know-howto-do-it ones. This leads to failure because when they understand they aren’t able to solve a programming problem it is usually too late to catch all the time meanwhile lost. Our solution is to get them to fail soon enough. This way they still have time to recover from an eventually bad start.

For an average student to realize a failure it is required a failed examination. This is the fourth year we are adopting automated weekly tests for fast failure and consequent motivation for study, in the university first year discipline of computer programming fundamentals. The results are convincing.

Keywords: Programming Education; Learning and Teaching Computer Programming to Novice Students; Constructivism

1. Reasons for Failure

The literature identifies several reasons for students failure when learning to program [Robins et al. 2003], some address the curriculum, others focus on methodologies [Cook 2008], resources or the best first programming language to use [Duke et al. 2000]. The inherent difficulty of programming [Teague and Roe 2008; Winslow 1996] and controlling what kind of mistakes students are more likely to make [Spohrer and Soloway 1986] are also addressed.

However, a well known truth about teaching programming is that a motivated student needs little guidance so he will succeed no matter how bad are the overall conditions, teachers included; also a student not motivated to spend some weekly hours practicing will fail no matter what the teacher says or how well the teacher explains all about computer programming.

Another conclusion our teaching experience lead to is that many students do not have a realistic idea about their effective study performance.

Some think that understanding the solutions presented by the teacher or book is enough. They will probably try to solve their first problem during the assessment itself.

Others go a little further and do some exercises but stop training as soon as they reach a solution for a certain kind of problem. However, being able to solve a ten-minute problem in a couple of hours is far from sufficient and probably the student is not even sure how the solution works.

A more insidious kind of problem emerges with students that always study in a (same) group. Frequently, what happens is that although everyone follows and contributes to the solution, it is always the same student that performs the first step from the problem statement. The others just follow the lead and genuinely believe they can alone solve the problem from the very beginning.

Papers about difficulties in computer programming learning can be found in the literature [Jenkins 2002]. In [Gomes and Mendes 2007], these difficulties are divided in categories. In this paper the main concern is to address the need to persuade students to critically analyse their study methodology and progress over the semester. So the focus is on failure reasons that can be overlapped by tuning computer programming ethodology of study.

2. Constructivism in Education

Constructivism is a learning theory in which Jean Piaget argues that people (and children in particular) build their knowledge from their own experience rather than on some kind of information transmission.

Later, based on Piaget and others’ work with the experiential learning paradigm, important works have been developed, such as Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model [Kolb and Fry 1975], which reinforces the role of personal experiment in learning and systematizes iterations of reflection, conceptualization, testing and back again to new experiences. A rich set of works about constructivism in education can be found in [Steffe and Gale 1995].

Meanwhile the discussion was brought to the computer science education field claiming that real understanding demands active learning on a lab environment with teacher’s guidance for ensuring reflection on the experience obtained from problem solving exercises. Passive computer programming learning will likely be condemned to failure [Ben-Ari 1998; Hadjerrouit 2005; Wulf 2005]. Indeed, constructivism can even be used to explain the problem of weak students and be part of the solution [Lui et al. 2004].

3. Why Weekly Assessment

An interesting study that crosses students’ individual cognitive level with the types of errors made [Ranjeeth and Naidoo 2007] suggests the need to adopt innovative strategies in order to counter the seemingly perpetual rate of failure and at the same time increase the intensity for students with better cognitive level.

Whatever the reason, the ultimate truth is that a lot of things can go wrong when learning computer programming, especially in undergraduate courses.

So it is virtually impossible to prevent them all, mainly because students tend to overestimate their own understanding [Lahtinen et al. 2005] and usually they are not very open to follow your good advices, especially if following those advices means more work.

This leads to the only winning strategy we have found so far: fail fast to learn sooner. If frequent assessment opportunities are given to the student, no matter the reason why he is eventually performing badly, two important goals are immediately achieved:

there is still time to change student’s study methodology and

the teacher finally gets some real attention from the student to his good advices.

Even for students who do not need to fail to correct eventual study errors, we observe that weekly assessment is an extra motivation for not postponing study and consequently they will also attend next class better prepared [Becker and Devine 2007].

Other medium term issues related with tuning the discipline from year to year are also addressed by weekly assessment. The ordering of different concepts by difficulty [Milne and Rowe 2002] can be inferred from final examinations or by directly asking students and teachers, but if we have automated weekly assessments this kind of data is all over. So it is easier tuning the classes’ distribution along the year, dedicating more time and exercises to those issues we know students need more time to assimilate and eventually to concentrate easier subjects in less classes.

4. How Weekly Assessment

Weekly assessment involves several dimensions. First we need a methodology and then implementation resources. For the methodology we have a set of supposedly good advices and tutorial support during classes but in this context it is enough to focus on the method the students need to follow each week.

4.1 Our Method

Our learning methodology includes a method of weekly work composed of the following steps:

First read the book: The students should always read the main reference of the course before attending the class. This is a well known way of preparing the brain to the concepts that will be discussed in class. It is not intended or expected that the students understand everything but they will have a precious idea of the main concepts of the current week.

Participate in the class: In the subsequent class concepts will be contextualized, examples will be given and expected difficulties will be addressed. Although students need to practice to learn to program, they should leave the class with the concepts well known. They now know-about, they have an idea of how-to-do-it, they are prepared to go on and try to do it by themselves.

Try everything: Then go back to the book and class notes and believe nothing—code everything and experiment in the programming environment. Revisit everything that was read and said, always coding it. Introduce changes in the exercises and check if the outcome matches the expected result. Solve and run the associated exercises. The biggest problem is not understanding the basic concepts but rather learning to apply them [Lahtinen et al. 2005].

Use the laboratorial classes to self assessment: A special set of exercises is weekly prepared for the students to perform a self assessment. The laboratorial class is usually used for that purpose.

Assessment: Finally, the weekly assessment gives feedback to the student about the effectiveness of his work that week. This is very important for several reasons such as avoiding study relaxation, creating a timely alert to students’ ineffective study and pinpoint the parts of the syllabus that require revision by the student.

Tutorial guidance: With the feedback provided by the assessment it is crucial to discuss the success of each student so far. Computer programming is in some extension a yes or no competence. This means that grades near zero and grades near hundred per cent are usually normal. So in the first weeks, grades bellow 80% should be carefully analysed—what happened that justifies that the student did not reach 100%? Not enough study? Not enough experimental practice? Should he study not more but better? The role of the laboratorial teacher is crucial at this point. There are different students’ capabilities and the teacher must have answers to all of them even if they are spread by different levels of Bloom’s taxonomy [Lister and Leaney 2003]. He must diagnose and address the personal difficulties of each student giving him guidance and self confidence.

Besides the already mentioned advantages from each step of the method, the whole set addresses main constructivism claims since provides systematic progressive interactions with the same concepts with teacher’s guidance and consequently facilitating students’ reflection and apprehension.

4.2 Self Assessment

Students have a weekly project composed of exercises similar to the ones in the weekly assessment. Once their weekly study is done, and only then, they try to solve all the questions in order to self assess their knowledge. In case of difficulties they should go back to the book or ask teacher for guidance.

The resolution of the project is submitted to teachers for control purposes.

4.3 The Weekly Assessment

The weekly assessment is not just a weekly assessment–it is a weekly assessment with weekly feedback, i.e. the main goal is not just to put some pressure on the students. It would not be the same if the students did weekly assessment but only obtain the grades at the end. An important feature is that each student has immediate feedback and can still correct in time his study methodology.

Unfortunately it is incredibly simple for a very well intentioned student to diverge from the success path without notice.

We are dealing with novice first year undergraduate students and it is never too much to stress that we are dealing with novice first year undergraduate students... This means an extra charge of distractions aside from the inherent adaptation issues.

Completely out of that path of success is the temptation to stop studying after understanding a problem’s solution, but before knowing how to do it himself. Even if the student gets to the solution of a kind of problem he must consider the time that was necessary to do it—it is still a long way (ok, maybe not always that long) between the points I-can-solve-it and I-can-solve-it-fast-enough.

It is also not rare that students study a lot and know very little, just because they are not doing it well. For instance, a student can spend daily hours studying syntax issues, solving problems and theoretical questions without really solving any problem himself... big mistake!

Nevertheless, if by any chance an already rare student perceives or suspects of flaws in his study methodology the normal tendency will be to postpone eventual corrective measures even if he knew one and generally that is not the case.

But even worse than that is the situation of a student that has the chance to have an attentive teacher that diagnosis one of those described issues and gives the student guidance and concrete corrective measures... nevertheless the standard student will not trust the teacher’s diagnosis.

All this issues can be solved in time if you give the student the opportunity to fail fast if something is going wrong. This opportunity is called weekly assessment and is the main secret that allows the student: (i) to perceive that there is an issue to address, (ii) to believe the issue should be addressed, (iii) to believe the issue will not disappear by itself, and (iv) to address it in time.

Weekly assessment will give the student the opportunity to correct whatever may be wrong without having to wait till next (year or semester) edition of the course.

4.4 Implementation Resources

Some authors ([Costello 2007] and [Duke et al. 2000]) agree on the merits of frequent assessment but have a small enough number of students or a big enough number of hours x teachers.

We do not have such resources and have almost two hundred students and only a laboratorial teacher. Nevertheless, a third factor in the equation may be automated testing of the problems solved by students.

5. Our Outcomes with Weekly Assessment

Since we introduced weekly assessment the number of retained students was dramatically reduced.

However, this is not possible without some extra resources. In the case we choose to invest in automated assessment.

A first and strong indicator of the weekly assessment success is the evolution of the percentage of students that stay till the end, i.e. that do not drop at the middle of the semester.

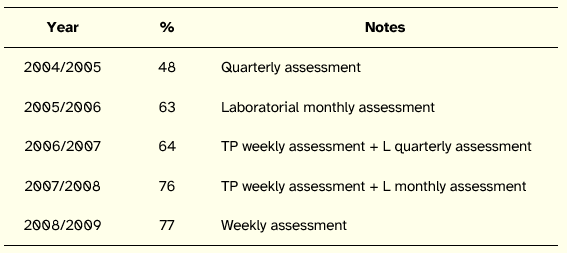

Table 1 shows this evolution for the last five years. The reading of this table is not completely linear because some other factors changed meanwhile. However, the evolution is quite clear and shows that the efforts in increasing the assessment frequency resulted in greater percentage of students that stick till the end of semester.

Table 1. Students that stick till the end of semester percentage evolution

In 2004/2005 a small project was quarterly assessed; i.e. there were two assessment points per semester.

During 2005/2006 small problems resolution in computers’ lab were added to the assessment on a monthly basis.

In 2006/2007 a weekly automated theoretical-practical (TP) assessment was implemented and complemented with a quarterly laboratorial (L) assessment.

During 2007/2008 the frequency of laboratorial assessment was increased to monthly.

Finally, 2008/2009 was the year when the whole assessment was automated and weekly performed.

The ratio of approval is also growing—4% in 2005/2006, 2% the year after, 1% in 2007/2008 and finally a huge 13% jump last year with the weekly fully automated assessment—a 20% total improvement in five years! It should be mentioned that this evolution was achieved neither by shrinking the syllabus nor by decreasing the level of rigor imposed to the course over the years.

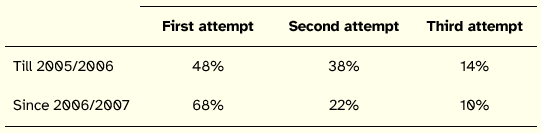

Another important indicator is the number of students being able to succeed the discipline on first attempt or better said the number of attempts a student needs in order to succeed.

For Table 2 construction we considered the division success-before and successafter weekly assessment implementation.

Table 2. Percentage of approvals in first, second and third attempts

Achieving success in first attempt is very important for several reasons. There is an associated cost for the student which is both monetary and functional. For teachers and university second attempts represent an increased complexity in resources and management.

Consequently, a twenty per cent increment in first attempt success is a very positive result.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Miss Sónia Valente, secretary of the Technologies and Information Systems undergraduate course board for her kind support in obtaining some extra data about course past editions.

References

Becker, D. A. and M. Devine (2007). Automated assessments and student learning. International Journal of Learning Technology 3, 5–17.

Ben-Ari, M. (1998). Constructivism in computer science education. SIGCSE Bulletin 30, 257–261.

Cook, W. R. (2008). High-level problems in teaching undergraduate programming languages. ACM SIGPLAN Notices 43(11), 55–58.

Costello, F. J. (2007). Web-based electronic annotation and rapid feedback for computer science programming exercises. In O’neill, G., S. Huntley-Moore and P. Race (Eds.), Case Studies of Good Practices in Assessment of Student Learning in Higher Education. Dublin.

Duke, R., E. Salzman, J. Burmeister, J. Poon and L. Murray (2000). Teaching programming to beginners—choosing the language is just the first step. Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Computing Education 2000. Melbourne (Australia).

Gomes, A. and A. J. Mendes (2007). Learning to program—Difficulties and solutions. International Conference on Engineering Education—ICEE 2007. Coimbra (Portugal).

Hadjerrouit, S. (2005). Constructivism as guiding philosophy for software engineering education. SIGCSE Bulletin 37, 45–49.

Jenkins, T. (2002). On the difficulty of learning to program. 3rd Annual Conference of LTSN-ICS.

Kolb, D. and R. Fry (1975). Toward an applied theory of experiential learning. In Cooper, C. (Ed.), Theories of Group Process. London: John Wiley.

Lahtinen, E., K. Ala-Mutka and H.-M. Järvinen (2005). A study of the difficulties of novice programmers. Proceedings of the 10th annual SIGCSE Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education. Caparica (Portugal).

Lister, R. and J. Leaney (2003). Introductory programming, criterion-referencing, and Bloom. Proceedings of the 34th SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education. Reno, NV (USA).

Lui, A. K., R. Kwan, M. Poon and Y. H. Y. Cheung (2004). Saving weak programming students: Applying constructivism in a first programming course. SIGCSE Bulletin 36, 72–76.

Milne, I. and G. Rowe (2002). Difficulties in learning and teaching programming—views of students and tutors. Education and Information Technologies 7, 55–66.

Ranjeeth, S. and R. Naidoo (2007). An investigation into the relationship between the level of cognitive maturity and the types of errors made by students in a computer programming course. College Teaching Methods and Styles Journal 3, 31–40.

Robins, A., J. Rountree and N. Rountree (2003). Learning and Teaching Programming: A Review and Discussion. Computer Science Education 13(2), 137–172.

Spohrer, J. C. and E. Soloway (1986). Novice mistakes: Are the folk wisdoms correct? Communications of the ACM 29, 624–632.

Steffe, L. P. and J. Gale (Eds.) (1995). Constructivism in Education. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Teague, D. and P. Roe (2008). Collaborative learning: towards a solution for novice programmers. Proceedings of the Tenth conference on Australasian Computing Education 78. Wollongong (Australia).

Winslow, L. E. (1996). Programming pedagogy—A psychological overview. SIGCSE Bulletin 28, 17–22.

Wulf, T. (2005). Constructivist approaches for teaching computer programming. Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Information Technology Education. Newark, NJ (USA).